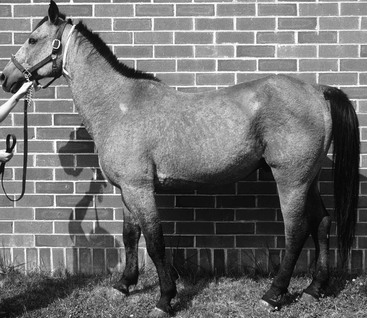

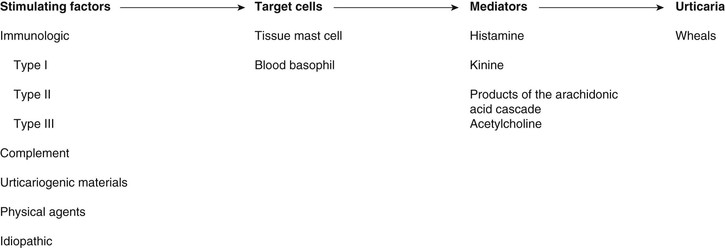

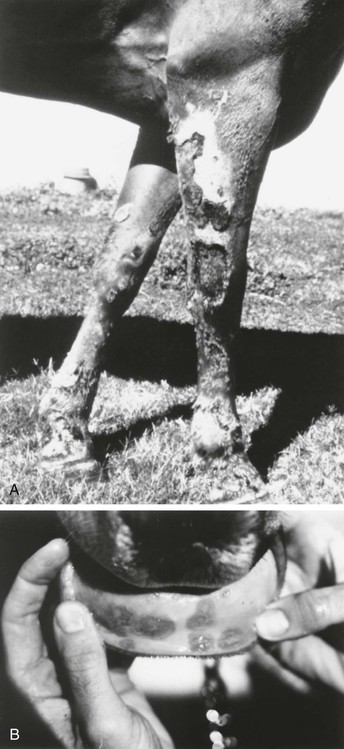

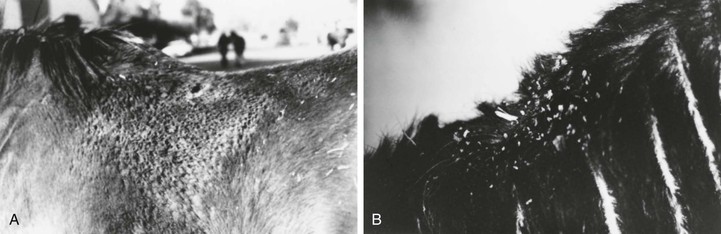

Stephen D. White *, Consulting Editor Stephen D. White The term pemphigus is derived from the Greek word for “blister” and is used to describe a group of autoimmune vesiculobullous disorders characterized histologically by intraepidermal acantholysis and immunologically by intercellular deposition of immunoglobulin. Pemphigus foliaceus is the most common of this group of autoimmune diseases; in large animals it has been reported in horses,1,2 goats,3,4 and a donkey.5 In small animals, pemphigus foliaceus has been putatively associated with drugs,6 but this has not been identified in large animals. The factors precipitating the development of pemphigus foliaceus in large animals are unknown. The clinical lesions recognized in horses and goats are primarily scaling and crusting. Pemphigus foliaceus is characterized by the production of autoantibodies. In humans and dogs, these are directed against transmembrane proteins (desmoglein 1 in humans and a minority of dogs, desmocollin-1 in most dogs6a). The pemphigus autoantibody binds to the transmembrane protein, resulting in release or activation of one or more proteolytic enzymes. These enzymes destroy the attachments between adjoining epidermal cells. The result is acantholysis; the epidermal cells assume a rounded shape and separate from one another, leading to the formation of intraepidermal clefts and vesicles.7 Pemphigus foliaceus is characterized clinically as a generalized exfoliative dermatitis (Fig. 40-1, Color Plate 40-1). Ventral or peripheral limb edema and crusts are the most common clinical signs.1 In one study, no age, breed, or gender predilection was noted, although 80% of affected horses first exhibited signs between September and February.1 In the horse, lesions are usually first noted on the head, limbs, or ventrum. Initial lesions also may be associated with fever, depression, or rarely urticaria. The disease usually progresses to involve the entire body over days to weeks. The primary lesion is a pustule, but these are fragile and transient lesions. Pustules rupture soon after formation, resulting in erosions, epidermal collarettes (rings of exfoliating superficial epidermis), scale, and crust. The lesions may or may not be associated with pruritus or pain.1,2 In the goat, pemphigus foliaceus also presents as a generalized exfoliative dermatitis. In the limited number of cases described, lesions were initially noted on the limbs, perineal region, and ventrum. The lesions consisted of crusting and scaling resulting from rupture of vesicles and bullae. Pruritus and malaise appear to be variable findings.3 Diagnosis of pemphigus foliaceus in large animals is typically based on biopsy of lesions submitted for routine histopathology. Characteristic histologic findings include intragranular to subcorneal cleft and vesicle formation associated with acantholysis. Both follicular and surface epithelia are frequently involved. Neutrophils tend to predominate in the inflammatory infiltrate, although eosinophils may also be present.1–3 Because certain strains of Trichophyton species of dermatophytes may also cause acantholysis, any histology suggestive of pemphigus foliaceus must be stained for fungi.8 Direct immunofluorescence or immunohistochemistry as an aid in the diagnosis of pemphigus foliaceus in horses and goats has also been reported but is somewhat limited to research and academic institutions.3,7,9 Indirect immunofluorescence testing (for pemphigus antibodies in serum) is reported to be unreliable for the diagnosis of pemphigus foliaceus in horses, although this may be due to variability in the substrate used.7,10 Treatment is corticosteroids at immunosuppressive doses, such as prednisolone at 1 mg/kg orally (PO) every 24 hours (q24h) or dexamethasone at 0.08 to 0.1 mg/kg PO q24h, then tapering. Oral prednisolone is preferred to prednisone because some horses are unable to metabolize prednisone into the active metabolite of prednisolone.11 Injectable gold (Solganal [Schering]) was also used successfully, but this product is no longer available. There are anecdotal reports of benefits using another gold salt, aurothiomalate (Myochrysine [Sanofi Aventis]), 1 mg/kg intramuscularly (IM) every 7 days. Gold salts take 1 to 3 months to reach effectiveness, when dosage frequency can be tapered to every 14 to 30 days. Adverse reactions of gold salts, although rare in the horse, include thrombocytopenia and glomerulonephropathy. There are also reports of azathioprine (1 to 3 mg/kg PO q24-48h) being used for various autoimmune skin diseases in horses.12,13 A potential side effect is thrombocytopenia because horses have low levels of the enzyme thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT),14 which is responsible for the metabolization of azathioprine in other species, including humans. However, the author has administered azathioprine (1 to 3 mg/kg PO for 1 month, then q48h) to 8 healthy horses with no deleterious effects.15 Azathioprine is used as a steroid-sparing drug with corticosteroids, eventually to decrease the steroid needed. Approximate cost in a 500-kg horse for daily azathioprine is $300/month. Goats have also been treated successfully with corticosteroids (dexamethasone, prednisolone) and aurothioglucose.3,4,9 Dosages approximate those for the horse. The response to treatment in equine pemphigus foliaceus varies from patient to patient. Many horses require lifelong administration of medication to control the clinical signs; others may be gradually weaned from medication without further relapse. In one study where follow-up information was available for 13 horses, 4 were euthanized because of complications from the disease or its treatment. The reported cases of caprine pemphigus foliaceus are insufficient in number to establish a reliable prognosis. Pemphigus vulgaris is a rare autoimmune skin disease anecdotally reported7 in horses and recently definitively diagnosed in a Welsh pony.16 In that report, the diagnosis was confirmed with both direct and indirect immunofluorescence and immunoprecipitation studies, the latter identifying circulating immunoglobulin (Ig)G directed against the epidermal transmembrane protein desmoglein 3, similar to the pathogenesis in humans and dogs. Clinical signs are vesicles and ulcerations seen in mucocutaneous and cutaneous areas. Initial corticosteroid treatment improved the clinical signs, but onset of laminitis necessitated a dose decrease with a recurrence of lesions and development of oral ulcers. Despite successive adjunctive treatment with azathioprine, gold salts, and dapsone, the disease progressed and the pony was euthanized. Necropsy showed additional lesions of the cardia of the stomach.16 Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune vesiculobullous and ulcerative disorder that affects the cutaneous basement membrane zone (BMZ). It has been rarely noted in horses.7,17 Initiating triggers for the disease in the horse are unknown. The pathophysiology of bullous pemphigoid in horses is assumed to be similar to that described in other mammals. Complement-activating anti-BMZ antibodies bind to a glycoprotein antigen in the lamina lucida of the BMZ. In horses, this has been shown to be bullous pemphigoid antigen II (also called collagen XVII). Complement activation results in degranulation of mast cells and chemotaxis of neutrophils and eosinophils. Eosinophils release tissue-destructive enzymes with resultant injury to the BMZ, loss of dermoepidermal adherence, and subsequent blister formation.7 Equine bullous pemphigoid is characterized clinically by painful, crusted, or ulcerative lesions of the skin (face and axillae), mucous membranes, and mucocutaneous junctions. Bullae are rare.7,16 Ulceration may involve the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The diagnosis is based on histopathologic and, when available, immunofluorescent findings. Treatment is the same as for pemphigus foliaceus; the few cases reported have not had favorable outcomes, but the author has seen a case that initially responded well to corticosteroids. Alopecia areata is a disease of horses and cattle typified by areas of nonpruritic alopecia.7,18,19 One horse has been described with severe hoof dystrophy on all four legs.20 In one report, the median age was 9 years, with an age range from 3 to 15 years. Alopecia was the primary dermatological abnormality in all horses and most commonly affected the mane, tail and face, although any part of the body could be affected (Color Plate 40-2).21 Histologically, a lymphocytic infiltrate surrounding the base of the hair follicle is seen, but in long-standing cases this infiltrate may not be present.22 A mare with a T-cell lymphocytic infiltrate causing a mural folliculitis of the isthmus (central section) of the hair follicles was described.22 Antibodies targeting the hair follicle itself have been documented.23 Most horses regrow the hair, but this may take up to 2 to 3 years, and the disease may wax and wane, worsening most commonly in the spring and summer months.21 Corticosteroids may hasten hair regrowth. Mane and tail “dystrophy” of Appaloosas and other breeds may in fact be a form of alopecia areata. Because of the circular nature of the alopecia, this disease is often mistaken for ringworm. Stephen D. White Atopic dermatitis can be defined as an abnormal immunologic response to environmental allergens like pollens, barn dust, and molds. It is increasingly being recognized as a cause of pruritus in horses. The disease may be seasonal or nonseasonal, depending on the allergen(s) involved. Age, breed, and gender predilections have not been extensively reported. A familial predisposition may be present.1 The presumed etiology is a type I (immediate) hypersensitivity response mediated by IgE. Evidence indicates that atopic horses do produce allergen-specific IgE2,3; the IgE is presumed to be directed against specific allergens. When that allergen is bound to two or more IgE antibodies on the surface of a mast cell, the mast cell releases granules containing various substances that cause erythema, vascular leaking, and pruritus. Pruritus, often affecting the face, distal legs, or trunk, is the most common clinical sign. Alopecia, erythema, urticaria, and papules may all be present. Urticarial lesions may be severe but nonpruritic. In one study of 54 horses with atopic dermatitis, 28 horses had urticaria, 8 had pruritus, and 18 had both.3 Horses may have a secondary pyoderma typified by excess scaling, small epidermal collarettes, or encrusted papules (miliary dermatitis). Diagnosis of atopic dermatitis is based on clinical signs and exclusion of other diagnoses, especially parasite (Culicoides) allergy. Diagnosis is based on clinical signs and exclusion of other pruritic skin disease. Confirmation to formulate allergen-specific immunotherapy (ASIT [hyposensitization]) is based on either intradermal testing (IDT) or serum allergy tests. IDT involves a series of intradermal injections of aqueous allergen extracts along with a positive (histamine) and negative (saline) control. Injections are usually performed over the lateral cervical or thoracic region, and the sites are then observed for 30 minutes to 24 to 48 hours for evidence of wheal formation. A positive reaction does not necessarily mean that the horse’s clinical signs are caused by the reacting allergen, but rather that the horse has antibodies to the allergen that, on intradermal exposure, cause wheals to form. False-negative IDT reactions may occur, the most important cause of which is the use of corticosteroids, antihistamines, or phenothiazine tranquilizers before testing, especially within the previous 14 days.3a Horses with atopic dermatitis generally have a higher incidence of positive reactions than healthy horses, but the diagnosis (as in other species) cannot be solely made on the basis of the IDT or serologic test alone. Such tests should be interpreted in light of the history of the disease. For example, a horse with seasonal signs is more likely to have an allergic response to seasonal allergens (pollens in summer, barn dust in winter). This interpretation will help the clinician determine which allergens might be relevant in hyposensitization, should the owners choose that treatment.2–6 IDT and available serologic tests look for allergen-specific IgE in the animal’s blood,7 but their use on horses and other domestic species is not without controversy. A recent study showed no statistical difference in the efficacy of hyposensitization between horses tested with IDT and those tested with serology.3 Preferentially, IDT and/or serologic testing are performed on horses with atopic dermatitis that have owners interested in pursuing hyposensitization. It should be remembered that in regard to food allergy, neither serologic testing nor IDT likely has any relation to reality. Clinical research is ongoing to determine the most important allergens, their testing dilutions, and effective control substances.8,9 Corticosteroid treatment is usually effective in the control of pruritus or urticaria due to atopic dermatitis. The usual oral medication used is prednisolone (1 mg/kg PO q24h), although dexamethasone (0.05 mg/kg PO q24h) can also be used. The injectable dexamethasone solution may be used orally, although the clinician should remember that the bioavailability is 60% to 70% of the injectable route. Corticosteroids in horses may cause various adverse effects, including steroid hepatopathy, laminitis, and iatrogenic hyperadrenocorticism. Therefore, other modalities of treatment may be used, such as the antihistamines hydroxyzine pamoate (200 to 400 mg/500 kg PO q12h) or cetirizine (0.2 mg/kg PO q12h); doxepin, a tricyclic antidepressant with antihistaminic effects (300 to 600 mg/500 kg PO q12h); or diethylcarbamazine syrup (6 to 12 mg/kg PO q24h). Hydroxyzine, cetirizine, and doxepin may cause either drowsiness or nervousness, although these adverse effects are uncommon. Cetirizine is very expensive, and since it is the active metabolite of hydroxyzine, if the latter is ineffective in an individual horse, the cetirizine probably will be as well. Pyrilamine maleate, though often used in the horse, in fact has poor oral bioavailability.10 Some clinicians have noted improvement when an essential fatty acid (EFA) product is added to the feed. Platinum Performance (Platinum Performance Inc., Buellton, Calif. [Dr. W. Rosenkrantz, personal communication, 2004]) has been used successfully in some atopic horses as an adjunctive treatment. In general, hyposensitization injections for any manifestation of atopic dermatitis in the horse should be evaluated for efficacy for at least 12 months. The veterinarian should maintain consistent communication with the client to monitor the progress of treatment and encourage the owner to continue with the injections for the full year. Although most horses will need to be maintained on injections for life, if hyposensitization is successful, perhaps as high as 25% may be able to discontinue the treatment without recurrence.3 Experience at the University of California, Davis, School of Veterinary Medicine (UCD-SVM) shows that about 65% to 70% of atopic horses improve with hyposensitization3,11; other researchers have reported even better results but in a noncontrolled study.12 Urticaria is characterized by transient focal swellings in the skin or mucous membranes called wheals, which represent localized areas of dermal edema. Angioedema is essentially identical but involves the subcutaneous tissues. The swelling of angioedema is diffuse, often involving the entire face and neck of the animal. Urticaria is more frequently recognized in the horse than in ruminants. Allergic urticaria is usually caused by atopic dermatitis (environmental allergens like pollens),1,5,6,13, drug eruptions (especially antibiotics14 and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]), contact allergies, and food allergies (rarely).15 Physical urticarias are less common and involve a nonimmunologic pathogenesis. The three most important categories include mechanically induced, such as dermatographism, essentially a “pressure” urticaria; cold urticaria; and exercise-induced urticaria. Miscellaneous diseases that can cause urticaria include dermatophytosis (initial lesions),16 pemphigus foliaceus, “stress” (sometimes seen in racehorses immediately before a race), and vasculitis (Box 40-1). Urticaria is a recognized manifestation of milk allergy in cattle.17 The wheals result from vasodilation and transudation of fluid from capillaries and small blood vessels. Both immunologic and nonimmunologic factors can trigger release of mediators from mast cells and blood basophils that will ultimately produce the characteristic wheals (Fig. 40-2). The most frequently cited immunologic mechanism of urticaria is type I hypersensitivity (IgE). Non–IgE-dependent, immune-mediated urticaria may be induced by either type II (cytotoxic, involving antibody and complement) or type III (immune complex) hypersensitivity reactions. Complement-activated urticaria may involve either immunologic or nonimmunologic mechanisms and may occur through either the classic or the alternative pathway. Urticariogenic materials can induce wheal formation without involving immunologic mechanisms by being ingested, injected, or contacting the animal. Physical agents, including mechanical injury, thermal changes, and solar radiation, may induce urticaria. An example of mechanically induced urticaria is dermatographism (whealing after blunt scratch injury to the skin). Local or generalized exposure to heat or cold may induce urticarial lesions in certain individuals. Wheals range from 1 to 10 cm (0.4 to 4 inches) in diameter and tend to involve the cervical and craniolateral thorax (Fig. 40-3). The animal may or may not be pruritic. Alopecia is not usually a feature of urticaria. The most important factor in distinguishing urticaria from other nodular diseases is that the individual lesions pit with pressure. This is easily demonstrated in the early stages of wheal formation, when the lesions consist primarily of dermal edema. In the later stages, when there is cellular infiltration into the dermis, the pitting is less apparent. Urticaria is usually a clinical diagnosis; the diagnostic dilemma is to determine the cause of the urticarial eruption. A skin biopsy not only will lend support to the clinical diagnosis of urticaria but also may show evidence of pemphigus foliaceus, dermatophytosis, or vasculitis. Initiation of ectoparasite control, IDT or serologic tests for atopic dermatitis, fungal culture, skin biopsy, and/or feed trials may all be used to determine the underlying disease.13 Avoiding the allergen/initiating factor or treating the underlying disease is the best therapy. When this is not possible or when the allergens cannot be identified, medical therapy should be used, as described under Atopic Dermatitis. The principal cutaneous manifestation of milk allergy is urticaria and is usually seen in cows during the drying-off period. Increased intramammary pressure presumably causes milk proteins to gain access to the circulation, where they induce a type I hypersensitivity reaction.18 The disorder is believed to be hereditary and familial, with cattle of the Channel Island breeds demonstrating increased susceptibility. The urticarial reaction can be localized or generalized. Other clinical signs that may be noted include muscle tremors, respiratory distress, restlessness, ataxia, dullness, and even maniacal behavior. Diagnosis is made by observing an edematous swelling at the site of an intradermal injection of the cow’s milk or the milk protein casein diluted 1 : 1000, in combination with the appropriate clinical signs.18,19 Treatment involves the use of antihistamines early in the course of the disease. Prevention requires avoiding milk retention. An affected cow is likely to suffer recurrences of milk allergy, so culling is usually recommended. Erythema multiforme (EM) has been recognized clinically in the horse and in one bull (Fig. 40-4). This is an immunologic reaction in the skin, and programmed keratinocyte cell death (apoptosis) is the prominent change seen on biopsy. The keratinocytes may be killed specifically by killer lymphocytes. The many possible etiologic factors include infectious diseases, drugs, systemic disease, and neoplasia. In the horse, drugs are probably the most frequent inducers of EM, although in many cases an underlying disease is undiagnosed.20,21 In one bull the EM may have been caused by a pyelonephritis found on necropsy.22 Clinical lesions are characterized by macules, papules, urticarial lesions, or vesicular bullous lesions. Individual lesions may expand peripherally, leading to formation of target-like lesions. Scaling and crusting are usually not a feature of equine EM unless the disease is characterized by erosions or ulcers. Individual lesions can persist for several days, unlike urticarial lesions. Pruritus and pain are variable but not usually seen. Lesions may occur in association with or after an infection or drug administration. The late Dr. A.A. Stannard of UCD-SVM had theorized that reticulated and hyperesthetic leukotrichia may also represent a type of EM in the horse.21 A recent report associated EM in a horse with equid herpesvirus 5.23 Interestingly, a similar disease, toxic epidermal necrolysis, has rarely been reported in cattle.24 Differential diagnoses include urticaria, amyloidosis, and other nodular papular diseases. The diagnosis is made on history, physical examination, and skin biopsies. Histologic changes are distinctive and often include a lichenoid pattern with keratinocyte apoptosis. Vesicular lesions may be present and can include more confluent areas of keratinocyte destruction with massive spongiosis and subepidermal and intraepidermal edema. Treatment should be directed toward the underlying cause if one can be found. A drug eruption should be high on the list, and searching the history for recent drug administration is important. Although some cases of EM are self-limiting and may resolve within 1 to 3 months,20 corticosteroid treatment as for pemphigus foliaceus may be tried. In our experience, reticulated leukotrichia does not resolve spontaneously and does not respond to corticosteroids. Vasculitis is a histopathologic term that implies the presence of inflammatory changes in the walls of blood vessels, and it is associated with a broad spectrum of disorders. Cutaneous vasculitis is recognized in horses and is most often seen as a feature of photoaggravated dermatitis, drug reactions, or purpura hemorrhagica.25 Mules and donkeys may also be affected.25Affected vessels may be limited to the skin or may involve other organs, resulting in systemic disease. The cutaneous lesions are characterized by crusts, scales, edema, purpura, necrosis, and ulceration, most often affecting the legs (Fig. 40-5, Color Plate 40-3). As a clinical entity, photoaggravated vasculitis seems to be more common (if poorly understood) in California and the western United States. Although previously termed leukocytoclastic vasculitis, the most common histologic finding is cell-poor and lymphocytic/histiocytic vasculitis.25 It generally affects mature horses and produces lesions confined to the lower extremities that lack pigment, although pigmented legs may also be affected. Lesions are multiple and well demarcated, with the medial and lateral aspects of the pastern the most common sites. Initially, erythema, exudation, crusting, erosions, and ulcerations develop, followed by edema of the affected limb(s). Some lesions may have a “punched-out” appearance. Chronic cases may develop a rough or “warty” surface. Pathogenesis is uncertain; an immune complex etiology has been suggested, and when lesions are restricted to nonpigmented areas this suggests a role for ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Drug reactions may be a potential cause.21 One report also implicated Staphylococcus intermedius.26 It must be emphasized that cutaneous vasculitis can occur anywhere on the body and may become generalized. The differential diagnosis is photosensitization, particularly that caused by contact. The diagnosis is confirmed by skin biopsy, which demonstrates vasculitis, often with vessel wall necrosis and thrombosis involving the small vessels in the superficial dermis. These changes may be difficult to demonstrate. Treatment involves corticosteroids at relatively high doses (prednisolone at 1 mg/kg PO q12h or dexamethasone at 0.08 to 0.2 mg/kg PO q24h) for 2 weeks, then tapered over the next 4 to 6 weeks. Reducing UV light exposure is helpful, either by bandaging affected legs or stabling inside during daylight hours, or both. In some cases, topical corticosteroids (e.g., betamethasone valerate cream 0.1% or triamcinolone spray 0.015%) may enable the horse to be weaned off systemic corticosteroids. Pentoxifylline (8 to 10 mg/kg PO q12h) may be an effective adjunct treatment. Another alternative (but more expensive) is 0.1% tacrolimus ointment q24h (Protopic [Astellas Pharma US]). This disease recurs in approximately 25% of cases.25 These horses are prone to secondary bacterial infections, and a month of antibiotic treatment (usually trimethoprim-sulfa) is often indicated if the horse has fever or its legs are extensively swollen. Cutaneous vasculitis seemingly is rare in ruminants; one report in calves describes lesions on the forelegs and ear tips occurring within a month on one farm. Histology showed a fibrinous-necrotic or leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Glucocorticoid (prednisolone) therapy was effective.27 A recent article describes systemic vasculitis (polyarteritis nodosa) in four flocks of sheep. Clinical and histologic signs involved several organ systems, including the skin.28 Vasculitis and purpura hemorrhagica are discussed in more detail in Chapter 37. A drug eruption is a cutaneous reaction to any agent that enters the circulation by ingestion, injection, inhalation, or percutaneous absorption. Drug eruptions may or may not be associated with systemic signs. Many drug eruptions are thought to be immunologically mediated hypersensitivity reactions, although on occasion they may occur with the initial administration of a drug and therefore without any prior sensitizing exposure, characteristic of an immunologic reaction. Drug eruptions may also occur after years of repeated asymptomatic exposure to a drug, although this is probably less common than formerly supposed. Any medication can cause a drug eruption, but the compounds most frequently incriminated include antibacterial agents (especially semisynthetic penicillins and the sulfas), phenothiazine tranquilizers, NSAIDs and antipyretics (especially phenylbutazone), local anesthetics, and anticonvulsants. In general, the more recently a drug has been given, the more likely it may be the cause of a skin disease. The clinician should try to determine a temporal association between administration of the drug and the skin disease. Because drug eruptions can result in a wide variety of cutaneous manifestations, they must be considered in the differential diagnosis of all skin disorders. Certain clinical symptoms are more often associated with drug eruptions. Urticaria and angioedema, diffuse erythema, papular rashes, intense pruritus that is poorly responsive to corticosteroids (Fig. 40-6), sharply demarcated ulcers secondary to vasculitides, vesicular and bullous eruptions, and photosensitization should arouse clinical suspicion of a drug eruption. Typically, cutaneous lesions are noted 24 to 48 hours after drug administration, although there may be a longer lag interval. The eruption usually subsides within 24 to 48 hours after exposure ceases, although lesions may persist up to 6 months after the offending agent is eliminated.21 A diagnosis of drug eruption is based on clinical suspicion associated with an incriminating history of drug administration and by ruling out other possible causes. In a suspected case, all medications should be discontinued. If lifesaving medications are being administered, a chemically unrelated compound with similar pharmacologic effects should be substituted. Administration of corticosteroids may provide some relief, but drug eruptions are variably responsive to corticosteroids. Although development of a cutaneous reaction after readministration of the suspected agent would support a diagnosis of drug eruption, readministration is not advisable because it can be fatal. Future exposure to any implicated compounds and chemically related substances should be avoided. Contact dermatitis is recognized in both horses and ruminants and can be subdivided into irritant and allergic contact dermatitis. Irritant contact dermatitis occurs more often and is defined as a cutaneous reaction to an irritating concentration of an offending agent. The substance chemically damages the skin without immunologic mediation. The reaction may occur after a single contact with a strong irritant or after repeated contacts with a milder irritant. Allergic contact dermatitis represents a cutaneous reaction in a sensitized animal to a nonirritating concentration of the offending agent. Tissue damage is immunologically mediated by delayed-type hypersensitivity (type IV), so prior exposure is required to sensitize the skin to the material eliciting the dermatitis.15,17 It may be difficult to differentiate between the two types of contact dermatitis, and it may not be clinically important. In our experience, the vast majority of contact dermatitis cases are iatrogenic, caused by topical products placed on the skin by veterinarians or owners. The clinical lesions associated with allergic and irritant contact dermatitis are very similar. Predisposed areas include the muzzle, extremities, and areas contacted by tack. Early lesions include erythema, edema, and vesiculation that progress to erosions, ulcerations, and crusting and ultimately to lichenification and hyperpigmentation. A gravity-induced drip pattern may be evident when the irritant is a liquid.29 A detailed history is very important—the bedding, all topical products and blankets, and other potential environmental antigens/irritants should be noted. Certain woods release various irritant oils and have been implicated when incorporated into the bedding.30 Patch testing is possible but usually impractical. Provocative exposure is the most useful test for diagnosis of contact dermatitis, although it does not reliably distinguish between allergic and irritant contact dermatitis. It requires avoiding contact with all suspected agents for 7 to 10 days to permit clearing of the skin lesions. The patient is then reexposed to these agents on an individual basis at 7- to 10-day intervals while being observed for recurrence of the dermatitis. When a positive reaction is observed, challenge with the suspected agent should be repeated to confirm the diagnosis. The process is time-consuming, requiring owner patience and cooperation. An animal with a suspected or confirmed diagnosis of acute or irritant contact dermatitis should be placed in an environment where there is negligible chance of exposure to agents that might have produced the dermatitis. Symptomatic treatment pending spontaneous resolution includes gently washing the affected regions with water. Pentoxifylline at the dose noted earlier for vasculitis may be helpful in horses. Stephen D. White Dermatophilosis is caused by an actinomycete bacterium, Dermatophilus congolensis. The organism is a gram-positive, non–acid-fast, branching, filamentous, aerobic bacteria that divides longitudinally and then transversely to form parallel rows of coccoid zoospores. Dermatophilosis affects horses, cattle, sheep, and goats, as well as a wide range of other mammals.1–4 Three conditions must be present for Dermatophilus to manifest: a carrier animal, moisture, and skin abrasions. Chronically affected animals are the primary source of infection, but they become a serious source of infection only when their lesions are moistened, which results in release of zoospores, the infective stage of the organism. Mechanical transmission of the disease occurs by both biting and nonbiting flies, ticks, and possibly fomites. Because normal healthy skin is impervious to infection with D. congolensis, some predisposing factor that results in decreased resistance of the skin is necessary for infection to occur, especially prolonged skin wetting by rain. The organism has been isolated from the environment of affected animals. Distribution is worldwide, but frequency of occurrence of dermatophilosis varies with geographic location; areas with increased rainfall are predisposed. There is no apparent age, breed, or gender predilection. Dermatophilosis is usually seen during the fall and winter months, with the dorsal surface of the animal most often affected (Fig. 40-7, Color Plates 40-4 and 40-5). In horses, this association with the wetter months of the year has led to the term rain scald. Occasionally the lesions involve the lower extremities when animals are kept in wet pastures (“dew poisoning”) or if horses are left in the stall while the stall is cleaned with high-pressure water hoses. In the early stages of disease, the lesions can be felt more easily than they can be seen. Thick crusts can be palpated under the hair coat. Removing the crusts and attached hair exposes a pink, moist skin surface, with both the removed hair and exposed skin assuming a paintbrush shape. The undersurface of the crusts are usually concave, with the roots of the hairs protruding. In cattle and goats, the older term cutaneous streptothricosis is sometimes still used. In sheep the condition is referred to as “lumpy wool” or “mycotic dermatitis” when wooled areas are affected, and “strawberry foot rot” when distal extremities are involved.

Diseases of the Skin

Autoimmune Skin Disorders

Pemphigus Foliaceus

Definition and Etiology

Pathophysiology

Clinical Signs

Diagnosis

Therapy

Prognosis

Pemphigus Vulgaris

Bullous Pemphigoid

Alopecia Areata

Hypersensitivity Disorders

Atopic Dermatitis

Definition and Etiology

Clinical Signs

Diagnosis

Therapy

Urticaria

Definition and Etiology

Pathophysiology

Clinical Signs and Differential Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Therapy

Milk Allergy

Erythema Multiforme

Vasculitis

Drug Eruption

Contact Dermatitis

Definition and Etiology

Clinical Signs

Diagnosis

Therapy

Bacterial Diseases

Dermatophilosis (Streptothricosis, Rain Scald, Lumpy Wool, Strawberry Foot Rot)

Definition and Etiology

Clinical Signs

Diseases of the Skin

Chapter 40