CHAPTER 15 Eyes and Adnexa

Cytologic examination of the eye and surrounding structures is frequently helpful in determining general categories of pathology before performing more invasive or expensive procedures. The following cytodiagnostic categories apply to the various anatomic sites of the eye. It should be noted that more than one presentation might occur in a specimen at a time.

Cytologic Biopsy Considerations

Aspiration of focal and diffuse lesions is recommended for the lesions of the eyelid, eye, and other associated structures. The thinner conjunctival tissue requires scraping with a blunt instrument such as an ophthalmic spatula or soft brush. The use of a brush was shown to reduce cellular clumping of samples and provide less cellular distortion (Willis et al., 1997). Exudate material, duct washings, and aspirate material can be used as specimens of the nasolacrimal apparatus.

EYELIDS

Normal Histology and Cytology

The dorsal and ventral eyelids are thin extensions of facial skin that meet at the lateral and medial margins, called canthi. Two to four rows of lashes are found on the upper eyelid at the free margin of the dog, while the cat has a row of cilia (Samuelson, 1999). The outermost layer resembles typical skin, with keratinized squamous epithelium and numerous hair follicles that lie in close association with sebaceous and modified sweat glands. Striated muscle fibers course through the deeper layers. The innermost layer, the palpebral conjunctiva, is lined by pseudostratified columnar epithelium containing numerous goblet cells. Near the margins of both eyelids at the posterior end are the meibomian or tarsal glands. These large sebaceous glands lie adjacent to the palpebral conjunctiva and contribute to the lipid component of the tear film.

Neoplasia

Diffuse neoplasms of the eyelids involve squamous cell carcinoma (especially in cats), sarcoma, mast cell tumor, and lymphoma. Focal presentations involve sebaceous gland adenoma/adenocarcinoma (canine), papilloma (canine), mast cell tumor (feline), melanoma (canine), squamous cell carcinoma (feline), cutaneous basilar epithelial neoplasm (feline), and histiocytoma (canine). Benign tumors predominate but occasionally malignant tumors such as apocrine sweat gland tumors can invade the globe and extensively damage the eye (Hirai et al., 1997).

Cyst

Chalazion, or meibomian cyst, refers to the granuloma formed from the irritating effects of ruptured sebaceous secretions or blockages caused by tumors. The leakage of meibomian cyst material incites an inflammatory response similar to a foreign body reaction. In this situation, numerous foamy macrophages, few giant cells, neutrophils, lymphocytes, amorphous debris, and sebaceous epithelium are present.

CONJUNCTIVAE

Normal Histology and Cytology

The palpebral conjunctiva is lined by a pseudostratified columnar epithelium containing goblet cells. Goblet cells appear as distended cells with an eccentric nucleus. The cytoplasm may contain clear vacuoles or red-blue granules. Mucus is common on cytologic specimens, appearing as lightly basophilic amorphous strands. The palpebral conjunctiva is continuous with the bulbar conjunctiva, which reflects onto the globe and joins the corneal epithelium. The junction of the two conjunctivae creates a sac termed the fornix. This blind sac is lined by stratified cuboidal epithelium containing many goblet cells. The bulbar conjunctiva consists of sheets of stratified nonkeratinized squamous epithelium, mostly intermediate and superficial with less than 1% goblet cells as detected by impression cytology (Bolzan et al., 2005). There are no significant numbers of inflammatory cells; however, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue is located below the squamous layer of the palpebral conjunctiva near the fornix, where goblet cells are absent.

Hyperplasia

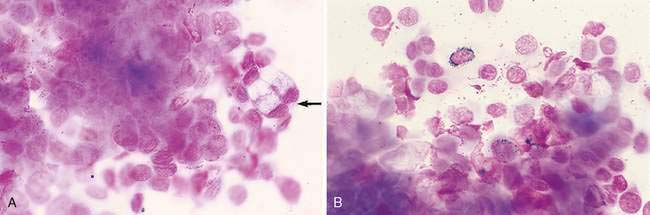

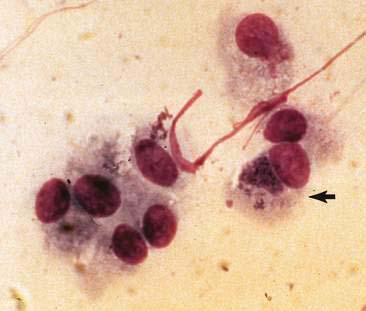

Conditions such as keratoconjunctivitis sicca, vitamin A deficiency, chronic disease, and trauma from mechanical irritants result in increased cell numbers, sometimes with evidence of metaplasia. These specimens contain many keratinized epithelial cells and goblet cells (Fig. 15-1A) (Murphy, 1988). Increased pigmentation of the epithelium may also occur such that the cytoplasm contains numerous fine, black-green melanin granules (Fig. 15-1B).

Inflammation

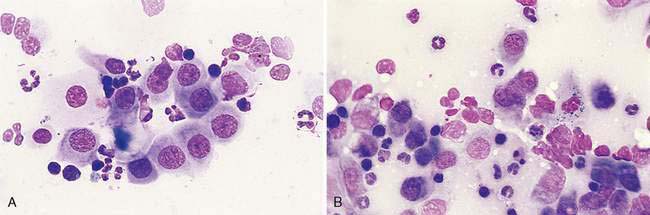

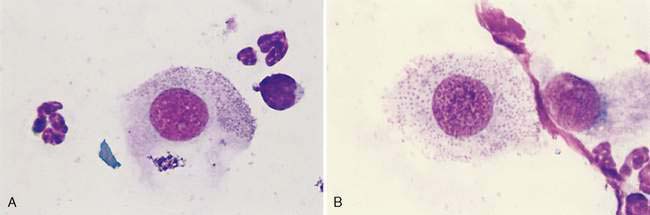

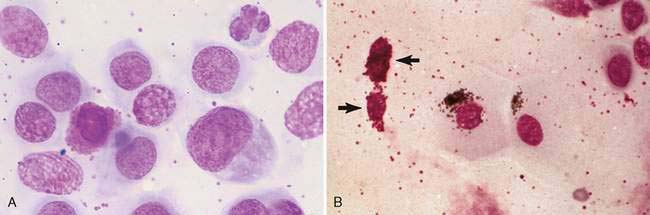

The predominant cell type present characterizes the conjunctivitis. Neutrophilic conjunctivitis may be associated with infectious agents such as bacteria and viruses as well as noninfectious causes. One should suspect a bacterial origin if degenerative changes are present. With viruses such as feline herpesvirus and chronic canine distemper virus, nondegenerate neutrophils predominate (Fig. 15-2A). Multinucleated epithelial cells (Fig. 15-2B) were found in approximately half of the cases with feline herpesvirus (FHV-1) infection diagnosed by culture or immunofluorescent assay (Naisse et al., 1993). Eosinophils have been associated with FHV-1 infection (Fig. 15-3A&B) (Volopich et al., 2005). Intranuclear inclusions in FHV-1 infection are occasionally encountered in conjunctival smears (Volopich et al., 2005) but are more readily seen in histologic sections. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test has greater sensitivity for detection of the virus than other tests (Stiles et al., 1997). Canine distemper inclusions appear pink with alcohol-based Romanowsky stains but purple with aqueous-based Wright stains.

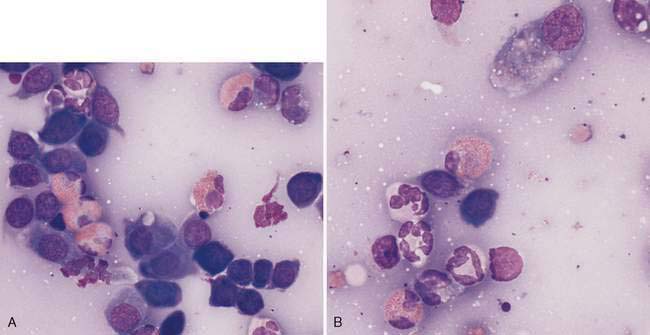

Other infectious causes include feline chlamydiosis, which presents as variably sized discrete basophilic to bright magenta bodies in the cytoplasm of epithelium within first 2 weeks of infection. Small elementary bodies (0.3 μm) are shed that infect new cells and grow into larger (0.5 to 1.5 μm) initial bodies (Greene, 1998). The initial bodies (Fig. 15-4A&B) proliferate to become a large, membrane-bound reticulate body containing many elementary bodies (Fig. 15-5). In the Naisse et al. study (1993), visible epithelial inclusions were present in only a third of the cases positively identified by immunofluorescent assay as Chlamydia psittaci, currently called Chlamydophila felis. Besides fluorescent antibody detection, cell inoculation, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), PCR procedures, or immunochemistry may be used (Volopich et al., 2005; von Bomhard et al., 2003). In one case reported, chlamydial infection in a cat was possibly transmitted from a macaw (Lipman et al., 1994). In another study, of 226 conjunctival samples, 39% were positive for non–C. felis chlamydial DNA, identified as Neochlamydia hartmannellae, in cytologic samples with eosinophilic inflammation (von Bomhard et al., 2003). Infection with feline Mycoplasma sp. presents as small basophilic granules similar to the elementary bodies of chlamydial infections with the exception that they are adherent to the surface membrane (Fig. 15-6A&B). One study from Belgium indicated mycoplasmal infection had an incidence of 25% in cats with conjunctivitis (Haesebrouck et al., 1991).

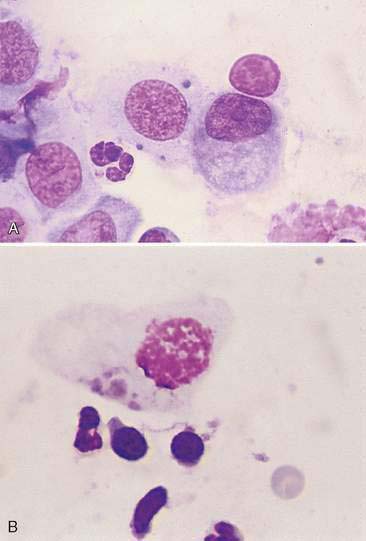

Noninfectious causes include keratoconjunctivitis sicca and allergic conditions. Eosinophilic conjunctivitis has been associated with a hypersensitivity reaction in the cat. In this situation eosinophils are seen commonly (Fig. 15-7A). Mast cell infiltrates may also be so numerous that there is concern for a conjunctival mast cell tumor (Fig. 15-7B). Lymphocytes and plasma cells have been associated with allergic conditions as well as with early canine distemper infection or with chronic inflammation of the conjunctiva.

Neoplasia

Epithelium is frequently atypical and hyperplastic as a result of severe inflammation; therefore, neoplasia may be difficult to diagnose confidently. Neoplasms found associated with the conjunctival area include squamous cell carcinoma, papilloma, melanoma, lymphoma, hemangiosarcoma, and mast cell tumor. An uncommon location of transmissible venereal tumor has been the conjunctivae of the upper and lower eyelids (Boscos et al., 1998).

NICTITATING MEMBRANE

Normal Histology and Cytology

The third eyelid, or nictitating membrane, is a large fold of conjunctiva protruding from the medial canthus. It contains a T-shaped cartilaginous plate surrounded by glandular epithelium that is serous in the cat and seromucoid in the dog (Samuelson, 1999). The palpebral and bulbar surfaces are covered by nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium. The free margin of the membrane is pigmented and, cytologically, fine green-black melanin granules can be found within the epithelium. Numerous variably sized lymphoid aggregates with overlying epithelium having microvilli or microfolds (M cells) on the apical surface are associated with the bulbar surface of the nictitating membrane (Giuliano et al., 2002). The stroma also contains fibrous connective tissue.

Inflammation

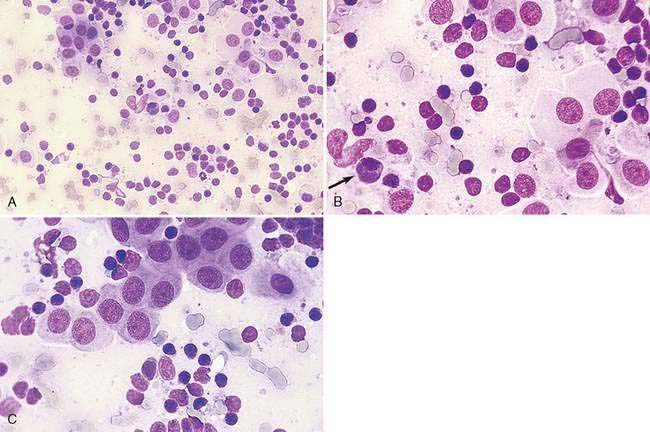

With follicular conjunctivitis there is a mixed population of lymphoid cells that resembles a hyperplastic lymph node (Fig. 15-8A&C). Plasma cell infiltrates (plasmacytic conjunctivitis or plasmoma) have been seen in German Shepherd dogs. These thickened depigmentating lesions are composed of numerous well-differentiated plasma cells.

Neoplasia

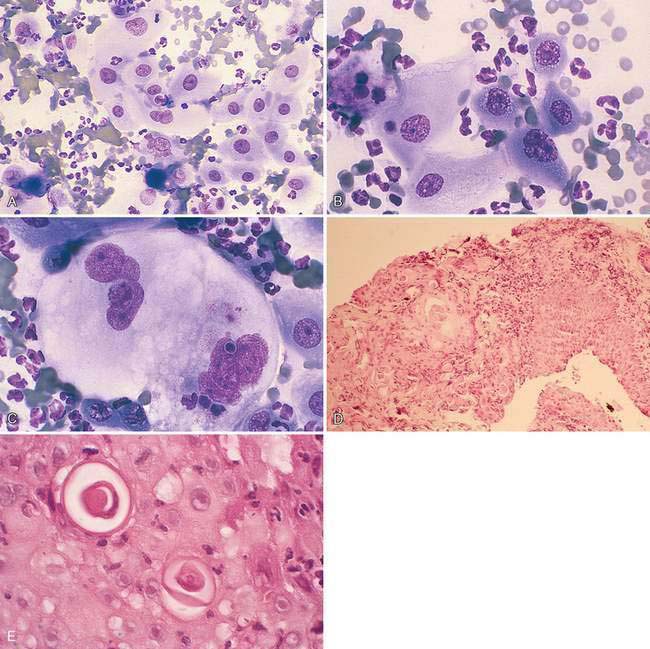

These are similar to those seen in the conjunctivae. Adenocarcinomas, papillomas, and malignant melanomas are most common in dogs. A report of an adenocarcinoma affecting the gland of the nictitating membrane in a cat demonstrated the presence of malignant epithelial cells from impression smears of excisional biopsy material (Komaromy et al., 1997). Squamous cell carcinoma, when present on the nictitating membrane, is considered an extension from the eyelid. It appears similar to those found in the skin often with nonseptic purulent inflammation (Fig. 15-9A-E). Dogs and cats most commonly present with hemangiosarcoma and hemangioma within the nonpigmented epithelium of the nictitating membrane compared with the conjunctivae. Exposure to ultraviolet light is suspected to be a risk factor for these endothelial neoplasms (Pirie et al., 2006; Pirie and Dubielzig, 2006).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree