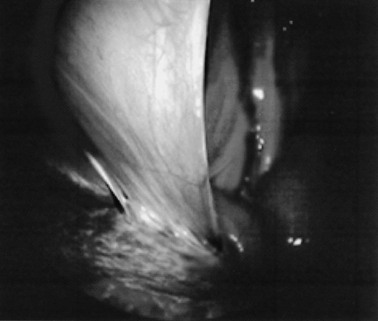

Samuel L. Jones, Bradford P. Smith, Consulting Editors ▪ Diseases of the Equine Alimentary Tract Samuel L. Jones, Consulting Editor Samuel L. Jones A thorough physical examination is compulsory, and tests that provide a minimum database (complete blood count [CBC], serum chemistries, and urinalysis) are often indicated in horses with suspected alimentary tract disease. Once a list of differential diagnoses is compiled, a number of ancillary diagnostic tests are available to narrow the possibilities. Each diagnostic test or procedure is limited in the type and extent of information that can be obtained, and therefore the clinician should select the complement of procedures that is most likely to provide the information required to make a proper diagnosis and determine the appropriate therapy. A systematic approach to examining the abdominal and retroperitoneal viscera should be established and applied during each examination to ensure that all pertinent regions and structures are examined. When feasible and if required, the patient should be sedated to allow a more thorough examination. In some cases, epidural anesthesia is required to obtain adequate access to structures during rectal examination. The principal goal of a rectal examination is to identify changes in size, texture, shape, or location of visceral organs, peritoneum, mesentery, vasculature, or objects that are normally not present. Rectal examination is often performed with ultrasonographic examination, and information derived from each must be considered in order to draw conclusions. Ultrasonographic examination will be described in a later section. In the pelvic region of the normal horse, the urethra and accessory sex glands (male) or the vaginal vault and cervix (female) can be palpated. The urethra is usually not discernible in the female, but abnormalities such as uroliths may be felt. In the caudal abdominal cavity, the bladder, the uterus in females, and the pelvic flexure and small colon typically should be felt. The pelvic flexure and left ventral and left dorsal colons are normally located ventrally, on midline, or toward the left side of the abdomen. The small colon, with formed fecal balls palpable, courses throughout the caudal abdomen, mostly on the left side. In females the left ovary can be felt in the left dorsal, caudal region of the abdomen. Both ovaries should be palpated in conjunction with palpation of the uterus. The peritoneal surface should be felt along the surface of the abdominal wall and the surfaces of the viscera. It should feel smooth, with no crepitus or irregularities. Advancing along the left side of the abdomen, the spleen can be felt as a smooth structure, with the caudal border having a well-delineated, tapered border. The size and location of the spleen are variable, because it can extend from the left body wall to the right ventral region of the abdomen. Advancing cranially and dorsally, the left kidney can be palpated. The kidney should feel smooth with the renal pelvic fissure discernible, although in the overweight horse extensive perirenal fat may obscure this detail. From the left kidney, moving toward midline and extending from the abdominal aorta, the cranial mesenteric and ileocecocolic arteries may be felt. Palpation of fremitus in these arteries may be associated with arteritis and thrombus formation secondary to Strongylus vulgaris larval migration, although this association has been very inconsistent. Fremitus is frequently absent when severe arteritis exists, or the arteries may be entirely normal and fremitus felt. Fremitus can often be elicited by compressing the wall of the normal artery, thus accelerating flow through the compressed lumen. The mesenteric root of the colon can be felt ventral to the cranial mesenteric artery. This should palpate as a mildly taut band of tissue extending from the dorsal midline ventrally. Excessive tension, displacement, thickening, or masses within the mesentery should be considered abnormalities. It may be possible to palpate an enterolith, fecalith, or gravel impaction in the transverse colon, although this may be beyond the reach of the examiner because the transverse colon is located cranial and medial to the left kidney. Sweeping to the right side of the abdomen, the base and cupola of the cecum can be felt. The body of the cecum can be followed partially by sweeping along the medial aspect of the cecum, cranially toward midline. The cecum has a prominent ventral band and sacculations. Gas, together with ingesta that is soft and mainly of a fluid consistency, can be felt within the cecum. Firm or excessive ingesta suggest an abnormality. Findings that are different from normal often must be differentiated as being variations of normal or truly abnormal. Some common abnormal findings include abnormalities of the peritoneal surface. Crepitus, or a “plastic wrap” texture, is indicative of gas secondary to trauma or infection. An irregular or rough surface may be indicative of fibrin on a visceral surface or neoplasia, or with a perforated intestine there may be ingesta adhered to a visceral surface. There are many abnormal presentations of the large colon, most of which are associated with signs of colic. Thickening of the wall of the colon may be appreciated on rectal palpation and is indicative of edema or cellular infiltration of the colon. Palpation of abnormal masses in the wall of the colon or associated with the colonic mesentery is indicative of infection, infarction, granulomatous colitis, or neoplasia. Normally the small intestine is not discerned by palpation. Occasionally, though, peristaltic contractions may be felt in the small intestine as it courses across midline toward the base of the cecum. In some cases this will cause the small bowel to palpate as a firm, tubular structure. Relaxation of the peristaltic contraction should be discerned in such cases. Distention of the small intestine is abnormal. In some cases the bowel may feel thickened, which can occur with ileal muscular hypertrophy, edema, or inflammatory disorders of the small bowel. Other abnormal findings that may accompany disorders of the abdominal alimentary system include masses, adhesions, enlarged and thickened mesenteric arteries, and caudal displacement of the spleen (secondary to gastric distention or neoplasia). Abdominal paracentesis is performed routinely in patients with suspected disorders of the abdominal viscera. Cytologic examination of peritoneal fluid; white blood cell (WBC) and red blood cell (RBC) counts; protein, fibrinogen, lactate, phosphate, and glucose concentrations; lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), creatine kinase (CK), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity; and pH can be quantitated. The results of peritoneal fluid analysis may help establish a specific diagnosis but, more important, may reflect inflammatory, vascular, or ischemic injury to the intestine, requiring surgical intervention. There are two basic types of endoscopic equipment available: equipment based entirely on a fiberoptic system and equipment based on a video chip system. A wide array of affordable endoscopes is now available, and endoscopic examination of the proximal alimentary tract is now common. A typical endoscope found in many private practices is a fiberoptic endoscope that has an insertion tube that is 100 to 110 cm in length and 10 to 14.5 mm in outer diameter. The larger-diameter tube can be inserted only through the nasal passages of older yearlings and adults and is not suitable for alimentary endoscopy, whereas a diameter of 10 mm allows passage through the turbinates of young foals. An insertion tube of 100 cm is sufficient for esophagoscopy in foals up to approximately 3 months of age. For older animals, an insertion tube length of 150 to 180 cm is required for esophagoscopy. An insertion tube length of 110 cm is sufficient to reach the stomach of foals up to 30 to 40 days of age. A length of 150 to 180 cm is required for weanlings, and 200 cm is usually required for yearlings and adults. An insertion tube length of 200 cm is sufficient to reach the stomach of all adults of warm-blooded breeds, although 280 to 300 cm is required to examine the pylorus in adult horses. A 280- to 300-cm-long insertion tube permits duodenoscopy in adult horses. Before a gastroscopic examination, suckling foals up to 20 days of age are not routinely kept from nursing for more than 1 hour. Older foals and mature horses should not have solid feed for 6 to 10 hours so that ingesta from the stomach may be adequately emptied. Longer duration of feed deprivation (12 to 18 hours) is desirable to view the antrum and pylorus of horses. Many foals less than 30 days old do not require sedation for gastroscopy, although sedation with 0.5 mg of xylazine per kilogram may facilitate the procedure. Sedation is required if the foal is to be placed in a recumbent position so that the entire glandular portion of the stomach can be examined. Sedation of older foals and horses is required. Xylazine (0.5 mg/kg given intravenously [IV]) usually provides adequate sedation. For greater sedation, detomidine (0.005 to 0.05 mg/kg IV) or a combination of xylazine and butorphanol (0.01 mg/kg) is effective. After insertion of the endoscope, the stomach is distended with air until the nonglandular and glandular regions of the gastric surface can be observed. Distention with air is tolerated by foals and horses and has been associated only rarely with adverse effects. Occasionally, sick neonates with poor intestinal motility developed small intestinal distention and experienced discomfort after gastroscopy. More complete descriptions of techniques of gastroduodenal endoscopy can be found elsewhere.1,2 Endoscopy of the rectum and distal small colon can be performed with most flexible endoscopes in use in equine practice and should be preceded, as much as possible, by evacuation and saline lavage of the rectum and distal small colon. The mucosal surface should appear pink to pale red and should have a smooth, “velvety” appearance. Mucosal edema or thickening, hyperemia, irregularities, defects, tears, and intraluminal masses are abnormal findings. Because of the concern for trauma to the rectum and small colon, the horse should be adequately sedated and restrained before preparation and examination of the distal alimentary tract. Laparoscopy can offer valuable diagnostic information regarding the abdominal cavity and is only minimally invasive.3,4 It should always be preceded by a thorough physical examination, including abdominal palpation per rectum, and abdominal ultrasonographic examination, paying particular attention to the sites for trocar insertion to ascertain that there are no adherent masses or viscera in the area. If abdominocentesis is to be part of the diagnostic workup, it should be performed before laparoscopy because of the effect of laparoscopy on abdominal fluid values. In experimental animals undergoing diagnostic laparoscopy with carbon dioxide insufflation, both the abdominal WBC count and the abdominal total protein increased.5 The indications for laparoscopy include palpable abdominal masses, enlarged viscera, adhesions, acute or chronic colic, weight loss, or the need to obtain visceral biopsy specimens. Contraindications include adherent viscera or masses at the site of laparoscopic trocar insertion, diaphragmatic hernias, or extreme bloating. Horses with acute colic can be safely examined laparoscopically if one is careful when inserting the trocars and telescopes. The basic instruments for laparoscopic examinations include a laparoscopic telescope, laparoscopic cannula and trocar assembly, fiberoptic light source and cable, insufflator, and biopsy and manipulation instruments. The 30-degree laparoscope allows better visualization of the less accessible areas compared with the 0-degree telescopes. Video cameras make visualization easier with less eyestrain but require more powerful light sources. The cost of laparoscopic instrumentation has decreased recently as a result of the explosion of popularity of laparoscopy in humans, increasing the supply and availability of used instruments. Horses should be fasted for 18 to 24 hours before most laparoscopic procedures; water is allowed on an ad libitum basis. Fasting increases intraabdominal visualization and decreases the possibility of penetrating a gas-distended viscus. The animal is restrained in standing stocks if the procedure is to be done while it is standing. Preoperative antibiotics, antiinflammatory drugs, tetanus prophylaxis, and a sedative analgesic combination are administered. It is important to administer the analgesics before abdominal insufflation. The flank areas are prepared for aseptic surgery. Local anesthetic agents are infiltrated subcutaneously (SC) and intramuscularly (IM) in the middle of the paralumbar fossa slightly above the crus of the internal abdominal oblique muscle for the insertion of the laparoscopic telescope. If additional instruments are to be used, their insertion sites are similarly anesthetized. It is preferable to begin the laparoscopic procedure on the left side of the abdomen to minimize the chance of penetrating the cecal base. The horse is then draped and a stab incision is made. The laparoscopic cannula and trocar assembly are inserted through the musculature and into the abdominal cavity. It is useful to orient the trocar toward the opposite coxofemoral joint when inserting it. The trocar is exchanged for the telescope, and confirmation of entry into the abdominal cavity is made before insufflation is commenced. If the abdominal cavity has not been penetrated, a quick thrust with the telescope will usually penetrate the peritoneum. Insufflation of the abdomen with CO2 to 8 to 10 mm Hg will usually be sufficient for most examinations. Systematic examination of the abdominal cavity is then carried out. On the left side of the abdomen, the spleen, left kidney, nephrosplenic ligament (Fig. 32-1), stomach, left side of liver, diaphragm, and ventral colon may be visualized cranially. Looking caudally, the examiner will see the root of the mesentery, the isolated small intestinal and small and large colon sections, the urogenital tract, the bladder, and the terminal rectum. The procedure is repeated on the right side of the abdomen. Looking cranially, the examiner will see the liver, epiploic foramen, right kidney, descending duodenum, cecal base, and large colon. Caudally, the urogenital tract, root of mesentery, and isolated pieces of intestine are visible. Liver biopsies and right kidney biopsies are taken from the right side. Left kidney and spleen biopsies are taken from the left side of the abdomen. Mesenteric lymph node biopsies are usually obtained via the left flank. Other masses are biopsied from the more accessible side. At the end of the procedure the abdomen is deflated, and the skin is closed with skin sutures only. Closure of the skin incision should wait until examination of both sides is completed in order to minimize subcutaneous emphysema. In some horses with ventral or cranial abdominal masses as determined with ultrasound, it is useful to anesthetize the animal in dorsal recumbency for better characterization of the mass. Biopsies may be readily obtained. In horses with acute colic but without obvious signs indicating the necessity for surgery, laparoscopy can help in making the decision to continue medical therapy or proceed to surgery. Strangulated sections of small intestine can be seen, proximal enteritis can be diagnosed, and edema and vascular compromise to the large colon can be seen. No abnormalities may be detected in some animals with very localized lesions, or lesions may be inaccessible, depending on location. Laparoscopic complications are similar to those of any other abdominal exploratory procedure. Inadvertent penetration of a viscus may occur. The left kidney may be perforated if the laparoscope is inserted too far dorsally. The spleen may be penetrated if the laparoscope is inserted too far ventrally or is not aimed toward the opposite coxofemoral joint. The cecum may be perforated when entering from the right side. Fasting the horses and carefully inserting the laparoscopic trocars will minimize the occurrence of these problems. Subcutaneous emphysema occurs commonly but has not caused any clinical problems. The peripheral WBC count increased but stayed within normal limits in experimental animals undergoing laparoscopy.5 Michelle Henry Barton One of the most innovative, practical, affordable, and portable diagnostic tools introduced into the field of equine internal medicine in the past two decades is transcutaneous ultrasonography. Although several different types of ultrasound transducers exist, adult equine abdomens are most completely imaged using a 2- to 5-MHz curvilinear array transducer, although a high-frequency (6- to 8.5-MHz) linear array transducer can be used to optimize resolution of superficial intraabdominal structures. Ideally, before getting started, the patient’s hair should be clipped, the skin cleaned, and coupling gel applied. If clipping the hair is not an option, removing debris with grooming aids and soaking the hair with isopropyl alcohol will often suffice. Most horses tolerate transabdominal ultrasonography without sedation. In patients sedated with α2-adrenergic agonists, small intestinal and cecal motility can be transiently reduced, especially in fasted horses, and the luminal diameter of the small intestine may appear more dilated than in unsedated patients.6,7 Detailed review of the physics of ultrasonography is beyond the scope of this section; however, there are several general principles that should be kept in mind when transabdominal ultrasonography is performed. First, to ensure that all structures are properly assessed, it is essential to have a consistent and systemic approach for covering the entire area to be evaluated—for example, scanning one side at a time, dorsal to ventral, cranial to caudal. Using seven discrete locations in horses being evaluated for acute abdominal pain, the FLASH (fast localized abdominal sonography) method can be completed in less than 15 minutes and is highly effective in correctly assisting diagnosis.8 The seven locations evaluated in the FLASH method are ventral, gastric, splenorenal, left middle third of the abdomen, duodenal, right middle third, and thoracic. Next, being mindful of the position of the transducer and its orientation marker on the patient relative to the “default” method for display of the image on the monitor greatly facilitates correct orientation to the anatomy being imaged (Fig. 32-2). Because abdominal ultrasonography is often performed with the footprint of the transducer in an intercostal space, most imaging of the abdomen is performed with the transducer oriented in a slightly oblique transverse plane (i.e., slicing across the long axis of the body). Careful attention should be paid to the spatial relationship of the viscera because this may be the only key feature distinguishing normal from abnormal.9 Furthermore, the walls of some sections of the gastrointestinal tract appear strikingly similar and cannot be distinguishable unless information is provided about the probe’s exact location on the patient.10 Third, in any ultrasonographic examination, it is important to be aware of the depth of the field of view. Selecting the appropriate frequency for the transducer is the key to producing high-quality images that are suitable for the depth of display. High-frequency probes provide sharp images, but the resolution is compromised as the depth of the viewing field increases. A final general and helpful principle of ultrasonography is that more sound waves reflect to the transducer if two adjacent interfaces have markedly different acoustic impedances. The more sound that reflects to the transducer, the “whiter” the interface appears on the monitor; these tissue interfaces are called echogenic or hyperechoic. In contrast, less dense tissues reflect less sound, appear darker, and are referred to as anechoic or hypoechoic structures. The soft tissue of the walls of the gastrointestinal tract have an acoustic impedance that is several thousand-fold greater than that of the free gas inside the adjacent lumen.11 Consequently, the image at this soft tissue–to-gas interface appears as a fuzzy hyperechoic border (see Fig. 32-2). Because most of the sound waves at this interface are reflected and the free gas in the lumen has extremely low impedance, the rest of the lumen is obscure as sound is neither penetrating nor reflecting from the lumen. Gas within a large luminal viscus is one of the greatest limitations to gastrointestinal ultrasonography in the horse, as it impedes visualization of deeper structures. While imaging a patient, the ultrasonographer should remember that gas rises to the nondependent portion of the abdomen and fluid and heavier structures fall to the dependent locations. When using a 3.5- to 5-MHz curvilinear transducer, identification of the anatomic layers of the intestinal wall in healthy horses is less distinct, with the wall typically appearing as a single hyperechoic line. Depending on the surrounding tissue and the contents of the lumen, three to five layers of the gastrointestinal wall may be visible when a high-frequency transducer is used; these five layers are the hyperechoic serosa, hypoechoic muscularis, hyperechoic submucosa, hypoechoic mucosa, and the hyperechoic mucosal interface with the lumen (Fig. 32-3).12 In the following sections, transabdominal ultrasonography of the gastrointestinal tract will be reviewed with a systematic approach of scanning the left side of the abdominal cavity, cranial to caudal, followed by scanning the right side of the abdominal cavity. For the gastrointestinal tract, the ultrasonographer should be careful to document the following key elements: motility, presence of luminal distention, wall thickness and morphology, luminal contents, and viscera position. When imaging is started on the left rostral side of the abdomen, the stomach should be located deep to the spleen between the ninth and thirteenth intercostal spaces at approximately the level of the shoulder. In this location, the only part of the stomach that can usually be seen is the wall of the greater curvature, which can be reliably identified as a smooth curved hyperechoic line adjacent to the spleen and the splenic vein (see Fig. 32-2).13 The motility of the stomach is sluggish and the ultrasonographer may get the impression that the greater curvature of the stomach remains stationary.7 The stomach has the thickest wall in the gastrointestinal tract, measuring approximately 7 mm thick from the serosal layer to the mucosal-luminal interface.14 When the stomach is empty, the wall measures up to 1 cm thick, ill-defined loops of small intestine may appear between the stomach and the spleen, gastric rugal folds may be visible, and the gastric wall may be found only below the costochondral junction.7,14 Gastric Impaction and Ulceration. Because only the dorsal portion of the greater curvature can be seen and the lumen generally contains gas at this location, transcutaneous ultrasonography of the stomach is not a sensitive diagnostic tool for gastric ulceration, intramural gastric masses, or gastric impaction. However, if the wall of the greater curvature of the stomach extends beyond the fourteenth intercostal space in a horse that has not recently drunk or eaten, gastric distention should be suspected.15 Furthermore, if excessive gastric fluid is present ventrally, a distinct hyperechoic gas–fluid interface may be apparent in the lumen (Fig. 32-4). If the stomach wall appears irregular or thickened, follow-up gastroscopy is indicated for a more definitive diagnosis (see Fig. 32-3). Although the focus of this section is gastrointestinal ultrasonography, the proximity of the spleen and left kidney to the gastrointestinal tract warrants brief review. Caudad from the stomach, the spleen should be identifiable immediately adjacent to the body wall, from the left ventral eighth intercostal space to the paralumbar fossa. The size and location of the spleen vary greatly: the spleen can be left of the midline or extend slightly right of the ventral midline. In the rostral ventral left abdomen of some horses, the most rostral aspect of the spleen can be seen either lateral or medial to the liver.9 The spleen’s ultrasonographic architecture is usually homogeneous, with vessels that are rarely visible. The echogenicity of the spleen is greater than that of the liver or kidneys. The left kidney can be found between the fifteenth and seventeenth intercostal spaces and the first to third lumbar vertebrae, medial or deep to the spleen (Fig. 32-5), between the level of the tuber coxae and the tuber ischii.16,17 Rarely, the left kidney can directly appose the left body wall.9 Gas in the small colon, left colon, or lung can normally preclude transabdominal viewing of the left kidney, though colonic gas obscuring visualization of the left kidney may be adjunct evidence of dorsal displacement of the left colon.18 The ultrasonographic dimensions of the left kidney vary according to the location from which the measurements are obtained. The longitudinal axis for craniocaudal length (i.e., the dorsal plane parallel to the spine) is difficult to measure because of interference by the ribs.17 In Thoroughbred horses, the length of the left kidney varies from 9.6 to 15.6 cm.16 The dorsoventral height in the slightly oblique transverse plane varies from 3.1 to 8.1 cm and the lateromedial thickness varies from 6.6 to 9.1 cm.16 The corticomedullary junction should be distinct, with the cortex being more echogenic. The adrenal glands are not usually identifiable via transabdominal ultrasonography.9 Many disorders of the large colon can be palpable by rectal examination, and thus transabdominal ultrasonography is an ancillary tool. Ventromedial to the spleen, the left ventral colon can be identified by its sacculated wall (Fig. 32-6) and sluggish but visible motility, normally contracting two to six times per minute.7,10,12 Precise measurement of the colonic wall can be difficult because of the indistinct mucosal-luminal interface; in general, however, the wall of the colon should measure less than 4 mm.10,12,14 The left dorsal colon is not sacculated and can be located dorsal, lateral, medial, or even ventral to the left ventral colon. Gas in the left ventral colon often precludes distinct identification of the left dorsal colon when the latter lies medial or dorsal to the left ventral colon. Gas in the colon typically generates a hyperechoic wall with an indistinct luminal border and intraluminal acoustic shadowing that precludes identification of the contents and the medial walls. Colitis. When visualized through ultrasonographic exam of the left colon, wall thickness and morphology, orientation of the colon, and its contents, are useful diagnostic characteristics. For example, thickening of colon wall can be caused by inflammation, infiltration by neoplastic cells, hemorrhage, or edema. Inflammation of the colon wall (i.e., colitis) can result in mural widening, but the mucosal border often appears shredded, undulating, or wavy (Fig. 32-7). These later findings may be particularly helpful in identifying horses in the prodromal phase of colitis, prior to the onset of diarrhea. The contents of the colon can change from characteristic acoustic shadowing to that of swirling mixed echogenic fluid that may enable visualization of the distal colonic wall. With colitis, colon motility can be increased, decreased, or remain unaffected. Colon Volvulus. Colonic edema resulting from a volvulus of the colon will also result in uniform hypoechoic mural thickening that is best identified with imaging along the ventral midline behind the xyphoid. In one study that evaluated colon wall edema by transcutaneous ultrasonography using a ventral abdominal window, a colon wall thicker than 9 mm had a sensitivity of 67% and specificity of 100% for colon volvulus.19 In addition, in some cases of colonic volvulus, nonsacculated colon replaces sacculated colon in the left ventral abdomen.20 Furthermore, the blood supply to the ascending colon is located in the mesentery along its medial aspect, and thus there are normally no major blood vessels visible ultrasonographically on the lateral surface (adjacent to the body wall) of the ascending colon. The ultrasonographic finding of distended vessels with reduced blood flow in colonic mesentery adjacent to the body wall implies that the colon is rotated along its long axis and would be consistent with a diagnosis of displaced colon or a colon volvulus.21 Colonic motility would be reduced with a volvulus. Left Colon Displacement. On the left side of the abdomen, dorsal displacement of the left colon over the nephrosplenic ligament may obscure ultrasonographic visualization of the dorsal aspect of the spleen or left kidney, or the colon may appear lateral to the spleen (Fig. 32-8).18 However, if gas is not present in the entrapped colon, the ultrasonographic diagnosis can be missed. Likewise, gas within the left colon can obscure the left kidney without the colon being entrapped. When ultrasonographic and other clinical findings support the diagnosis of left dorsal displacement of the colon, serial ultrasonography of the area can be a useful noninvasive method to determine if the colon has relocated to its ventral position upon successful ultrasonographic visualization of the left kidney. Colon Impaction. Gas within the colon often precludes accurate ultrasonographic diagnosis of colonic impaction. An impaction should be suspected in the ventral colon by the presence of a hyperechoic border at the mucosal surface that casts a strong acoustic shadow and flattened sacculations. Sand impactions are best seen in the ventral abdomen and often compress the mucosal surface, create excessive acoustic shadowing or reverberation artifacts (Fig. 32-9), and significantly reduce visible motility of sacculations.22 The small colon is located in the left paralumbar fossa medial or ventral to the spleen. Because of its small diameter, sacculations, and packed serpentine loops that suspend from the dorsal mesocolon, often only small sections of the surfaces are visible ultrasonographically as short, sharply curving, hyperechoic lines (Fig. 32-10). As with the large colon, the motility of the small colon is slow (no more than 3 contractions per minute) and luminal surface gas typically prevents visualization of the contents and the distal walls.12 Likewise, the dense content of fecal balls in the small colon often generate anechoic shadows from the near wall that precludes visualization of the distal wall (see Fig. 32-10). Small Colon Impaction. Impactions or enteroliths obstructing the lumen of the small colon can usually be readily diagnosed by transrectal examination; however, transabdominal ultrasonography may reveal loss of, or enlargement of, sacculations and intense anechoic shadowing (Fig. 32-11). In fed healthy horses, the jejunum can only be identified in approximately 10% of horses.7 One must carefully watch for peristaltic activity that creates transient expansion of the lumen from movement of ingesta. The medial location of the ileum precludes distinct identification by transcutaneous ultrasonography. The jejunum is most consistently found in the left inguinal area, medial to the spleen and the left ventral colon (Fig. 32-12). The small intestine has the most visible motility of any part of the gastrointestinal tract, with peristaltic waves producing frequent rhythmic contractions. Fluid luminal contents typically enable accurate measurement of the wall (<3 mm) and visualization of the far wall along its long or short axis.14 In healthy horses, jejunal luminal diameters rarely exceed 3 cm.14 Following complete contraction with peristalsis, a distinct lumen becomes difficult to discern. Fasting and/or sedation with an α2-adrenergic agonist decreases motility of the small intestine, thereby significantly increasing the likelihood of visualization.6,7 Distended Loops of the Small Intestine. Distended loops of small intestine often look the same on ultrasound, despite the underlying cause. Recalling that normal duodenum and jejunum are difficult to visualize in healthy fed horses, if the small intestine is found easily by ultrasonographic exam, the luminal diameter of small intestine exceeds 3 cm, or peristaltic contractions are notably reduced, it should be considered abnormal. Small intestinal distention can result from paralytic causes, in which there is reduced motility without physical luminal blockage or from mechanical reasons, in which there is a distal luminal or extraluminal obstruction impeding peristalsis. With either paralytic or mechanical ileus, small intestinal distention can progress to the point where the dilated segments of small intestine must fold back on themselves, creating the appearance of turns or curves within the lumen when caught in long axis (Fig. 32-13). As ileus progresses, denser ingesta will settle to the dependent portion of the affected segments (Fig. 32-14). In general, if small intestinal distention progressively increases and motility decreases over serial examination, mechanical causes of obstruction that require surgical intervention should be considered.23,24 Scrutiny of the patient’s clinical signs, ancillary diagnostic findings, and some distinguishing ultrasonographic features can be helpful in discriminating paralytic versus mechanical causes of small intestinal distention. In particular, the ultrasonographer should pay close attention to the small intestinal wall thicknesses and morphology, progression of distention, degree of motility, and appearance of the intestinal contents. Acute Enteritis. The wall of the small intestine can be thicker than normal (i.e., >3 mm) from inflammation, edema, hypertrophy, or neoplasia. Some causes of inflammation and edema are acute in nature, such as proximal or anterior enteritis, and some causes are chronic or insidious in nature, such as the inflammatory bowel syndromes or idiopathic intestinal hypertrophy. In addition to the clinical signs and other diagnostic features of proximal enteritis (low-grade fever, gastric reflux, inflammatory leukogram, pain followed by depression after gastric decompression), on ultrasonographic exam, the mucosal wall of the small intestine may appear shredded, 14 corrugated, or wavy, resembling the edge of a lasagna noodle (Fig. 32-15). The proximal portions of the small intestine, especially the duodenum (see duodenum section below; Fig. 32-16), and the stomach may be distended with fluid. The motility of these loops can vary from low to apparently no movement to hypermotile. For horses with enteritis, the expected response to medical therapy varies, but lessening degrees of luminal distention with progressive improvement in motility are expected. If hyperechoic gas sounds are seen within the wall of the small intestine, it is indicative of either necrosis or anaerobic bacterial infection. Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Ileal Hypertrophy. If the signs of abdominal pain are more insidious, if there is weight loss despite a good appetite, or if panhypoproteinemia is present, symmetrically and diffusely or regionally thickened small intestine may be a sign of infiltrative or hypertrophic disease, such as inflammatory bowel disease, neoplasia (especially lymphosarcoma), or idiopathic ileal hypertrophy.25 In these circumstances, the wall can be either uniformly or irregularly thickened, often with a narrow or obscure lumen (Fig. 32-17). Motility is usually preserved, unless mural thickening results in secondary mechanical obstruction. Definitive diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease or idiopathic hypertrophy requires histopathologic evaluation. Nonstrangulating Obstructive Lesions of the Small Intestine. Mechanical obstruction of the small intestine in which the adjacent blood supply remains intact, such as an ileal impaction, adhesions, mural hematoma, or severe chronic infiltrative disease of the intestinal wall, would be expected to cause variable degrees of luminal distention proximal to the site of obstruction. In general, lack of significant changes in wall thickness or morphology would be helpful features for distinguishing simple nonstrangulating lesions of the small intestine from strangulating or severe inflammatory lesions. If serial ultrasonography reveals progressive severity of distention and lack of motility (see Fig. 32-17), surgical intervention should be considered.23,24 Strangulating Obstructive Lesions of the Small Intestine. Progressive pain with poor response to medical intervention, lack of fever, and serosanguineous peritoneal fluid with increased or increasing lactate concentrations are clinical features that might help distinguish strangulating lesions of the small intestine from simple obstructions and enteritis. As with nonstrangulating obstructive lesions of the small intestine, ultrasonographically, the intestine proximal to strangulating obstructions will be distended with either gas or fluid. The degree of distention and motility will vary with the duration of strangulation, although the presence of progressive distention of preobstruction segments to turgidly circular and completely amotile loops of small intestine is highly correlated with mechanically obstructive lesions that require surgical intervention (Fig. 32-18).23,24 An important distinguishing feature of strangulated small intestine is the appearance of focally and usually uniformly thickened walls at the site of the strangulation (Fig. 32-19). Thus, when regional uniformly thickened small intestine is identified ultrasonographically, with other evidence of obstruction (hypomotile, hairpin turn stacks of turgidly round and distended loops of small intestine with dependent ingesta), a strangulating obstruction should be the top consideration. Frequently the strangulated loops are identified in the ventral portions of the abdomen. In one study, focally thickening and distended small intestine with no motility was 100% sensitive and 100% specific evidence for strangulating lesions of the small intestine.23 If the affected segments are most readily visualized adjacent to the spleen and stomach on the left side of the abdomen (Fig. 32-20) or between the liver and right dorsal colon on the right side of the abdomen (Fig. 32-21), these respective locations are areas in which gastrosplenic and epiploic foramen incarcerations are readily found. Intussusception. Finally, intussusceptions of the small intestine are most common in foals and young horses and have a characteristic “bull’s-eye” or target lesion appearance of the affected segments when imaged across the short axis of the small intestine (Fig. 32-22).26 The intussuscepted intestine tends to fall toward the dependent portion of the abdomen. Like other mechanical obstructive diseases, the proximal small intestine will have normal wall thickness but will be distended, with reduced motility and hairpin turns, depending on the degree of obstruction. The liver, descending duodenum, and right dorsal colon have characteristic proximity of location and can be identified in the right rostral abdomen at the level of the shoulder (Fig. 32-23). The liver is located from the sixth to the fourteenth intercostal spaces between the diaphragm and the right dorsal colon (see Fig. 32-23). Gas in the lung or the right dorsal colon can obscure identification of the liver dorsally and ventrally, respectively; thus ultrasonographically, the liver may only be visible over a few intercostal spaces. Only a small portion of the right side of the liver can be imaged, so its size is estimated based on its expanse across the intercostal spaces.9 It is unusual for the liver to be seen beyond the fifteenth intercostal space or in the same transverse plane as the right kidney, except at the most rostral aspect of the kidney. The ventral edges of a normal liver are distinctly sharp. As with the spleen, the architecture of the liver is relatively homogeneous, but more vessels are visible in the liver and the general echogenicity of the liver is less than that of the spleen.14 Portal veins have more connective tissue in their walls and thus have more echogenic walls than the hepatic veins.9 Short segments of smaller portal veins often appear as hyperechoic parallel lines (see Fig. 32-23). In some small horses, the portal vein can be seen entering the hilus deep on the medial side of the image. The common bile duct and its branches within the liver are not normally visible.9 The pancreas is not usually identifiable via transabdominal ultrasonography.9 The position of the duodenum is fixed by its suspending mesoduodenum; thus the duodenum can reliably be found descending the right middle abdomen at approximately the level of the shoulder and is located between the liver and the right dorsal colon (see Fig. 32-23), where it can be imaged transversely along its short axis. As with the jejunum, to locate the descending duodenum, the ultrasonographer must wait for a peristaltic contraction to deliver ingesta through the lumen, thereby expanding the lumen. Otherwise, the duodenum typically appears as a hyperechoic flattened or crescent-shaped line to flattened oval shape. It is unusual for the duodenal diameter to exceed approximately 3 cm in healthy horses during peristaltic propulsion of ingesta.27 The duodenum contracts one to four times per minute in fed horses,27 but contractions are less frequent in anorectic, fasted, or heavily sedated horses. The duodenum can be followed to the level of the ventral right kidney (Fig. 32-24), where it crosses medially into the abdomen and is no longer distinguishable. The wall of the duodenum is less than 3 mm thick.14 The right dorsal colon, which has no sacculations, is immediately ventral to the liver and duodenum and is usually found from the right tenth to twelfth intercostal space, although it can extend to the fourteenth intercostal space.28 The wall of the right dorsal colon consistently appears as a hyperechoic curved line, adjacent to the liver (see Fig. 32-23), that measures less than 4 mm, although a range up to 5.9 mm has been reported in healthy horses.28 If the ultrasonographer locates the right dorsal colon and slides the transducer ventrally, the interface between the right dorsal and right ventral colon is often identifiable as what appears to be an indentation in the wall between the nonsacculated right dorsal colon dorsally and the sacculated right ventral colon ventrally. The right ventral colon has sacculations, and its contractions and wall thickness are similar to those of the left colon, although a wall thickness up to 5.1 mm has been reported in healthy horses.28 The contents of the right colons and their medial walls are normally obscured by luminal gas. The transverse colon is not usually identifiable via transabdominal ultrasonography.9 Right Dorsal Colitis. When diarrhea in a horse is accompanied by panhypoproteinemia and a history of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) use, transabdominal ultrasonography of the right dorsal colon can be a useful diagnostic aide.28 In patients with NSAID-induced right dorsal colitis, the wall of the right dorsal colon will often appear thickened with mixed echogenicity and an irregular mucosal-luminal interface. Right Dorsal Colon Displacement. Identification of a large gas-distended viscus in the right caudal abdomen by transrectal palpation with accompanying taut colonic bands is consistent with a diagnosis of right dorsal displacement of the colon. The only major blood vessels normally visible ultrasonographically in the right caudal abdomen are those associated with mesentery of the lateral cecal band.12 Thus the ultrasonographic finding of distended vessels with reduced blood flow in colonic mesentery adjacent to the body wall implies that the colon is rotated along its long axis and would be consistent with a diagnosis of right dorsally displaced colon or a colon volvulus (Fig. 32-25).21 The cecum has a sacculated wall that extends from the right paralumbar fossa to ventral midline and has motility that is similar to that of the colons.7,12 A unique characteristic that can be useful to distinguish the cecum from the right ventral colon is that the lateral cecal band is oriented dorsoventrally and contains an associated artery and vein, whereas the lateroventral band of the right ventral colon is oriented caudocranially and does not have associated vasculature.12 The cecal wall is less than 4 mm thick, and gas in the lumen precludes imaging the contents and far wall. Most diseases affecting the cecum can be sufficiently identified by transrectal palpation; however, transcutaneous ultrasonography can be helpful in confirmation of the diagnosis. Typhlitis. With acute inflammatory disease of the cecum, the wall may be thickened, the mucosal surface may appear irregular or wavy, and motility will vary from hypomotile to hypermotile. Gas normally present in the body or base of the cecum precludes visualization of its contents and distal wall; however, with typhlitis, the cecum is often distended with fluid that is readily seen swirling inside of the lumen and can enable visualization of the distal wall, especially toward the cecal apex. Cecal Impaction. Transrectal palpation is a better method to diagnose cecal impactions, but transabdominal ultrasonography of cecal impactions may reveal loss of characteristic sacculations. Cecocolic and Cecocecal Intussusception. Intussusceptions involving the cecum are often palpable on transrectal evaluation as indistinct large, firm masses in the right or mid caudal abdomen. Like small intestinal intussusceptions, the characteristic “target lesion” of the wall of the cecal apex or body within the lumen of the cecum or right ventral colon can be seen. In chronic intussusceptions, the walls are very thick and may appear abscessed or mass-like (Fig. 32-26). Gas in the cecum, right dorsal colon, or lungs sometimes obscures visualization of the right kidney, which can normally be found in the rostral fifteenth to seventeenth intercostal space17 (see Fig. 32-24). In Thoroughbred horses, the right kidney is 6.5 to 9.1 cm dorsoventrally (the slightly oblique transverse plane), 12.1 to 16.2 cm in length craniocaudally (the dorsal plane), and 6.5 to 8.4 cm lateromedially.16 The ureters are usually difficult to identify, but the proximal right ureter sometimes appears as a hyperechoic circular structure at the hilus. The architecture of the right kidney is similar to that of the left kidney. In the healthy horse, only minute pockets of peritoneal fluid should be identifiable in the rostroventral area of the abdominal cavity or adjacent to sacculations of the ventral colons. The abnormal presence of excessive peritoneal fluid displaces organs and greatly facilitates visualization of structures not normally seen on ultrasonographic exam, such as the mesentery of the small intestine (Fig. 32-27). Peritonitis should be suspected if there is increased volume or echogenicity of peritoneal fluid. In some cases, free-floating or adherent fibrin or fibrous tags may be visible (Fig. 32-28). An abdominocentesis would be an integral step to further characterize the etiology of peritonitis. Excessive blood in the peritoneal cavity will displace organs off the body wall. Blood in the peritoneal cavity appears as a mixed echogenic fluid that, in real time, often appears to “swirl” as it mixes with less echogenic peritoneal fluid (Fig. 32-29).12 Abdominocentesis will confirm the presence of blood. Abscessation, hematoma, and neoplasia are the top differential diagnoses for intraabdominal space-occupying lesions, each of which can be located just about anywhere in the peritoneal cavity, in or attached to bowel, other intraabdominal viscera (i.e., spleen, kidney, liver), or the peritoneum. Space-occupying lesions appear as soft tissue densities of variable shapes and acoustic properties that distort normal sonographic architecture (Fig. 32-30). Although the definitive cause of an intraabdominal mass is often not discernible ultrasonographically, both abscesses and hematomas appear as either uniform echogenic or loculated space-occupying masses of mixed echogenicity. Chronic abscesses may be characterized by the presence of a thick echogenic capsule. An abscess or hematoma more commonly is isolated to a single location, whereas metastatic neoplasia should be considered if variable sized space-occupying lesions that distort normal ultrasonographic anatomy are present in multiple locations. Although the ultrasonographic appearance of a space-occupying lesion may not help determine the cause, ultrasonography can be a useful guide to biopsy or aspiration of the affected tissue.

Diseases of the Alimentary Tract

Diagnostic Procedures in the Examination of the Equine Alimentary System

Rectal Examination

Paracentesis

Endoscopy

Laparoscopy

Transcutaneous Ultrasonography of the Mature Equine Alimentary Tract

Technique

Ultrasonography of the Left Side of the Abdomen

Stomach.

Spleen and Left Kidney.

Left Colons.

Small Colon.

Small Intestine.

Ultrasonographic Anatomy of the Right Side of the Abdomen

Liver and Pancreas.

Duodenum.

Right Colons.

Cecum.

Right Kidney.

Peritoneal Cavity.

Peritonitis.

Hemoabdomen.

Intraabdominal Masses.

Diseases of the Alimentary Tract

Chapter 32

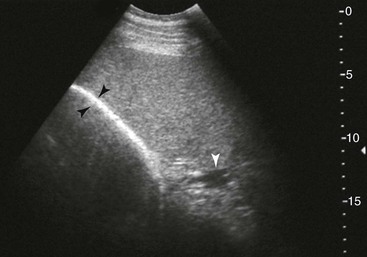

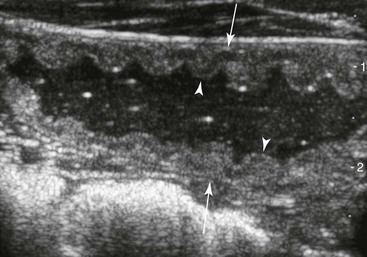

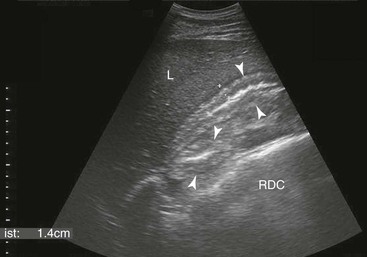

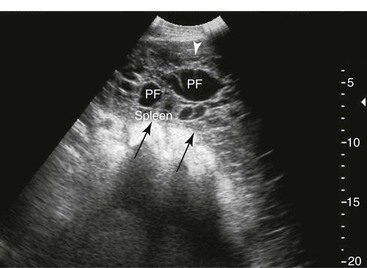

FIG. 32-7 This image was obtained from the same location as Fig. 32-6 from a patient with colitis. The left ventral colon is identifiable by its location medial to the spleen and by its sacculations. The wall of the colon was thickened to approximately 1 cm with three distinct layers: hyperechoic serosa (white arrowhead), hypoechoic muscularis, and submucosal, hyperechoic mucosal-luminal interface (white arrow). This image was obtained with a 3.5-MHz curvilinear probe set to a depth of 11 cm. Left is dorsal.

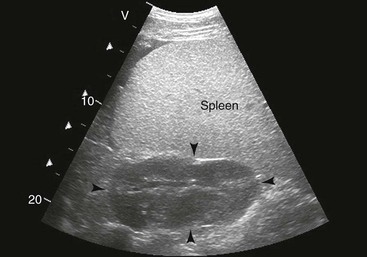

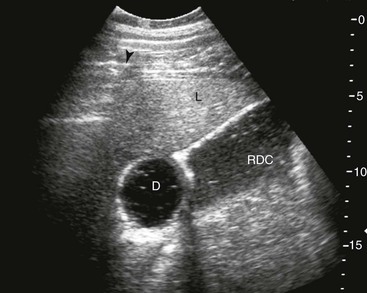

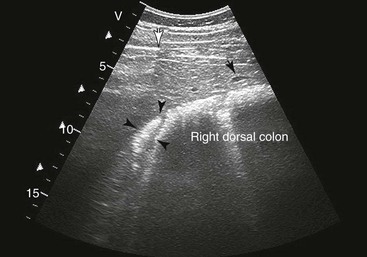

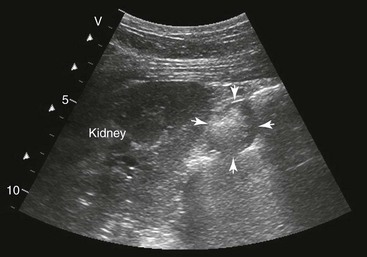

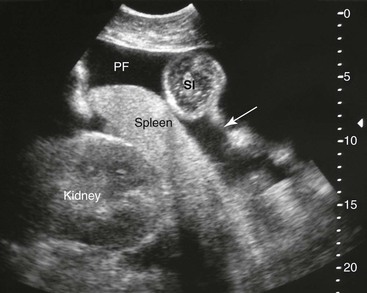

FIG. 32-8 This image was obtained from the same location as Fig. 32-5 using a 3.5-MHz curvilinear probe set to a depth of 20 cm. This horse had a left dorsal displacement of the colon into the renosplenic space. The gas-distended colon (arrows) obscures visualization of the left kidney. (Courtesy Science In 3D, Inc. and © 2002—University of Georgia Research Foundation, Inc.)

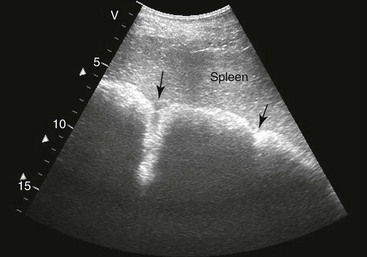

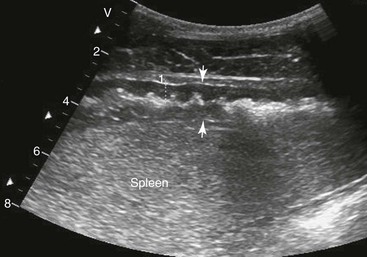

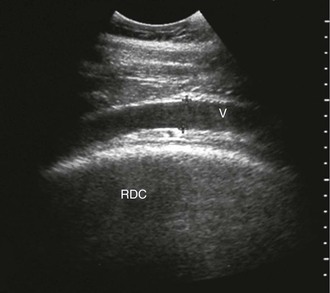

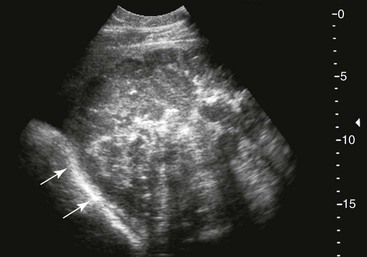

FIG. 32-9 This image was obtained from the same location as Fig. 32-23 using a 3.5-MHz curvilinear probe set to a depth of 13 cm. The left side of the image is dorsal. Sand and gravel in the dependent portion of the right dorsal colon (white arrowheads on serosal surface) create reverberation artifacts in the lumen. The colon wall is thickened. (Courtesy Science In 3D, Inc. and © 2002—University of Georgia Research Foundation, Inc.)