Diseases of the Respiratory Tract

Anatomy

The nasal passages and larynx are also relatively narrow. The nasolacrimal orifice is positioned on the medial aspect of the lateral cartilaginous wall of the nasal cavity and is usually just beyond what may be seen without an endoscope. This narrowness may be an adaptation to moisten and warm inspired air in the dry, hot, or cold native environments. Regardless of the cause, the narrowness of the airway allows small amounts of compromise to severely restrict air flow and also means that many diagnostic or therapeutic modalities such as paranasal endoscopy and nasogastric or nasotracheal intubation are more difficult to perform on camelids than on some other species. Of the passages, the ventral meatus is the largest, and its ventromedial component represents the widest, straightest path to the larynx. Its dorsal component is approximately half the diameter and often too narrow to allow passage of a tube or endoscope. Therefore, it is helpful to manually press either of those items as ventromedially as possible during entry in to the nose.

Examination

Whenever lower respiratory disease is suspected, information of lung function may be obtained from arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis. Camelids have a number of superficial arteries, but the most commonly used are found on the medial aspects of the limbs and are thus more accessible in neonates and debilitated older animals in lateral recumbency than in more vigorous individuals. The median artery is found between the shoulder and the elbow, running along the craniomedial aspect of the humerus. Its pulse is usually palpable, although the structure of the artery itself usually is not. It is usually approached perpendicularly (see Figure 37-1). The saphenous artery is often both visible and palpable from medial midthigh to below the stifle. It is usually approached in a near-parallel fashion, often from its dorsal aspect to avoid puncturing the accompanying vein (Figure 37-2). Both arteries are useful in neonates; the saphenous vein is also used extensively in adults.

Figure 37-1 Obtaining blood from the median artery. Note the perpendicular approach on the dorsomedial aspect of the humerus.

Figure 37-2 Obtaining blood from the saphenous artery. Note the parallel approach on the medial aspect of the distal femur. The artery itself is visible and palpable.

Endoscopy and bronchoscopy allow direct visualization of the mucosa and discharges and are especially useful for diagnosing obstructions, aspiration, inflammatory conditions, or lungworms. The ventromedial aspect of the ventral meatus is most useful. Although externally narrow, it widens considerably at the level of the molars; with a small enough endoscope and sufficient lubrication, valuable information can be obtained. With persistence, a 6-millimeter (mm) external diameter scope will pass on most crias and adult alpacas, and adult llamas may accommodate 9-mm scopes fairly easily. In dyspneic camelids, endoscopy does reduce available airway and may lead to distress of the patient, so procedures should be completed as quickly as possible. Dorsal displacement of the soft palate may exacerbate respiratory compromise.

Transtracheal or transendoscopic wash or bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) may be used to collect information on infections, parasitic infestations, and cytologic abnormalities. Transtracheal wash using catheters or commercial kits for foals may be performed after clipping and surgically preparing the ventral midline of the neck a few centimeters beyond halfway down the trachea and infiltrating the site with a local anesthetic.1 Transendoscopic tracheal washes yield similar results, except possibly on bacteriologic culture, and the endoscope may be wedged in a bronchus for a BAL.

Pleural fluid may be obtained from healthy camelids or more readily from those with subacute to chronic hypoproteinemia.1 Fluid is best obtained approximately one third to half way up the thorax, at the sixth or seventh intercostal space. The area should be clipped, aseptically prepared, and infused with local anesthetic. A needle, cannula, or chest tube may be used, depending on how much fluid is expected, and how flocculent it is likely to be. Normal pleural fluid contains less than 1500 nucleated cells per microliter (cells/µL), with lymphocytes making up at least 80% of these cells.1 Pleural fluid usually has protein concentrations less than 2.7 grams per deciliter (g/dL), but as with abdominal fluid, outliers are possible.

Diseases of the Respiratory Tract

Dorsal Displacement of the Soft Palate (Pharyngeal Collapse)

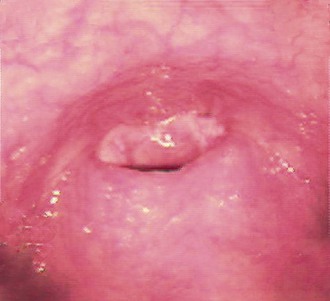

The most common cause of dyspnea is dorsal displacement of the soft palate, possibly compounded by dorsal pharyngeal collapse or epiglottic entrapment. In most cases, the underlying cause is unknown, but it is postulated that this is part of the stress response, especially in weakened or sedated camelids. In some cases, fatigue of the airway musculature caused by chronic high airway resistance or a neuromuscular defect may play a role. Clinical signs include dyspnea, stridor, open-mouthed breathing, dorsiflexion of the head and neck, regurgitation, nystagmus, and death. Definitive diagnosis requires upper airway endoscopy (Figure 37-3), but the diagnosis can often be inferred, as endoscopy of patients in respiratory distress may be unnecessarily life threatening. Possible treatments include administration of nasal oxygen, maintaining the head and neck in extension, placing a towel over the eyes to reduce sensory input, reversal of sedative medications, and tracheostomy. When stress is the causative factor, handling to administer medications, draw blood samples, maintain the neck in a certain position, or perform other diagnostic or therapeutic procedures may worsen the condition. Such camelids may improve if allowed to recover on their own. However, camelids with spontaneous dorsiflexion rarely improve without some degree of intervention. When this appears to be a permanent condition, a permanent tracheostomy may be necessary and greatly improve the animal’s quality of life.

Arytenoid Chondritis and Laryngeal Abscessation

Laryngitis with abscessation not involving the cartilage was identified in one 10-day-old cria with possible partial failure of passive transfer.2 No respiratory signs were noted, but it is likely that they would have developed had the cria lived longer. Mannheimia hemolytica was isolated.

Retropharyngeal Lymphadenopathy

Enlargement of the retropharyngeal lymph nodes may lead to occlusion of the upper airway and dysphagia. This finding is relatively rare in camelids and may be the result of neoplastic change or infection. The most common neoplasm of the area is lymphoma.3 The most common infection is likely to be Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis, although this is more likely to affect the submandibular lymph nodes, rather than the retropharyngeal nodes.4,5 Penetrating foreign bodies may also lead to infection in that area with a variety of bacteria introduced.

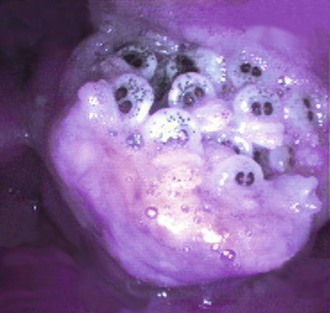

Nasal Bots

Infestations of the caudal nasal passages and dorsal pharyngeal region by nasal bots larvae from sheep (Oestrus ovis) or deer (Cephenemyia sp.) have been reported.6–8 Reports of deer nasal bots are currently confined to the western parts of the United States (California, Colorado, Oregon). Infestation occurs during fly season. Populations of the definitive host (sheep, deer) are usually found nearby. Both genera of fly are viviparous and deposit live larvae near the external nares of the host. Larvae colonize the upper airway leading to an exudative, granulomatous reaction and enlargement of adjacent soft tissue (Figure 37-4). On maturation, larvae are sneezed or coughed back onto the ground and develop into flies.

Most reports involve individual camelids, but herd outbreaks have occurred. Clinical signs are mainly from the physical narrowing of the upper airway. These include sneezing, coughing, respiratory stridor mainly on inspiration, nasal discharge possibly with mild epistaxis, exercise intolerance, and open mouth breathing. Pulmonary auscultation is usually normal but is complicated by sounds referred from the upper airway. Affected camelids are afebrile and have normal clinical pathology data except for the changes caused by stress. Most cases occur in adults, but one case of a 9-month-old llama has been reported. Many also have a history of treatment failure with antibiotics.

Upper Airway Malformations

Congenital upper airway malformations are relatively common in New World camelids. Among the more common are choanal atresia (10.4% of reported congenital defects in one study), wry face (7%), and cleft palate (3%).9 Subepiglottic cysts and hypoplastic trachea are less common. All of these impede air flow or heighten risk of aspiration.

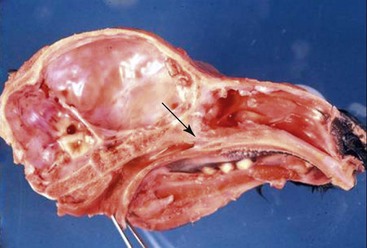

Choanal atresia is anatomically well described. It results from failure of the buccopharyngeal membranes to completely rupture during the early second trimester of fetal development, leaving membranous or bony obstructions over one or both nasal passages (Figure 37-5). Camelids with unilateral lesions may thrive into adulthood, showing little more than a heightened respiratory rate, open-mouthed breathing, or dyspnea when stressed. Bilaterally affected neonates are born with little or no ability to breathe nasally. Thus, clinical signs start immediately or soon after birth. Affected crias typically display open-mouthed breathing, with the lips pulled away from the mouth, stertor (inspiratory or expiratory), and pronounced nostril flaring (Figure 37-6). They often have difficulty eating and are at high risk for aspiration. Air flow at the nostrils is absent or reduced, and soft rubber tubes cannot be passed nasally beyond the level of the eye. Definitive diagnosis may be achieved by endoscopic examination with a pediatric endoscope (up to approximately 6 mm diameter), plain radiography, contrast radiology, in which approximately 5 to 10 milliliters (mL) of contrast (preferably an organic iodide to reduce risk of aspiration complications) is instilled into each nasal passage and the nose held in dorsal extension (Figure 37-7), or more advanced imaging techniques that allow the nasal passages to be displayed in slices. Aerophagia and hyperinflated lungs may also be seen. Endoscopy or contrast radiography reveals imperforate membranes or bony obstruction. Mucoid fluid may obscure the actual obstruction. Plain radiography reveals bony obstruction only and may be difficult to interpret. Clinical pathology data reflect stress or secondary aspiration pneumonia. Blood oxygenation is usually poor. Tracheostomy or surgical repair are possible and provide immediate relief, but camelids frequently outgrow these stomata and repeated procedures may be necessary.10

Figure 37-6 Open-mouthed breathing in an alpaca cria with choanal atresia. The nostrils moved in synchrony with inspiration in spite of no air flow.

Figure 37-7 Contrast radiographs of a cria with choanal atresia. Five to 10 milliliters (mL) of iohexol are placed in each nostril, and the nose held in an elevated position.

Similar problems are seen in camelids with severe facial distortion. They usually have a patent airway, although reduced in size. Diagnosis of the disorder is suggested by physical examination with possible endoscopic or radiographic confirmation. Surgical repair or tracheostomy may be necessary. Less is known about the heritability of this disorder, although a genetic basis is suspected.

Cleft palate is relatively common in camelids, some of which also have other congenital malformations.9 The airway is not specifically narrowed with this disorder. Aspiration is the greatest danger. Affected camelids frequently cough after eating and may have milk come out the nose. Some clefts are large enough to be seen on oral examination, although many affect only the caudal palate and require endoscopy to diagnose. Surgical repair is uncommon but may be successful with the smaller clefts.11 Camelids with large defects tend to aspirate at a very young age, whereas those with smaller defects may thrive for a longer period. No information is available concerning heritability in camelids.

Fungal Rhinitis and Sinusitis

True fungal infections of the nasal passages are rare in New World camelids. Turbinate infection by Rhizopus spp., together with nodular pneumonia and meningoencephalitis, was identified in a single llama with various cranial nerve deficits and eventually weight loss.12

Sinus infection with osseous proliferation and facial deformation was associated with an Aspergillus-like organism in a llama.13 Infections of the sinus or nasal passages may be difficult to diagnose. Most lead to bone deformation, bone lysis and proliferation, and soft tissue densities that may be seen on radiographs or cross-sectional imaging studies. Smaller masses or those involving the airway may be identified by endoscopy. Biopsy with or without fungal culture is necessary to distinguish these masses from tumors.

Infection on the skin of the nares by Conidiobolus coronatus in two llamas led to proliferation of tissue, chronic nasal discharge, and eventual occlusion of the nasal passages.14,15 Conidiobolus is a tropical fungus and most common in the Gulf Coast region in the United States, but one infected llama was a lifelong resident of Illinois. Diagnosis was achieved by histopathologic examination of tissue sections and fungal culture. Systemic antifungal medications have been used successfully in other species, but in the single treated llama case report, infected tissue was surgically removed after iodides and topical fungicides failed to resolve the lesion.

Snake Bite

Although snake envenomation affects several organ systems, the propensity for camelids to be bit on the lips or nose warrants the discussion here. Bites occur during seasons of snake activity, usually late spring and the summer. Most reports involve the Western diamondback in California or the smaller prairie rattlesnake in Colorado.16,17 The venom of these snakes contains a combination of enzymatic and nonenzymatic toxins. The overall effects are local tissue digestion, anticoagulation, hemolysis, vasculopathy, and hypotension. Eastern diamondbacks have a more hemolytic effect, and the Mojave rattlesnake has a presynaptic paralytic neurotoxin. Neurotoxin also is present sporadically in other species of pit vipers. In addition to the venom, bites are also often contaminated with a variety of microorganisms, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Clostridium, and Bacteroides fragilis.

Affected camelids generally have severe local swelling, which, in the case of bites on the face, may cause severe lip, nose, and eyelid edema and occasionally tracks to the laryngeal region and neck. Swollen areas often exude sanguinous fluid, and close inspection may reveal paired fang marks. Hemorrhagic diathesis appears to be more common in camelids bit in Colorado than in California. Swelling may also occlude air flow, leading to dyspnea, nostril flare, stridor, and tachypnea and cause dysphagia. Systemic signs of envenomation include bruxism, signs of shock, hyperthermia, tachycardia, cardiac arrhythmias, recumbency, lethargy, ileus, and anorexia. Further obtundation and other neurologic signs, respiratory signs, and colic may occur with progression of envenomation. Obviously, if the bite is on another part of the body such as a leg, signs referable to that body part will be present, possibly in the absence of respiratory signs. Local signs often worsen over the first 48 to 96 hours.

Local wound care should be performed on weeping or necrotizing lesions. Fasciotomy may also release internal pressure and prevent secondary lesions. The use of antivenin has not been explored extensively. It appears to improve survival in most species but usually must be given within hours of envenomation. In one report, a camelid appeared to have an anaphylactic reaction to equine-derived antivenin.16 Use of ovine-derived antivenin has not been reported.

Neoplasia

Airway tumors are rare in camelids. Fibrosarcoma was identified in one elderly alpaca, in which the tumor arose from the anterior aspect of the nasal septum and led to near-occlusion of one nostril. Additionally, a variety of tumors arising from the digestive structures of the mouth may affect the airway by their presence. These include squamous cell carcinomas, odontogenic neoplasms, and ossifying fibromas that appear to arise from a tooth.18,19 If masses encroach on the airway, unilateral mucopurulent nasal discharge, reduced nasal airflow, and gross distortion of the face or nasal passages may be present. Radiography, endoscopy, or advanced imaging techniques may be used to diagnose and observe the extent of the mass. Biopsy is necessary to confirm the tissue type. Treatment usually involves resection, with or without postoperative chemotherapy.

Lymphoma or malignant round cell tumor compressing the trachea has been described in a llama and an alpaca.3,20 Both were 7 to 8 years old, older than the median age for camelids with lymphoma. In the llama, a cervical node was palpably enlarged, but the mass was entirely intrathoracic in the alpaca. In addition to the typical signs of emaciation and partial inappetence, affected camelids have tachypnea or dyspnea. If the mass is palpable, diagnosis may be achieved by aspirate or biopsy. If it is intrathoracic, imaging studies are likely to reveal its presence. Local resection and chemotherapy may lead to some resolution of signs and period of remission.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree