Chapter 7 Endoscopic Removal of Gastrointestinal Foreign Bodies

Anatomic Considerations

Foreign bodies become impacted in the gastrointestinal tract at both normal anatomic and pathologic points of narrowing. The major factors that determine whether a foreign body will pass uneventfully or be retained are its size and configuration (e.g., rough versus smooth edges, presence or absence of projections, and width). Once pointed objects (e.g., needles or wishbones) are beyond the oropharynx, they occasionally become lodged in the pyriform processes. These areas can be seen with an endoscope but are best evaluated with a laryngoscope.

Patient Profiles

Although foreign body ingestion is certainly more common in young animals than middle-aged to older animals, the possibility of a foreign body–related disorder must always be considered in any animal with suggestive signs. We have seen many cases of older animals with endocrinopathies causing polyphagia or intestinal disease causing pica that present with gastrointestinal foreign body impactions. Most commonly, foreign bodies are ingested during a foray through garbage (“dietary indiscretion”) or when an animal is playing (e.g., whole or partial sections of toys chewed and eaten, balls swallowed suddenly after being caught in flight, or fishhooks and needles ingested during an inquisitive investigation). Dogs that chew rocks occasionally swallow partial or whole rocks, which may then become retained in the gastrointestinal tract. In some instances an animal ingests an object for no readily apparent reason. Included in our case files are such examples as an ingested 11-cm potato nail (see Figure 7-39, C), a rigid patch of leather ingested by a cat (see Figure 7-33), and an accumulation of ingested pine needles that caused gastric impaction in a cat (see Figure 7-38). These and many other interesting cases were successfully managed by endoscopy-guided retrieval.

Our physician counterparts encounter two dissimilar patient population profiles when dealing with foreign bodies. In most instances, ingestion of foreign bodies occurs in children, particularly between 1 and 5 years of age, who swallow objects accidentally. Most of these foreign bodies tend to be small, blunt, and nontoxic (e.g., coins or small toys) and pass without intervention. In contrast, five groups of adults have been identified as being prone to ingesting foreign bodies or to suffer from impaction of food boluses. These five groups include persons with preexisting esophageal disease (e.g., stricture, diverticulum, motility disorder, or neoplasia) or gastric disease (e.g., postgastrectomy or hiatal hernia), alcoholics, psychopaths, mentally retarded handicapped persons, and prisoners. Older adults (greater than 60 years) are much more likely to have food bolus foreign bodies. Young adults (less than 40 years) are more likely to ingest true foreign bodies (inorganic objects). It is not uncommon for prisoners and persons with psychiatric disorders to intentionally swallow a foreign body as a manipulative measure. The resulting hospital admission period with endoscopic therapy is preferable to prison or institutionalization.

Clinical Signs

Gastric foreign bodies are commonly associated with partial or complete outlet obstruction with accompanying characteristic symptoms. If the foreign object is freely movable, vomiting may occur only intermittently, and especially if the object is small, there may be many days when the animal displays no clinical signs whatsoever. Large foreign bodies are usually associated with frequent vomiting, and signs are usually most pronounced when the foreign body lodges in the antrum. Occasionally a tubular hairball lodges in the pyloric canal, causing complete outflow obstruction and frequent vomiting (see Figure 4-110). The presence of a gastric foreign body may also cause inappetence or complete anorexia, malaise, and nonspecific mild abdominal tenderness. The combination of pain and fever suggests perforation, which may be associated with signs of peritonitis or which may be walled off with minimal or no abdominal signs evident. Toxic foreign objects may cause other clinical signs such as seizures (e.g., seizure activity related to lead toxicity) or hemolysis (e.g., zinc from pennies minted after 1982, nails, zippers, or jewelry containing zinc). Small disk batteries used as an energy source for watches, hearing aids, and cameras contain alkali, such as potassium hydroxide, and the heavy metals mercury and cadmium. Toxicity depends on the leakage of these substances from their casings, the duration of contact with the mucosa, and the inherent toxicity of the chemicals themselves. Endoscopic or surgical removal of a toxic foreign body is mandatory if the object remains in the stomach for longer than 24 hours or if it lodges in the intestinal tract.

Diagnostic Evaluation

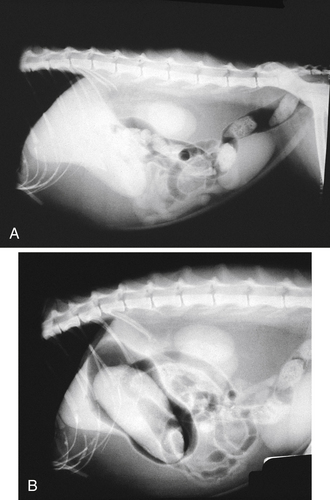

Many commonly ingested foreign bodies (fish bones, plastic, and wood) are not radiopaque and therefore pose a significant diagnostic challenge. Some foreign bodies may be composed of both radiopaque and radiolucent materials, and as a result their size may be underestimated on survey radiographs. Stomach size is important in the assessment of radiolucent gastric foreign bodies. Gastric distension is a finding compatible with a long-standing gastric foreign body. Increased width of a localized portion of the stomach, attributable to an inability of the stomach to collapse in the involved segment, is seen with foreign bodies of lesser duration. A negative contrast gastrogram is useful in cases of a suspected radiolucent foreign body (Figure 7-1) because it may help outline a foreign body and because a negative contrast agent such as air will not mask foreign bodies as barium tends to do. A nonionic iodinated contrast agent (e.g., iohexol [Omnipaque]) can also be used in an attempt to outline a suspected esophageal or gastric foreign body. Because of the hypertonic nature of ionic contrast agents (e.g., diatrizoate [Hypaque]), a nonionic iodinated contrast agent should be used so that the chance of complications is decreased; for example, volume depletion may occur when an ionic contrast agent is given orally, and pulmonary edema may occur if the agent is aspirated.

Overview of Treatment of Ingested Foreign Bodies

Sharp or pointed objects, such as pieces of plastic, needles, and safety pins, should be removed from the stomach endoscopically. As discussed previously, needles frequently pass through the gastrointestinal tract uneventfully, but early removal is recommended because of the increased potential for complications with such objects and the high success rate of endoscopic retrieval. Rounded or blunt gastric foreign bodies often pass spontaneously; therefore, if significant clinical signs such as frequent vomiting are not present, such patients may be managed conservatively with close observation and radiographic surveillance for 3 to 7 days. If signs of obstruction develop and the foreign body has passed out of the stomach, surgical intervention is indicated. Performing esophagoscopy and gastroscopy immediately before surgery is still recommended so that the esophagus and stomach can be quickly assessed for any injury resulting from either foreign body trauma or esophagitis secondary to reflux and vomiting or any signs of concurrent disease. If only surgery is done, these types of problems will go undetected. Although some animals can retain gastric foreign bodies for long periods of time with minimal untoward effects, it is always best to remove objects retained for a prolonged period (greater than 2 to 3 weeks) so that chronic mucosal damage is avoided.

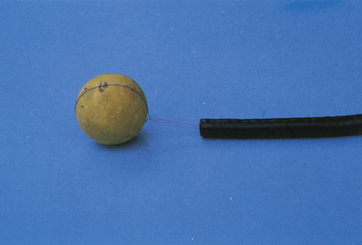

Foreign bodies that are not likely to be removed endoscopically include corncobs, large rocks (bigger than the rocks shown in Figure 7-39, A), large hard rubber balls (e.g., Superball), large wide hairballs in cats, Gorilla Glue concretions, and sometimes heavy objects such as lead sinkers. Problems with retrieval of foreign objects are related to their size in relation to the width of the grasping range of pronged foreign body retrieval instruments, the diameter of basket and snare instruments, the weight or surface texture of the foreign body, and the grasping strength and quality of the foreign body retrieval instruments being used. Smooth objects are sometimes difficult to grasp firmly enough for retrieval through the narrow areas of the lower and upper esophageal sphincters. Recently, larger basket and rigid grasping instruments have been developed, and previously irretrievable objects such as golf balls can now be more routinely removed (see the “Instrumentation” section).

Instrumentation

A variety of instruments are available for foreign body retrieval. A laryngoscope and forceps (e.g., Kelly clamp, sponge forceps) should be immediately available for removing oral and pharyngeal foreign bodies and any object that is difficult to pull through the upper esophageal sphincter with standard prong-type endoscopic grasping instruments. Until the 1970s the rigid endoscope was always used for retrieving esophageal foreign bodies. Today, however, the flexible endoscope is the instrument of choice because visualization and maneuverability are greatly enhanced. In some cases it might be best to use a flexible endoscope in conjunction with a rigid scope. Areas such as the stomach and duodenum, which are inaccessible to a rigid endoscope, can easily be reached with a flexible endoscope as long as it has sufficient length. Nonetheless, it is still advantageous to have several rigid scopes of different lengths and diameters available for selected esophageal bone foreign body cases and for possible use as an overtube for the flexible endoscope.

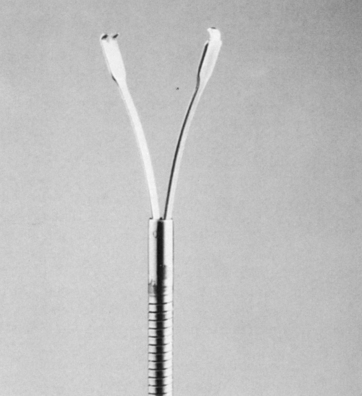

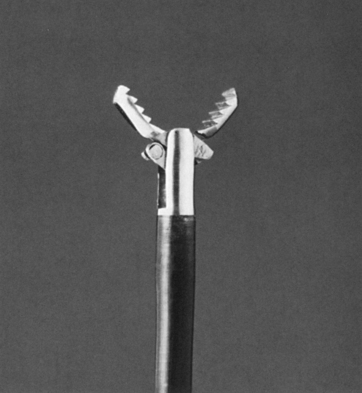

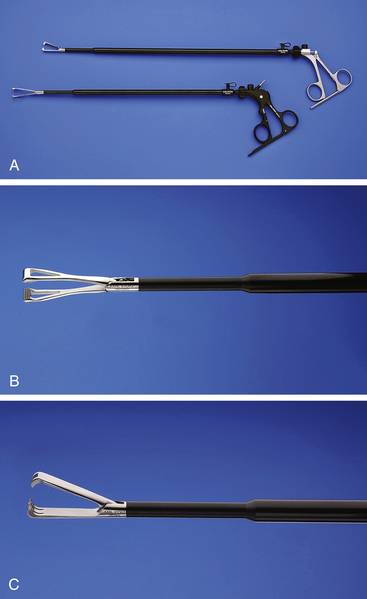

Two-, three-, and four-pronged grasping instruments are most commonly used for foreign body retrieval. A sturdy two-pronged instrument (Figure 7-2) is adequate for grasping many foreign objects and can be used with a pediatric endoscope that has a narrow working channel. Sturdy three-pronged (tripod) graspers usually require a 2.8-mm channel. Sheathed four-pronged graspers can be purchased for use in small working channels, but these instruments do not tend to be as durable. Alligator-jaw forceps (Figure 7-3) are particularly useful for grasping smooth flat objects. Rat-tooth forceps (Figure 7-4) have excellent gripping power and are especially useful for retrieving heavy cloth objects such as large socks or towels or large trichobezoars.

Figure 7-4 Sharp (rat-tooth) grasping forceps with an opening width of 4.7 mm. This instrument requires a 2.8-mm instrument channel. (The two-pronged instrument shown in Figure 7-2 can be passed through a 2-mm instrument channel.) The grasping strength of the rat-tooth forceps is excellent, and the instrument is particularly suited for retrieving heavy cloth (e.g., socks, towels) and other pliable or relatively thin objects.

(Courtesy of Olympus America, Inc., Center Valley, Pa.)

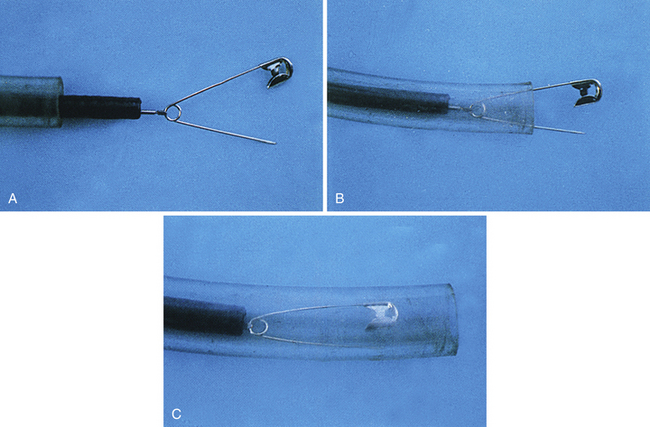

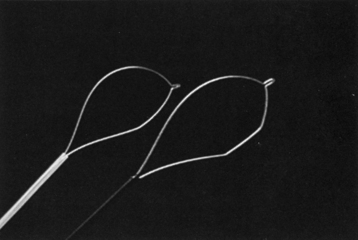

Polypectomy snares are among the most versatile instruments for removing foreign bodies (Figure 7-5). The snare loop can be extended around an object to provide a much stronger grasp than can sometimes be achieved by the single-end grasp applied by a pronged instrument. Round objects with a smooth surface (e.g., balls) are much more easily grasped with a snare than with a pronged instrument, which typically slips off the object as the prongs are closed around it (Figure 7-6). Basket retrievers (Figures 7-7 and 7-8) are less commonly required but may be a little more effective in extracting smooth, rounded objects. The large basket shown in Figure 7-8 has improved capabilities for retrieving larger objects. It was designed by Dr. Vicente Torrent, a veterinarian from Spain with extensive case experience in endoscopic removal of bones and other large objects, including many cases of golf ball ingestion. Net retrievers (Figure 7-9), such as the Roth Net, feature a flexible, durable pouch that can be helpful in the removal of round, blunt, or otherwise hard-to-grasp foreign bodies. We have found the net retriever to be useful for coin removal. When a stack of coins is present, they can often be scooped out simultaneously with a net instead of individually. Standard endoscopic biopsy forceps generally are not useful for removing foreign bodies other than thin, light objects. In fact, it is strongly advised that endoscopic biopsy instruments not be used for foreign body retrieval because such use may damage the forceps or cause the edges to become dull and thus less effective for procuring adequate-size tissue samples.

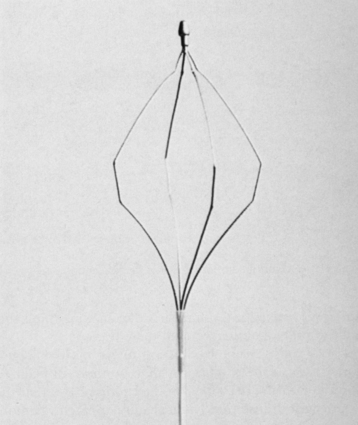

Figure 7-5 Oval (left) and crescent (right) grasping snares.

(Courtesy of Olympus America, Inc., Center Valley, Pa.)

Figure 7-7 Basket-type grasping forceps. This instrument can be passed through a 2-mm instrument channel.

(Courtesy of Olympus America, Inc., Center Valley, Pa.)

Figure 7-9 Roth Net retriever. This instrument is useful for scooping up stacks of coins.

(Courtesy of US Endoscopy, Mentor, Ohio.)

Experienced endoscopists have personal preferences regarding the types of grasping instruments they like to use in certain situations. Our advice to veterinarians who are purchasing foreign body retrieval instrumentation is to obtain high-quality sturdy instruments that are built to last. Avoid, if possible, disposable endoscopic foreign body retrieval equipment as it tends to be less sturdy and of lower quality. Lower quality instruments may cost less, but they tend to be somewhat less effective and less durable, and significant frustration often results from their use. A minimum of two types of instruments is advised: a two-prong grasper with long arms (see Figure 7-2) and a snare loop instrument (see Figure 7-5). Once experience has been gained, an endoscopist can successfully retrieve a majority of gastric foreign bodies with one of these two instruments. Our next preference would be a rat-tooth instrument (see Figure 7-4) if the endoscope working channel can accommodate an instrument of this size. Finally, net and basket instruments complete the basic endoscopic instrument armamentarium.

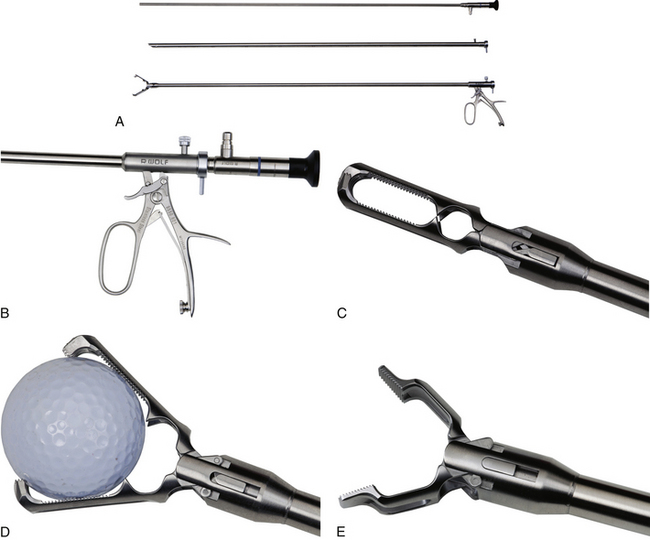

Another invaluable instrument in esophageal foreign body removal is a rigid grasping forceps designed for laparoscopic use (e.g., Duval forceps, Figure 7-10). While visualizing the foreign body using a flexible endoscope, the endoscopist advances the forceps alongside the endoscope and grasps, firmly holds, and removes the offending object. These forceps have significantly more holding power than any other piece of equipment used through the scope and have been particularly helpful in removing large bones. As they are such firm graspers, care must be taken to apply only gentle traction during removal to avoid esophageal perforation. Even larger graspers are now available for retrieving objects such as golf balls from the stomach (Figure 7-11).

The tube is first passed over the endoscope to the level of the control handle (Figure 7-12). The endoscope is then inserted in the usual manner, and the overtube is advanced as needed. The inner walls of the overtube should be well lubricated to allow easy passage of the endoscope through it. When a foreign body is being removed, the grasping forceps should withdraw the foreign body into the overtube, thereby protecting the mucosal surface (Figure 7-13). An overtube can be useful even if a sharp object cannot be completely drawn into its lumen. Because it has a wider diameter than the endoscope, the overtube serves to maintain better dilation at the lower and upper esophageal sphincters, thus making it less difficult to pull an object through these orifices.

Endoscopic Removal of Esophageal Foreign Bodies

As with any type of esophagogastroduodenoscopy procedure, the patient is maintained under general anesthesia in a left lateral recumbent position. In this position the esophagus lies above the aorta. A properly inflated endotracheal tube is especially important in preventing tracheal compression as a large foreign body is pulled retrograde through the esophagus and in preventing aspiration of any object that might be inadvertently dropped in the pharynx during retrieval. After complete oral examination, the endoscope should be passed under direct visual guidance through the pharynx and upper esophageal sphincter to avoid striking any foreign body material that may be present in the proximal esophagus and that subsequently may damage the mucosa. As the endoscope is advanced, the esophageal mucosa should be carefully evaluated for any foreign body–related damage. For enhanced visualization, air should be insufflated to distend the esophageal walls, but the patient’s respiratory status must be carefully monitored while this is done. Air may be forced around an impacted foreign body and into the stomach, which can lead to significant gastric distension with resultant respiratory and cardiovascular compromise. Cats and small dogs are most at risk. The distension should be relieved as quickly as possible. In most cases this can be done by periodically passing the endoscope or narrow diameter tubing around the foreign body and into the stomach so that the air can be suctioned. Air insufflation to a perforated esophagus can also result in acute respiratory signs. The anesthetist is advised to monitor both respiratory character and degree of gastric distension during the procedure.

Esophageal Bone Foreign Bodies

Bones are usually not easily dislodged once they become impacted in the esophagus. Wishbones are an exception, especially if the furcular process of the bone is positioned cranially. Usually one or both of the furcular rami of the bone have a sharp edge (caused by trauma during ingestion) that impales the esophageal mucosa during transit (see Figure 7-19). Once the edge becomes wedged into the esophageal wall, the wishbone is unlikely to pass. The bone is usually easily removed if the endoscopist simply grasps the furcular process with a pronged instrument, pulls it directly to the endoscope tip, and simultaneously retrieves the endoscope and bone as a unit.

Chicken, pork, or rib bones are usually more difficult to dislodge. Often a bone has been lodged for several days or more before a definitive diagnosis of esophageal obstruction is made. In most cases some degree of mucosal laceration acts as an anchoring site. Spasm of esophageal muscle may also prevent movement of the bone.

If the bone does not move in response to this initial effort (as is often the case), several procedures can be attempted. As stated previously, the endoscope tip should not be used to forcefully push against the foreign body because the scope may be damaged. An overtube can be used, however, to apply caudally directed force under direct visualization. Any force should be carefully applied. The goal at this juncture is to first disengage the bone from the esophageal wall so that it can be freely moved. Caudal force followed by grasping and pulling in short interchangeable motions may help free the foreign body. If a wide diameter rigid endoscope (e.g., proctoscope) is used, a rigid grasping instrument can be passed through it to the bone. Once a firm purchase is obtained, an attempt is made to twist the bone back and forth in short motions to disengage it from the wall. Standard flexible grasping forceps cannot be used effectively in this manner. Rigid laparoscopic or other rigid grasping forceps (see Figures 7-10 and 7-11) can also be passed alongside a flexible endoscope and are often very successful at retrieving bones from the esophagus. The grasper shown in Figure 7-11 can also be used as a rigid endoscopy examination unit.

If the esophagitis associated with foreign body impaction is particularly severe, a proton pump inhibitor is recommended as the antacid of choice (e.g., omeprazole 0.7 to 2 mg/kg [0.32 to 0.9 mg/lb] orally once daily). In these more severe cases, other medications to consider include metoclopramide (0.2 to 0.4 mg/kg [0.1 to 0.2 mg/lb] orally or subcutaneously three to four times daily) or cisapride (0.25 to 0.5 mg/kg [0.1 to 0.25 mg/lb] orally three times daily) to decrease esophageal reflux by increasing lower esophageal sphincter pressure and to promote gastric emptying. The recommended duration of drug therapy depends on the severity of mucosal damage caused by the foreign body. Mild mucosal injury should be treated for 5 to 7 days, whereas moderate to severe mucosal lesions should be treated for at least 2 to 3 weeks. If the patient has no evidence of infection (e.g., pyrexia, leukocytosis with left shift, mediastinitis, pneumonia), corticosteroids are used (e.g., prednisone 0.5 mg/kg [0.23 mg/lb] twice daily for 3 days and then tapered over the next 7 to 10 days) to decrease the fibroblastic response and stricture formation. Although no proof exists that corticosteroids are absolutely effective in this regard, their antiinflammatory effect is still likely to be of some benefit to the patient. Pain relief may also be necessary in some cases, and its thoughtful use should not be overlooked (e.g., hydromorphone, morphine, transdermal fentanyl patch, etc.).

If the esophageal mucosa has been severely damaged, periodic endoscopic surveillance during the first 1 to 3 weeks after a bone has been removed is recommended so that the esophagus can be evaluated for stricture formation (see Figure 7-20). Once weekly examination is usually adequate. If damage has been particularly severe, the first examination should be done at 3 to 5 days. If a stricture occurs, it should be treated according to the guidelines presented in Chapter 3.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree