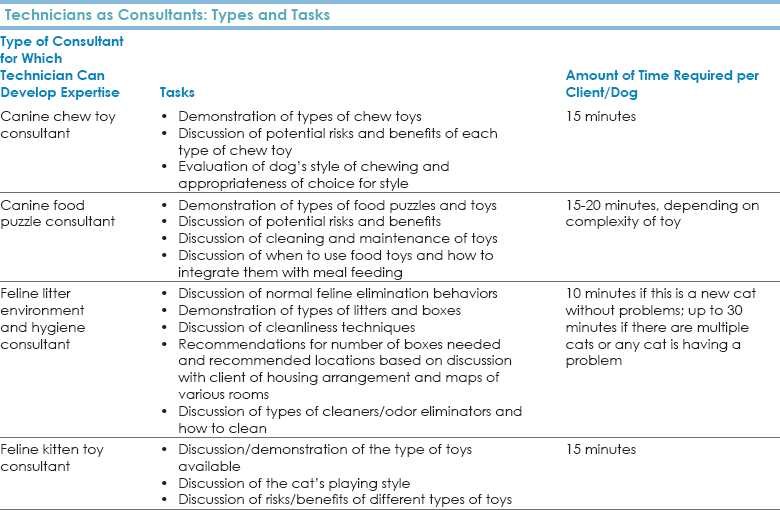

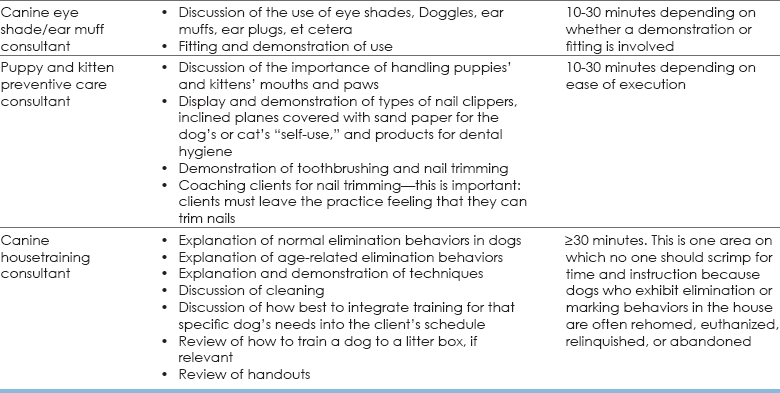

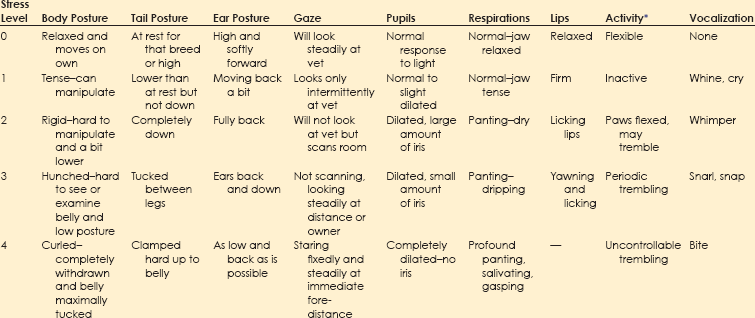

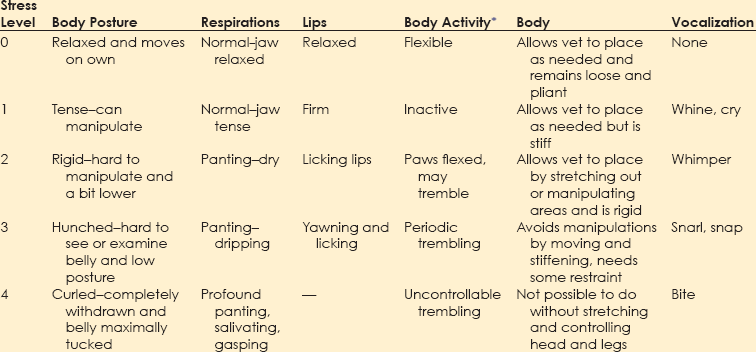

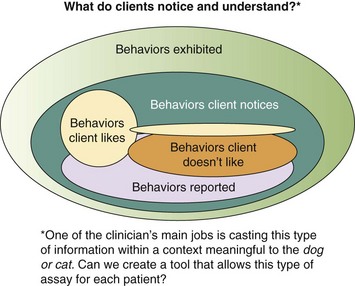

Chapter 1 Behavioral problems are still the primary reason why cats and dogs are abandoned, relinquished, or euthanized, and most of these cats and dogs are less than 3 years of age. This means that the average practice loses $2200 per relinquished cat and $3300 per relinquished dog, on average, in the most simple, basic services that are not delivered over an average 15-year lifetime. These estimates are based on the 2011 American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) estimated costs for minimum, basic, routine veterinary care.* These estimates do not include grooming, boarding, products of any kind including food, any surgery including neutering, first-year care, or any emergency care. Even at this minimal estimate, you don’t have to lose many patients to behavioral issues to realize lost income that could equate to the cost of equipment, a technician, a retirement plan, or an associate. More information about the role that behavior plays in pet loss and debility can be found in the Preface. Clients recognize that their animals are ill based on their behavioral changes. If we use any aspect of behavioral change to inform us about somatic illness, we should also be using such changes to inform us about behavioral illness. Unfortunately, clients may not know enough about behavior to identify the concerns of their cats and dogs. As noted in Figure 1-1, clients may not notice all of the behaviors exhibited by their dogs or cats and may report to the vet only behaviors they do not like, whether or not these are “abnormal.” For veterinarians to deliver the best holistic care possible, where they treat the whole dog and whole cat, they must understand when behaviors deviate from normal and how to help clients identify behaviors they like or dislike in a context that is meaningful for the dog or cat. Fig. 1-1 Conceptual diagram of how clients view cat or dog behavior. In this diagram, the set of behaviors exhibited includes ultra-normal behaviors (light color, left) through seriously pathological behaviors (dark color, right). Clients notice only a subset of behaviors, whether they are normal or abnormal. Clients are most likely to notice and report behaviors that they do not like, without regard for whether these behaviors are problems for the cat or dog. The role of veterinarians is to take this view of what clients notice and help them to interpret it in a context that is meaningful to the cat or dog. This is one of the goals of a behavior-centered practice. If we are to help clients raise and live with behaviorally healthy animals, we must be able to evaluate the normal behaviors of the dog or cat and any deviations from these. Ill animals are not behaving “normally.” In fact, clients recognize that the dog or cat is physically compromised because of some change in his or her behavior. Behavior is at the core of the practice of veterinary medicine (Martin and Taunton, 2006) and specialty practices that include behavior encourage the use of other specialties (Herron et al., 2012). The same is true for general practices. The opportunity to evaluate each patient in his or her “normal” baseline state occurs at new puppy/dog and kitten/cat visit and at wellness exams. Wellness exams should occur every few months through the first year of life; twice a year during the second year; and once a year until the dog or cat is segueing into later middle age or beginning older age, when evaluations should occur at least every 6 months (Table 1-1). This is more visits than is routinely recommended during the first 2 years of a dog’s or cat’s life, but this period of time is when the patient and his or her behavior is changing most profoundly. We need to observe cats and dogs during this time; teach clients how to observe them; and evaluate any behaviors or changes in behaviors that scare, worry, or concern clients or any member of the veterinary team. TABLE 1-1 Suggested Visit Frequency with Age for “Wellness” Appointments For initial puppy and kitten wellness appointments, 40 minutes is sufficient time to: • Accustom the puppy/kitten to the exam room and exam process • Listen to the client when you ask if he or she has specific concerns or questions • Review husbandry and care patterns in which the client is currently engaged • Make recommendations about how to amend these patterns, if needed • Provide some targeted education information; keep in mind that you will have at least two or, ideally, three puppy or kitten visits of this length and customize this information for each patient—if housetraining is the issue, your focus will be housetraining at this appointment; if chewing is the issue you will focus more on toys, supervision, and humane containment of damage at this appointment • Examine and vaccinate the puppy/kitten • Play with the puppy/kitten before and after examination; this is very important because the vaccine must come at a time when the patient is having a good time with enough time afterward to continue to have a good time Follow-up examinations may be successfully done in 20 minutes for adult animals, but this estimate assumes a healthy animal and a completely non-inquisitive client who truly needs very little information. Practices can best partition their time if they use a standardized questionnaire (see the end of this chapter) to survey the patient’s behaviors at all appointments, if some members of the staff receive special training in choosing and fitting head collars and harnesses, and if early intervention and management-related advice is provided. Depending on the problem, support staff can take the patient and client into a less busy area and help them on the spot. Otherwise, the support staff can schedule a 15- to 30-minute appointment for a harness fitting or to review a housetraining handout (Table 1-2). • It is optimal if someone on the staff, who is knowledgeable about and trained to play this role, is always available during normal working hours. Asking people to come back when their lives are already over-booked poses a risk. • If practices are going to bill for the time of the staff, all fees should be disclosed and posted and based on time. There is no mandate that posted fees are charged, but charges must be transparent in advance. Posting the cost for expertise in providing behavioral advice legitimizes the value of the service, but the fees must be commensurate with job description, talent and training, and information provided. • Some practices prefer to bundle all the fees for examinations, behavioral evaluation and coaching, and vaccinations for kittens and puppies into one package over some pre-agreed time period. If you are going to do this, make sure you post exactly what is included in the package. Are unlimited question-and-answer (Q & A) visits with the staff included for the first 3 months? Can clients see the veterinarian at no additional cost more often than for appointments scheduled with vaccines if they have concerns about physical health? What services will incur additional costs (laboratory evaluations, medications to treat illness, et cetera)? Package plans can be great practice builders and encourage terrific dialogue about behaviors. • Some practices prefer to have staff or a trainer hired for the purpose of giving weekly evening classes for clients and charge on a per-class basis (e.g., maximum of six dogs and families per 2-hour session; weekly sessions for Q & A and fittings for and coaching for use of harnesses and head collars at $25 per session). See Brammeier et al. (2006) for advice on finding and utilizing trainers in veterinary practices. • Some practices hire a trainer who will charge by the course. Courses can be divided by age and size but are best kept small (e.g., no more than six dogs or cats, with preferably two staff members). If the practice has the space to have a trainer offer basic manners courses for dogs and cats at the practice, these classes provide an income stream for toys, harnesses, and food and engage the practice staff in the commitment to behavior. • Many practices hold group classes (e.g., two kitten classes, each separated by 2 weeks, and two to three weekly puppy classes of 1 to 1.5 hours’ duration) as a “free bonus” for clients in the practice. The sole purpose of these classes is to answer questions and to allow the puppies and kittens to play and begin to learn about each other in a safe environment. The hidden advantage of this approach is that many clients have the same questions, and the group discussion of the answer is extremely informative. These clients may become their own support group while bonding to the practice. • If the practice has a lot of first-time pet clients or a lot of clients with mild or management-based problems, it may be best to hold at least one session where the pets are not present so that the clients can focus on the information delivered and the veterinary staff running the session can listen to the clients. Choice of strategy is largely a manner of practice style, but whatever strategy is chosen, everyone will benefit. Basic appointments should include a discussion of reasons some toys are preferred over others and the advantages and disadvantages of the various collars, harnesses, halters, leads, et cetera. If you have a display of these items, the display can serve to educate the client in appropriate choices and provide an income stream (Fig. 1-2), but you must also have samples available that show clients how the toys work and the harnesses fit. This approach requires that a knowledgeable and helpful staff member is always available. (If you cannot fit the harness or show how the toy works or how to clean it, a client may wonder what else you don’t know.) See Table 1-2 for a list of tasks for which technicians can be trained to act as consultants, ensuring that clients get individualized attention and the most up-to-date, accurate information. Fig. 1-2 An in-clinic display of behavioral tools (harnesses and head collars) on the lower left and toys above and to the right. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Steven Brammeier.) Recent studies have shown that veterinarians, similar to physicians for humans, are not taught how to talk to clients in a manner that extracts important information while showing compassion and empathy. Clients cannot evaluate your medical skills; however, they can evaluate your ability to convey information, understand their concerns, and show empathy, and they do so on the basis, in part, of how well you listen. In one study, the median and mean lengths of time clients talked before being interrupted by the veterinarian were 11 seconds and 15.3 seconds (Dysart et al., 2011). Be conscious of this finding. Set a timer for a minute and see if you can allow the client to speak that long without interruption. If you are having trouble not interrupting, try sitting down. It’s easier not to interrupt if you are not standing. • How did you get this cat/dog/puppy/kitten? Impulse buys or emotionally impulsive adoptions can work out, but it’s important to assess whether the client has the knowledge base to care for the animal. • Where did you get the pet? There are good public health reasons for asking this question. If the client has young children and a kitten is wormy and flea infested, both Toxocara and cat-scratch disease could be concerns. • Why did you choose this specific animal (i.e., type of pet or breed)? Many people didn’t make a choice, but if they did, chances are you will learn about something that is important to the client by asking. • What are you feeding your new pet, and how do you think he or she is doing on that diet? This gives you a chance to combine behavioral advice (e.g., perhaps the kitten could have some or all of his dry food in a food ball) with nutritional advice. • Have you noticed any problems with elimination? This question allows you to combine behavioral and medical advice and observations. • Are there any behaviors about which you are concerned? Combined with the previous information, this question will help you to round out your understanding of the client’s needs and knowledge base. • Do you have any questions about anything pertaining to this new pet? Listen first. Probe and respond second. • Samples of size- and style-appropriate toys can be included. • Consider including the following handouts: • Treats and foods chosen for the breed and size of dog/cat can be provided in a small bag. Sources can be provided on an information sheet. • Information on housetraining/litterboxes and choosing and using leads, harnesses, collars, et cetera, can be very helpful. • Consider including the following handouts: • “Protocol for Choosing Collars, Head Collars, Harnesses, and Leads” • “Protocol for Basic Manners Training and Housetraining for New Dogs and Puppies” • “Protocol for Understanding and Treating Cats with Elimination Disorders and Elimination Behaviors That Concern Clients” • “Protocol for Understanding Odd, Curious, and Annoying Feline Behavior” • “Protocol for Understanding and Managing Odd, Curious, and Annoying Canine Behaviors” • “Protocol for Generalized Discharge Instructions for Dogs with Behavioral Concerns” • Include vaccination schedules, wellness schedules, and appointments already made in a calendar form that will encourage clients to add these to their calendar and/or stick them on the refrigerator. • If the pet is of a type that might need a lot of grooming or special grooming, samples of dermatologically friendly shampoos can be included, along with a list of websites where good grooming products can be found. • Suggestions for exercise should be tailored to the individual pet, but locations of dog parks or websites with information on hobby sports (yes, agility is a sport for cats, too) can be prepared by your practice staff and included for each new patient. • Microchipping can help keep pets safer. Include information early in the sequence of visits and remind clients that shelters scan for microchips and will hold identified patients. One study examined the behavior of dogs at veterinary hospitals and found that 106 of 135 (78.5%) dogs were fearful on the examination table (Döring et al., 2009). Of the dogs, 18 (13.3%) had to be dragged or carried into the practice; fewer than half of the dogs entered the practice calmly. Dogs who had had only positive experiences were less fearful than others, and dogs less than 2 years of age—who see vets often—were more fearful than older dogs—who see vets infrequently, suggesting that repeated exposure to veterinary practices may enhance fear to a certain age. 1. We need to distinguish patients for whom early fear is a true pathological diagnosis from patients who are just afraid of what we are doing to them and where we are doing it. If most of our patients are afraid, we cannot adequately evaluate their early behaviors. 2. Although we can man-handle puppies/kittens and—usually falsely—dismiss fear as “normal,” to do so sends the wrong message to the patient and to the client. We must realize that: a. We should not man-handle anyone. b. We will not be able to man-handle many of these patients as they age and grow without the greatly increased costs incurred by staff time, the effects of stress, and job-related injuries. c. Modern zoos have abandoned forceful handling. Children’s hospitals are now open, engaging places where kids participate in the delivery of their care. Why are we still struggling with our veterinary patients? 3. The delivery of veterinary care may teach cats and dogs that humans can be threatening. This realization will contribute to the development or worsening of any behavioral problem. These three factors suggest that, unwittingly and without malicious intent, the delivery of veterinary care can be a causal factor in the worsening of patients’ behaviors. • These babies will never have encountered the noise range and frequency that defines a busy veterinary practice. • The general lighting is different and often invasive, and it’s unlikely anyone has looked in the patient’s eyes with a penlight. • The global odor must be complex. Even if these puppies/kittens were born in a home with lots of animals, they have never faced so many and such diverse smells at once. • Most puppies/kittens will never have had the social experience of encountering so many humans and animals at once and in such close quarters. • Many puppies/kittens may be walking for the first time on flooring that will steal their balance and traction. • Finally, if the client is clutching at the patient or at his or her “restraints” (e.g., leads, harnesses, carriers, collars), the patient can only take this as a signal to react. Is it any wonder that most animals never show their true behaviors at most veterinary visits? Arousal levels are key to understanding why patients are at risk for learning fear at veterinary offices (see Chapter 2). • Learning of adaptive fear at the neurochemical level in the amygdala and the hippocampus is modulated by cortisol levels (see Chapters 4 and 6 and the “Protocol for Teaching Your Dog to Take a Deep Breath and Use Other Biofeedback Methods as Part of Relaxation”). • As cortisol levels increase, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) increases, which allows molecular memory to be made through the creation of new proteins (Peters et al., 2004) (see Fig. 3-5, A and B, in Chapter 3). • This same process is involved in learning how to cope with arousal. • Fear can be almost instantly encoded because the amygdala is “pre-adapted” to respond to perceived threats. However, behaviors associated with learning to cope with arousal cannot be encoded at the molecular level if the cortisol level is too high. • An optimal range of cortisol produces an optimal range of BDNF and cytosolic response element binding protein (CREB). • True complex, associative, and adaptive learning will occur at the molecular level only when CREB and BDNF are within this range. • This is why in situations scary to the patient we see an almost invariant version of avoidance and withdrawal behaviors associated with arousal. Doorways should provide sufficient space that no dog or cat is constrained to come within its personal approach distance of another animal (Fig. 1-3). This distance is 1 to 1.5 body lengths and varies individually with the patient. Large doors with porches or entryways can accomplish such avoidance easily (see Fig. 1-3). Windows, glass doors, and large panels of glass in doors also help. In urban environments, a double set of doors with large panels of glass can help accomplish the goal of avoiding abrupt introductions. Staff can be schooled to help orchestrate safe and non-stressful movement through doors. Fig. 1-3 A panoramic view of a well-designed entryway. A, Two double doors on each side of the reception area. B, A clear and global view of both doors and the waiting area. C, Wide open waiting area on one side of the reception area with plenty of windows. (Thanks to Hickory Veterinary Hospital, Plymouth Meeting, PA, for allowing photography.) Figure 1-3 shows a panoramic view of an entryway that was well designed with the patients’ behavioral concerns in mind. Figure 1-3, A, shows that there are two double doors on each side of the reception area. This design allows dogs to go in one door and out another to avoid meeting each other, if needed. Regardless, everyone can see who is coming and going, so avoidance and orchestration of movement of animals by staff are possible. Figure 1-3, B, shows that the reception staff has a clear and global view of both doors and the waiting area. The high ceilings give the illusion of even more space than the already large floor plan provides, which helps clients who may worry about their dog’s reactions to other dogs. Figure 1-3, C, shows the wide open waiting area on one side of the reception area (note the large number of windows). There is a mirror image of this waiting area on the other side of the reception area, allowing dogs and cats or fractious animals to be separated. Figure 1-3, B and C, also shows that well-placed benches outside increase the amount of waiting area space and may allow many pets and clients to be calmer than they would be inside the hospital. Some exams and procedures may be best done outdoors where the patients can focus on other activities and not feel so entrapped. Anyone who watches patients and clients in a waiting room is aware that few dogs, cats, or humans are comfortable. One study (Hernander, 2008) that examined the role of waiting rooms in creating stress in the waiting room reported a number of conclusions that are important to consider if we are to be successful in creating behavior-centered practices. • Although there was no difference between male and female dogs in the level of stress displayed, dogs accompanied by both a male and a female client were more stressed than dogs accompanied by only one client. • Dogs who had recently been to the clinic had higher stress values than dogs who had not visited recently. This finding has profound implications for the invasive nature of some of the care provided by veterinary staff as perceived by the dogs. • Dogs who stayed in waiting rooms that were not chaotic and had sufficient time to calm were less stressed than dogs who were moved quickly. • Weighing dogs on the scale is much more stressful than sitting in the waiting room. This finding supports the idea that we should teach dogs how to be weighed and design scales and placement of them so that the dogs have some control over their participation in the process. The busier the practice, the more crowded the waiting room can become. Urban veterinary practices may have limited space and should use schedules, exam rooms, and treatment areas sanely so that no patient has to sit in the waiting room with their human hanging onto them for dear life. If the client looks or sounds worried, so is the patient. Action must be taken to decrease patients’ arousal levels immediately. Distressed patients often are calmer waiting in the car than they are in a busy and noisy waiting room. As an alternative, patients who are good with humans but might be afraid of other animals may be accommodated in the reception area through the creative use of barriers. Figure 1-4 shows a reception area with pass-through gates that can be closed, basically changing an open floor plan to one with concentric circles and visual barriers. Having such flexibility can be priceless. Fig. 1-4 Notice the gates on each side of the reception island. These can both be closed to create visual barriers for fearful animals. Also note the lower levels of the desk so that no one has to lean over a patient. Finally, notice that a visual inspection of the exam rooms is possible through the windows in doors. There is little chance of startling any animal if some common sense is used. In busy practices with fractious patients, windows and well-placed mirrors are safety measures. (Thanks to Hickory Veterinary Hospital, Plymouth Meeting, PA, for allowing photography.) We may do well to evaluate the stress level of each animal (and client), note these in the records, and use these to inform our handling procedures that day and to create a plan for reducing stress for handling and veterinary care in the future. The evaluation system used by Hernander (2008) is easy for any practice to implement and is presented in Table 1-3. TABLE 1-3 Rating System for Assigning a “Stress Value” to Dogs in Veterinary Waiting Rooms Adapted from Hernander, 2008. We can expand this scale to address many aspects of veterinary care and intervention. See Box 1-1 for the specific scales found in the separate questionnaire, “Scales to Evaluate Stress Level of Dogs at Veterinary Hospitals.” A version of these scales for client use at the hospital or at home is available as a client handout (“Protocol for Assessing Pain and Stress in Dogs”). Similar questionnaires are available for cats and are discussed in Chapter 5.

Embracing Behavior as a Core Discipline

Creating the Behavior-Centered Practice

Why Care About Behavior?

Evaluating the Patient: How Often Should You See Clients and Their Pets?

Age

Frequency of Veterinary Checks

Behavior Landmarks of Interest

Through 16 weeks

Every 2-3 weeks or more frequently if concerned; consider weekly appointments if client is inexperienced in any manner (i.e., novice pet person, new species, new breed)

Housetraining/use of litterbox, development of appropriate inter-specific play behaviors; leash/car manners (cats, too); social exposure to novel humans and physical exposure to new environments and stimuli

>16 weeks to 1 year

Every 2-4 months

Sexual maturity from ~6-9 months of age; marking behaviors; onset of social maturity can be 9-10 months of age for some dogs

1-2 years

Every 6 months, minimum

Period of social maturity for most cats and dogs; end of social maturity for some dogs can be 18 months; cats may not be fully socially mature until 3-4 years; onset of most behavioral conditions

2-~8 years (depending on breed and size)

At least annually

Behavioral maturity; by 2 years of age, most behavioral conditions are becoming fully developed and will worsen without redress; at about 6 years, evaluate cognition and decide whether to initiate supplements or behavioral diets

≥8 years

At least every 6 months

Behavioral conditions associated with chronic illness or aging; consider supplements, diets, nutraceuticals; rehabilitative and cognitive therapy to keep the patient’s body and mind flexible

≥12 years

At least every 3-4 months; more often if chronic condition identified

Possible cognitive changes associated with aging; may be painful because of degenerative changes; consider household, diet nutraceuticals, supplements, conditioning, accommodations for changes in elimination behaviors/mobility, conveyances (steps into car, slings for stairs, buggies, special bedding or flooring)

Appointment Length and Behavior-Centered Practices

Listening to Clients

Questions to Ask of Clients with New Dogs or Cats That May Elicit Concerns or Gaps in Knowledge

Providing Quality Information at Classes and Appointments

Evaluating “Normal”

What Can We Change?

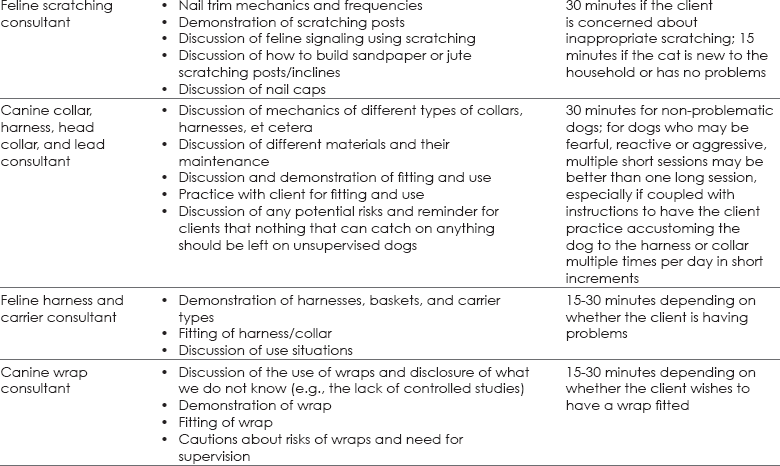

Stress Value

Dog’s Behavior and Appearance

1

Calm, relaxed, seemingly unmoved

2

Alert, but calm and cooperative

3

Tensed, but cooperative, panting slowly, not very relaxed, easily led on lead

4

Obviously very tensed, anxious, shaking, whining, will not sit/lie down, panting intensely, difficult to maneuver on lead

5

Extremely stressed, barking/howling, tries to hide, needs to be lifted up or to be firmly forced when pulled by the lead (please do not do this)