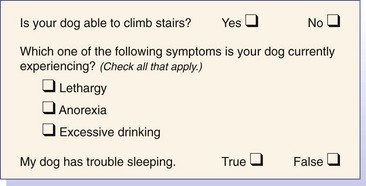

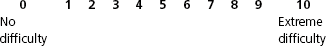

Chapter 11 For this question, the focus will be on problems with the question itself: Problem No. 1: This is what is known as a double-barreled question, that is, it actually asks two different questions at once. It is asking an owner “How much difficulty does your dog have going up the stairs?” and “How much difficulty does your dog have going down the stairs?” The answer may not be the same for both. For example, dogs with front limb orthopedic disease often will have more difficulty going down the stairs, and dogs with hindlimb orthopedic disease will have greater difficulty going up the stairs. So how will an owner of a dog with elbow osteoarthritis answer this question, if the dog goes up the stairs relatively easily, but has more difficulty going down? Will he choose to average the difficulty of the two activities, or will he choose the most extreme value of the two? If the owner is asked this question again later in the course of the study, will he use the same thought process to answer the question? Problem No. 2: How will an owner answer this question if the dog does not live in an environment with stairs? Many dogs, depending on geography or the physical abilities of their owners, live in an environment without stairs. Will the owners of these dogs make a “guess” as to how much difficulty their dog would have if it did live in an environment with stairs? Will these owners just choose to leave the question blank and then leave it up to the investigators to manage missing data? Problem No. 3: Over what time frame should the owner make this assessment—today, the past week, the past month? Many conditions have a waxing and waning clinical course (i.e., “good days” and “bad days”). If an owner of a dog with coxofemoral osteoarthritis is asked this question, will he choose the worst of the dog’s most recent days, or will he average some series of days? For this question, the focus will be on problems with the response options: Problem No. 1: Some of the response options are asking for an assessment of change, while others are asking for a current assessment of health status. If a question is to be used to assess change, two options are available. The first option is to assess the current health status of the animal at two different points in time during the study, and then calculate the change. The second option is to ask about change at some point following an intervention or during the progression or resolution of disease. Mixing both types of responses in the same question causes confusion for the respondent. Problem No. 2: Response options do not cover all of the possible choices for which the owner may be looking. Two “change” options are provided: “no change” and “increased,” but no option is given for “decreased.” Three health status options are listed: “indifferent,” “little attention,” and “needy”; no options are offered for a normal or average amount of attention, or for a lot of attention without the negative connotation of being needy. Problem No. 3: The response options are not mutually exclusive. If a dog pays little attention to the family, but that is not any different than the dog’s normal behavior, will the owner choose option number 2 or option number 4? If the owner circles both on the questionnaire, how will the investigator manage the data? Step One: Devising the Items (Questions) The first step in designing a scale or questionnaire is devising the questions themselves. This is far from a trivial task in that no amount of statistical manipulation after the fact can compensate for poorly chosen questions, that is, those that are badly worded, ambiguous, irrelevant, or even not present.13 Two of the more relevant techniques for developing questions in a rigorous and systematic manner include the use of focus groups and key informant interviews. Focus groups are discussions in which a small group of people (typically six to twelve) with traits of interest are guided by a facilitator to talk about themes that are important to the investigation. For example, if one wanted to develop an outcome assessment scale to measure the ability of dogs with osteoarthritis to function in their home environment, owners of dogs with osteoarthritis would be assembled to discuss the behaviors they associate with their dog’s ability to function and how their dog’s osteoarthritis affects those behaviors. Key informant interviews are interviews with a small number of people who possess unique knowledge. These could be owners of animals with the condition of interest, but usually the group consists of three to ten clinicians who have extensive experience evaluating and managing those patients. Once a series of questions has been devised, a method by which the responses will be obtained must be chosen. This is dictated in part by the nature of the question, but a very large body of research in this area describes the advantages and disadvantages of the wide variety of scaling methods that can be used. One form of question frequently used requires only a categorical judgment by the respondent, indicated by a “yes/no” response or a simple check. This results in a nominal scale (Figure 11-1). However, many of the variables of interest to health care researchers are continuous rather than categorical, and many options for scaling these responses may be chosen. The visual analogue scale is a line of fixed length with anchors at the extreme ends and with no words describing the intermediate positions (Figure 11-2). Respondents place a mark on the line corresponding to their perceived state. This approach is simple for investigators but often is not well understood or completed appropriately by respondents, and other methods may yield more precise measurement.3,6,7,13 To minimize the problems that arise when some respondents inappropriately complete visual analogue scales, those response options can be converted relatively easily to numeric rating scales by converting the visual analogue line to a 0 to 10 choice, as in the example (Figure 11-3). Adjectival scales use descriptors along a continuum rather than simply labeling the endpoints (Figure 11-4). Likert scales are bipolar scales measuring a continuum of positive to negative responses to a statement (Figure 11-5). When Likert scales are constructed, consideration should be given to several issues, such as the number of scale divisions to provide, and whether or not a neutral category should be included. For example, sometimes it is desirable to use a four- or six-point scale and exclude the neutral response option, to force the respondent to make a choice in the negative or positive direction.

Evidence-Based Medicine and Outcomes Assessment

Outcome Assessment in Veterinary Medicine

Stepwise Development of a Health Measurement Instrument*

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Evidence-Based Medicine and Outcomes Assessment

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue