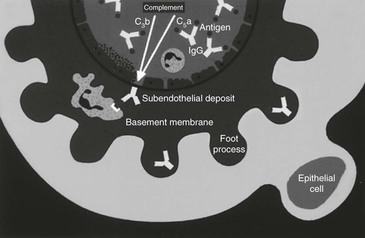

David C. Van Metre, Dominic R. Dawson Soto, Consulting Editors ▪ Equine Renal System Dominic R. Dawson Soto, Consulting Editor Thomas J. Divers • Alexandra J. Burton Acute renal failure (ARF) in the horse is usually due to exposure to nephrotoxins or vasomotor nephropathy (e.g., hypoperfusion or ischemia). The most common pathologic lesion with ARF is acute tubular necrosis (ATN). Administration of aminoglycoside antibiotics is one of the most common causes of ATN in the horse. These antibiotics exert their toxic effect by accumulating within proximal tubular epithelial cells. Their entrance into the tubular epithelial cell is thought to be via urine after filtration through the glomerulus.1 Once toxic amounts are sequestered within the cell, cellular metabolism is disrupted and tubular cell swelling, death, and sloughing into the tubular lumen occur. Release of lysosomal enzymes and intracellular accumulation of calcium are likely involved in cell death. Most cases of aminoglycoside nephrotoxicity are not due to drug overdosing or administering the drug to an azotemic patient.2 The healthy kidney can usually tolerate a single major overdose (i.e., 10 times the normal amount) without detrimental effects, so toxicity is almost always the cumulative effect of repeated administration of aminoglycosides. Because the drugs are water soluble and thus highly distributed in extracellular fluid (ECF), their clinical pharmacokinetics are strongly influenced by variations in patient ECF volume owing to disease state or age, so different doses and dose intervals may be required to attain desired peak and trough levels depending on patient specifics.3,4 Because renal cellular uptake of gentamicin is saturable, nephrotoxicity is associated with insufficiently low trough levels rather than excessively high peaks.5 The maximal trough concentration to minimize the risk of nephrotoxicity is unknown in horses. In humans, trough gentamicin concentrations over 2 µg/mL have been associated with nephrotoxicity.6,7 However, optimal trough concentration for minimizing nephrotoxicity after administration of gentamicin to humans is controversial, with recommendations ranging from maintaining a trough less than 2 µg/mL to maintaining a period of less than 0.5 µg/mL for at least 4 hours.8–10 Nephrotoxicity typically develops after several days of aminoglycoside administration to horses with diarrhea or septicemia that are not adequately hydrated,11 or because of other factors that may exacerbate a decrease in renal perfusion (e.g., concurrent treatment with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]). The shift to once-daily aminoglycoside dosing in horses, compared with previous dosing of aminoglycosides two or three times daily, has become a standard practice that likely reduces the potential for nephrotoxicity (by ensuring a longer period of the day with appropriate serum trough concentrations) but still provides a similar therapeutic response.12–15 Prolonged administration (>10 days) of aminoglycoside antibiotics without monitoring of aminoglycoside trough concentrations or serum creatinine concentration is a common history with aminoglycoside nephrotoxicity in the horse. Typically, gentamicin or amikacin may be safely administered for longer than 10 days if the patient is adequately hydrated and appropriate trough concentrations and creatinine concentration are maintained. With regard to the latter, experimental induction of gentamicin nephrotoxicity in ponies was reflected by a rather small increase (0.3 mg/dL) in creatinine.16 Although it has not been proven, the neonatal equine kidney is likely more susceptible to aminoglycoside toxicity than the adult kidney. This is probably reflective of the prolonged elimination half-life seen in foals.4,17 Sick foals appear to be at greater risk for aminoglycoside nephrotoxicity,18 although this may simply reflect an increased incidence of septicemia in sick neonates and longer courses of treatment with aminoglycosides. When aminoglycosides are administered to high-risk patients (concurrent dehydration or neonates), volume deficits must be replaced and serum trough concentrations or creatinine monitored frequently.19 Aminoglycoside nephrotoxicity rarely develops in horses receiving appropriate fluid therapy. Increased urinary sodium excretion and fluid diuresis appear to have a protective effect on the kidney. In contrast, hypokalemia (or total body potassium depletion) and low calcium intake may predispose horses to aminoglycoside nephrotoxicity by decreasing urine output.20 Supplementation with oral electrolytes (e.g., 1 to 2 oz of NaCl and KCl daily) may be of benefit to horses being treated with aminoglycoside antibiotics by increasing water intake and urine output and replacing potassium deficits in anorectic horses. In contrast, furosemide should not be administered prophylactically in an attempt to prevent aminoglycoside nephrotoxicity.21 In patients with prerenal azotemia that receive aminoglycoside antibiotics, it is important to monitor creatinine closely and consider prolonging the interval between drug administration until volume deficits are corrected. However, because nephrotoxicity is a cumulative effect of repeated dosing, delay of administration of the initial dose of an aminoglycoside pending rehydration of a critical patient (e.g., septic neonate, extremely dehydrated horse) is unwarranted. Aminoglycoside nephrotoxicity should be considered in horses that become inexplicably depressed and inappetent while being treated with aminoglycosides or within a few days after aminoglycoside therapy is discontinued. Renal failure can develop even after the drug is withdrawn, so monitoring renal function 2 to 4 days after discontinuing aminoglycoside therapy may be advised in high-risk patients. Polyuria may be observed before the onset of depression and anorexia or, if the patient becomes oliguric, mild stranguria and repeated posturing to urinate may be observed. A tentative diagnosis of nephrotoxicity is based on history of aminoglycoside use and supportive laboratory data. Abnormal laboratory findings associated with tubular damage that may be detected before onset of azotemia include enzymuria and cylindruria.16,22 Although these parameters can be monitored for early detection of tubular injury, their finding does not necessarily indicate if or when aminoglycosides should be discontinued or to what degree the interval of administration should be prolonged.23 When ARF from aminoglycoside use develops, it usually manifests as nonoliguric to polyuric renal failure; outcome is generally favorable so long as the duration of ARF is not prolonged and other underlying disease processes can be corrected. Peritoneal or pleural dialysis, plasmapheresis, or hemodialysis might be considered as methods to lower serum concentrations of nephrotoxic agents and uremic toxins. However, the amounts removed by a single use of some of these therapies are small and generally not worthy of pursuit in horses with nephrotoxic renal failure.24 Acute tubular necrosis and development of ARF subsequent to rhabdomyolysis (myoglobin pigment) can occur if the episode of tying up is severe and/or the associated dehydration is prolonged.25,26 Pigment nephropathy can also occur secondary to any other causes of muscle necrosis. Observation of grossly discolored urine is not a prerequisite for development of renal failure. Hemolysis, which may be secondary to a variety of toxins and primary conditions, appears to be a less common cause of pigment nephropathy than myopathy, although ARF can occur sporadically. Horses with severe hemolysis or those with hemolysis accompanied by disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) are at greater risk of developing pigment nephropathy.27 In one study, 40% of 32 horses with red maple toxicosis and hemolysis had evidence of renal insufficiency, but it was not found to be an important risk factor for mortality.28 Renal failure due to pigment nephropathy should be suspected in horses that become anorectic and more depressed during the week after an episode of tying up or during a hemolytic crisis. Measuring serum activities of creatine kinase (CK) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) may help confirm that ARF has developed in association with rhabdomyolysis. There is little preformed creatinine in muscle, so rhabdomyolysis alone does not produce an increase in it.29 Vitamin K3 (menadione) was a common cause of ATN and ARF in certain parts of the United States before its withdrawal from the market. Nephrotoxicity can occur rapidly after a single parenteral dose of the menadione sodium bisulfite form of vitamin K3.30,31 Development of ARF was thought to be idiosyncratic and likely involves direct tubular damage via oxidative stress and pigment nephropathy subsequent to hemoglobinuria.30,31 Although horses are very sensitive to its nephrotoxic effects, oral supplementation of menadione with a view to enhancing bone strength was recently investigated in horses in Japan, and no nephrotoxicity was reported.32,33 Most horses do not experience appreciable adverse effects from NSAIDs as long as they are administered at the proper dose and animals are not dehydrated. However, NSAID use may produce ARF in an occasional horse when excessive doses are administered or when dehydration is not corrected promptly.22,23 The lesion produced by NSAID toxicity in horses is medullary crest necrosis, which can be manifested by gross hematuria.34–38 Unless severe, this lesion rarely causes overt clinical signs, and creatinine may actually decrease with fluid therapy. An occasional horse may also develop chronic interstitial nephritis and nephrolithiasis after prolonged use (months to years) of NSAIDs at recommended doses.39 The renal medullary rim sign, an ultrasonographic abnormality consisting of a hyperechoic band parallel to the corticomedullary junction, has been demonstrated in NSAID toxicity in adult horses and foals.40,41 Presence of concurrent gastrointestinal (GI) disease (ulceration) and protein-losing enteropathy would further support NSAID toxicity in both acutely and chronically affected horses. Interestingly, acute interstitial nephritis was the predominant renal histopathologic lesion recorded in clinically normal Miniature donkeys administered NSAIDs (ketoprofen (2.2 mg/kg IV), flunixin (1 mg/kg IV or PO), or phenylbutazone (2.2-4.4 mg/kg IV or PO) twice daily for 2 weeks.42 Also, in contrast to horses who may not show increases in serum creatinine while on fluid therapy or until severe renal compromise occurs, donkeys may show more acute increases in serum creatinine with NSAID toxicity.42 When renal blood flow decreases because of dehydration or redistribution of cardiac output, counteracting vasodilatory mediators are produced and released within the kidney to attenuate the decrease in renal blood flow. The best studied of these vasodilatory mediators include renal prostaglandins (PGI2 and PGE2) and dopamine. Although the role of renal prostaglandins in controlling basal renal blood flow is likely insignificant, they are important mediators of vasodilation during periods of renal hypoperfusion.43 Renal prostaglandin production is several-fold greater in medullary tissue, such that action of these mediators leads to a greater increase in inner cortical and medullary blood flow. It should not be surprising that the lesion associated with NSAID toxicity is renal medullary crest necrosis (due to ischemia).44 Similarly, it is important to remember that NSAID use in dehydrated or hypovolemic patients increases the risk of acute nephrosis.45 Vitamin D intoxication may result from ingestion of feed additives or plants (e.g., Cestrum diurnum) containing high amounts of vitamin D metabolites or from parenteral administration of vitamin D.46–48 Cholecalciferol (D3) is thought to be more toxic than ergocalciferol (D2) in the horse.47 In general, horses do not need dietary supplementation with vitamin D if they are exposed to adequate sunlight and have access to green forages. The effect of vitamin D supplementation is cumulative, so signs of toxicity may not develop until several weeks after supplementation was started. Clinical signs of vitamin D intoxication may be referable to the musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, or urinary systems.48 Calcification of tendons and ligaments results in lameness, and calcification of cardiac muscle and great vessels can lead to cardiovascular problems. Mineralization of tendons and ligaments may be detected directly by palpation or indirectly through ultrasonographic imaging. Heart murmurs may accompany calcification of the great vessels, and ultrasonographic imaging of the heart and kidney may also reveal evidence of mineralization. Further clinical signs of renal toxicity include polyuria and weight loss. Abnormal laboratory findings with vitamin D intoxication include azotemia, isosthenuria, hypochloremia, and elevations in both serum calcium and phosphorus concentrations. The latter combination of hypercalcemia and hyperphosphatemia is unusual for any other disease in the horse, although it may be seen with neoplasia on rare occasions. A definitive diagnosis of vitamin D toxicosis can be made by measuring serum concentrations of 25-OHD3, 25-OHD2, and 1,25-(OH)2D. Treatment of vitamin D intoxication includes removal of the inciting cause (feed or medication), fluid diuresis, and corticosteroid administration. Provision of feeds low in both calcium and phosphorus may be of benefit in less severely affected horses, but treatment is usually unrewarding once clinical signs due to tissue mineralization have developed. Accidental ingestion of heavy metals may result in ATN and ARF in horses. Mercury, cadmium, zinc, arsenic, and lead are all nephrotoxic but are rare causes of renal failure in the horse. Mercury has been used experimentally to study renal failure in horses,49,50 and there are reports of ARF in horses that have had legs “blistered” or “sweated” with products containing inorganic mercury.51,52 Because inorganic mercury also causes severe damage to intestinal mucosa, signs of GI irritation (e.g., increased salivation, oral erosions, colic, hemorrhagic diarrhea) predominate with mercury intoxication. Further evaluation may reveal oliguria. Exposure to excessive amounts of zinc and cadmium can result in nephrocalcinosis and renal failure, but gait deficits (resulting from osseous effects, particularly in foals) and ill-thrift are more likely presenting complaints than oliguria.53 Laboratory findings with heavy metal intoxication are characteristic for ATN: azotemia, hyposthenuria to isosthenuria or anuria (depending in part on concurrent hydration status), hyponatremia, and hypochloremia. In horses with ARF concurrent with GI disease, as with mercury toxicity, severe hypocalcemia may be present. A tentative diagnosis of mercury intoxication may be made from history of exposure, clinical signs of erosive GI disease, and oliguric renal failure. The diagnosis can be confirmed by measuring increased blood and tissue (kidney and liver) concentrations of the metal. In addition to judicious fluid therapy, treatment of ARF induced by exposure to heavy metals should include parenteral dimercaprol, 5 mg/kg intramuscularly (IM) initially, followed by 3 mg/kg IM q6h for the remainder of the first day, then 1 mg/kg IM q6h for two or more additional days, as needed, and 1 lb of charcoal orally. Visceral analgesics (flunixin meglumine) and sedatives (xylazine or detomidine) are often necessary to control abdominal pain. Acorn poisoning is less common in equids than cattle but has been reported in horses.54 Death in horses is usually due to erosive GI disease, changes in vascular permeability, and resulting shock rather than a consequence of uremia. Immature leaves and green acorns are considered more toxic than mature acorns because the former have a higher tannin content. Clinical signs may include diarrhea, edema, and body cavity effusion, and laboratory evaluation usually reveals azotemia, isosthenuria to hyposthenuria, hyponatremia, and hypochloremia. Detection of increased urinary excretion of phenols may be useful to confirm the diagnosis. Several other drugs and agents (oxytetracycline, polymyxin B, amphotericin B, imidocarb dipropionate, ochratoxins, pyrrolizidine, cantharidin toxicosis [blister beetle poisoning], and the nematode Halicephalobus) have been suspected of causing nephrotoxic ARF in horses. When high doses of oxytetracycline (up to 70 mg/kg) are administered to neonatal foals for correction of limb contracture, ARF is a potential complication, especially if the foals are dehydrated or have concurrent sepsis or hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy.55 With renewed interest in polymyxin B as an adjunct treatment for endotoxemia, it is prudent to remember that this drug also has nephrotoxic potential. However, experimental studies have demonstrated that the risk of polymyxin B nephrotoxicity is low, especially when it is conjugated with dextran 70.56 Amphotericin B also has considerable nephrotoxic potential, but it is rarely administered systemically to horses. Imidocarb dipropionate, used in treating Babesia equi infections, has been shown to cause reduced renal function after multiple dosing.57 Ochratoxins have the potential to produce ATN, but ARF caused by ochratoxins has not been documented in horses. Similarly, pyrrolizidine alkaloid poisoning may cause renal disease in horses, but failure is unlikely. Blister beetle poisoning (cantharidin toxicosis) may cause abdominal pain, shock, hematuria, diaphragmatic flutter, dysuria, and renal dysfunction in horses fed alfalfa hay grown in regions where the beetles are prevalent.58 One report of renal failure, as well as brain involvement, was associated with granulomas caused by the nematode Halicephalobus.59 Anecdotal reports exist of horses developing renal disease after administration of bisphosphonates for treatment of orthopedic disease. Prudence should be used as renal disease is a reported complication in other species after bisphosphonate administration.60 Any condition that causes sustained marked hypotension or release of endogenous pressor agents can initiate hemodynamically mediated (vasomotor) ARF. Although poorly documented, vasomotor ARF may be more common than nephrotoxic ARF in the horse. However, renal compromise due to a combination of vasomotor and nephrotoxic mechanisms probably occurs more frequently than clinically identified in sick horses receiving drugs with nephrotoxic potential. Hemorrhagic shock, severe intravascular volume deficit (e.g., as with enterocolitis), septic shock, and coagulopathy are important risk factors for vasomotor ARF in horses.61 Another cause may be adverse drug reactions, including those accompanying intravenous (IV) administration of vitamin and mineral products or immunomodulators. The predominant lesion in vasomotor nephropathy is ATN, although diffuse renal cortical or renal medullary necrosis may also occur in some cases. Clinical signs of vasomotor ARF are nonspecific and more often referable to the primary disease (e.g., hemorrhage or diarrhea). Additional subtle signs (e.g., more marked depression and anorexia than would be expected with the primary disease), with or without signs of mild colic, may increase suspicion of ARF. If sedation for colic signs is deemed necessary, xylazine or detomidine can be administered if intravascular volume and blood pressure are not overly compromised. Occasionally, horses with severe ARF may also be ataxic or manifest neurologic signs similar to hepatoencephalopathy. Oliguria, often seen as a lack of expected urination in response to fluid therapy, is an important early indicator of vasomotor ARF, and production of dilute urine (specific gravity <1.020) that may be discolored (hematuria or hemoglobinuria) may be observed when urine is eventually voided. If urine produced is grossly clear, microscopic hematuria is usually present and will produce a positive result on reagent strip analysis of urine. Glucosuria due to severe proximal tubular damage may also be detected in an occasional horse with vasomotor ARF. Although the pathophysiologic relationship to ARF is not well defined, diarrhea and severe laminitis may develop in more serious cases of vasomotor ARF. Although subclinical glomerular damage likely accompanies some diseases affecting horses, especially immune-mediated disorders (e.g., purpura hemorrhagica), acute glomerulonephritis (GN) is a rare clinical problem.62 A syndrome of arteriolar microangiopathy and intravascular hemolysis that causes distention of glomerular capillary loops with fibrin thrombi and accumulation of large amounts of proteinaceous debris in the Bowman capsule has also been described in a few horses.63 Affected horses presented with oliguric ARF accompanied by hematuria, proteinuria, and intravascular hemolysis; response to treatment was poor. The cause of the syndrome in horses is not definitively known. Renal lesions resemble those found with hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) in humans, which is caused by toxins of Escherichia coli. In a recent case report of HUS with glomerular thrombotic microangiopathy in a postpartum mare, E. coli O103:H2 was isolated from the uterus and gastrointestinal tract.64 Glomerulopathy with ARF caused by Streptococcus mitis has also been documented as a component of toxic shock in a horse.65 Bacterial toxins, a consumptive coagulopathy, immune complex deposition, vasoactive amines, and hemodynamic alterations may all be contributors to this rare syndrome in horses. Acute glomerulopathy should also be considered in horses with severe ARF that do not have a predisposing primary disease leading to vasomotor ARF and that have not been exposed to nephrotoxins. Gross hematuria, proteinuria, and oliguria would support an acute glomerulopathy, and renal biopsy can be pursued to confirm the lesion. Acute interstitial nephritis is a rare syndrome of ARF accompanied by rapid elevations in creatinine and clinical signs of uremia. Renal lesions include interstitial edema with a mild inflammatory infiltrate. Although adverse drug reactions (idiosyncratic) may be a cause, the etiopathogenesis of this disease in horses is unknown. In humans, eosinophilic infiltrates in renal biopsy tissue are supportive of adverse drug reaction. Although there are no published reports of the syndrome in horses, the author (TJD) has examined three horses with apparent acute interstitial nephritis. However, experimentally, in Miniature donkeys, interstitial nephritis (rather than medullary crest necrosis) was the predominant renal histopathologic lesion recorded following IV administration of NSAIDs twice daily for 2 weeks.42 Because of the pronounced interstitial edema that may accompany this disease, treatment with corticosteroids may be of benefit in suspect cases. Krista Elise Estell ARF due to infection with Leptospira interrogans should be considered when an underlying renal disease is not apparent and there has been no exposure to nephrotoxins. L. interrogans serovar pomona has been documented as a cause of interstitial nephritis in horses, though the most common pathologic isolates are L. interrogans serovar kennewicki in the United States and L. interrogans serovar icterohaemorrhagiae and Leptospira kirchneri serovar grippotyphosa in the United Kingdom.66–70 The most frequent clinical sign in both experimental and natural infection is fever, but anorexia and depression may also be present, and hematuria was observed in one foal.71 Clinical pathologic abnormalities include azotemia and isosthenuria without bacteriuria. Leptospiruria is not a consistent finding, making diagnosis difficult. Diagnosis of Leptospira spp. can be achieved by urine polymerase chain reaction (PCR); administering furosemide and testing the second voided sample may increase sensitivity of this test. Serum titers performed by microscopic agglutination rise quickly after experimental infection.72 Demonstration of a rising titer or baseline titer above 1 : 6400 indicates active infection.73 Treatment includes fluid therapy and penicillin. ARF should be suspected in patients showing more marked depression and anorexia than would be expected with the primary disease process and in those that fail to produce urine within 6 to 12 hours of initiating fluid therapy. Rectal palpation in horses with ARF may reveal enlarged, painful kidneys in some cases. Enlargement can be confirmed by renal ultrasonography, which may also reveal perirenal edema, loss of detail of the corticomedullary junction, or dilation of renal pelves.74–76 However, subtle changes in renal architecture can be difficult to detect via ultrasound, and sensitivity of this diagnostic modality largely depends upon operator experience and image quality. The diagnosis of ARF is confirmed on the basis of history, potential exposure to nephrotoxins, clinical signs, and laboratory findings. Relative to baselines, the increase in serum or plasma creatinine concentration is often several-fold greater (e.g., up to 5 to 15 mg/dL) than that of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) concentration (e.g., up to 50 to 100 mg/dL), resulting in a BUN/creatinine ratio that is often less than 10 : 1. Hyponatremia, hypochloremia, and hypocalcemia are usually present, and in more severe cases, hyperkalemia, hyperphosphatemia, and metabolic acidosis may also be detected. In addition to assessment of the magnitude of azotemia and alterations in serum or plasma electrolyte concentrations and acid-base balance, urinalysis should be performed on all horses in which ARF is suspected. As mentioned, a low urine specific gravity (<1.020) in the face of dehydration and gross or microscopic hematuria are common findings with ARF. Evidence of more substantial proximal tubular damage, including increased urinary enzyme activity and glucosuria, may be detected in some horses. Significant proteinuria (urine protein/creatinine ratio > 2 : 1 [see Chronic Renal Failure]) would support the presence of glomerular disease. Examination of urine sediment may reveal casts and increased numbers of erythrocytes and leukocytes, and the amount of urine crystals may be decreased. Increased fractional clearances of sodium and phosphorus are also common findings with ARF. It is important to remember that administering IV fluids to healthy horses will also result in increased fractional clearances of sodium, chloride, and phosphorus.77 Electrolyte clearances are ideally determined using the initial urine sample voided after admission or a sample collected by catheterization (i.e., before urine is substantially altered by fluid therapy). The most accurate assessment of renal function involves glomerular filtration rate (GFR), which can be measured by performing timed urine collections (inulin and endogenous or exogenous creatinine clearances) or assessing plasma disappearance of several compounds (sodium sulfanilate, phenolsulfonphthalein, or radiolabeled substances).78 Recently GFR has been determined in a foal using computed tomography (CT) with single-slice dynamic acquisition and Patlak plot analysis.79 In a clinical setting, measurement of GFR in cases of ARF is rarely pursued because multiple measurements are required to assess changes in GFR, and prognosis for recovery is more likely related to the duration of decreased GFR rather than to the magnitude of the decrease. Because of the inverse relationship between GFR and creatinine, changes in GFR can be more practically assessed by daily serum creatinine measurement. Glomerular injury and tubular necrosis can be further confirmed by performing a renal biopsy, but biopsy is often not indicated because the diagnosis of ARF is usually evident. In a recent retrospective study of 151 renal biopsies in horses carried out at 14 different equine hospitals, biopsy specimens yielded sufficient tissue for a histopathologic diagnosis in 94% of cases, but diagnoses had only fair (72%) agreement with postmortem findings.80 Immunofluorescent (IF) testing and electron microscopic (EM) examination are routinely performed on human renal biopsy samples to assess mechanisms of renal injury and extent of damage to glomerular and tubular basement membranes. If such detailed evaluation of renal biopsy tissue were routinely performed in horses with ARF, better information regarding etiopathogenesis and prognosis would likely be provided by the pathologist. At present, renal biopsy is most often indicated to evaluate horses with ARF when exposure to nephrotoxins or another underlying primary disease process is unapparent. Life-threatening hemorrhage is a potential complication of renal biopsy. The above-mentioned study found a complication rate of 11.3%, generally associated with hemorrhage or signs of colic. Treatment for complications was required in only 3% of cases, and there was only one fatality.80 Risk factors for complications included biopsy of the left kidney, a diagnosis of neoplasia, and low urine specific gravity.80 Biopsy of the right kidney with ultrasonographic guidance, usually through the seventeenth intercostal space, is the preferred procedure.81 Proper instrumentation (automatic or spring-loaded biopsy instruments) and adequate restraint (stocks and sedation) are important considerations. Renal tissue collected should be placed in formalin for histopathologic examination, as well as frozen (or placed into additional media specified by the testing laboratory) for IF testing and EM examination. Although biopsy of the right kidney alone usually is adequate for assessment of the disease process affecting both kidneys, samples of the left kidney can also be collected by guiding the biopsy instrument through the spleen. Again, ultrasonographic guidance is especially vital when collecting a biopsy from the left kidney or when biopsy of a specific area of either kidney is desired. The general principles of ARF treatment in the horse are similar to those recommended for humans.82,83 Initial therapy should always focus on judicious IV fluid administration to replace volume deficits and correct electrolyte and acid-base abnormalities. The magnitude of azotemia and serum concentrations of sodium, chloride, potassium, and bicarbonate should be monitored daily. Horses with polyuric ARF often require sodium and chloride replacement. This can be accomplished by using 0.9% NaCl as the fluid administered or through supplementation of these electrolytes in grain feedings or as oral pastes. Serum potassium concentration in horses with nonoliguric ARF is often normal, and except for postrenal problems (e.g., obstruction or rupture), therapy intended to lower serum potassium is usually unnecessary. Similarly, it is usually unnecessary to correct the mild hypocalcemia that can accompany ARF in horses. After correcting volume deficits and electrolyte and acid-base abnormalities, an attempt should be made to determine whether the animal is oliguric or nonoliguric (polyuric); the prognosis for recovery appears to be more favorable with nonoliguric ARF. This often becomes apparent by simple observation: oliguric horses fail to produce expected amounts of urine in the initial 12 to 24 hours of IV fluid therapy and the bedding remains dry. Nonoliguric horses repeatedly void moderate volumes of dilute urine during the initial 6 to 12 hours of treatment. Edema can develop rapidly in horses with oliguric or anuric ARF and is often initially noticed in the conjunctiva (Fig. 34-1). Other manifestations include generalized subcutaneous swelling of dependent areas, progressing to tachypnea and altered mental status if pulmonary and/or cerebral edema develop. In horses with prerenal azotemia (as opposed to intrinsic ARF), serum creatinine concentration should decrease by at least 30% to 50% within the initial 24 hours of fluid therapy. In contrast, creatinine concentration may remain unchanged or even increase in ARF. During therapy for ARF, regular assessments of attitude, vital parameters, packed cell volume, and total plasma protein concentration are important. Monitoring should also include measurement of body weight once or twice daily (patients should not gain weight with continued fluid therapy after initial rehydration) and comparison of fluid input with fluid (urine) output. Although there is no convenient method of collecting all urine voided by ambulatory foals or mares, urine output can be rather easily quantified in male horses by placing a urine collection device around the abdomen.84 When desired, monitoring urine output in critically ill foals and mares can be accomplished by use of an indwelling Foley catheter and urine collection bag (closed system), but ascending infection is a risk. In severely ill patients, especially those with vasomotor nephropathy, systemic blood pressure (BP) can be monitored to confirm that fluid therapy has been adequate to restore BP. Some horses may remain hypotensive (systolic BP < 80 mm Hg) despite administration of large volumes of IV fluids, owing to extravascular accumulation as edema or a third-space fluid. If systemic BP remains low, hypertonic saline, dobutamine, or other pressor agents may be required to restore BP and glomerular filtration. Fluid and sodium replacement in horses with oliguric renal failure and normal systemic BP must be monitored closely; overzealous fluid administration to horses with oliguric or anuric ARF will result in edema formation. Central venous pressure (CVP) can also be monitored as a more precise measurement of fluid balance in critical patients. CVP is measured with a manometer with the baseline at the level of the right atrium, attached to an IV catheter placed into the anterior vena cava via the jugular vein (normal CVP in horses, <8 cm H2O). In horses that remain oliguric after 12 to 24 hours of appropriate fluid and electrolyte replacement and restoration of systemic BP, furosemide at 1 mg/kg IV q2h should be administered. Unfortunately, furosemide treatment is often ineffective in increasing renal blood flow, GFR, and tubular flow in horses with ARF.83,85 Continuous infusion of furosemide at 0.12 mg/kg/h, preceded by a loading dose of 0.12 mg/kg IV, was considered superior to intermittent use in one study.86 If urine is not voided after the second dose, administration of mannitol (1 g/kg IV as a 10% to 20% solution) and/or a dopamine infusion (3 to 7 µg/kg/min IV) can be instituted. Dopamine administration should only be performed in a hospital setting where heart rate and BP can be monitored frequently and development of tachycardia and hypertension avoided. Dopamine use for selective renal vasodilatory and natriuretic actions has been called into question because most studies in humans have not demonstrated prevention of ARF in high-risk patients or improved outcome in those with established ARF87; in one study, dopamine actually worsened renal perfusion in human patients with ARF.88 Further, the drug may precipitate serious cardiovascular and metabolic complications in critically ill patients. If these treatments are successful in converting oliguria to polyuria (may require 24 to 72 hours), they can be discontinued, but maintenance of urine production must be monitored closely over the next few days. Fortunately, the majority of horses with ARF resulting from ATN are nonoliguric rather than oliguric, and furosemide, mannitol, or dopamine are unnecessary. When this treatment approach to oliguria remains unsuccessful for more than 72 hours, the prognosis becomes grave. One study of horses with colic or colitis found that horses with persistent azotemia after 72 hours of fluid therapy were three times as likely to die or be euthanized as the horses without persistent azotemia.89 However, dialysis therapy may be a further treatment option in selected patients. Hemodialysis has been successfully used to treat two adult horses with myoglobinuric ARF90,91 and a neonatal foal with oxytetracycline-induced ARF.55 Peritoneal dialysis has been attempted in a few horses with nephrotoxic-induced ARF, but omental plugging of the catheter has limited its success, and special dialysis catheters are required for effective fluid exchange. Pleural dialysis is another option for which fluid exchange is less problematic. Hemodialysis or dialysis would likely be most effective in horses with nephrotoxic ARF, whereas vasomotor nephropathy is best treated by addressing the predisposing condition and instituting appropriate fluid therapy. After volume deficits have been restored and polyuria achieved, patients usually need only continued fluid therapy (0.9% NaCl or another balanced electrolyte solution, 40 to 80 mL/kg/day) to promote a continued decrease in creatinine. Fluid therapy may have to be continued (20 to 40 mL/kg/day) for several days until creatinine returns to the normal range or a steady-state value and the horse is eating and drinking adequate amounts. Supplementation with oral electrolytes (1 to 2 oz NaCl twice daily) will also promote greater fluid intake and diuresis. Potassium supplementation (1 oz KCl twice daily) may also be required because diuresis results in kaliuresis. When horses remain anorectic during treatment, the addition of 50 to 100 g dextrose/L fluids can provide needed calories, and if anorexia persists for several days, caloric intake may have to be provided by nasogastric tube feeding or total parenteral nutrition. Within the week after fluid therapy is discontinued, creatinine should be measured again to ensure it has not increased. Occasionally, creatinine may not decrease to below 2 to 3 mg/dL despite continued fluid therapy. As long as the horse is eating and drinking well, IV fluids can be discontinued. In some horses, further recovery will be seen as a return of creatinine to normal range within the next couple of months, whereas in other patients a persisting elevation in creatinine indicates permanent loss of renal function. During the first 1 to 3 days of life, the creatinine concentration in newborn foals is often 30% to 40% higher than in their dams.92 The cause is unclear but likely related to an inability of creatinine to equilibrate rapidly across placental membranes. As supportive evidence, creatinine concentration of normal amniotic fluid (which contains fetal urine) at term is approximately 10 mg/dL (and may exceed 30 mg/dL in some mares).93 This transient increase in creatinine, which may occasionally exceed 20 mg/dL in premature foals, has been called a “spurious” elevation—a misleading characterization because creatinine truly is increased. Further, in a recent retrospective study, 20 of 28 foals with hypercreatinemia had clinical signs of mental abnormalities and/or seizures.94 When elevated creatinine is detected in an otherwise healthy foal (that has also been observed to urinate normally), there may be no cause for alarm, but if levels do not decline rapidly after birth (or remain >2.5 mg/dL on day 3 of life), peritoneal or retroperitoneal accumulation of urine, renal hypoplasia, or other causes of renal failure should be considered. Unlike creatinine, BUN values in foals are typically low (<10 mg/dL) after day 2 and remain low for the first several months of life. This finding can be attributed to the anabolic state of the growing foal. Urinalysis results in normal neonatal foals are also different from those in adult horses. Specifically, for 1 to 2 days after birth, normal foals may have marked proteinuria resulting from filtration of small-molecular-weight proteins absorbed with colostrum. Fluid intake on a predominantly milk diet is high in foals (250 mL/kg/day, compared to 50 mL/kg/day of water intake by adults), so after day 2 of life, foal urine is hyposthenuric (specific gravity 1.002 to 1.006) and remains that way for several months. Finally, urinary enzyme activity and sodium and chloride clearances may be greater than adult values, and urine pH is neutral to acidic in foals.95 ATN is the most common pathologic lesion causing ARF in neonatal foals. Many cases develop during or after episodes of diarrhea, likely caused by poor perfusion (vasomotor nephropathy) subsequent to varying degrees of dehydration. Surprisingly, the diarrheal disease in some affected foals does not appear to be serious, but they may develop ARF. Similar to adult horses with ARF, the prominent clinical signs are depression and development of edema. Abnormal laboratory findings include azotemia, hyponatremia, hypochloremia, and hypocalcemia. Foals are more likely to develop significant hyperkalemia and hyperphosphatemia than adult horses with ARF. A urine specific gravity less than 1.018 and microscopic hematuria are usually also found in foals with ARF. Urine output of sick neonates should be monitored closely because they may become oliguric to anuric 12 to 24 hours before significant depression or azotemia is recognized. In addition, fluid retention during incipient ARF is another cause of inappropriate weight gain (e.g., >2 kg in 24 hours), which can often be detected before obvious edema develops. Nephrotoxicity, most often due to aminoglycoside or tetracycline administration, is another important cause of ARF (usually nonoliguric) in neonatal foals. As in adult horses, the recent change to once-daily aminoglycoside dosing appears to have decreased the incidence of hospital-acquired ARF in foals. Seriously ill and/or premature foals appear to be at even greater risk of nephrotoxicity than term foals, owing to reduced renal clearance.96 Although there is a general impression that amikacin may be less nephrotoxic than gentamicin in foals, no data exist to support this notion. Regardless of which aminoglycoside antibiotic is selected, monitoring trough concentrations (<2 mg/mL for gentamicin, <4 mg/mL for amikacin) is warranted to decrease the risk of aminoglycoside toxicity in high-risk neonates. It should be noted that the actual optimal trough concentrations are unknown in horses and are based on those used in human medicine. Dosage adjustment may be necessary in seriously ill neonates or premature foals, because renal clearance may be decreased, necessitating an increased dosing interval to achieve low enough trough concentrations. Judicious fluid therapy to correct dehydration and maintain BP is an important precaution. To complicate matters, foals also have a larger volume of distribution than adult horses and require an increased dose of aminoglycosides to attain therapeutic peak concentrations.4,97 Volume of distribution may be increased even further in premature foals and with certain disease processes that increase extracellular fluid volume. Treatment principles for ARF in neonates are essentially the same as for adult horses (see earlier discussion). However, greater attention must be paid to monitoring responses to fluid therapy, including twice-daily measurement of body weight. Although foals that have a bout of ARF in the neonatal period would seem at greater risk of developing chronic renal failure later in life, no long-term follow-up study has corroborated this speculation. Multifocal renal abscesses or infarcts may be a complication of neonatal septicemia and can lead to ARF. Actinobacillus equili is the most common pathogen causing renal abscesses, but affected foals often die or are euthanatized because of overwhelming sepsis before clinical signs of ARF develop. Foals 2 to 4 days of age appear to be at greatest risk of developing acute Actinobacillus septicemia; when this problem is suspected, IV therapy with penicillin and gentamicin (at prolonged dosage) is recommended (see Chapters 18 and 20). Subsequent fibrin deposits in the kidney have also been identified in some foals with septicemia and ARF.98 Thomas J. Divers • Theresa Lynn Ollivett Chronic renal failure (CRF) in the horse may be divided by clinical and pathologic findings into two broad categories: primary glomerular disease and primary tubulointerstitial disease.1,2 However, pathology in one portion of the nephron usually leads to altered function and eventual pathology in the entire nephron, so CRF is an irreversible disease process characterized by a progressive decline in GFR. The rate of decline in GFR is variable among affected horses, making the short-term (e.g., months to 2 years) prognosis guarded to favorable while the long-term prognosis remains poor. Primary glomerular diseases that can lead to CRF in horses include GN, nonspecific glomerulopathy, renal glomerular hypoplasia, and amyloidosis. Primary tubulointerstitial diseases causing CRF include incomplete recovery from ATN, pyelonephritis, nephrolithiasis, hydronephrosis, renal dysplasia, and (rarely) papillary necrosis. Collectively, the latter disorders produce pathology categorized as chronic interstitial nephritis. Unfortunately, because renal disease is often advanced when horses are first presented for clinical evaluation, the inciting cause leading to CRF may be difficult to ascertain, and end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) may be the pathologic diagnosis. The inciting cause may more likely be discerned from the history (long term) rather than clinical findings at presentation, especially for primary tubulointerstitial diseases. Adjunctive diagnostic evaluation, including laboratory assessment, renal ultrasonography, and renal biopsy, may provide further evidence to document the inciting cause. Proliferative GN, indicating increased cellularity of the glomerular tufts consequent to influx of inflammatory cells and proliferation of mesangium, is the most common glomerular disease causing CRF in horses. It is thought to result from deposition of circulating immune complexes along the glomerular capillaries or in situ formation along the glomerular basement membrane (GBM) (Fig. 34-2). Deposition of immune complexes causes activation of complement and vasculitis (type III hypersensitivity response). In one study, deposits of immunoglobulin (Ig)G and complement along the GBM were found through IF staining in a large percentage (22 of 53) of horses at necropsy.3 However, only 1 of these 53 horses developed CRF. Thus, although immune (antigen-antibody) complex deposition and subclinical GN may be common in horses, progression to CRF appears to be an infrequent occurrence. In this necropsy survey the predominant IF staining pattern was granular (patchy deposits of immune complexes and complement along GBM), but linear deposits were found in two horses. The latter finding was supportive of true autoimmune disease with more diffuse deposition of anti-GBM antibodies (type II hypersensitivity response) along the basement membrane antibody. Streptococcal antigens have been suggested to be an important trigger for development of proliferative GN,4 and in one horse with CRF, streptococcal antigens were confirmed to be present in diseased glomeruli.5 Although equine infectious anemia virus is the only other antigen that has been detected in glomeruli of horses with proliferative GN,6 subclinical GN likely accompanies other chronic infections in horses. It has also been suggested that equine GN may also be associated with either mixed or monoclonal cryoglobulins forming antibody-antibody glomerular deposits.7 In one horse with no evidence of viral or bacterial infection, deposits consisting solely of IgM were identified within the GBM.8 Fortunately, GN in most patients is rarely of clinical significance. Chronic interstitial nephritis (CIN) and fibrosis may be the most common cause of CRF in horses. Interstitial nephritis (tubulointerstitial disease) usually develops as a sequela to ATN consequent to exposure to nephrotoxins or vasomotor nephropathy. Other causes include drug-induced interstitial nephritis, urinary obstruction, pyelonephritis, renal hypoplasia/dysplasia, and papillary necrosis. Although the majority of horses that develop ARF attributable to these causes recover with apparently normal renal function (they remain nonazotemic), a few may survive with significant loss of renal functional mass and subsequently (often years later) develop signs of CRF due to CIN.9 In horses younger than 5 years of age that develop CRF unattributable to other causes, anomalies of development (e.g., renal hypoplasia, dysplasia, polycystic kidney disease) should be strongly suspected2,10–13 (Fig. 34-3). Bilateral septic pyelonephritis is a rare cause of CRF in horses.14–16 Pyelonephritis is usually due to an ascending infection and often accompanied by nephrolithiasis or ureterolithiasis. Multiparous mares (especially those with a history of dystocia) and horses with bladder paralysis are at greater risk for bacterial colonization of the lower urinary tract and subsequent development of ascending infection. Chronic distention with bladder paralysis compromises the integrity of the ureteral orifices, leading to vesiculoureteral reflux and pyelonephritis. With long-standing bladder paralysis, the ureteral orifices may appear wide open during cystoscopic examination, and in an occasional affected horse, the endoscope can be advanced into the ureter with little resistance. With unilateral pyelonephritis, adequate renal function is usually maintained by the contralateral kidney, but passage of small uroliths into the bladder can lead to recurrent urethral obstruction. Gram-negative organisms appear to be the most common causative agents, although Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, or Corynebacterium spp. may be isolated in some cases, and mixed bacterial infections are not uncommon. Other reported causes of CRF in horses include amyloidosis,17 neoplasia,18 focal glomerulosclerosis-like disease,19 and chronic oxalate nephrosis.20 One study described CRF secondary to polycystic kidney disease in an aged pony with hematuria; the pony also had hepatic cysts.21 Renal amyloidosis has been reported only in horses used for production of antiserum.17 So-called oxalate nephropathy in horses is likely a misnomer; the presence of oxalate crystals in renal tissue of horses with CRF is typically a consequence rather than the cause of CRF.20 The most common clinical sign observed in horses with CRF is weight loss.2 A small plaque of ventral edema, usually between the forelimbs, is another frequent finding.2,22 Moderate polyuria and polydipsia (PU/PD) are usually present at some stage of the disease process, but PU/PD may not be noticed except by the astute owner or trainer.2 Dysuria is generally not reported unless CRF is due to pyelonephritis, which may be associated with bladder paralysis, lithiasis, and lower urinary tract infection (UTI). Normal equine urine is rich in crystals and mucus, making a prediction of urine abnormalities on gross observation difficult. However, hematuria or pyuria (gross or microscopic) may be reported in some (but not all) horses with pyelonephritis, urinary calculi, or neoplasia. Often, urine produced by horses with CRF is light yellow and transparent because it is relatively devoid of crystals and mucus. Accumulation of dental tartar (especially on the incisors and canine teeth [Fig. 34-4]), melena, and oral ulcers are other findings that may be detected in horses with CRF. Growth may be stunted in horses with renal hypoplasia, dysplasia, or polycystic kidney disease. Although abdominal pain would be expected in horses with obstructive nephroliths or ureteroliths, colic signs are not often reported in horses with lithiasis producing obstruction of the upper urinary tract.9,23 Rarely, signs of uremic encephalopathy such as obtundation, anxiety, head pressing, and seizure may be present.24,25 Clinicopathologic findings in horses with CRF vary depending on appetite, diet, and the cause and severity of renal damage. Most horses with clinical signs of CRF have moderate to severe azotemia (creatinine usually ≥5 mg/dL). The BUN/creatinine ratio may vary depending on protein intake, muscle mass, hydration, and degree of azotemia, but is usually 10 : 1 or greater. Mild hyperkalemia, hyponatremia, and hypochloremia are typically found in horses with CRF. Hypercalcemia, with serum concentrations sometimes exceeding 20 mg/dL, appears to be a laboratory finding with CRF that is unique to the equid. One study of horses evaluated at referral hospitals for renal failure reported 56% of 39 horses with CRF to be hypercalcemic,26 and a larger study of 99 horses with CRF found 67% to be hypercalcemic.2 Hypercalcemia in horses with CRF is not due to hyperparathyroidism27; its presence or absence appears to be more closely related to dietary intake than to the magnitude of azotemia. For example, four of four nephrectomized ponies fed alfalfa hay developed marked hypercalcemia,28 whereas serum calcium concentration remained within the normal range in four of four nephrectomized ponies fed grass hay (although filterable calcium did increase).29 Similarly, hypercalcemia in horses with spontaneously occurring CRF can resolve within a few days of changing diet from alfalfa to grass hay.13 Serum phosphorus concentration in horses with CRF is usually normal to decreased, and hypophosphatemia is more often detected with concurrent hypercalcemia. Hypermagnesemia may also be detected in some horses with CRF. Acid-base balance usually remains normal until CRF becomes advanced, but metabolic acidosis is a common finding in horses with end-stage disease. Many horses with CRF are moderately anemic (packed cell volume, 20% to 30%) secondary to decreased erythropoietin production by the diseased kidneys. Those with CRF resulting from GN frequently have hypoalbuminemia and hypoproteinemia, and horses with advanced CRF of any cause may also have mild hypoproteinemia associated with intestinal ulceration. Hyperglobulinemia may be detected in horses with immune-mediated diseases or chronic pyelonephritis. Horses with CRF can also develop hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia (hyperlipidemia), and horses with advanced CRF may occasionally have grossly lipemic plasma.30 Urinalysis findings may also vary depending on the cause of CRF. As mentioned, urine collected from horses with CRF is relatively devoid of normal mucus and crystals, making samples transparent. Urine specific gravity is typically in the isosthenuric range (1.008 to 1.014), although heavy proteinuria in an occasional horse with GN may produce values up to 1.020. Quantification of urine protein concentration (as for cerebrospinal fluid) is required to accurately assess proteinuria. Urine protein concentration in normal horses is usually less than 100 mg/dL, and the urine protein/creatinine ratio should be less than 1 : 1.31,32 With significant proteinuria, urine protein/creatinine ratio is usually greater than 2 : 1.5 In the earlier stages of GN, excessive urine protein is primarily albumin, but with progression of glomerular pathology, an increasing amount of globulin is also lost in the urine. Horses with CIN usually do not have significant proteinuria. Hematuria (gross or microscopic) may be present with pyelonephritis, urinary calculi, or neoplasia and can produce trace proteinuria, but urine protein/creatinine ratio usually remains less than 2 : 1. Horses with septic pyelonephritis would be expected to have pyuria (>5 leukocytes/high-power field) and significant bacteriuria on sediment examination, but these findings are not consistently detected; a urine sample should be submitted for quantitative bacterial culture in all horses with CRF. More than 10,000 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL of urine are typically found with infection, although lower numbers do not always rule out septic pyelonephritis. A diagnosis of CRF is most often made in horses with azotemia and isosthenuria that present with a complaint of weight loss or decreased performance. As discussed earlier, determining the inciting cause of CRF can be difficult because the disease has often advanced to ESKD when horses are initially presented for evaluation. Urinalysis does not often reveal the cause of CRF except in some horses with pyelonephritis. In theory, assessment of urine protein concentration and urine protein/creatinine ratio should be helpful in separating glomerular disease from tubulointerstitial disease, but in practice, these laboratory measures have not consistently been elevated in horses with histopathologic evidence of GN. However, detection of moderate to heavy proteinuria (urine protein/creatinine ratio > 2 : 1) without hematuria provides support for glomerular disease. Rectal examination may be helpful in determining the cause of CRF. Horses with pyelonephritis, as well as those with ureteral calculi, often have enlarged ureters that can be palpated dorsolaterally as they course through the retroperitoneal space. Although kidneys of horses with CRF are often small with an irregular surface, these changes are not always apparent on palpation of the caudal pole of the left kidney. The right kidney cannot usually be palpated in the horse unless it is greatly enlarged or displaced caudally by the liver or a mass. Ultrasonographic imaging is useful for evaluating kidney size and echogenicity and may reveal fluid distention (hydronephrosis, pyelonephritis, polycystic disease) or presence of nephroliths.33–35 Horses with significant renal parenchymal damage and fibrosis often have loss of detail of the corticomedullary junction, and echogenicity of renal tissue may be similar or even greater than that of the spleen. In contrast, intravenous pyelography (IVP) provides little information in adult horses, and its use is generally limited to foals less than 50 kg. When hematuria or dysuria accompanies CRF, cystoscopic examination can be helpful in determining the side (right vs. left) from which renal hematuria is originating and further allows assessment of the ureteral orifices and urine flow from each kidney. As described under Acute Renal Failure, measurement of GFR provides the most accurate assessment of renal function, and repeated measurements at monthly or longer intervals can be useful to monitor rate of progression of CRF. It is also a useful measure to document a reduction in renal function in horses that are thought to have early CRF, before significant azotemia has developed. GFR can be measured by several methods, including urinary clearance of endogenous or exogenous creatinine, inulin, or technetium-99m diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (99mTc-DTPA) (all require timed urine collections) or plasma disappearance of sodium sulfanilate, phenolsulfonphthalein, or radiolabeled compounds (e.g., 99mTc-DTPA).13,36–39 Assessment of renal function by nuclear scintigraphic imaging of the kidneys has also been described, but in horses this technique appears to be better for documenting decreased individual kidney function (i.e., with unilateral or asymmetric disease) than for quantitative assessment of GFR.40,41 In most clinical settings, performing a 24-hour endogenous creatinine clearance is the most practical and economical method for measuring GFR. The major challenge is application of a urine collection device for collection of all urine produced. Once urine has been collected, a well-mixed sample is submitted to the laboratory, along with a sample of serum obtained during the collection period, and GFR is estimated by the following standard clearance formula:

Diseases of the Renal System

Acute Renal Failure

Toxic Nephropathies

Aminoglycosides

Pigment Nephropathy

Vitamin K3.

Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs

Vitamin D

Heavy Metals

Acorn Poisoning

Miscellaneous Drugs and Agents

Vasomotor Nephropathy

Acute Glomerulopathy

Acute Interstitial Nephritis

Leptospirosis

Diagnosis

General Principles of Treatment

Serum Creatinine Elevations in Newborn Foals

Acute Renal Failure in Foals

Septic Renal Disease in Foals

Chronic Renal Failure

Causes

Proliferative Glomerulonephritis

Chronic Interstitial Nephritis

Pyelonephritis

Miscellaneous Causes

Clinical Signs and Laboratory Findings

Diagnosis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Diseases of the Renal System

Chapter 34