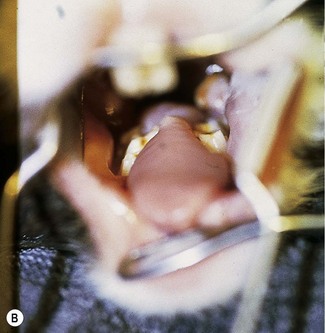

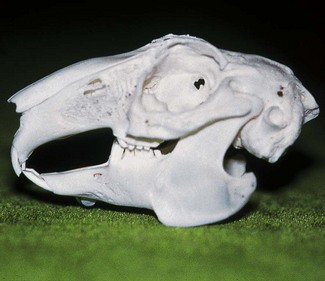

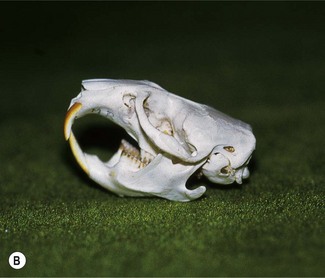

Chapter 14 The Order of Lagomorphs includes rabbits, hares, cottontails and pikas. All teeth in lagomorphs are aradicular hypsodont. They have four incisor teeth in the upper jaw. This clearly differentiates them from rodents who only have two incisors in the upper jaw. The lagomorphs do not have canine teeth (Box 14.1). The four incisor teeth in the upper jaw are placed in two rows with the two large incisors located labially and the two smaller rudimentary incisors (peg teeth) located palatally. In occlusion, the crown tips of the mandibular incisor teeth rest between the 1st and 2nd row of upper jaw incisors. At rest, the incisors are held in occlusion and the cheek teeth are held out of occlusion (Crossley 1995a). A relatively normal rabbit skull is depicted in Figure 14.1. Fig. 14.1 Normal rabbit skull Rabbits do not gnaw like rodents, unless there is some cheek tooth problem interfering with normal mastication (Crossley 1995a). The incisors are mainly used in a lateral slicing motion, so they more or less cut their food into smaller apprehensible pieces. The large upper incisors grow at an average rate of 2.0 mm per week and the lower incisors at a rate of 2.4 mm per week (Wiggs and Lobprise 1995). A rabbit with normal incisor occlusion, eating a normally abrasive diet such as hay, grass and fresh greens, will wear down the teeth at a similar rate. The incisor teeth have thick white enamel on the labial surface and almost no enamel on the palatal/lingual surface. Normal tooth wear thus results in a chisel-shaped tooth as the softer dentine wears down faster than the thick enamel. A large diastema separates the incisor teeth from the cheek teeth (premolar and molar teeth). The dental formula (Box 14.2) varies among the species, ranging from 16–22 teeth. However, all rodents have four incisors (one in each quadrant) and no canine teeth. A diastema separates the incisors from the cheek teeth. At rest (Fig. 14.2A), the mandible is in a caudal position and the incisors are out of occlusion (Crossley 1995b). During gnawing, the incisors are held in occlusion (Fig. 14.2B). Fig. 14.2 Normal rat skull Guinea pigs need vitamin C supplementation (Flecknell 1991; Schaeffer and Donnelly 1997). A daily dose of 10 mg/kg is recommended for normal activity; this should be increased (up to 30 mg/kg) in situations of stress (e.g. change of environment, pregnancy, illness, new pet). There are commercially available vitamin C drops, powders and tablets that can be added to the food or the water. However, Vitamin C is unstable (easily oxidized by light and air) and therefore adding to food is preferable to putting in drinking water. Tooth overgrowth commonly results in malocclusion. Complications to malocclusion include: • Traumatization of oral soft tissues (cheeks, tongue) by the overgrown teeth • Apical overgrowth with resultant penetration of upper teeth into the ocular sockets and/or sinuses • Apical overgrowth of the mandibular teeth with resultant penetration of the ventral border of the alveolar bone in the mandible • Retrobulbar and/or facial abscessation • Inability to close the mouth • Inability to chew (lateral slicing motion in lagomorphs; gnawing in rodents). • Salivation, wet chin, dirty forelimbs • Changes in grooming behavior • Accumulation of cecotrops around anus (predisposing to ‘fly strike’). Inspection and palpation of the face and oral cavity is the next step (Box 14.3). As in other species, thorough intraoral examination requires general anesthesia. Sedation and anesthesia in pocket pets is covered in other texts and will not be dealt with here. Aids such as mouth gags and cheek dilators are necessary to open the mouth. We do not use mouth gags in rabbits. Instead, we use cheek dilators as shown in Figure 14.3. We do use a light model mouth gag for most other species. Risks associated with using a mouth gag are damage to the teeth and damage to the temporomandibular joint (if the mouth is opened excessively). Fig. 14.3 Access to the oral cavity Additional tools include spatulas to depress the tongue or push it aside. Good lighting is mandatory, and often not easy to achieve – a pen torch or headlight is useful. Endoscopy using a rigid endoscope is useful to identify subtle lesions (Capello et al. 2005a). Crown elongation, spikes, lacerations of tongue and oral mucosa, and missing teeth should be noted and recorded. The sulcus of each tooth should be examined with a periodontal probe to identify pathologic periodontal pockets. Even under general anesthesia, it is estimated that only 50% of pathology will be detected (Crossley 2000). In other words, disease is underestimated and oral examination under anesthesia needs to be complemented by imaging (radiography or CT scan, ultrasonography and MRI for abscesses). Three basic skull views need to be taken, namely lateral, dorsoventral and rostrocaudal. Of these, the lateral view is usually the most informative. Additional oblique lateral views are necessary for most patients. When possible, additional intraoral views to avoid superimposition of adjacent structures are recommended. The techniques for intraoral radiography are outlined in Chapter 7. Detail is essential, so non-screen films are required. Suggested exposure time for the rabbit, guinea pig and chinchilla is as follows: Even with radiographic examination, a lot of the pathology will be missed. Radiographic interpretation by an experienced examiner will only reveal around 85% of the pathology present (Crossley 2000). CT-scan will give more information, especially for the detection of early cheek tooth pathology (Crossley et al. 1998; Van Caelenberg et al. 2010). Other examinations that may be indicated are ultrasonography (for retrobulbar abscesses) or MRI (for soft tissue lesions). Fig. 14.4 Lateral radiograph of a normal rabbit • The palatine shelf and the dorsal border of the mandible converge rostrally • Ideally, with the incisors in occlusion, the cheek teeth should be out of occlusion. This is rarely seen in pet rabbits. As soon as both are in occlusion, there is some degree of cheek tooth overgrowth. However, as long as the maxilla and mandible converge rostrally, this is not a clinical problem • Smooth ventral mandibular border • Normal radiolucencies of the periapical germinal tissues • The apices of the maxillary incisor teeth should not penetrate the palatine shelf • The apices of the maxillary incisor teethe are located halfway along the diastema • The apices of the mandibular incisors are located level to, or just rostral of, the first mandibular cheek teeth. Primary incisor overgrowth is seen in young animals. It occurs regularly in dwarf rabbits. Due to the jaw length discrepancy (i.e. the mandible is too long with respect to the maxilla), normal incisor occlusion is not established. The mandibular incisors occlude either level with or rostral to the large labial row of maxillary incisors. The result is that normal incisor wear does not occur. The upper incisors may curl inward (Fig. 14.5A) or flare out laterally (Fig. 14.5B), and the mandibular incisors protrude from the mouth. If eruption of the maxillary incisors is hindered, e.g. mechanical obstruction by abnormal occlusal forces, then tooth growth will occur in an apical direction and may result in perforation of the palatine shelf. When significant incisor malocclusion has developed, the animal cannot close its mouth normally and secondary cheek tooth overgrowth will develop over time. Radiographic features of primary incisor overgrowth are shown in Figure 14.6. If the condition is identified early, i.e. before excessive secondary cheek tooth overgrowth has occurred, the prognosis is relatively good with appropriate treatment. Fig. 14.5 Rabbit – incisor overgrowth (clinical presentation) Fig. 14.6 Rabbit – primary incisor overgrowth (lateral radiograph) Cheek tooth abnormalities are very common in pet rabbits. As already mentioned, most rabbits presented for treatment of incisor tooth overgrowth have the incisor overgrowth secondarily to the cheek tooth overgrowth, i.e. the cheek tooth overgrowth is the primary cause. Although calcium and vitamin D deficiency may be involved in the etiology (Harcourt-Brown and Baker 2001), the primary cause of cheek tooth overgrowth is thought to be feeding diets that provide insufficient abrasion (Crossley 1995a; Redrobe 1997). Late-stage disease is easy to diagnose. On conscious intraoral examination with an otoscope, the massive overgrowth of the cheek teeth is usually clearly visible. The upper cheek teeth flare out buccally (Fig. 14.7A), causing buccal ulceration and wounds. The lower cheek teeth show spikes on the lingual side (Fig. 14.7B), often associated with wounds on the tongue. The rabbit at this stage is unable to use the normal lateral chewing movements. It may be anorectic but if it is still eating, then it will only be able to consume soft fresh food or dry food, which does not need much chewing.

Dental diseases in lagomorphs and rodents

Dental anatomy

At rest, the incisors are held in occlusion and the cheek teeth are out of occlusion.

Rodents

(A) At rest, the mandible is held in a caudal position. The incisors are then out of occlusion and the cheek teeth are in occlusion. (B) For gnawing, the mandible is moved rostrally so that the incisor teeth are brought into occlusion.

Husbandry

Consequences of tooth overgrowth

Examination

Examination of the face and oral cavity

Cheek dilators can be used to open a rabbit’s mouth. We rarely use mouth gags in rabbits. This method gives both good visibility and access. It can be used even when the incisor teeth have been extracted.

Radiographic examination

Further examination

Rabbits

Normal radiographic features

Note that the palatine shelf and the dorsal border of the mandible converge rostrally.

Incisor overgrowth

(A) The upper incisors curl into the oral cavity. (B) The upper incisors flare out laterally.

There is slight overgrowth of the cheek teeth, which causes the palatine shelf and dorsal border of the mandible to be parallel rather than converge rostrally.

Cheek tooth overgrowth

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Dental diseases in lagomorphs and rodents