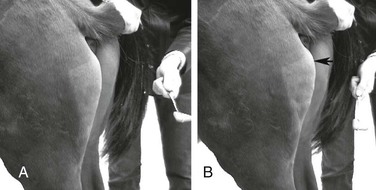

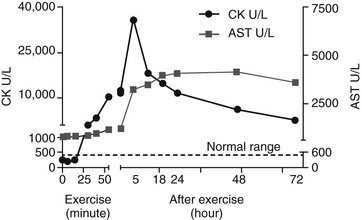

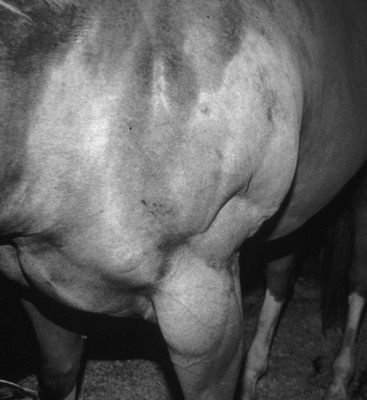

Stephanie J. Valberg, Consulting Editor Stephanie J. Valberg Clinical evaluation of the muscular system requires a systematic and routine method for examination. Often a veterinarian is asked to examine an animal with a history of a relatively nonspecific disease process that may be the result of muscular dysfunction. Animals with electrolyte imbalances, pleuritis, colic, chronic wasting diseases, poor performance, weakness, and a number of lameness problems may initially have signs similar to those seen with some forms of muscular dysfunction. A thorough history of the animal or animals involved is an integral part of characterizing the muscle disorder, particularly because many disorders are intermittent in nature and triggered by certain environmental stimuli. A careful description of the animal’s muscle tone, muscle mass, gait, degree of pain, exercise intolerance, and weakness while experiencing clinical signs should be obtained. In addition, the duration of illness, intermittency of clinical signs, factors precipitating clinical signs, exercise schedule, diet, current medications, vaccination history, and number of other animals affected and their familial relationships should all be recorded before the muscular system is examined. Initially the animal can be observed from all aspects at a distance while the horse is standing with forelimbs and hindlimbs exactly square. The examiner should observe the size, shape, and symmetry of all muscle groups and look for muscle fasciculations. This observation helps provide impressions about tropic changes, alterations in symmetry of particular muscle groups, and spontaneous muscle activity. The animal can then be walked, trotted, or driven and evaluated for gait abnormalities. The symmetry of the gait and evidence of lameness, weakness, stiffness, and pain associated with movement can be noted. Gait abnormalities may result from pain, muscle weakness, muscle cramping, spasticity, decreased range of joint motion, dysfunction of motor neurons, and ataxia. Following initial visual evaluation, muscles should be palpated to obtain an overall impression of muscle tone, consistency, sensitivity, swelling, atrophy, and heat. Firm, deep palpation of the lumbar, gluteal, and semimembranosus and semitendinosus muscles may reveal pain, cramps, or fibrosis. Comparisons between muscle groups and areas of the animal can then be made to identify atrophy or swelling. Some animals are tense and demonstrate apparent evidence of myalgia when palpation is first performed. However, given time and patience, many of these animals relax, and muscles or muscle groups that at first examination appeared to be very sensitive or hypertonic may in reality be normal. By this stage it can often be determined whether individual muscles, muscle groups, a limb or limbs, or the whole body musculature is involved. The symmetry or absence of symmetry of affected muscles or muscle groups is also important. Horses should stand perfectly square when comparing bilateral muscle groups. Fine muscle tremors can be palpated and auscultated with a stethoscope. Concurrent signs of anxiety or pain should be noted, and the animal should be reevaluated in calm surroundings if necessary. In animals with spontaneous muscle activity, muscle groups should also be percussed with a percussion hammer. The triceps, pectoral, gluteal, and semitendinosus muscles are often easily accessed for percussion. A positive percussion sign occurs when the muscle holds a contracture for several seconds, creating a dimpled appearance below the contracted muscle (percussion myotonia) (Fig. 42-1). This occurs as the result of abnormal mechanical irritability and sustained contraction of the percussed fibers. Running a blunt instrument such as artery forceps, a needle cap, or a pen over the lumbar and gluteal muscles should illicit extension (swayback) followed by flexion (hogback) in healthy animals. Guarding against movement may reflect abnormalities in the pelvic or thoracolumbar muscles, or pain associated with the thoracolumbar spine or sacroiliac joints. A tail pull examination while the horse is standing still and walking can be used to assess rear limb weakness. If there is evidence of weakness, differentiation between muscular and neurologic origin is ideal. This requires a detailed neurologic examination and can often be extremely difficult. In general, muscular weakness is not associated with ataxia unless it is extremely severe. Weakness is often manifested by muscle fasciculations, knuckling at the walk, frequent recumbency with difficulty rising, and shifting of weight because of an inability to fix the stifles. If the primary abnormality identified is related to exertion, a lameness evaluation including flexion tests is often indicated as part of evaluation of the muscular system. Muscle pain may be secondary to changes in movement caused by skeletal pain. The horse should be observed at a walk or trot for any gait abnormalities and in some cases lunged for 15 minutes or ridden until clinical signs are elicited. Serum enzyme activities can be extremely useful in determining whether muscle cell necrosis is a predominant feature of a suspected muscle disease. Under normal conditions the serum activities of the enzymes used to assess muscle damage are low. However, leakage of the enzymes from myocytes into the bloodstream may occur if the cell membrane is disrupted through muscle cell necrosis or if the permeability of the cell membrane is increased. A number of other factors may influence the activities of enzymes within the circulation. These include rate of enzyme production, alternative sources of the enzyme, rates of enzyme excretion and degradation, and alterations to the pathways involved in enzyme removal or inactivation. Creatine kinase (CK), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activities in serum are used to assess muscle damage in large animals. Serum CK offers remarkable sensitivity as an indicator of myonecrosis and is predominantly located in skeletal and heart muscle. It is intimately involved in energy production within the cytoplasm and is readily liberated into the extracellular fluid when the muscle cell membrane is disrupted. Serum CK activity increases within hours of a muscle insult and peaks within 4 to 6 hours after injury (Fig. 42-2). Limited elevations in CK may accompany training, transport, and strenuous exercise. Elevations of CK to 400 or 500 IU/L may occur when training commences or in response to moderate exercise. Extreme fatiguing exercise (e.g., endurance rides or the cross-country phase of a 3-day event) may result in CK activities being increased to more than 1000 IU/L but usually less than 8000 IU/L. These elevations are not typically reflective of an extensive myopathy, and serum activities of CK rapidly return to baseline activities (i.e., <250 IU/L in 24 to 48 hours). Recumbent animals may also have slightly elevated CK activities that are usually less than 3000 IU/L. In contrast, more substantial elevations (from several thousand to hundreds of thousands of IU/L) in the activity of this enzyme may occur with rhabdomyolysis. Serum AST has high activity in skeletal and cardiac muscle and also in liver, red blood cells, and other tissues. Elevations in AST are not specific for myonecrosis, and increases can be the result of hemolysis, muscle, liver, or other organ damage. Alterations in AST activity are an integral component of many serum biochemical “profiles.” AST activity rises more slowly in response to myonecrosis than does CK, often peaking 24 hours after the insult (see Fig. 42-2), and the half-life of AST is much longer than that of CK. By comparing serial activities of CK and AST in animals with suspected myopathy, information concerning the progression of myonecrosis may be derived. Thus (1) elevations in CK and AST reflect relatively recent or active myonecrosis; (2) if CK remains persistently elevated, myonecrosis is likely ongoing; and (3) elevated AST activities accompanied by decreasing or normal CK activities indicate that myonecrosis is not continuing. Elevations in serum LDH activity are not specific to skeletal muscle and can occur with rhabdomyolysis, myocardial necrosis, and/or hepatic necrosis. Under ideal conditions samples for determination of serum CK, AST, and LDH should be harvested as soon as possible because anoxia and lysis of red blood cells allows the liberation of AST and LDH. They should be kept chilled (4° C, 39° F) if not taken immediately to a laboratory for analysis within 24 hours. When a delay of more than 12 hours is anticipated, freezing of the samples is desirable. Elevations in plasma/serum myoglobin concentrations provide an indication of recent muscle damage. Unfortunately, few laboratories can routinely measure myoglobin. Normal concentrations in resting horses have been determined by nephelometry (range 0 to 9 µg/L),1 with measured concentrations with rhabdomyolysis ranging from 10,000 to 800,000 µg/L.2 Urine can be obtained free catch from horses placed in stalls with fresh bedding or via catheterization. The most accurate reflection of fractional excretion of electrolytes is obtained from samples obtained without tranquilization. Urinalysis is particularly important in horses with myoglobinuria, elevations in creatinine, or suspected electrolyte imbalances. Urine specific gravity, protein content, white blood cell (WBC) count, red blood cell (RBC) count, and evaluation of cast formation should be performed to assess the potential for concurrent renal disease. A positive Hemastix test (ortho-toluidine) in the absence of hemolysis or RBCs in urine is highly suggestive of myoglobinuria. Further differentiation of myoglobin from hemoglobin is sometimes warranted and, where available, electrophoresis, nephelometry, or spectroscopy may be used. Spectroscopy does not always reliably distinguish between myoglobin and hemoglobin. Electrolyte, mineral, and creatinine concentrations in urine and blood have been used to determine electrolyte balance in horses with muscle cramping or exertional rhabdomyolysis.3 Problems often encountered, however, are the large fluctuations in daily electrolyte excretion that occur in the same horse and between horses, the interference of high urinary potassium concentrations with measures of sodium concentrations when an ion specific electrode is used, and the presence of calcium crystals in equine urine, which artifactually decrease the calcium and magnesium measured if urine samples are not acidified.4 Renal fractional excretions (FEs) can be calculated using the following formula: where U is urine, S is serum, x is measured electrolyte, and Cr is creatinine. If urine calcium is to be determined, acidification of urine to dissolve all calcium oxalate crystals is recommended to provide exact calcium excretion. Determination of potassium, chloride, magnesium, and phosphorus concentrations can be performed using ion-specific electrodes or by inductively coupled plasma atomic absorption. Normal values for FE of electrolytes depend on a horse’s diet. Normal values (%) for horses consuming grass, hay, and a sweet feed mix with available salt are FENa 0.04 to 0.08, FEK 35 to 80, FECl 0.4 to 1.2, FECa 5.3 to 14.5, FEP 0.05 to 4.1, and FEMg 14.2 to 21.4.4,5 Evaluation of muscle disorders that are precipitated by exercise may require an exercise challenge test. Horses should be observed for evidence of exercise intolerance, as well as muscle stiffness. An exercise test should not be used in horses with overt signs of rhabdomyolysis but rather to determine if horses not currently showing clinical signs are prone to exertional rhabdomyolysis. The goal is to induce subclinical elevations in serum CK activity. Abnormal increases in CK are more likely to occur if slow trotting is performed rather than strenuous exercise.6 Often 15 minutes of exercise at a walk and trot in unfit horses or at a constant slow trot in fit horses will elucidate subclinical elevations on CK. If signs of stiffness develop before this, exercise should be concluded. CK activities in blood samples taken immediately after exercise do not reflect the amount of exercise-induced muscle damage. For best results, blood samples for CK activity should be taken before and 4 to 6 hours after exercise. In healthy horses, 15 to 30 minutes of light exercise rarely causes more than a threefold increase in CK activity.7,8 Elevations greater than fivefold are indicative of exertional rhabdomyolysis. Standardized treadmill exercise testing can also be used to evaluate muscle responses and measure metabolic responses to exercise. Electrodiagnostic studies detect spontaneous or evoked potentials of neurogenic or myogenic origin using electrodes positioned in the muscle. Electromyography (EMG) is particularly useful to evaluate large animals with altered muscle tone. EMG of normal skeletal muscle shows a brief burst of electrical activity when the needle is inserted (insertional activity) in muscle and then quiescence, unless motor units are recruited (motor unit action potentials), or the needle is close to a motor end plate (miniature end plate potentials). Normal muscle shows little spontaneous electrical activity unless the muscles contract or the horse moves. Horses with abnormalities in the electrical conduction system of muscle, or denervation of motor units, show abnormal spontaneous electrical activity in the form of fibrillation potentials, positive sharp waves, myotonic discharges, or complex repetitive discharges.9–12 Fibrillation potentials and positive sharp waves represent spontaneous firing of muscle fibers. Myotonic discharges are bursts of complex high-frequency potentials, whereas complex repetitive discharges are similar but have fixed amplitude and frequency. They both represent abnormal simultaneous firing of groups of muscle fibers. Motor unit action potentials can be evaluated to assess their amplitude, duration, phase, and number of phases. Myopathic changes include a decrease in duration and amplitude of motor unit action potentials.10,12 More information about the motor unit could be provided by nerve conduction velocities (NCVs); however, the inaccessibility of motor nerves makes measurement difficult in large animals. Both EMG and NCVs are used to classify the primary disease as neuropathic or myopathic, to determine the distribution of the disease, and to provide insight into the pathophysiologic mechanisms of the disease.9,13 Equipment costs are relatively high, and expertise is required in operation and interpretation of results. Readers are advised to consult Chapter 35 before considering the use of EMG. Nuclear scintigraphy is useful for identification of some forms of muscle damage, particularly an area of deep muscle damage that was not suspected on the basis of clinical examination.14 Technetium 99 m methylene diphosphonate (MDP) is taken up in some damaged muscle in the horse and is best seen in the bone phase images (i.e., 3 hours after injection). Scintigraphy has been used in horses with a history of poor performance, with or without stiffness after exercise, to confirm a diagnosis of equine rhabdomyolysis.15 The mechanism of MDP binding is unknown, but the release of large amounts of calcium from damaged muscle or the exposure of calcium binding sites on protein macromolecules in the damaged muscle may be responsible. Scintigraphy may be helpful in some cases involving focal damage to either proximal forelimb or hindlimb muscles.14 Diagnostic ultrasonography is potentially useful for identification of muscle trauma, crepitus, fibrosis, and atrophy. Muscles have a rather typical striated echogenic pattern, but this varies according to the muscle group and careful comparisons must be made between similar sites in contralateral limbs, in both transverse and longitudinal images.14 The appearance of muscle is also sensitive to the way the animal is standing and whether the muscle is under tension, so it is important that the animal is standing squarely and bearing weight evenly. Muscle fascia appears as well-defined, relatively echodense bands.14 Care must be taken in identifying large vessels and artifacts created by them. In an acute injury, muscle fiber disruption is seen as relatively hypoechoic areas within muscle, with loss of the normal muscle fiber striation. The jagged edge of the margin of the torn muscle may be increased in echogenicity.14 Tears in the muscle fascia may be identified. The defect in muscle may be filled by loculated hematoma that is hypoechoic. As the muscle repairs it becomes progressively more echogenic. Relatively hyperechoic regions may be a result of increased connective tissue or loss of muscle cell mass. Hyperechoic shadowing artifacts usually represent mineralization or gas pockets.14 Examination of muscle fibers, neuromuscular junctions, nerve branches, connective tissue, and blood vessels within a biopsy sample can provide additional information necessary to fully characterize a neuromuscular disorder.16–18 Routine light and electron microscopic examinations, combined with histochemical evaluations, may provide insights into the particular manifestations of neuromuscular diseases and their rate of progression. A number of basic pathologic responses of muscle can be identified in paraffin-fixed sections. These include inflammatory infiltrates, muscle fiber necrosis, muscle fiber regeneration, increased number of central nuclei, variations in muscle fiber sizes and fiber shapes, vacuolar change, and proliferation of connective tissue. However, there are many pathologic alterations that cannot be detected in formalin-fixed tissue but can readily be seen in histochemical stains of fresh-frozen biopsy samples.16–18 These include muscle fiber types and their pattern of distribution, differentiation of neurogenic atrophy from disuse atrophy or a primary myopathy, characterization of vacuolar storage material, characterization of inclusion bodies, assessment of mitochondrial density, and additional clues that may allow identification of a specific disorder or category of muscle disorders. Furthermore, formalin fixation results in artifactual cracking, fiber shrinkage, and leakage of substrates such as glycogen, which can impact proper interpretation of muscle pathology. When considering collection of muscle biopsies, some general guidelines apply. Preferably, samples should be collected from what is considered abnormal or diseased muscle. A 6-mm-outer-diameter (Jørgen Kruuse A/S, Langeskov, Denmark) percutaneous needle biopsy technique can be used to obtain small muscle samples through a Responses of strips of fresh muscle to stimuli such as caffeine, halothane, and a variety of other agents can also be performed by specialized laboratories to diagnose recurrent exertional rhabdomyolysis and susceptibility to malignant hyperthermia but are not routine diagnostic procedures.19–21 Stephanie J. Valberg A muscle disorder is usually suspected in large animals because of (1) increased, decreased, or abnormal muscle tone; (2) focal or generalized muscle damage (rhabdomyolysis); (3) muscle atrophy; or (4) exercise intolerance not associated with respiratory, cardiovascular, or skeletal causes. Increased muscle tone may be neural in origin. For example, tetanus and strychnine poisoning increase muscle tone as a result of suppressed inhibition of upper motor neurons by interneurons. Increased motor neuron firing also occurs during seizures, with electrolyte imbalances and equine ear tick infestation. Visual, tactile, or auditory stimuli often precipitate painful sustained motor unit activity. Other probable neural disorders that intermittently increase muscle tone include periodic spasticity and spastic paresis in cattle, stiff horse syndrome, and “shivers” in draft and warmblood horses. Focal nerve root irritation may also result in focal muscle twitching. Increased muscle tone can also arise from myopathic disorders. Persistently enhanced muscle tone may occur because of muscle contractures, which are characterized by fixation of myofilaments in a persistently shortened position without neural input.22 Contractures are usually extremely painful and associated with rhabdomyolysis. Contractures occur with malignant hyperthermia and some forms of exertional myopathy. Intermittent, abnormal muscle contractions without rhabdomyolysis occur when sarcolemmal ion channels within the muscle cell membrane are dysfunctional.23,24 Caprine myotonia congenita and equine hyperkalemic periodic paralysis are examples of diseases caused by sarcolemmal ion channel dysfunction. Moderate weakness in horses may be caused by central spinal cord disorders. More profound weakness may arise from neuropathies affecting motor neurons (equine motor neuron disease, hypocalcemia); decreased neural input at motor end plates (botulism); marked muscle atrophy (equine motor neuron disease) or rhabdomyolysis of postural muscles; or severe electrolyte imbalances (hypokalemia). The few operative motor units fatigue easily, resulting in muscle fasciculations, shifting of weight, low head posture, difficulty prehending grain, and long periods of recumbency and difficulty rising. Atrophy is defined as a reduction in muscle size, specifically a reduction in muscle fiber diameter or cross-sectional area. Atrophy may occur in response to a variety of stimuli. Denervation removes the normal low-level tonic neural stimulus that is necessary to maintain muscle fiber mass. Complete denervation of a muscle results in more than a 50% loss of muscle mass within a 2- to 3-week period.16,25 A good example of this is “Sweeney” in horses, in which the suprascapular nerve is damaged and muscles over the scapula atrophy. Other denervating conditions such as equine motor neuron disease show a slower and more generalized progression of gross muscle atrophy. Electromyographic abnormalities following denervation are apparent within 5 days, and it may take 3 weeks for maximal changes to develop. Increased insertional activity, positive sharp waves, and bizarre high-frequency discharges and fibrillation potentials are seen in denervated muscle.12 Pyknotic nuclear clumps and small angular slow-twitch type I and fast-twitch type II fibers with concave sides are characteristic of neurogenic atrophy in muscle biopsies. In some cases, hypertrophy of remaining motor units may occur in neurogenic atrophy and renervation is indicated by target fibers and fiber type grouping. Muscle atrophy may also be caused by disuse, malnutrition, cachexia, corticosteroid excess, and immune-mediated myositis. Skeletal muscle is a plastic tissue, with approximately 1% to 5% of the contractile mass undergoing remodeling on a daily basis. If a negative nitrogen balance occurs, net protein withdrawal from the skeletal muscle mass begins within 48 to 72 hours. This type of atrophy is distinguished from neurogenic atrophy by a slower progression of atrophy, normal electromyographic findings, and muscle biopsies that are characterized by primarily atrophy of type II muscle fibers. The overall response of skeletal muscle is to maintain essential postural muscle groups, whereas less essential groups undergo significant reduction in muscle mass. With malnutrition, 30% to 50% of the muscle mass may be lost in the first 1 to 2 months.25 Rapid atrophy is characteristic of immune-mediated myopathies in Quarter Horse−related breeds, which can result in the loss of 30% of muscle mass within 48 hours due to necrosis and atrophy of myofibers.26 Muscle necrosis (rhabdomyolysis) as evidenced by elevations in serum CK, LDH, and AST can be focal or generalized. Many infectious, toxic, nutritional, ischemic, and idiopathic factors result in muscle fiber necrosis. When attempting to identify an etiology, it is helpful to characterize rhabdomyolysis in horses as associated with exercise or not. Specific causes of exertional and nonexertional rhabdomyolysis are listed in Boxes 42-1 to 42-3. Necrosis represents injury to organelles within a muscle fiber or within a segment of that fiber. Many myopathies associated with generalized rhabdomyolysis interrupt normal muscle metabolism, and cell death results from an inability to maintain homeostasis within the myofiber. Although a variety of external or internal insults may cause rhabdomyolysis, they often share a final common pathway leading to cell death.27 Under normal conditions, considerable energy is expended by muscle cells to pump the calcium that accumulates in the sarcoplasm during contraction into the sarcoplasmic reticulum. If cell membrane function is disrupted or if the energy pathways that generate adenosine triphosphate for the calcium pump are impaired, excessive calcium may accumulate in the sarcoplasm. Although some calcium can be sequestered by the mitochondria, eventually mitochondria become overloaded and oxidative metabolism ceases; oxygen free radicals are generated; phospholipases are activated, inducing the arachidonic cascade; calcium-dependent proteases are stimulated; and complement is activated. Lipid storage disorders and antioxidant deficiencies may also cause necrosis through destruction of mitochondrial and sarcolemmal membranes. The contractile proteins within a necrotic segment are destroyed and appear homogenized with no evidence of cross-striations, and mitochondrial and sarcolemmal membranes appear disrupted. When necrosis occurs as a result of internal disruption of muscle homeostasis, the basement membrane of the cell is left intact. Macrophage infiltration and phagocytosis of necrotic debris usually occur within 16 to 48 hours of the muscle injury. Satellite cells migrate along the remaining basement membrane and form regenerative myotubes within 3 to 4 days of injury, with mature muscle fibers developing within a month of the original damage.16 Muscle ischemia occurs commonly with acute trauma, the compartment syndrome in recumbent animals, downer syndrome, and vascular occlusion. Compartment syndrome often involves the triceps muscle or extensors of the hindlimb because they are often compressed in down animals or during anesthesia. Hypotension during surgery contributes to the development of this syndrome. Acute muscle infarction may occur with purpura hemorrhagica or disseminated intravascular coagulation, and on postmortem examination characteristic well-demarcated areas of hemorrhagic necrosis are evident. Muscle areas in contact with the ground in recumbent animals are most susceptible to infarctions in animals with vasculitis. Clinically, acute infarctions are an extremely painful condition that may resemble colic. Chronic occlusive diseases, such as iliac thrombosis, often allow collateral circulation to develop, thereby avoiding acute signs of ischemia at rest. Although muscle has an impressive ability to regenerate, if a disease process is severe enough to disrupt the basement membrane, muscle may be replaced by connective tissue and fat. This occurs most frequently after trauma, such as following tearing of the semimembranosus/tendinosus in horses (fibrotic myopathy) and with severe infarctions. Stephanie J. Valberg Myotonic muscle disorders represent a heterogeneous group of diseases that share the feature of delayed relaxation of muscle after mechanical stimulation or voluntary contraction. Abnormal muscle membrane excitability appears to be the shared abnormality among myotonic disorders. The nondystrophic myotonias in large animals include myotonia congenita in horses and goats and equine hyperkalemic periodic paralysis.28 Sarcolemmal ion channel dysfunction causes these nondystrophic myotonias. Dystrophic myotonia, a progressive disease that may also be associated with abnormalities in other body systems, has been reported in horses.29,30 In addition, it has been noted that some horses with ear tick infestations develop percussion myotonia and painful muscle cramps.31 A condition that demonstrates myotonic-like signs in cattle is spastic paresis,32,33 or Elso heel. Commonly, calves between 2 and 7 months of age are affected and have an extremely straight angle to the hock and stifle. Signs reflect a decreased capacity or inability to flex the hock because of continuous tension on the gastrocnemius muscle when standing. Involvement may be unilateral or bilateral. The Holstein-Friesian breed is most commonly affected, although other breeds have been found to suffer the disorder.32–35 Spastic paresis may have a distinct familial pattern, but environmental exposure to toxins in utero have also been implicated as a cause.32–34,36 Clinical signs similar to spastic paresis are seen in horses with shivers, which is most commonly seen in draft horse breeds, warmbloods and warmblood crosses older than 1 year of age, and Thoroughbreds, although it may occur in light horse breeds.37 Horses are generally taller than 16.3 hands and more often male than female. Suggested causes include genetic, traumatic, infectious, and neurologic diseases, although its exact basis is unknown. The disease primarily affects the hindlimbs and is characterized by periodic, involuntary spasms of the muscles in the pelvic region, pelvic limbs, and tail, which are exacerbated by backing or picking up the hindlimbs. The affected limb is elevated and then abducted. It may actually shake and shiver, and the tailhead usually elevates concurrently and trembles. In more severely affected animals, on backing up the hindlimb is suddenly raised, semiflexed, and abducted with the hoof held in the air for several seconds or minutes. The tail is elevated simultaneously and trembles. After a variable period of time, the spasms subside, the limb is extended, and the foot is brought slowly to the ground. There are no distinct myotonic discharges on electromyography with shivers, indicating it is not a true myotonic condition. Myotonia congenita in humans, horses, and goats is usually detected in the first year of life.38–41 Affected animals commonly have conspicuously well-developed musculature and display mild to moderate pelvic limb stiffness. Gait abnormalities are usually most pronounced when exercise begins and frequently diminish as exercise continues. Bilateral bulging (dimpling) of the thigh and rump muscles is often obvious and gives the impression that the animal is well developed (Fig. 42-3). Stimulation of affected muscles, especially percussion, exacerbates the muscle dimpling below a large area of tight contraction (Fig. 42-4). Affected muscles may remain contracted for up to a minute or more with subsequent slow relaxation.30,41 Myotonia congenita does not usually show progression of clinical signs beyond 6 to 12 months of age in horses.30 In goats, myotonia congenita appears to be an autosomal dominant mutation in the skeletal muscle chloride channel (CLCN1) that has incomplete penetrance.24,40,42 Affected goats are commonly referred to as “fainting goats.” Signs are usually recognizable by 6 weeks of age and vary from stiffness after rest to marked general rigidity after visual, tactile, or auditory stimulation. Clinical signs remain throughout the animal’s life but are not progressive.43 An autosomal recessive c.1775A>C mutation was identified in a New Forrest Pony with congenital myotonia. The missense mutation results in a substitution of aspartic acid for alanine in codon 592 of the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain of the equine CLCN1 protein.44 Myotonia dystrophica appears to be a separate form of myotonia in horses.29,30,45 Severe clinical signs of myotonia that progress to marked muscle atrophy and possibly involve a variety of organ systems have been observed in Quarter Horse, Appaloosa, and Italian-bred foals. Retinal dysplasia, lenticular opacities, and gonadal hypoplasia have been reported in one such Quarter Horse foal.29 This condition resembles myotonia dystrophica in humans, which is caused by genetic mutations involving either the DMPK gene or the ZNF9 gene.46,47 In both cases, a short segment of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is abnormally repeated many times, forming an unstable region in the gene, which alters messenger ribonucleic acid (RNA) processing. The genetic basis of myotonic dystrophy in horses is not yet known. A tentative diagnosis frequently can be made on the basis of age; clinical signs (stiff gait, particularly at the onset of exercise); muscle bulging; and prolonged contractions following muscle stimulation. Definitive diagnosis of myotonia is usually based on electromyographic examination. Affected muscle manifests pathognomonic, crescendo-decrescendo, high-frequency repetitive bursts with a characteristic “dive bomber” sound.29,45,48 This sound is produced by the repetitive firing (after contractions) of affected muscle fibers. After a contraction diminishes, the excitability of muscle fibers is decreased and the action potentials recorded by the EMG reflect the diminution of electrical activity.49 Examination of muscle biopsies from foals with myotonia congenita may be normal or may demonstrate extremely variable muscle fiber dimensions up to twice those of normal age-matched controls.41 Type I fiber hypertrophy or hypotrophy may be seen. The major changes noted with myotonic dystrophy are ringed fibers, alterations in the shape and position of myonuclei, sarcoplasmic masses, and an increase in endomysial and perimysial connective tissue.29,30,45,50 Fiber type grouping and atrophy of both type I and type II muscle fibers may be present. Considering that the pathophysiologic basis of myotonia in horses has not been clearly identified, recommendations for specific, effective therapy are almost impossible. In affected humans and dogs some relief of signs has been provided by drugs such as quinine, procainamide, and phenytoin. However, responses vary among patients. Phenytoin has been reported to be efficacious in two Quarter Horses with hyperkalemic periodic paralysis and myotonic dystrophy.48 Prognosis appears to be variable and dependent on the severity of clinical signs. Mildly affected animals with congenital myotonia may undergo some amelioration of clinical signs with increasing age over a period of months to years. The reason(s) for this regression of signs is unknown. Other, more severely affected horses, particularly those with dystrophic myotonia, may have progression of signs, including atrophy and fibrosis or pseudohypertrophy to the point at which the animal is no longer able to move without great pain and difficulty (Fig. 42-5). Euthanasia of such animals is often warranted. Although conclusive evidence regarding the genetic basis of dystrophic myotonia in horses is still not available, owners of affected horses should be cautioned as to the possibility of this disease being heritable. Sharon Jane Spier Equine hyperkalemic periodic paralysis (HYPP) is caused by an inherited defect in the skeletal muscle sodium channel.28,51–54 This myopathy manifests as abnormal skeletal muscle membrane excitability leading to episodes of myotonia, or sustained muscle contraction, and paralysis. In humans, numerous muscle membrane channel defects (so-called channelopathies) have been characterized, and the molecular basis for disease is well described.39 Other reported disorders with suspected membrane defects in horses include myotonic dystrophy and congenital myotonia.29,41 Hyperkalemic periodic paralysis was the first equine disease attributed to a specific genetic mutation and detectable through DNA technology.53 Hyperkalemic periodic paralysis is an autosomal dominant trait affecting Quarter Horses, American Paint Horses, Appaloosas, and Quarter Horse crossbred animals worldwide. A “syndrome” in related horses was first recognized in the 1980s by breeders and veterinarians and first reported to be similar to HYPP in humans by Cox at the American Association of Equine Practitioners convention in 1985.54 In December 2002, this genetic disease was publicly linked to a popular Quarter Horse sire named Impressive. This prolific sire, born in 1969, has more than 500,000 offspring registered with the AQHA (AQHA registrar, personal communication, 2012), and these offspring dominate the halter horse industry. Current estimates indicate that 1.5% of Quarter Horses and 4.5% of Paints are affected.55 Notably, however, 58% of halter horses have the HYPP mutation.55 Unfortunately, the gene frequency has not decreased in the past 20 years since genetic testing has been available to breeders, and controversy continues among horse breeders whose stock carry this gene (statistics from UCD Veterinary Genetics Laboratory HYPP Testing, 2006). Affected horses appear to have been preferentially selected as breeding stock due to their pronounced muscle development, and there is evidence of selection of HYPP-affected horses as superior halter horses by show judges.56 In 1996, AQHA officially recognized HYPP as a genetic defect or undesirable trait. To increase public awareness of this genetic defect, mandatory testing for HYPP with results designated on the Registration Certificate began for foals descending from Impressive born after January 1, 1998. In response to requests from the membership, the AQHA Stud Book and Registration Committee ruled that foals born in 2007 and later testing homozygous affected for HYPP (H/H) are not eligible for registration. Breeders opposed to restrictions argue that the disease can be controlled through diet and medication and that these horses are highly successful in the show ring.57

Diseases of Muscle

Examination of the Muscular System

Physical Examination

Clinical Pathology

Serum Enzyme Activities and Myoglobin Concentrations

Urinalysis

Exercise Testing

Electromyography

Nuclear Scintigraphy

Ultrasonography

Muscle Biopsy

-inch skin incision using a local anesthetic subcutaneously. If this technique is used, enough muscle should be obtained to form a

-inch skin incision using a local anesthetic subcutaneously. If this technique is used, enough muscle should be obtained to form a  -inch square sample at a minimum. These samples do not, however, tolerate shipment to an outside laboratory. The optimum biopsy for shipment of histopathology tissues to a laboratory is collected using surgical or open techniques, performed under local anesthesia. Care must be exercised to infiltrate only the subcutaneous tissues, not the muscle, with the anesthetic agent. The objective is to obtain approximately a

-inch square sample at a minimum. These samples do not, however, tolerate shipment to an outside laboratory. The optimum biopsy for shipment of histopathology tissues to a laboratory is collected using surgical or open techniques, performed under local anesthesia. Care must be exercised to infiltrate only the subcutaneous tissues, not the muscle, with the anesthetic agent. The objective is to obtain approximately a  -inch cube of tissue; hence a suitably long skin incision is required. Two parallel incisions

-inch cube of tissue; hence a suitably long skin incision is required. Two parallel incisions  inch apart should be made longitudinal to the muscle fibers with a scalpel. The muscle should only be handled in one corner using forceps, and crushing should be avoided. The muscle sample is then excised by cross-secting incisions

inch apart should be made longitudinal to the muscle fibers with a scalpel. The muscle should only be handled in one corner using forceps, and crushing should be avoided. The muscle sample is then excised by cross-secting incisions  inch apart, and the tissue is fixed appropriately. Routine histopathology samples can be placed in formalin; fresh samples can be placed in a watertight hard container after being wrapped in gauze lightly moistened with saline and shipped chilled to laboratories for freezing. On arrival at specialized laboratories, fresh samples for histochemical analysis are fixed in isopentane (methylbutane) chilled in liquid nitrogen to ensure rapid freezing and minimization of freeze artifact. Samples that potentially may be used for biochemical analysis should be immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Other routine histopathologic techniques may also be of diagnostic value. A special fixative may be required if such practices are to be undertaken. Samples for electron microscopy (EM) require appropriate fixation in glutaraldehyde preparations. Ideally, thin sections of muscle for EM should be clamped in vivo to maintain fibers at a resting length before they are excised. However, if pathology other than the alignment of thick and thin myofilaments is to be investigated, small muscle pieces can be excised and placed directly in appropriate EM fixative.

inch apart, and the tissue is fixed appropriately. Routine histopathology samples can be placed in formalin; fresh samples can be placed in a watertight hard container after being wrapped in gauze lightly moistened with saline and shipped chilled to laboratories for freezing. On arrival at specialized laboratories, fresh samples for histochemical analysis are fixed in isopentane (methylbutane) chilled in liquid nitrogen to ensure rapid freezing and minimization of freeze artifact. Samples that potentially may be used for biochemical analysis should be immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Other routine histopathologic techniques may also be of diagnostic value. A special fixative may be required if such practices are to be undertaken. Samples for electron microscopy (EM) require appropriate fixation in glutaraldehyde preparations. Ideally, thin sections of muscle for EM should be clamped in vivo to maintain fibers at a resting length before they are excised. However, if pathology other than the alignment of thick and thin myofilaments is to be investigated, small muscle pieces can be excised and placed directly in appropriate EM fixative.

Classification of Muscle Disorders

Altered Muscle Tone

Muscle Atrophy

Muscle Necrosis

Disorders of Muscle Tone

Myotonic Disorders

Myotonia

Clinical Signs

Diagnosis

Treatment

Prognosis

Hyperkalemic Periodic Paralysis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Diseases of Muscle

Chapter 42