6 Electrolyte and Acid-Base Disorders

Serum Potassium Concentration

Causes of Hypokalemia

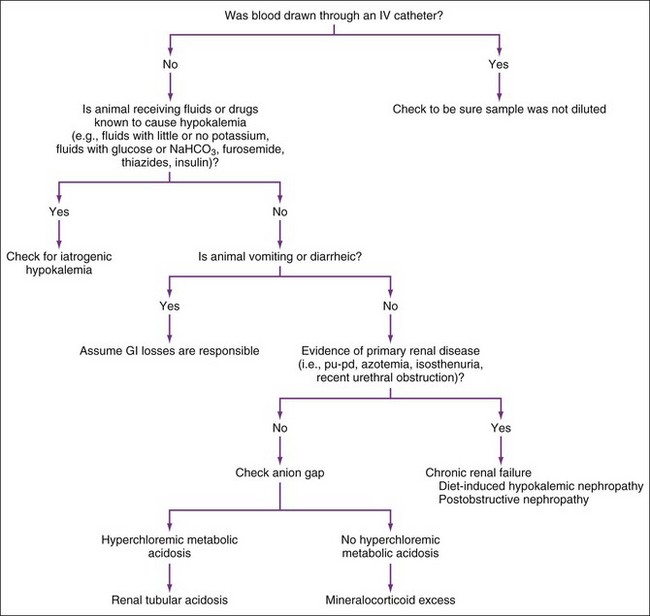

The three possible mechanisms for hypokalemia are (1) decreased intake, (2) translocation of potassium from extracellular to intracellular fluid, and (3) loss via the kidneys or gastrointestinal tract (Box 6-1 and Figure 6-1). Dilution of serum potassium concentration by giving potassium-free fluids, especially those containing glucose, may contribute to hypokalemia. Decreased intake may aggravate hypokalemia caused by increased loss or translocation, but it is unlikely to cause hypokalemia by itself. Hypokalemia often results from a combination of decreased intake plus urinary or gastrointestinal losses (e.g., administering potassium-free fluids to anorexic animals).

Box 6-1

Causes of Hypokalemia

Pseudohypokalemia (infrequent and rarely causing significant change)

Increased Loss (most common and important category)

Vomiting of gastric contents (common and important)

Diarrhea (common and important)

Chronic renal failure in cats (common and important)

Diet-induced hypokalemic nephropathy in cats (important)

Postobstructive diuresis (common and important)

Diuresis caused by diabetes mellitus/ketoacidosis (common and important)

Loop diuretics (e.g., furosemide) (common and important)

Thiazide diuretics (e.g., chlorothiazide, hydrochlorothiazide)

Proximal (type II) RTA after NaHCO3 treatment (rare)

Mineralocorticoid excess (rare)

Hyperadrenocorticism (mild changes)

Primary hyperaldosteronism (i.e., adenoma, hyperplasia)

Translocation (Extracellular Fluid → Intracellular Fluid)

Glucose-containing fluids ± insulin (common and important)

Total parenteral nutrition solutions (uncommon, but important)

Hypokalemic periodic paralysis (Burmese cats) (rare)

Decreased Intake (Unlikely to cause hypokalemia by itself unless diet is severely deficient)

Administration of potassium-free fluids (e.g., 0.9% NaCl, 5% dextrose in water)

FEk, Fractional excretion of potassium; RTA, renal tubular acidosis.

Modified from DiBartola SP: Fluid therapy in small animal practice, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2000, WB Saunders, p 93.

Causes of Hyperkalemia

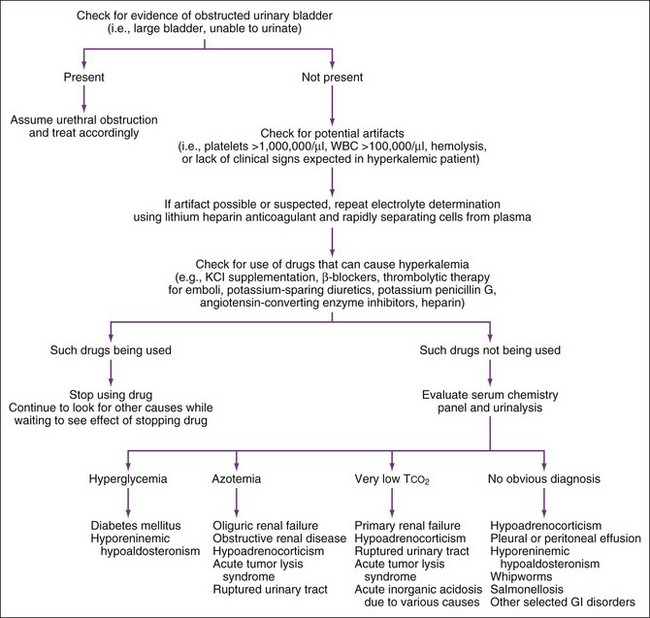

The three mechanisms for hyperkalemia are (1) increased potassium intake, (2) translocation of potassium from intracellular to extracellular fluid, and (3) decreased urinary potassium excretion (most common) (Box 6-2 and Figure 6-2). Increased intake is seldom the cause, unless potassium administration is greatly excessive or concurrent renal or adrenal impairment exists.

Box 6-2

Causes of Hyperkalemia

Pseudohyperkalemia

Thrombocytosis (usually mild, but can produce marked changes)

WBCs > 100,000/µl (rare cause, but can cause significant changes)

Decreased Urinary Excretion (most common)

Urethral obstruction (common and important)

Ruptured bladder/ureter (uncommon but important)

Anuric or oliguric renal failure (common and important)

Hypoadrenocorticism (uncommon but important)

Selected gastrointestinal diseases (e.g., trichuriasis, salmonellosis, perforated duodenal ulcer)

Chylothorax with repeated pleural fluid drainage (rare)

Hyporeninemic hypoaldosteronism (with diabetes mellitus or renal failure) (rare)

Drugs (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors [e.g., enalapril],* potassium-sparing diuretics [e.g., spironolactone, amiloride, triamterene],* prostaglandin inhibitors,* heparin*)

Translocation (Intracellular Fluid → Extracellular Fluid)

Insulin deficiency (e.g., diabetic ketoacidosis) (uncommon and transient)

Acute inorganic acidosis (e.g., HCl, NH4Cl) (rare)

Hyperkalemic periodic paralysis (rare)

Drugs (nonspecific beta blockers [e.g., propranolol*])

IV, Intravenous; RBC, red blood cell; WBC, white blood cell;.

Modified from DiBartola SP: Fluid therapy in small animal practice, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2000, WB Saunders, p 100.

Decreased excretion is the most important mechanism; hyperkalemia seldom occurs if renal function is normal. The most common causes of decreased urinary potassium excretion are urethral obstruction, ruptured bladder (or ureter), anuric or oliguric renal failure, and hypoadrenocorticism. Hyperkalemia may occur within 48 hours of feline urethral obstruction, but it does not usually occur for at least 48 hours after urinary bladder rupture. Hyperkalemia seldom occurs in chronic renal failure and then usually only in oliguric patients. Hyperkalemia, hyponatremia, and Na/K ratios less than 27 : 1 are often (but not always) found in animals with hypoadrenocorticism or renal failure. An adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation test (see Chapter 8) is necessary to diagnose hypoadrenocorticism, because identical electrolyte abnormalities can occur because of oliguric renal failure, whipworms, salmonellosis, and pleural or peritoneal effusions.

The most important causes of serious hyperkalemia (i.e., > 6.0 mEq/L) are oliguric and anuric acute renal failure (e.g., ethylene glycol ingestion), urethral obstruction in male cats, and hypoadrenocorticism. Pseudohyperkalemia should be eliminated first. If serum potassium concentration is greater than 7.0 mEq/L and the patient is asymptomatic (e.g., normal electrocardiogram and physical examination), serum potassium concentration should be rechecked using lithium heparin plasma. After artifact has been eliminated, history should be examined for iatrogenic causes. If hyperkalemia might be iatrogenic, the drug in question should be discontinued and serum potassium rechecked in 1 to 2 days. Diagnostic evaluation should continue in case another disease is present, however. Hyperkalemia is usually an indication for evaluation of some or all of the following: serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), urinalysis, and a resting serum cortisol concentration (see Chapter 8).

Urinary Fractional Excretion Of Potassium

Serum Sodium Concentration

Causes of Hyponatremia

Accurate evaluation of hyponatremia requires measuring plasma osmolality. Most hyponatremic patients are hypoosmolar, but hyperglycemia (i.e., diabetes mellitus) or mannitol administration (Box 6-3) may cause hyponatremia with hyperosmolality. The next step in evaluating hyponatremia is to estimate hydration status. History may indicate fluid loss. Physical examination allows some evaluation of a patient’s hydration status (e.g., skin turgor, moistness of mucous membranes, capillary refill time, pulse rate and character, appearance of jugular veins, presence or absence of ascites).

Box 6-3

Causes of Hyponatremia

With Low Plasma Osmolality

Overhydration (i.e., hypervolemia)

Severe hepatic disease causing ascites (common)

Congestive heart failure causing effusion (common)

Nephrotic syndrome causing effusion (common)

Advanced renal failure (primarily oliguric or anuric)

Dehydration (i.e., Hypovolemia)

Gastrointestinal loss (common) (i.e., vomiting or diarrhea)

Hypoadrenocorticism (uncommon but important)

Normal Hydration (i.e., Normovolemia)

Inappropriate fluid therapy with 5% dextrose, 0.45% saline solution, or hypotonic fluids (important)

Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) (rare)

Modified from DiBartola SP: Fluid therapy in small animal practice, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2000, WB Saunders, p 60.

Normovolemic hyponatremia may be caused by primary (i.e., psychogenic) polydipsia, fluid therapy (e.g., 5% dextrose or 0.45% saline), SIADH (rare), drugs with antidiuretic effects, and myxedema coma from hypothyroidism (rare). Primary polydipsia (see Chapter 7) usually occurs in large breeds of dogs. These dogs have severe polydipsia, polyuria, severe hyposthenuria, mild hyponatremia, and mild plasma hypo-osmolality. SIADH refers to excessive antidiuretic hormone (ADH) release despite lack of normal stimuli; it can be caused by malignancy, pulmonary disease, or central nervous system (CNS) disorders. Diagnosis of SIADH requires eliminating adrenal, renal, cardiac, and hepatic disease and finding inappropriately high urine osmolality (> 100 mOsm/kg) despite serum hypo-osmolality. Drugs that stimulate ADH release or potentiate its renal effects may lead to hyponatremia with normovolemia.

The most common causes of moderate to marked hyponatremia (i.e., Na <135 mEq/L) in dogs and cats include vomiting, hypoadrenocorticism, and advanced congestive heart failure (with or without concomitant diuretic therapy). History or physical examination usually reveals the cause, but a resting serum cortisol should be measured (see Chapter 8) if the clinician suspects hypoadrenocorticism. If the cause is still unknown, plasma osmolality measurements are recommended.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree