Brian H. Anderson, Andrea Ritmeester, Brendon Bell and Andris J. Kaneps • Aim and philosophy of the prepurchase examination. • General approach and examination procedure. • Special considerations and ancillary tests. A rigorous and thorough examination of the athletic horse by a veterinarian who understands and is familiar with the sporting endeavors of a particular athlete is a challenging and potentially troublesome task. With practice and diligence it can be a very rewarding professional and financial experience. In order to conduct such examinations proficiently, knowledge of the types of injuries and diseases affecting athletic horses and which may shorten or cause problems in a career should be understood. In this chapter the aim and philosophy of the prepurchase examination, general approach and examination procedure used, the use of special examination techniques and the differences in examination approach between various athletes will be discussed. The prepurchase examination of horses intended for breeding will not be discussed but has been reviewed elsewhere.1,2 The aim of the examination of the equine athlete prior to purchase is to first identify, and second assess, the relative significance of factors of a veterinary nature, which at the time of examination might impair athletic performance in the occupation for which the horse is intended.3 In addition, conditions that have the potential for impairment of athletic performance in the future should also be identified and an opinion of their significance made in light of the horse’s intended use.3,5 The way in which the opinion of the examining veterinarian is presented to the purchaser has become very controversial. Unfortunately, it is a frequent perception by the purchaser that a veterinarian’s examination prior to purchase provides a warranty that the prospective animal is free of all impediments currently and in the future and that such an examination in some way guarantees a risk-free purchase. This perception has been perpetuated to some extent by the use of the terms ‘sound’, ‘suitable’ or ‘serviceable, all of which when used in the context of a prepurchase examination imply a degree of warranty. Using these terms when giving an opinion may leave the examining veterinarian legally vulnerable if the horse should prove to be unusable by the purchaser and they are not recommended.6 Another reason why it is unwise to use such terminology is that in many instances a complete examination of the horse to be purchased is not possible. Providing an opinion on suitability or serviceability based on an incomplete examination is fraught with difficulties. The veterinarian should confine his or her opinion to the functional significance of relevant examination findings.7 A decision to purchase the horse or a decision on the suitability or serviceability of a horse for a specific intended purpose is a business judgment that is the sole responsibility of the purchaser and is made on the basis of a variety of factors, only one of which is the report provided by the examining veterinarian.6,7 It is common to find some clinical problems in athletic horses. Rather than take the easy road of advising against purchase where problems are recognized it is better to provide the purchaser with a balanced assessment of risk. Probably the most practical method is to assign a measure of likelihood or percentage chance that an abnormality or clinical finding will impair athletic performance.4,8 In forming such an opinion the veterinarian draws on her or his own experience, the experience of others and the scientific literature. For example, recent evidence suggests that the presence of dorsal medial intercarpal disease identified on presale radiographs of the carpus of Thoroughbred yearlings is associated with a 20% chance of an affected horse not starting a race.9 It should be noted that the way in which the veterinary opinion is presented to the purchaser differs around the world. The variation often reflects the results of court decisions in cases of dispute and the establishment of legal precedent.6 For example, the British Equine Veterinary Association recommends that the opinion given on examination for purchase be that a horse is ‘suitable or unsuitable’ for the purpose for which it is intended.3 The equine industry accepts this method and the British legal system recognizes it as reasonable.10 In order to perform a successful prepurchase examination, a number of requirements should be met and include the following:10 • Clear communication with the purchaser or purchaser’s agent, vendor or vendor’s agent before, during and after the examination. This communication should be both verbal and in writing. The limitations of the veterinary examination should be discussed with the purchaser together with an explanation of how the examination findings will be reported. The results of the examination are privileged and confidential and are the property of the purchaser. • If the vendor is a client of the veterinarian (current or past) this represents a potential conflict of interest. All parties should be consulted and if the examination is to go ahead this agreement should be made in writing (see Appendix at the end of this chapter). Part of this agreement should include full disclosure of relevant medical information by the vendor relating to the horse to be examined. It is strongly recommended not to proceed with the examination if the vendor refuses to provide this information to the purchaser or purchaser’s agent (see Appendix). • Written confirmation of what portions of the examination the purchaser requires (see Buyer’s statement in Appendix at the end of this chapter). The requirement of additional ancillary tests should be indicated. Where regular examination procedures are unable to be performed (e.g. horse is not broken to lead) this should be detailed in the written report furnished to the purchaser. Other than for young stock, the horse should be in full athletic work and it is unwise to perform examinations on animals not in regular work because previous lameness or back problems may not be apparent.8 These issues should be discussed carefully with the purchaser or purchaser’s agent. • A vendor’s statement (see Appendix) should be completed in writing prior to examination of the horse. • It is ideal although often not possible to have the vendor and purchaser present during the examination. A methodical and thorough examination process is required which includes examination before and after strenuous activity, preferably similar to that performed by the horse in its chosen occupation. Adequate personnel and conditions throughout this procedure are necessary. • A thorough knowledge of the intended use of the horse. • Precise and detailed recording of examination findings. • Be able to advise on the necessity of ancillary diagnostics and perform these or refer on for specialist examination. • If the horse is to be insured or is being purchased for resale these issues should be discussed thoroughly with the purchaser. While some conditions identified during the examination will be acceptable risks for a certain intended use they may cause problems if the horse is to be insured or resold. For example, a distal intermediate ridge osteochondral fragment of the hock not resulting in clinical signs may be a low risk for purchase in a Thoroughbred yearling that is to be trained and raced by the buyer. If the purchaser, however, intends to condition the horse and sell it in a ‘two year old in training sale’ such a radiographic finding might deter a future purchaser. In addition, an insurance exclusion could be put in place on such a horse if the purchaser opted to surgically remove this fragment prior to further sale. Veterinarians use a variety of protocols for examination of the athletic horse prior to purchase.6–8,11,12 Some veterinary societies recommend a standardized procedure that should be used by their members.7,8,11,13 By following such methods a degree of protection is afforded the veterinarian in case of litigation and a standard method reduces the chances of missing problems. However, other veterinary associations such as the American Association of Equine Practitioners have not produced an official step-by-step protocol because of the legal ramifications that may arise if a veterinarian did not strictly adhere to the policy. In addition, by not using a standard protocol, veterinarians are free to adopt their own methods of examination. One method used by the authors,7 and one that has been well accepted in Australia, New Zealand and Great Britain, is based on a five-stage procedure and this is described below. An accurate description of the horse is required. A vendor’s/owner’s statement should be completed (see Appendix). The current state of work should be noted and the resting examination conducted. This part of the examination is usually performed within the horse’s stall or stable, the horse having been at rest for at least 30 min. Access to a dark area is useful for examination of the eyes. A nose to tail examination should be conducted and the hands passed over every part of the body. Each foot should be picked up, examined and a hoof tester applied. The limb joints are checked for effusion and flexed to detect pain or limitation of movement. The palmar/plantar flexor tendons, ligaments and soft tissues are evaluated for swelling, heat and pain. The accompanying checklist (see Appendix) should be followed precisely so that no part is overlooked. With experience the veterinarian develops an automatic inspection procedure. The horse is then brought out of the stable and inspected thoroughly from all sides. Conformation is evaluated with the horse standing on a level surface. At this stage if any obvious defect is present which would impair the function of the animal the examination is stopped with the consent of the purchaser. The premature termination of the examination and the reason is explained in the report. A competent attendant should handle the horse. The horse is walked 20 m away from the examiner and then back. The horse should be viewed from the front, back and sides. The horse is then trotted for 30–40 m and trotted back and then trotted in a circle both ways. The horse should be turned one way and then the other in tight circles and then backed a few paces. Coordination and proprioception are carefully assessed and to test for hindlimb strength a ‘tail pull test’ is used. Following this, a full series of flexion tests as outlined in the guidelines are performed. The significance and interpretation of flexion tests are controversial.14 Force applied, duration of application, age and work history can all influence the outcome of these manipulations. Flexion tests should not be interpreted in isolation. Positive flexion tests without concurrent lameness or other clinical abnormalities may have little clinical significance.15 In our hands flexion tests have proved useful as an indicator or ‘warning’ that further investigation may be required. More emphasis is placed on a positive response to flexion if a change in gait is maintained for more than 2–3 strides.14 • induce rapid deep breathing so that unusual breathing sounds can be heard • tire the animal so that strains and injuries and other exercise-related problems (e.g. epistaxis) may be revealed after a period of rest • increase the action of the heart so that exercise-related cardiac abnormalities may be detected, e.g. atrial fibrillation.7 Examination of claims made against veterinary surgeons relating to the prepurchase examination show they are of two broad types.16 In the first instance, the veterinarian is accused of not detecting an abnormality that subsequently becomes a problem. This most commonly relates to lameness occurring soon after purchase. A careful and thorough examination procedure should help reduce the chances of inadvertently making such errors. Testing for drug administration may also act as a deterrent to the use of agents that may hide lameness problems or help confirm the presence of such agents at the time of examination. Notwithstanding this, it behooves the examining veterinarian to confine his/her opinion to fact, which is supported by experience and knowledge of the scientific literature. A second opinion from a respected colleague may be very useful. Because opinions between veterinarians differ, it is best to confine any opinion given in terms of the degree of risk that any defect or abnormality may have currently or in the future on athletic performance. It is recommended that the veterinarian does not express his or her opinions relating to the outcome of the examination procedure to the vendor, although some veterinarian’s believe otherwise.17 The assessment of conformation is a very important part of the prepurchase examination. Many veterinarians believe that conformation, or more specifically, deficiencies in conformation, play a significant role in the maintenance of athletic soundness and contribute to the ability of elite performers. For example, it is well known that some conformational faults predispose athletic horses to injuries and lameness.18–22 In addition, many astute observers of horses believe that the way horses are ‘put together’ has a major effect on how successful they are in various disciplines.19,22 Unfortunately, objective scientific data to support these commonly held opinions is limited. Moreover, very talented individuals appear to compensate for deficiencies in conformation. It is probably true to say, however, that marked discrepancies from what is considered optimal conformation result in injuries that limit athletic performance. Limitations in the short term, especially in gifted individuals, can be overcome, but in the long term recurrent injury and lameness is more likely. Issues relating to the conformation assessment of various athletic horses are discussed below under the examination of each athlete. The reader is directed to more extensive recent reviews on the subject.18–23 Although a variety of laboratory evaluations may be useful as ancillary aids during the prepurchase examination,24,25 drug testing and those tests required for insurance purposes or certification of disease status when horses are transported between states or countries are the most common. Blood tests such as evaluation of the hemogram, plasma fibrinogen and serum chemistry are not routinely performed but would be indicated to determine if observed clinical symptoms were significant, e.g. nasal discharge, cough, elevated rectal temperature or submandibular lymph node enlargement. The vendor’s permission should be sought and, to avoid confusion with the interpretation of results, blood should be collected prior to exercise. The simple act of collecting a blood sample at the time of examination, especially if the vendor is advised in advance, can have a deterrent effect. Storing the blood at the veterinarian’s practice to be analyzed at a later date at the discretion of the purchaser can potentially lead to problems relating to the ‘chain of custody’. Instead we recommend the immediate analysis of blood collected for drug screening. In some countries (e.g. Britain and New Zealand) a standardized collection process is used8 (see Appendix). The Coggins test for equine infectious anemia (EIA) needs to be performed on horses that will travel interstate. For those horses imported into the USA and which might compete internationally, tests for piroplasmosis, dourine, glanders and EIA should be performed. When breeding stock are examined, tests for equine viral arteritis and contagious endometritis may be required.8,24 In each case the client should be warned about the cost of such tests and the delays that testing might incur. Horses would ideally not be purchased until the results of such tests were known. During the clinical examination before and after exercise the cardiovascular system should be carefully examined. Chapter 32 discusses the evaluation of the cardiovascular system in detail. Principally the examiner determines if there is evidence of overt cardiac disease (elevated resting heart rate, elevated resting respiratory rate, distended jugular veins, dependent edema and exercise intolerance) cardiac murmurs or cardiac arrhythmias. Second, it is important to differentiate between physiologic cardiac murmurs and arrhythmias and those that are pathologic. Where there is doubt, an electrocardiographic examination and an echocardiographic examination may be required. It is advisable to seek specialist opinion in these areas. The following points should be kept in mind:26 • Physiologic murmurs (flow murmurs) are usually localized, of low intensity (grade 1 and 2), short in duration and sometimes musical. They are usually early to mid systolic, early diastolic or presystolic. • Pathologic murmurs are often (but not always) louder, radiating and holo-pansystolic (mitral and tricuspid valve regurgitation) or holodiastolic (aortic valve regurgitation). • Mild localized regurgitant murmurs may be associated with a low risk for athletic performance. Echocardiography is best. • Sinus arrhythmia, sinus block and second-degree atrioventricular block are relatively common and of no clinical significance. • Atrial fibrillation and premature beats (atrial premature complexes, ventricular premature complexes) are usually not acceptable in athletic animals. Exercise or 24-hour electrocardiographic examinations may be required to determine clinical significance. • Imaging and the prepurchase examination. • The most common ancillary diagnostic aid used to evaluate the musculoskeletal system in the prepurchase examination is radiography. Radiography was performed in 49% of all prepurchase evalutions in one review27 and this was more likely if the examination was performed at a clinic. The principal indications or reasons for prepurchase radiography include:28 • Clinical examination findings indicating an abnormality that requires quantification/clarification (e.g. fetlock joint effusion with pain on flexion). • Intended use of horse (e.g. dressage competitor versus low-level pleasure horse). • In young unbroken horses or in horses unable to be rigorously exercised, or athletic horses that have been rested, survey radiographs may help identify clinically silent or quiescent lesions which may cause future problems when training starts or is recommenced. • Client’s instructions. Clients may instruct the examining veterinarian to perform a radiographic examination. The reasons for this can be many and include the desire to sell the horse in the future, previous bad experiences or because of advice from others.28 • A standard set of radiographs is required as part of the examination of Thoroughbred horses being exported for racing to some countries (e.g. Hong Kong and Macau). • The routine use of radiography in the prepurchase examination can be problematic. Opinions differ as to the reliability of radiographs to be of predictive value for future athletic soundness.28 Some veterinarians believe that radiography should be avoided if it will not influence the opinion given on clinical grounds. The added expense and the possibility that radiographs will only ‘confuse the picture’ especially if questionable changes are identified should also be considered. Regardless of these issues, radiographic lesions or changes can only be properly interpreted when combined with examination findings and clinical history. Radiographs by themselves may be meaningless. In addition, high-quality images with sufficient views are required.29,30 The minimum number of radiographic views required to examine a specific anatomical site during prepurchase radiography are presented in Table 60.1.28–30 The radiographs must be permanently marked with the name or number of the horse, date, name of the veterinarian or veterinary hospital and identification of the leg examined. A method for recognizing which oblique view has been taken (e.g. always placing markers on the lateral aspect of the film) is necessary. The radiographs belong to the veterinarian and are part of the animal’s medical record and need to be kept for the period determined by the statute of limitations for the state or locality in which the veterinarian lives. Table 60.1 Minimum recommended radiographic views for prepurchase radiography aBy angling the X-ray beam distally by 5° in the front fetlocks and 10° in the hind fetlocks the palmar or plantar aspect of the proximal phalanx can be clearly visualized to identify bone fragments at this site. When viewing radiographs during the prepurchase examination a thorough examination of each film is performed.31 Significant radiographic abnormalities associated with the appendicular skeleton of the horse have been reviewed.31 Any abnormalities should be described in terms of size, shape, position, density and relationship to adjacent structures. With respect to the athlete, however, there are a number of recognized conditions or anomalies observed on radiographs that carry a degree of risk for reduced athletic performance (Table 60.2).28,29,31 The examiner should look carefully for the presence of developmental orthopedic disease (age, breed and joint specific), osteoarthritis or evidence of ‘wear and tear’, fracture and bone modeling. In young untrained animals developmental orthopedic disease must be conscientiously ruled out. In animals that have performed, especially older animals, osteoarthritis and ‘wear and tear’ injuries are important. Table 60.2 Estimate of risk that various observed radiological changes result in reduced athletic performancea,b • Pedal osteitis complex/concussive trauma31– moderate – manageable. • Hoof imbalance – low to moderate – manageable. • Osteoarthritis (OA) distal interphalangeal joint31 – high. • P3 Osseous cyst-like lesions31 – if communicate with joint risk is high. Upright pedal or D45° Pr-Pa (PL) DiO required. • Ossification of hoof cartilages31 – low. • Mineralized opacities adjacent to extensor process of P328,31 – low, usually insignificant. • Round smooth densities adjacent to palmar processes – low, secondary centers of ossification or old fracture.31,34 • Increased number of enlarged synovial fossae. • Medullary sclerosis/loss in corticomedullary definition. • Flexor cortex erosions/new bone formation. • Distal border fragments and palmar cortical thickening. • The above changes in combination with clinical findings are indicative of navicular disease/syndrome which represents a high risk for impairment in future athletic performance. • DJD – generally risk is high. Dorsal proximal P2 osteophytes may be incidental in Warmbloods.8 • Osseous cyst-like lesions (distal P1 or proximal P2) – risk is high if communicate with proximal interphalangeal joint (especially if medial or lateral of midline) and if accompanying evidence of OA, low if isolated from joint. Centrally located cyst-like lesions in the distal aspect of P1 in yearling Thoroughbreds appear to have a low risk for future lameness unless they are large.36 • Osteochondral fragments palmar/plantar eminence of proximal P2 – risk is low–moderate.37 • DJD31 – Generally risk is moderate–high in any performance horse. If supracondylar lysis and osteophyte formation on the sesamoid bones are present, risk is high. Reduced risk if only slight modeling, correlate with age, occupation and clinical findings. • Palmar/plantar proximal P1 fragments – origin may be proximal sesamoid bones or P1, can be articular or non-articular and could be avulsion fragments or OCD. Risk is considered low and articular fragments can be removed arthroscopically with a good prognosis. Little effect on ability to start a race (presale findings in Thoroughbred yearlings9) and little effect on racing performance in Standardbreds.38 • Ununited proximoplantar tuberosity – suggested clinical significance 12.5%39 when recognized in young animals. May heal back to parent bone in young animals. Correlate with exam findings. Evidence of periosteal proliferation, calcification of distal sesamoidean ligaments and articular involvement increases risk. • Proximal dorsal P1 fragments – possibly developmental in yearlings but most likely traumatic in adults. Risk is low if performance history is good and other signs of OA are absent. Correlate with age, occupation and exam findings. Prognosis following arthroscopic removal is very good.9,29,31 In Thoroughbred yearlings hindlimb P1 fragments were associated with a reduced chance to race at two or three years.9 and P1 fragments reduced yearling sales price in one study.40 • OCD – distal MC3/MT3 and distal 2/3 of MC3/Mt3 sagittal ridge9 – risk is variable. Large defects, those with fragments and those showing subchondral bone changes represent a moderate–high risk. Follow-up on yearling Thoroughbreds and Standardbreds showed these changes to have little effect on starting a race (Thoroughbred) or on racing career (Standardbred) – amenable to surgery with a reasonable prognosis.9,29 Large lesions of the mid sagittal ridge (>10 mm long) in hind fetlocks in Thoroughbred yearlings were associated with reduced racing performance at two and three years.41 • Osseous cyst-like lesions of Mc3/Mt3 and proximal P1 – risk is high if communicate with articular surface. Some cysts, however, can be incidental findings.29 • Sesamoiditis31 – conflicting opinion and research evidence on risk. Proposed etiology varies between occupations.31,42–45 Radiological changes include osteophytes, enthesophytes, osteolysis and enlarged vascular channels. If multiple changes then ultrasound of suspensory apparatus is warranted. Correlate with age, occupation, conformation (e.g. upright pasterns), exercise history and exam findings. Increased numbers of enlarged, irregular vascular channels especially if enthesophytes are present represent an increased risk.9,45 Check for DJD of fetlock joint. In one study presale radiography of Thoroughbred yearlings showed >50% of proximal sesamoid bones had irregular vascular channels but this did not affect the ability of horses to start a race when two or three years old.9 but in another study the presence of more than two irregularly shaped vascular channels was associated with less earnings and starts when two and three years of age.46 Proximal sesamoid modeling in both front and hind fetlocks in Thoroughbred yearlings has been associated with reduced performance.9,41 Young Standardbreds with sesamoid changes showed improvement over time and earnings as three- and four-year-old horses were not different to those horses without sesamoid changes.44 • Fractures43 – sesamoid fractures identified on presale radiographs of yearling Thoroughbreds did not appear to influence the ability to start a race at two or three years of age in one study.9 In another study forelimb sesamoid fractures were associated with less chance of starting a race at two or three years.41 These fractures (some of which may be separate centers of ossification), often occur when the horse is a foal and healing can result in a complete bony union.43 An elongated or malshaped sesamoid bone can result if the fracture was displaced. Ability to start a race was not affected by these changes.9 Hindlimb apical sesamoid fractures in particular appear to be low risk.9 Fracture size, position and evidence of other changes should be evaluated in young horses to estimate risk. Prognosis is excellent for racing after arthroscopic removal of apical sesamoid fractures in weanlings or yearlings involving the hindlimbs and lateral forelimb but reduced for medial forelimb fractures.47 In mature horses sesamoid fractures are often clinically significant and careful evaluation of the suspensory apparatus and fetlock joint is required. • Exostoses/splints31 – active splints represent a short-term moderate–high risk for impaired athletic performance. Palmar soft tissues may require ultrasonography. • Proximal MT3/MC3 sclerosis31 – may alert clinician to conduct an ultrasound of the proximal suspensory ligament but the presence of this change alone may have little clinical significance. • DJD31 – generally risk is moderate–high for any performance horse. Mild changes, including mild articular osteophyte production, especially in the radiocarpal joint, have reduced risk. Assess with respect to age, conformation, occupation, work history and intended use. Smooth/mature non-articular enthesous bone formation on dorsal carpal bones – low risk.28 Some third carpal bone sclerosis in racehorses is expected. Significant focal lucency and marked loss of trabecular pattern – high risk. Presale radiography of yearling Thoroughbred racehorses showed the presence of dorsal medial intercarpal disease reduced the chance of starting a race at age two or three by 20%.9 A more recent study showed no affect on performance.41 • Dorsal proximal accessory carpal bone fractures – Identified in yearling Thoroughbred presale radiographs and were shown to affect earnings potential as two and three year old racehorses. Prognosis is reduced if accompanied by mild dorsal peri-articular changes of the radiocarpal joint.48 • Osseous cyst-like lesions – can affect any of the carpal bones, usually incidental findings.28 Osseous cyst-like lesions of the radial carpal bone or distal radius may cause lameness – correlate with clinical signs. • OA (tarso-metatarsal and distal intertarsal joints)31 – Generally risk is moderate–high for any performance horse. Assessment of risk can be difficult based on radiographs alone because correlation between radiographic findings and lameness is poor. Therefore, clinical examination, age, occupation and exercise history is important. Smooth mineralized enthetic osteophytes on the dorsoproximal aspect of MT3 may be incidental findings without other articular changes – risk is low.29 Thoroughbred yearlings with evidence of osteophyte or enthesophyte formation at the distal intertarsal or tarso-metatarsal joint margins were significantly less likely to start as two or three year olds (difference was 7%).9 The presence of periarticular osteophytes dorsomedially in Icelandic Ponies had a 53% predictive value for lameness.49 • OCD31 – generally risk for affecting athletic performance is considered low–moderate but site, size, subchondral bone changes and other joint changes should be considered. Studies in conservatively treated Standardbred racehorses that were evaluated as young horses show racing performance to be similar to unaffected horses.38,50 Other studies show mild reductions in earnings and numbers of starts (especially in two year olds).51,52 Small or well-attached fragments are low risk but effusion and lameness may result (unpredictably) when workload increases.28 Evidence of OCD of the tarsus had little effect on the ability of a Thoroughbred yearling to start as a two or three year old.9,41 Success rates following arthroscopic surgery are good (75–80%).53 • Wedged, third and/or central tarsal bones – represents a moderate–high risk for reduced athletic peformance and may predispose to fractures.54 Check for associated OA. • OCD (osteochondritis dissecans)31 – most horses show clinical signs within the first two years of life. However, clinical signs can manifest at any age. In addition, radiographic changes may correlate poorly with intra-articular pathology. Therefore, clinical examination findings are most important and should be assessed together with site, size, subchondral bone change, presence of concurrent OA, age, occupation and exercise history to assess risk. Mild changes (flattening, irregularity) without effusion – low risk. Larger lesions have higher risk. Prognosis for successful athletic performance following arthroscopy for femoropatellar osteochondritis dissecans is 62–82%.53,55 • Subchondral cystic lesions (SCL) – although some SCLs may be asymptomatic, all SCLs of the stifle (medial femoral condyle, proximal tibia) potentially have a moderate to high risk for affecting future athletic performance because the occurrence of associated lameness is unpredictable. Communication with the articular surface increases the risk. Interpretation of SCLs in asymptomatic yearling Thoroughbreds is problematic. One study showed no effect on racing performance between 2 and 4 years of age in horses with subchondral bone cysts (SBC) or subcondral cystic lesions.56 In another study Thoroughbred yearlings with a SBC >6 mm deep had a reduced likliehood of starting a race at two and three years of age.41 In addition, the results of surgical therapy can vary – arthroscopic debridement carries a 30–74% success rate for successful athletic performance.57–59 Intra-lesional cortisone therapy in Thoroughbreds showed 81% of horses returned to athletic performance.60 Shallow concavities of the distal medial femoral condyle without underlying subchondral changes on the articular surface are generally thought to be low risk.28 aAll conditions should be assessed in light of the clinical examination. Only rarely do radiographic lesions by themselves allow a complete assessment of risk. Assessment of risk has been generalized for each condition. However, each horse should be evaluated as an individual. bCited references describe aspects of the radiographic, radiological or clinical features of each condition. Radiographic evaluation in the prepurchase environment has a number of limitations and these should be discussed with the purchaser. Routine radiographic views may not detect all lesions, apparently normal radiographs do not always exclude pathological processes (e.g. developing lesions may not be detected) and apparently abnormal findings may not have current or future clinical relevance. For example, Figure 60.1

Examination of the equine athlete prior to purchase

Introduction

Aim and philosophy

Requirements for the prepurchase examination

Examination procedure

Stage 1. Preliminary examination

Stage 2. Examination during walking, trotting, turning and backing

Stage 3. Examination during and immediately after strenuous exercise

Avoiding problems in the prepurchase examination

Special considerations and ancillary tests

Conformation assessment

Laboratory evaluation

Examination of the cardiovascular system

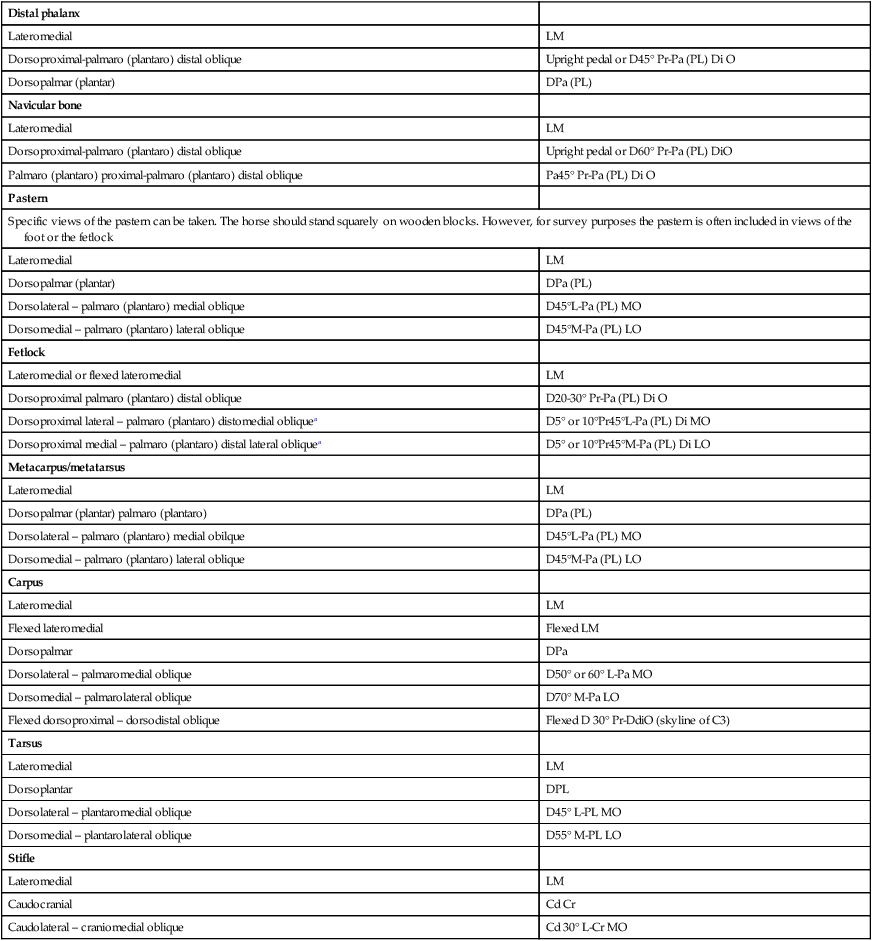

Distal phalanx

Lateromedial

LM

Dorsoproximal-palmaro (plantaro) distal oblique

Upright pedal or D45° Pr-Pa (PL) Di O

Dorsopalmar (plantar)

DPa (PL)

Navicular bone

Lateromedial

LM

Dorsoproximal-palmaro (plantaro) distal oblique

Upright pedal or D60° Pr-Pa (PL) DiO

Palmaro (plantaro) proximal-palmaro (plantaro) distal oblique

Pa45° Pr-Pa (PL) Di O

Pastern

Specific views of the pastern can be taken. The horse should stand squarely on wooden blocks. However, for survey purposes the pastern is often included in views of the foot or the fetlock

Lateromedial

LM

Dorsopalmar (plantar)

DPa (PL)

Dorsolateral – palmaro (plantaro) medial oblique

D45°L-Pa (PL) MO

Dorsomedial – palmaro (plantaro) lateral oblique

D45°M-Pa (PL) LO

Fetlock

Lateromedial or flexed lateromedial

LM

Dorsoproximal palmaro (plantaro) distal oblique

D20-30° Pr-Pa (PL) Di O

Dorsoproximal lateral – palmaro (plantaro) distomedial obliquea

D5° or 10°Pr45°L-Pa (PL) Di MO

Dorsoproximal medial – palmaro (plantaro) distal lateral obliquea

D5° or 10°Pr45°M-Pa (PL) Di LO

Metacarpus/metatarsus

Lateromedial

LM

Dorsopalmar (plantar) palmaro (plantaro)

DPa (PL)

Dorsolateral – palmaro (plantaro) medial obilque

D45°L-Pa (PL) MO

Dorsomedial – palmaro (plantaro) lateral oblique

D45°M-Pa (PL) LO

Carpus

Lateromedial

LM

Flexed lateromedial

Flexed LM

Dorsopalmar

DPa

Dorsolateral – palmaromedial oblique

D50° or 60° L-Pa MO

Dorsomedial – palmarolateral oblique

D70° M-Pa LO

Flexed dorsoproximal – dorsodistal oblique

Flexed D 30° Pr-DdiO (skyline of C3)

Tarsus

Lateromedial

LM

Dorsoplantar

DPL

Dorsolateral – plantaromedial oblique

D45° L-PL MO

Dorsomedial – plantarolateral oblique

D55° M-PL LO

Stifle

Lateromedial

LM

Caudocranial

Cd Cr

Caudolateral – craniomedial oblique

Cd 30° L-Cr MO

What are we looking for on prepurchase radiographs that may result in a reduced capacity to perform as an athlete?

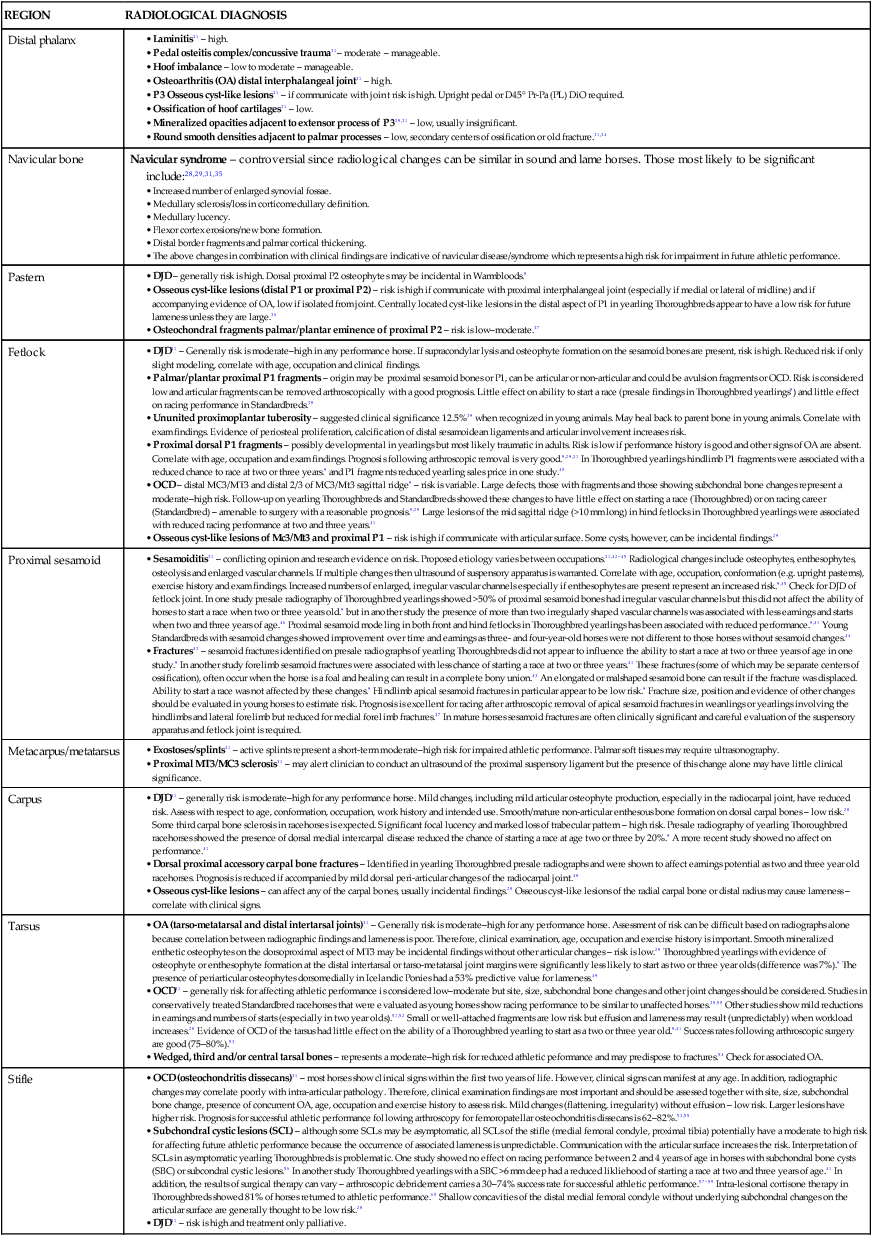

REGION

RADIOLOGICAL DIAGNOSIS

Distal phalanx

Navicular bone

Navicular syndrome – controversial since radiological changes can be similar in sound and lame horses. Those most likely to be significant include:28,29,31,35

Pastern

Fetlock

Proximal sesamoid

Metacarpus/metatarsus

Carpus

Tarsus

Stifle

Limitations and problems associated with prepurchase radiographs

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Examination of the equine athlete prior to purchase