Chapter 20

Exhibiting Amphibians

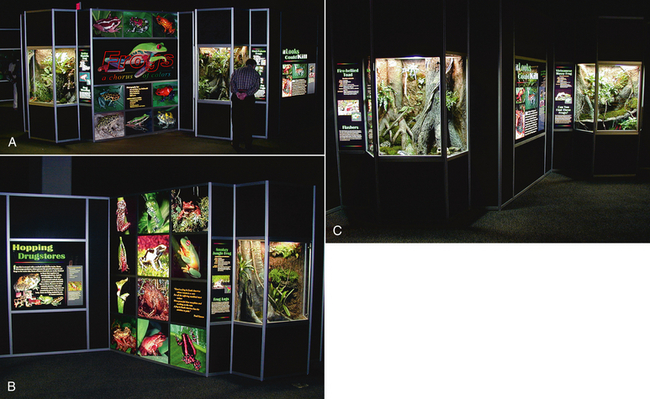

In 2001, Peeling Productions, the exhibit arm of Clyde Peeling’s Reptiland, a zoologic park in Allenwood, Pennsylvania accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA), began planning a large-scale traveling exhibition called Frogs—A Chorus of Colors. Having exhibited amphibians on a small scale at our permanent facility in Pennsylvania, we knew that a big, complex project would require forethought. We began by visiting public and private amphibian facilities to learn from the experiences of others. Our goal was to emulate the successful aspects of existing exhibits and improve on their weaknesses. Over the next 2 years our exhibit team designed, prototyped, and fabricated the exhibition at our production facility in Pennsylvania, learning along the way. The finished exhibition premiered in 2003 and has been on a nationwide tour of museums, zoos, and science centers ever since (Figure 20-1). Building Frogs—A Chorus of Colors affected the trajectory and interests of our company. We created a second copy of the exhibition in 2005 and have since built a series of custom amphibian exhibits for other clients. Each of these projects has left us with strong opinions about what works and what does not. While this chapter is primarily about creating public exhibits, the principles can be applied to amphibian displays of any kind.

FIGURE 20-1 A-C, Frogs—A Chorus of Colors is a large traveling exhibition that began a tour of museums, zoos, and science centers in 2003. The exhibition has been hosted by prestigious institutions throughout the United States and Canada. Exhibited well, frogs have an enduring charisma in public exhibits.

What to Avoid

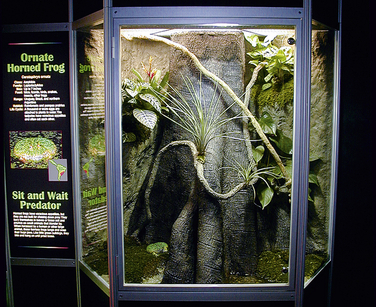

The most common mistake in public amphibian exhibits is over planting. It is tempting to create a beautiful, lush habitat that closely mimics an animal’s native environment and call it an exhibit, but planting with abandon ensures that the subjects of the exhibit—the amphibians—will rarely be seen. Nothing frustrates visitors more than an animal exhibit without animals, even if it is a stunning botanical display. Of course, the solution to overplanting is not to eliminate the plants; there is no reason to sacrifice aesthetics or naturalism. However, planting, arranging props, and all other aspects of decorating an exhibit must be done strategically to keep the animals in view (Figure 20-2).

FIGURE 20-2 Keeping exhibit animals visible is a paradigm of good exhibit design. Plants and other décor should be arranged strategically.

One Approach to Exhibit Design

Species Selection

The natural starting point for designing an amphibian exhibit is species selection, and the range of possible species is often dictated by the overarching message or theme of the project. Whatever the theme is, choosing a species that will engage visitors should be a priority. Otherwise, why bother with an exhibit? Defining the qualities of a good exhibit species is subjective, but a few basic questions are worth asking. Is the species nocturnal or diurnal? Does it perch in the open or prefer to stay hidden? Is it colorful or unusual enough to catch a layperson’s eye? Is there an interesting or important story to tell? How large is it? Can multiple specimens be kept together? Has anyone else exhibited it successfully?

One of the hidden costs of exhibiting amphibians is maintaining a backup colony. Most species are sensitive to subtle environmental changes and can decline quickly if something goes wrong. In addition, the potential for introduced epidemic diseases like chytridiomycosis and ranavirus can quickly ravage a colony or an entire collection. Sooner or later, some specimens will probably need to be removed from exhibit because of illness, social stress, or death. It can be difficult to find replacements in a pinch because many species are only available seasonally. Furthermore, adult specimens of many species come at a premium, if breeders are willing to give them up at all. The obvious solution is to raise backups. Exhibiting amphibians requires allocating space, staff, and budget to continually maintain at least as many animals off display as needed on exhibit. We maintain 400 amphibian specimens off exhibit at Reptiland to support approximately 200 display animals in our various exhibitions (Figure 20-3). Of course, quarantine of newly acquired specimens takes even more space and time.

Enclosures

One of the most important considerations in enclosure design is keeper access. It is tempting to think that tall enclosures can be serviced from above or that keepers can reach through small openings to provide care. The reality is that tanks that are difficult to enter will not be cared for as well as those that have easy access. Make doors large enough to allow an adult person to lean inside and locate doors so that shorter people can reach all corners of the enclosure. Consider how difficult it will be to reach around branches and other obstructions to clean glass or tend plants. If possible, include front access to enclosures, so keepers can see the exhibit from a visitor’s perspective while cleaning—working in reverse is far more difficult (Figure 20-4). All doors should be designed to avoid accidentally squashing an amphibian when closing, and perimeter gaps should be small enough to limit insect escapes.

FIGURE 20-4 Front access doors allow keepers to see an exhibit from the public’s perspective while cleaning.

Interior Landscapes

Interior decor puts exhibit animals in context and provides a visual backdrop. Its complexity depends on the project’s scope and budget. Low cost scenes can be constructed with the use of real rocks, substrates, and branches. Completely “naturalistic” scenes, cast in concrete or resins, are much more costly but provide the illusion of a “slice of nature” (Figure 20-5). Well-designed fabricated interiors are also lower maintenance and can include hidden infrastructure such as contained planting pockets, plumbing, and conduit for electric cables.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree