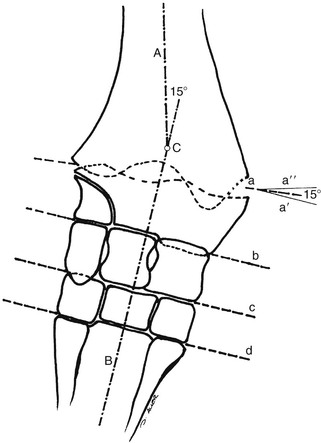

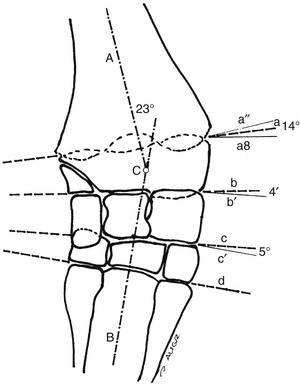

Robin M. Dabareiner, Consulting Editor A. Berkley Chesen Physitis is a term used to describe a developmental orthopedic condition where there is a disturbance in endochondral ossification at the physis, or growth plate. Of the developmental orthopedic diseases (osteochondrosis, physitis, subchondral bone cysts, flexural limb deformities, cuboidal bone malformation, acquired angular limb deformities, and juvenile arthritis), physitis is the most common.1,2 In one study of 1711 Irish Thoroughbred foals, 67% had signs of developmental orthopedic disease.2 The term physitis may better be defined as physeal dysplasia, since there is typically no evidence of an inflammatory process.3 Physitis due to copper deficiency and interactions with molybdenum, zinc, and sulfates, as well as in calves raised on slatted floors, has been seen in growing cattle.4 Two common antagonists of copper include zinc, which when prevalent at high levels prevents absorption of copper by the body, and molybdenum, which is found in alfalfa.5 Other animals in which physitis has been reported include show rams being heavily fed and sheep and goats with pregnancy-associated ephiphysitis.4 Physitis typically affects the given physis during its active growth phases. Many factors have been implicated as causes of physitis in horses, including4: 4. Intake of high levels of carbohydrates, causing hormonal changes affecting the physis 5. Improper mineral balance (e.g., copper or zinc deficiencies) 6. Excessive or deficient calcium intake 7. Excessive exercise, especially on hard ground, may cause strain on maturing cartilage More recently, physitis has been implicated as a complication after treatment with a transphyseal screw for angular limb deformities in the distal radius. It was shown that the single transphyseal screw had a significantly higher complication rate of physitis when compared to the technique using screws and wires.6 Physitis in horses is seen mainly in three specific locations at certain ages. Foals ranging in age from 3 to 6 months most commonly have signs of physitis at the distal metacarpal/metatarsal growth plate (with or without involvement of the proximal physis of the first phalanx).7 Older foals (8 to 24 months) may have signs of physitis at the physis of the distal radius.7 Less frequently, the distal physis of the tibia may be involved. Physitis is characterized by firm swellings that may be warm and painful upon palpation. Typically the swellings are medial and due to increased weight bearing on this portion of the limb.7 Foals may or may not be lame. Radiographic changes include a sclerotic, roughened physis with an irregular metaphyseal shape.2 If physitis continues, the growth plate may close prematurely, leading to an irreversible angular limb deformity (usually a varus deformity due to decreased growth on the medial physis).2 A diagnosis of physitis is usually made by appreciation of the clinical signs, including warm, sometimes painful, firm swellings in the locations mentioned. Physitis at the fetlock may appear to have an hourglass appearance if the proximal physis of the first phalanx is affected.7 A convex appearance just proximal to the distal tibial and radial physis may be seen early in the disease process.7 Recently a quantitative method for detecting physitis was investigated in Thoroughbred foals.2 This method was based on the observation that when the physis is enlarged, both the metaphysis and ephiphysis are more concave.8 Results of this study showed that epiphyseal concavity may indicate the degree of physeal swelling by using the maximum second-derivative value of that contour.2 Radiographically, physitis is characterized by a growth plate that is irregularly thickened with sclerotic adjacent bone.2 Treatment of physitis should begin with management changes. Special attention should be given to the nutrition of these foals and weanlings. Ensuring a proper balance of minerals, especially calcium, phosphorus, and adequate amounts of trace minerals like copper and zinc, is necessary. Copper is required for successful cross-linking of collagen. When a copper deficiency exists, the cartilage matrix weakens and microfractures occur.5 Because mare’s milk is very low in copper, foals rely on hepatic stores gained during the last trimester of gestation.5 One study showed that supplementation of mares with copper during gestation significantly reduced radiographic signs of physitis in their foals at 150 days of age.9 Supplementation of foals did not affect the incidence of physitis in the same study. The results of this study strongly suggested that on farms with a high incidence of physitis, copper supplementation of mares during the second half of gestation may be beneficial in preventing physitis in their foals.9 A general reduction in energy is necessary to slow growth rates and, when necessary, decrease body weight. Total concentrate for nursing foals should be 0.5 to 0.75 kg/100 kg body weight, 1 to 1.5 kg/100 kg for weanlings, and 0.5 to 1 kg/100 kg for yearlings.9 Physitis involves varying degrees of discomfort. For horses with very painful, warm physes, judicious use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) is indicated. Exercise restriction—specifically stall rest—is indicated in affected horses. Without exercise restriction, these horses continue to load the physes, which may lead to permanent conformational changes like angular limb deformities. With early detection and treatment, the athletic prognosis for physitis is good. Jason C. Mez Osteochondrosis is a developmental orthopedic disease characterized by failure of, or a defect in, endochondral ossification; it can lead to cartilage flaps, osteochondral fragments, or subchondral bone cysts. It is classified as a developmental orthopedic disease (DOD) along with physitis, angular limb deformities, subchondral bone cysts, flexural deformities, incomplete ossification of the cuboidal bones, and juvenile arthritis.1 Chondrodysplasia and dyschondroplasia are more descriptive terms because they imply a primary defect in cartilage maturation, but their use is generally reserved for abnormalities of limb and vertebral development. The terms osteochondrosis, osteochondritis, and osteochondritis dissecans have all been used synonymously in discussing the condition. To maintain consistency and avoid confusion, the following designations are used here: osteochondrosis refers to the disease, osteochondritis refers to the synovial inflammatory response caused by the disease, and osteochondritis dissecans refers to the condition when a cartilaginous flap is identified.2 Osteochondrosis has been recognized in most domestic species, including horses, swine, and less often in cattle, sheep, and goats. The main focus has been in horses, owing to the economic impact and performance-limiting characteristics of the disease, and in swine, owing to effects on production traits3 and development of comparative models for study of the disease.4 Osteochondrosis can present with a variety of clinical signs that are frequently recognized in juvenile animals. Effusion of the affected joint with or without accompanying lameness is common. The tarsocrural and femoropatellar joints are most often affected, but the condition can be seen in any joint. In young animals, physitis (i.e., inflammation at the physeal plate) can have a similar appearance, with generalized enlargements adjacent to synovial structures. Osteomyelitis can cause a periosteal reaction that, if located in the area of a joint, can have a similar appearance. Septic arthritis can closely mimic the signs of osteochondrosis, but the associated lameness is often much more severe. Physitis, osteomyelitis, synovitis, and septic arthritis should all be considered in the differential diagnosis of osteochondrosis in juvenile animals. In older animals the clinician should consider synovitis, osteoarthritis, and trauma in the differential diagnosis. Osteochondrosis is generally diagnosed in horses when they are started into training programs or begin athletic activity. They often present with a complaint of joint effusion that can be acute or insidious. Lameness is usually nonapparent to mild, except in cases with large osteochondral fragments or subchondral bone cysts. Severe cases seem to be more common in the stifle, and associated clinical signs may be present in foals as young as 6 months. Warmblood horses generally present later, at 3 to 4 years of age, because it is common practice to delay training until this stage. Reports in cattle indicate that young, intact male, purebred animals are most often affected. The typical clinical signs are lameness with associated joint effusion. Osteochondrosis in swine has been associated with a syndrome known as “leg weakness.” Affected animals can show a range of signs from mild lameness to inability to rise and inability or refusal to mount.5 Evaluation of performance data from swine herds can be a useful indicator of osteochondrosis, because it has been shown to have a significant effect on production traits.3,6 Being that production animals are usually slaughtered prior to 2 years of age, recognizable clinical signs of the disease in cattle and swine may only be apparent in breeding animals. Osteochondrosis can be found in any diarthrodial joint, but sites of predilection exist in all species affected. In horses the stifle and hock are most frequently affected. In the stifle, in order of frequency, the lateral trochlear ridge of the femur, medial trochlear ridge of the femur, trochlear groove, and distal end of the patella are affected.7 The medial femoral condyle is the site of predilection for subchondral cystic lesions. In the hock, in order of frequency, the distal intermediate ridge of the tibia, lateral trochlear ridge of the talus, and the medial malleolus are affected.7 Predilection sites in cattle are similar to those in horses, with the hock and stifle most often affected and similar distribution in the joints.8 Swine show a slightly different pattern, with the medial condyle of the humerus and femur most frequently affected.6 Animals presenting with signs of joint effusion and lameness should undergo a thorough physical examination. A compete blood cell count (CBC) indicating a septic process, along with radiography, help differentiate osteomyelitis, septic physitis, or septic arthritis from osteochondrosis. In cases with any indication of a septic process, appropriate cultures should be taken. Horses should be observed in motion and given flexion tests, using local and intraarticular anesthesia to localize the site of lameness. Swine and cattle can be observed in their normal surroundings for signs of lameness. Once localized, the affected joint should be radiographed, as should the corresponding joint on the contralateral limb in the tarsocrural and femoropatellar joints, because lesions are often bilateral (Fig. 38-1). If lesions are detected in the metacarpophalangeal or metatarsophalangeal joint, the remaining three limbs should be radiographed because these can occur quadrilaterally.9 Lameness and effusion are more reliably seen in cases of osteochondritis dissecans and subchondral bone cysts than in osteochondrosis. Intraarticular anesthesia of the affected joint will alleviate the lameness, localizing the source. After the lameness has been localized, appropriate radiographs of both the affected area and the contralateral or quadrilateral limbs should be obtained (Fig. 38-2), as described previously. Swine and cattle will often present with signs of lameness and mild joint effusion. Careful physical examination of the restrained animal should allow the affected area to be localized and appropriate radiographs to be obtained. As with equine patients, the lesions are rarely unilateral, and corresponding limbs should be radiographed. Reviewing production records of finishing or breeding swine herds may also be of diagnostic value, because osteochondrosis has been shown to cause significant reductions in performance and production traits.3 The manifestation of osteochondrosis may not be adequately represented by clinical signs and radiographs. Clinical signs of lameness and joint effusion have been shown to precede changes within the joint, and serial radiographs may be needed to diagnose the condition.10 Radiographic abnormalities consistent with osteochondrosis of the distal intermediate ridge of the tibia and lateral trochlear ridge of the femur can return to a normal appearance by 5 and 8 months, respectively, in warmblood foals.11 Radiographs often underrepresent the severity or size of the lesion seen at surgery. Endochondral ossification is the process of bone formation that begins with a cartilage scaffold arranged in zones that are gradually replaced by bone. It occurs at the articular/epiphyseal and metaphyseal growth plates and secondary centers of ossification, such as the carpal and tarsal bones. Directly beneath the articular cartilage is a zone of resting chondrocytes that divide to form the next zone, the proliferating chondrocytes. These proliferative cells divide rapidly, organizing into columns perpendicular to the long axis of growth. The cells progress to the hypertrophic zone, where they swell and become vacuolated, and the columns become more organized. The chondrocytes in this zone also become surrounded by increasing amounts of extracellular matrix, which becomes mineralized in the zone of calcification. These columns of chondrocytes are invaded by metaphyseal blood vessels supplying nutrients from below, and bone forms on these calcified cartilage columns, creating the primary spongiosa, which is subsequently remodeled into mature bone. The exact pathogenesis of osteochondrosis is still undefined. The traditional theory is that the process of endochondral ossification is disrupted, resulting in areas of thickened cartilage. The deeper layers of these retained cartilage plugs do not receive adequate nutrients, and necrosis of the cells develops along with failure of proper ossification. These retained cartilage plugs have less structural integrity than normal cartilage and are prone to damage. Shear forces acting on the abnormal cartilage can lead to fissure formation. These fissures can then form dissecting cartilage flaps, free flaps, or fragments of cartilage and subchondral bone. When compressive forces predominate on an area of thickened cartilage, it can cause infolding of the cartilage plug. Normal endochondral ossification proceeds around the infolded plug, forming a subchondral bone cyst. This traditional theory of defective endochondral ossification is still well accepted, but recent literature suggests this may be a simplistic view of a multifactorial condition. Limited reparative responses of bone and cartilage make it difficult to determine whether the origin of a lesion is developmental or traumatic. A recent report failed to distinguish articular cartilage differences in naturally occurring osteochondrosis versus healing osteochondral fragments.12 Arthroscopic observations of normal-thickness cartilage defects and normal subchondral bone, as well as lesions occurring preferentially at single sites at the limits of articulation, suggest causative factors other than defective endochondral ossification.9 The development and spontaneous regression of osteochondrosis lesions suggest that the condition is a dynamic process that can be affected by numerous intrinsic and extrinsic factors, and a “window of susceptibility” may exist whereby lesions are repaired and normal articular development proceeds.13 These findings and observations suggest that multiple pathologic pathways exist and that a single etiologic explanation of osteochondrosis is unlikely. As with its pathophysiology, the exact etiology of osteochondrosis is unclear and likely multifactorial in origin. Several factors, including biomechanical forces, failure of vascularization, nutrition, growth rate, genetics, and hormones, have been implicated and are likely interrelated in the etiopathogenesis of the disease. The consistent distribution of lesions at specific anatomic sites within the joint implicates trauma as a causative factor. The bilateral or quadrilateral nature of the disease would indicate that trauma or biomechanical stress is a necessary factor rather than direct cause. It has been established in pigs that microtrauma or disruption of the metaphyseal blood vessels supplying the developing cartilage canals causes ischemic necrosis, failure of mineralization, and a retained cartilage plug.14 The same vascular pattern has been shown to be present in young foals, with the arterial supply crossing the ossification front from metaphyseal blood vessels to nourish the developing cartilage canals.15–17 There is little doubt that failure of vascularization, resulting in ischemic necrosis of the cartilage canal and retention of a cartilage plug, plays a role in the development of osteochondrosis in both swine and horses.18 To date, these mechanisms have not been studied in cattle. Nutritional influences have been extensively studied in relationship to osteochondrosis. Studies have focused mainly on dietary energy levels and mineral composition (copper and zinc). The growth rate of the animal is directly affected by energy intake as well as the genetic predisposition of the animal for growth and size. Animals fed high-energy levels for accelerated growth rates have a much higher incidence of osteochondrosis than those fed for lower rates of growth.4,19,20 When looking at growth characteristics in pigs, it was shown that for every 100-g increase in average daily gain during the weaning and finishing period, a 20% increase in cartilage lesions or osteochondrosis in the humeral condyle occurred.21 This is important when considering ration planning and growth rates of replacement animals, where longevity is a greater concern than in the production animal. Low copper levels and increased zinc concentrations have both been implicated in the etiology of the disease. Low copper is thought to exert its effect through lysyl oxidase, a copper-dependent enzyme essential in the cross-linking of collagen molecules. Increased levels of zinc antagonize copper and could work indirectly through a similar mechanism. There is conflicting evidence on the causative nature of low copper levels, and lesions seen in copper-deficient animals do not always mimic those of naturally occurring osteochondrosis. More recently, evidence suggests that neonatal copper levels exert a positive effect on the resolution of osteochondrosis lesions but are not directly involved in the pathogenesis of the disease.22 Genetics have been shown to be at least partially responsible in the etiopathogenesis of osteochondrosis in different species. Landrace and Yorkshire breeds of swine show a high frequency of osteochondrosis, whereas domestic pigs crossed with wild hogs do not develop the disease.4 Heritability has also been demonstrated in Standardbred trotters in the tibiotarsal and metacarpal/metatarsal phalangeal joints.23,24 A genetic component is also likely interrelated with nutrition levels because an animal must have the genetic capacity for increased growth rate and size while on high planes of nutrition. Alterations in hormone concentrations have been implicated in the etiology of osteochondrosis, but the mechanisms remain in question. Numerous hormones (e.g., insulin, somatotropin, thyroxine) are involved in the process of endochondral ossification. Physiologic or iatrogenic alterations of these hormones or their derivatives could theoretically lead to the development of osteochondrosis. The contribution of these factors to the etiology of osteochondrosis will likely not be elucidated until the molecular mechanisms of endochondral ossification are better understood. The current focus of research has been on the molecular mechanisms involved in the development of the disease. Much has been published in this area, but no definitive conclusions have yet been reached. The exact molecular mechanisms of normal endochondral ossification are not yet fully understood, making comparison to a normal process difficult to impossible. Also, the reparative process in lesions begins almost immediately, and it was shown that there is no difference between tissue types in healing, naturally occurring osteochondrosis lesions compared to surgically created fragments.12 Treatment of osteochondrosis should take several factors into account: clinical signs; lesion severity; species, age, intended use, and relative value of the animal; and owner expectations. Treatment options include both nonsurgical and surgical management. Nonsurgical management should consist of rest, controlled exercise, and dietary evaluation. Dietary mineral and carbohydrate levels should be evaluated carefully and any deficiency or excess corrected. Systemic NSAIDs and intraarticular medications like corticosteroids, hyaluronic acid, and polysulfated glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) can all be administered, but minimal clinical evidence exists to support their use. In food-producing animals the clinician must take into consideration that these are not approved treatments and that withdrawal times may not be established. Given the nature of the disease, nonsurgical management may provide a favorable outcome only in very young animals with regenerative capacity or in those with very mild lesions and minimal to no clinical signs. Animals with osteochondritis dissecans are best treated with arthroscopic surgery. Cases with no radiographic evidence of degenerative joint disease (DJD) before surgery and minimal articular damage at arthroscopy carry a favorable prognosis. Animals that show radiographic evidence of DJD before surgery or considerable damage to the articular surfaces at arthroscopy carry a guarded prognosis. Arthroscopic approaches to the joints of cattle have been described, but the procedure is more difficult than in the horse.8 In selected cases, reattachment of large cartilage flaps with absorbable poly-p-dioxanone pins may be warranted.25 Dietary evaluation of surgical patients should be included and appropriate adjustments made. Treatment of subchondral cystic lesions is still controversial, and many options are available. Nonsurgical management can be attempted and should consist of rest, controlled exercise, and intraarticular injection of corticosteroids along with hyaluronic acid or polysulfated GAGs. The prognosis is guarded except in cases with very narrow openings into the synovial cavity, and alternate treatments should be considered in refractory cases. Cysts can be treated with ultrasonographically or arthroscopically guided intralesional deposition of corticosteroids. Arthroscopic guided injections into the fibrous lining of the cyst carries a 67% success rate in horses without preexisting secondary radiographic changes.26 Arthroscopic débridement and curettage of the cystic lesion is another option with similar success rates, and horses younger than 3 years of age carry a better prognosis. Recent investigations show promise for arthroscopic débridement and curettage of lesions followed by packing the remaining defect with either a cancellous bone graft covered by a chondrocytic growth factor or with various bone substitutes, even in older horses and those with preexisting osteoarthritis.25,27 Cysts located in the proximal interphalangeal joint (PIP) are generally unresponsive to conventional treatment, and arthrodesis of the joint offers the best prognosis. Treatment of osteochondrosis in food animals is generally limited by the economic value of the animal. Show animals or valuable breeding animals may be treated by any of the methods described, and the surgical options will offer a better prognosis than nonsurgical treatment. In production herds, ration evaluation and genetic predisposition may be the only variables that can be addressed. Because production animals are slaughtered at an early age, treatment is generally unnecessary. A review of production records and estimates of monetary loss will indicate whether intervention is necessary in herd situations. Jeffrey P. Watkins Angular limb deformities are deviations in the axis of the forelimbs or hindlimbs in the frontal plane. Valgus deformity denotes a lateral deviation of the limb distal to the origin of the deformity; varus deformity denotes a medial deviation. The deformity is further described by naming the joint adjacent to the origin of the deformity; for example, carpus valgus describes an angular deformity arising in the carpal region, with lateral deviation of the metacarpus (knock-kneed conformation) (Fig. 38-3). Angular limb deformities may be either congenital or acquired. In general, they are due to laxity of periarticular supporting structures, incomplete ossification, or asynchronous growth rate. Although the underlying cause of these abnormalities remains undefined, potential causes include intrauterine malpositioning, relative immaturity, hereditary predisposition, rapid growth, dietary imbalances, osteochondrosis, and trauma.1–3 Congenital angular deformities are frequently attributed to intrauterine malpositioning and laxity of periarticular supporting structures. They typically originate in the region of the carpus and tarsus, resulting in bilateral valgus deformity. It is also common to identify a “windswept” foaling in which valgus deformity of one limb is accompanied by varus deformity of the contralateral limb. Acquired angular deformities usually occur secondary to asynchronous growth. A foal born with incomplete ossification may acquire an angular deformity secondary to crushing of the cartilaginous precursors of the cuboidal bones. A hereditary angular limb deformity of Suffolk, Suffolk crossbred, and Hampshire sheep is known as spider lamb syndrome (see later discussion). Incomplete ossification is an important cause of angular deformities originating at the carpus and tarsus. The epiphyses and cuboidal bones of the carpus (ulnar, third, and fourth carpal bones) and tarsus (central and third tarsal bones) are primarily affected.1 Ossification of the cartilaginous precursors of these bones occurs in late gestation; prematurity or relative immaturity results in the birth of a foal before these precursors are completely ossified (Figs. 38-4 and 38-5). If laxity of the periarticular supporting structures accompanies incomplete ossification, the deformity is congenital and may progressively worsen with weight bearing. If laxity is not present, the foal may be born with straight legs and later acquire an angular deformity after deformation of the precursors of the cuboidal bones during weight-bearing activity. Foals can acquire an angular limb deformity as a result of asynchronous growth at the metaphyseal and epiphyseal growth cartilages.2,3 An important cause of asynchronous growth is trauma to a portion of the growth cartilage of the physis.4 In many foals this trauma is in the form of nonphysiologic compression of the growth cartilage. Excessive exercise in foals with mild angulation and normal activity in foals with moderate to severe preexisting angular deformity may cause sufficient trauma to the growth cartilage to cause progressive deformity. Asymmetric loading also occurs when severe lameness is present. With the change from a rectangular stance with four weight-bearing limbs to a triangular stance with three weight-bearing limbs, asymmetric, nonphysiologic loading of the weight-bearing limb occurs, which predisposes it to developing an angular deformity. Because compressive forces are concentrated along the medial aspect of the growth cartilages, a varus deformity usually develops in the overloaded limb. Abnormalities of the growth cartilage that affect ossification (e.g., osteochondrosis) may also be responsible for angular deformities caused by asynchronous growth. Foals with a predisposition for rapid growth or those exposed to nutritional imbalances appear to be at greatest risk for developing the disease. Rapid growth may also result in a foal with a large body size disproportionate to its skeletal structures. This condition may cause increased compressive forces, nonphysiologic loading of the growth cartilages, and angular deformity.4 Ruminants raised in confinement may experience endochondral dysplasia and angular limb deformities if dietary iron is high or dietary vitamin D is low5 (rickets). Elevated dietary iron results in elevations in serum phosphorus, which may in turn inhibit 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol synthesis by the kidney, resulting in rickets.5 Pregnancy-associated epiphysitis in primiparous dairy goats6 can also result in angular limb deformities. When evaluating a foal with an angular deformity, important historical information includes age, onset and progression of the deformity, and intended use of the foal. The foal should be observed carefully while standing and walking to characterize the degree of deformity and determine the presence of compensatory problems or lameness. Physical examination includes careful palpation of the affected limb and a determination of whether the deformity can be corrected by manual manipulation of the limb. If the foal is examined before ossification has progressed, deformities resulting from laxity of periarticular supporting structures and incomplete ossification can be corrected manually. On the other hand, if deformities in foals born with incomplete ossification are left untreated and the cuboidal bones are in a collapsed configuration, or if deformities are the result of asynchronous growth, they cannot be corrected manually. An arthropathy should be suspected if lameness is present. Collapse of incompletely ossified cuboidal bones may result in deformation of articular surfaces and subsequent DJD. When this occurs in the carpus, the prognosis for athletic performance is guarded to poor. If the cuboidal bones of the tarsus are affected, mild collapse may not adversely affect performance, but with significant collapse, degenerative change is likely. A less common cause of lameness in foals with angular limb deformity is osteochondrosis. The prognosis for athletic performance in foals with osteochondrosis-associated angular limb deformities is guarded, depending on the severity of the cartilage lesions. The importance of early radiographic evaluation of foals with angular deformity cannot be overemphasized. If a diagnosis of incomplete ossification is delayed, irreparable damage may occur. In fact, a strong argument can be made for radiographic evaluation of all foals shortly after birth before uncontrolled exercise is allowed. Radiographic evaluation is mandatory to determine the degree of ossification in premature foals, twins, foals that appear to be relatively immature at birth, and foals born with angular deformities. Radiographic evaluation allows the examiner to identify the origin of the deformity and determine its severity. Dorsopalmar views for the carpus and fetlock using 7 × 17-inch film cassettes and a lateromedial view of the tarsus are recommended. In the carpus and fetlock the origin of the deformity may be subjectively determined by two geometric methods (Fig. 38-6). One is to draw longitudinal lines bisecting the long bones above and below the joint. Where these lines intersect is the pivot point, which is considered the origin of the deformity; the angle of incidence of these lines is an estimation of the degree of deformity. Another method, which we prefer for the carpus and fetlock, is to draw lines through the joints and adjacent physes. These lines should be parallel to each other and perpendicular to the long axis of the long bones proximal and distal to the affected joint. The origin and degree of deformity are estimated by determining where and by what degree these lines deviate from normal. Both asynchronous growth and incomplete ossification can occur concurrently, which is most easily determined with the latter method of geometric evaluation1 (Fig. 38-7). Geometric examination to determine the degree of deformity in the tarsus is less reliable because the tibia and third metatarsus are not in the same frontal plane. The severity of the angular deformity in this location is best determined by a careful visual assessment. Radiographic examination of foals with incomplete ossification reveals a rounded contour to the affected bones instead of their normal angular appearance. The width of the radiolucent cartilage is increased, appearing radiographically as an increase in the width of the joint space (Fig. 38-8). As ossification progresses, the bones may appear wedge shaped or crushed because of deformation of the cartilage during weight bearing. This phenomenon often is noted in the ulnar, fourth, and lateral aspect of the third carpal bones in the forelimb and the central and third tarsal bones in the hindlimb. In severe cases the affected bones may be grossly deformed and appear to be partially extruded from the joint (Fig. 38-9). In the tarsus, lateromedial radiographs are used to determine whether ossification is complete (Fig. 38-10). Radiographic evaluation of foals with angular deformity caused by asynchronous growth may show wedging of the epiphysis (Fig. 38-11), widening of the physis, and sclerosis adjacent to the physis. Geometric evaluation places the deviation in the metaphysis or the epiphysis of the long bone proximal to the affected joint. The joints are parallel to each other and perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the adjacent long bones. Neonatal foals with an angular deformity should be confined to a stall until clinical and radiographic examinations are completed. If the deformity is 10 degrees or less and radiographs reveal normal ossification, stall confinement with periods of controlled exercise is recommended. This regimen promotes continued development of the supporting structures while minimizing trauma to growth cartilages that could result if the foal were allowed uncontrolled exercise. Foals with a congenital angular deformity of more than 10 degrees accompanied by incomplete ossification or ligamentous laxity failing to improve with controlled exercise should be externally supported. If incomplete ossification is present and the limb is not supported in axial alignment, continued weight bearing can cause deformation of the cartilaginous structures. Subsequent ossification results in permanent deformity of the affected bones (see Fig. 38-9). Methods of externally supporting the carpus and tarsus vary from tube casts or rigid splints to custom-made orthotic devices. Tube casts have been recommended and used successfully for several years,1–3 but although they provide the rigid external support required to maintain axial alignment while ossification progresses, several potential complications are associated with their use. The most serious is the potential for coxofemoral luxation when tube casts are used on the hindlimbs. In addition, foal skin is easily traumatized by a poorly fitting cast, and deep ulcerations may occur. Other considerations include the cost of materials and necessity for constant monitoring to detect signs of a poorly fitting cast. Monitoring the status of a cast requires daily evaluation by a trained individual, and owners are seldom capable or willing to take on this responsibility; hospitalization is recommended. Rigid splints are an alternative method of support. The leg is protected with a padded support bandage, and the splint is applied with nonelastic tape while the limb is held in alignment by an assistant. These splint bandages are changed every third or fourth day. Pressure sores beneath the splint bandage are a concern and must be prevented. A splint for the tarsus may be fashioned from synthetic casting material molded lengthwise over the cranial aspect of a padded bandage centered at the joint. Once the material has dried, the splint is taped to the dorsal surface of the bandage. Regardless of the means of external support used for the carpus or tarsus, it should not extend beyond the distal metacarpus or metatarsus. Continued weight bearing by the suspensory apparatus of the fetlock helps prevent development of fetlock hyperextension after removal of the external support. A degree of carpal hyperextension is usually present immediately after removal of external support from the forelimb, and exercise should be controlled until the tendons and periarticular supporting structures regain their normal tone. Foals with an angular deformity resulting from asynchronous growth should also be confined to a stall and allowed only controlled exercise to minimize the magnitude of asymmetric loading at the growth cartilages and encourage spontaneous correction. In these cases, reducing the magnitude of the forces acting asymmetrically at the growth cartilage should encourage compensatory growth to occur and correct the deformity. Additional therapy consists of corrective hoof trimming. Because foals with valgus deformity typically have a toe-out conformation, emphasis in the past has been to lower the lateral hoof wall of the affected limb. If this mode of therapy is vigorously pursued, compensatory varus deformity may develop in the fetlock region. This form of corrective trimming concentrates forces asymmetrically on the medial aspect of the distal metacarpal and proximal phalangeal growth cartilages. Currently, trimming the hoof level and squaring the toe to promote breakover at the toe are recommended. If the lateral hoof wall is to be lowered, only a few millimeters should be removed each week. Foals with angular limb deformities that fail to respond to stall confinement are candidates for surgical therapy. Animals with angular deformities arising distal to the physis were not considered candidates for surgical therapy in the past, but it has been shown that they can respond favorably to surgery.7,8 The decision for surgery should take into account the amount of correction required (degree of deformity) and the age of the foal. The more severe the deformity, the earlier the surgical intervention should be. Timing of surgery should consider the periods of rapid and predictable growth at the physis. The most rapid and predictable rate of growth occurs from birth to 10 weeks of age.9 In the distal radius, continuous but declining growth occurs until 60 weeks of age. In the distal third metacarpal and metatarsal bones, growth rate slows dramatically by 10 weeks of age and stops shortly thereafter. Surgical manipulation of physeal growth is intended to asymmetrically alter the elongation occurring at the physis, thereby realigning the axis of the limb. Growth at the physis can be altered surgically in one of two ways: retardation or acceleration. Growth retardation is accomplished by bridging the physis with metallic implants. When applied to the convex side of the affected physis, growth is disallowed on the long side of the bone while continued growth on the opposite of the bone brings the limb into alignment. As long as the implants are in place, the effect continues and is limited only by the amount of growth remaining at the physis. If the physis is still active once the limb is aligned, it is extremely important that the implants be removed, or overcorrection will occur. Techniques of transphyseal bridging include stapling, screw and wire implants, use of a small bone plate, and more recently, a single transphyseal screw. Indications for transphyseal bridging include deformities that present after the period of rapid and reliable physeal growth, severe angulations, and based on the author’s experience, deformities of the carpus and tarsus resulting from cuboidal bone malformations. In the second surgical approach to altering physeal growth, periosteal transection and elevation (stripping) is aimed at promoting growth acceleration on the concave side of the bone.10 Reported advantages include rapid correction without the potential for overcorrection.7,10 Because periosteal transection does not require implants, the likelihood of infection and excessive fibrosis are reduced. Implant failure is not a consideration, and a second surgery for implant removal is unnecessary. The procedure does not require specialized equipment and is technically easy to perform. In one series of foals, correction of the deformity occurred in 22 of 25 limbs treated with periosteal transection.10 In a second series of 23 foals, 83% had straight limbs and were sound for their intended use at long-term follow-up.7 The success rate was not affected by the origin of the deformity, degree of deviation, or presence of mild to moderate morphologic changes in the involved bones.10 Indications include mild to moderate deformities present during the rapid, reliable growth at the involved physis. The periosteum will reestablish itself, so the surgical effect is short-lived, and if correction is not adequate within 4 to 6 weeks, additional therapy is indicated.

Diseases of the Bones, Joints, and Connective Tissues

Physitis (Epiphysitis)

Definition and Etiology

Clinical Signs

Diagnosis

Treatment and Prognosis

Osteochondrosis

Definition and Etiology

Clinical Signs and Differential Diagnosis

Sites of Predilection

Diagnostic Tests

Pathophysiology

Etiology

Treatment and Prognosis

Angular Limb Deformities

Definition, Etiology, and Clinical Signs

Pathophysiology

Evaluation and Radiographic Findings

Treatment and Prognosis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Diseases of the Bones, Joints, and Connective Tissues

Chapter 38