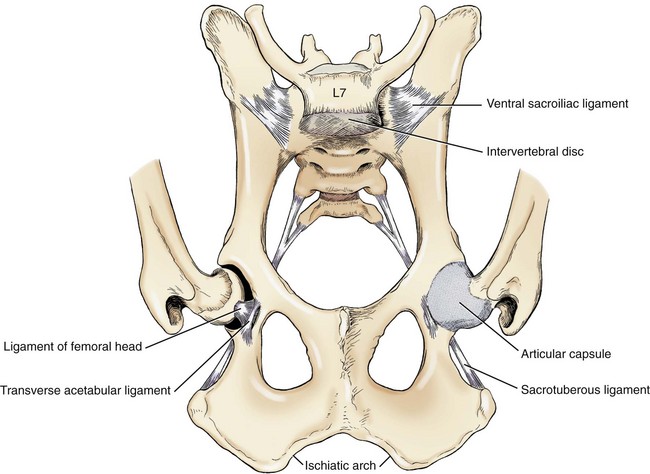

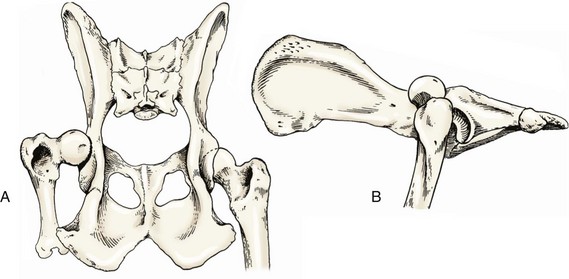

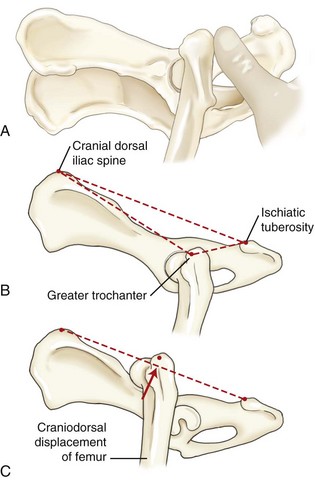

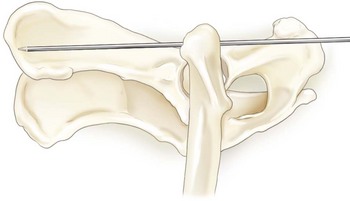

Chapter 58 The coxofemoral joint is a diarthrodial articulation between the femoral head and acetabulum. The ball-and-socket configuration provides stability while allowing a wide range of joint motion. Primary stabilizers of the hip joint include the ligament of the head of the femur, which extends from the fovea capitis in the femoral head to the acetabular fossa; the joint capsule, which attaches medially near the acetabular rim and laterally on the femoral neck; and the dorsal acetabular rim21 (Figure 58-1). Luxation occurs with functional loss of two or more of these primary joint stabilizers.31,58 The acetabular labrum provides secondary stabilization of the hip joint and comprises a thin, fibrocartilaginous band that extends laterally from the dorsal acetabular rim. Ventrally, this fibrocartilaginous band extends across the acetabular notch as the transverse acetabular ligament. Secondary stabilization is also provided by the hydrostatic pressure created by the presence of joint fluid within the joint and by the periarticular muscles, which traverse the joint.24 These muscles include the deep, middle, and superficial gluteal muscles, which lie dorsal and cranial to the hip joint and extend, internally rotate, and abduct the hip joint. Other periarticular muscles include the iliopsoas, quadratus femoris, gemelli, internal obturator, and external obturator muscles.21 Coxofemoral luxation is common in dogs and cats, accounting for up to 90% of all joint luxations.* Vehicular trauma is the cause of up to 85% of coxofemoral luxations reported in the literature.4,10 Other reported causes include severe hip dysplasia, falls, spontaneous luxation, and unknown trauma.30,37,61 Bilateral luxations account for up to 6% of canine and 9% of feline luxations.4,19 Injuries to other body systems occur concurrently in up to 55% of patients with coxofemoral luxation.4,10,43 In immature animals, fracture of the capital physis (Salter-Harris type I) occurs more often than hip luxation.13 Luxations are described by the direction the femoral head moves relative to the acetabulum; most coxofemoral luxations (75%) are craniodorsal49 (Figure 58-2). This typically occurs when trauma to the rear limb exerts supraphysiologic forces on the femur. As a result of trauma, the animal falls laterally, placing the distal femur in adduction and distracting the femoral head from the acetabulum until the ligament of the head of the femur and the joint capsule are stretched. When the greater trochanter strikes the ground, the femoral head is forced over the dorsal rim of the acetabulum, causing a tear of the joint capsule (midsubstance tear or avulsion of the dorsal joint capsule from the acetabulum or femoral neck) and tearing of the ligament of the femoral head. Alternatively, luxation may occur if the limb is in adduction and a dorsally directed force is applied to the limb (or a ventrally directed force is applied to the pelvis). Concurrent external rotation of the hip may facilitate luxation. Once luxation occurs, the pull of the gluteal muscles aids in displacing the femoral head craniodorsally to a position adjacent to the ilial body or dorsal to the acetabular rim.62 The luxation results in tearing and contusion of the periarticular muscles and the articular cartilage. Injury to the cartilage also results from subsequent contact and abrasion of the femoral head with the pelvis outside of the acetabulum, along with loss of lubrication and nourishment normally provided by the synovial fluid.62 Ventral and caudal luxations occur less frequently and may be associated with concurrent avulsion fracture of the greater trochanter.29,54 Such luxations typically occur when a traumatic incident forces the rear limb into abduction. If the limb rotates internally as the hip is luxating ventrally, the femoral head will be displaced into the obturator foramen. Simultaneous external rotation will position the luxated femoral head adjacent to the pubis. Ventral luxations may also occur iatrogenically when attempts are made to reduce a craniodorsal luxation. Coxofemoral luxation may be identified palpably by placing a thumb in the ischiatic notch (between the greater trochanter and the ischiatic tuberosity) and externally rotating the femur (Figure 58-3, A). If the femoral head is normally seated within the acetabulum, the thumb will be displaced from the ischiatic notch with external rotation of the femur. However, if the femoral head is luxated, the clinician’s thumb is not displaced when the femur is rotated. The integrity of the coxofemoral joint may also be evaluated by palpation of the craniodorsal border of the ilium, the greater trochanter, and the ischiatic tuberosity. When the hip is reduced, the greater trochanter is positioned distal to the axis of a line drawn between the cranial dorsal iliac spine and the ischiatic tuberosity, and it is positioned markedly closer to the ischiatic tuberosity than the cranial dorsal iliac spine. With a craniodorsal luxation, the greater trochanter is equidistant from both points (Figure 58-3, B). With ventral and caudoventral luxations, the greater trochanter is displaced medially, and hip adduction and internal rotation may be constrained by entrapment of the femoral head within the obturator foramen. Radiographic evaluation of the hip is required to confirm the luxation, determine the direction of the luxation, and evaluate for other abnormalities. Lateral and ventrodorsal projections should be obtained. Radiographs should be evaluated for the presence of acetabular or other pelvic fractures, femoral head or neck fractures, slipped capital physis (in immature patients), and evidence of hip dysplasia (Figure 58-4). Reduction and stabilization of the coxofemoral joint is preferred in most cases and may be accomplished using closed or open techniques. Conservative treatment can be tolerated in some cats in which, without reduction, a pseudoarthrosis may develop between the luxated femoral head and the caudal portion of the ilium, allowing limited, pain-free function.1,54 However, reduction and stabilization of the joint is recommended in cats that fail to bear weight on the limb within 4 to 5 days of injury, and in all dogs with coxofemoral luxation. Joint reduction should be performed soon after injury to minimize destruction of cartilage, and before muscle spasticity and fibrosis prevent easy relocation. Diagnosis and management of concurrent injuries may take precedence; treatment for shock, supportive care, and thorough evaluation of the patient (including thoracic radiographs) should be provided in patients that have sustained recent trauma. Although not a surgical emergency, hip luxation should be treated within 72 hours to minimize pathologic changes to the femoral head and acetabulum. Reduction is significantly more difficult 4 to 5 days after luxation.22,43 In most cases, closed reduction of the coxofemoral luxation is attempted first. Although closed reduction is unsuccessful in many cases, attempted closed reduction before open surgical reduction does not appear to alter the long-term prognosis.10 However, initial open (surgical) reduction is indicated if acetabular or femoral head fractures are present, the joint reluxates after radiographically confirmed closed reduction, concurrent injuries require immediate return of hip function, or the luxation is chronic and visual evaluation of the cartilage is necessary.9 In dysplastic joints, restoration of joint stability may not be possible because of preexisting pathology, and alternatives such as femoral head and neck ostectomy or total joint replacement should be considered.9,10,49 Closed reduction is usually successful if performed in the first few days after luxation. Closed reduction may be unsuccessful because of intra-articular fracture, muscle contracture, the presence of soft tissue or hematoma within the acetabulum, inflammation of the ligament of the head of the femur, or periarticular fibrosis.* The patient is placed under general anesthesia to relax the muscles and eliminate pain during hip manipulation, and is positioned in lateral recumbency with the luxated limb uppermost. Sedation along with epidural or spinal anesthesia is an alternative to general anesthesia in higher-risk patients.14 An assistant places a small towel or rope in the patient’s inguinal area to provide countertraction and to stabilize the pelvis during reduction. Initially, in cases of craniodorsal luxation, the femoral head is disengaged from the dorsal acetabular rim by grasping the hock and stifle and externally rotating the limb. Traction is then applied to the limb in a distocaudal direction to align the femoral head over the acetabulum. The limb is internally rotated and abducted to seat the femoral head into the acetabulum. Digital pressure applied to the greater trochanter may be helpful in directing the femoral head into the acetabulum. For cranioventral luxation, the femoral head may be manipulated into the craniodorsal position and then reduced as just described. Alternatively, the limb is grasped with one hand, while the other places countertraction on the pelvis. The femoral head is displaced laterally and then caudally into the acetabulum. For caudoventral luxation, the femoral head is disengaged from the obturator foramen using traction on the limb and countertraction on the ischiatic tuberosity. Abduction of the limb may be helpful. In cats and small to medium-sized dogs, a ventrally directed force, carefully applied directly to the head of the femur by a gloved finger placed in the rectum, may aid in disengaging the femoral head from the obturator foramen. Once the femoral head is disengaged from the obturator foramen, the femoral head is manipulated laterally and cranially into the acetabulum. Once the joint is reduced, a medially directed force is applied to the trochanter as the limb is manipulated through a full range of motion to displace blood clots, joint capsule, and other soft tissues from the acetabulum. Joint stability is assessed during gentle manipulation of the hip, including flexion, extension, external rotation, and distraction of the femoral head. Reluxation occurs most often during external rotation and extension and is more likely in dysplastic joints or with chronic luxation. Reluxation has been reported in more than 50% of cases following closed reduction alone.4,10,19,43 Therefore, the application of closed or open techniques to stabilize the joint is recommended after closed reduction.4,24,43 Ehmer Sling.: After closed reduction of a craniodorsal hip luxation, a non–weight bearing sling (Ehmer sling or figure-of-eight bandage) is typically applied to the hindlimb to maintain reduction. The Ehmer sling flexes the hip joint and abducts and internally rotates the femur to position the femoral head within the acetabulum20,24,43 (see Chapter 45). Nonelastic adhesive tape is the preferred material for this bandage. A mediolateral radiographic view of the hip joint is obtained and is usually sufficient for assessment of joint reduction. A ventrodorsal radiograph may be obtained if necessary, although caution is necessary to avoid displacing the femoral head or disrupting the sling. The sling is generally required for 10 to 14 days, until the joint capsule and the periarticular soft tissues are sufficiently healed to maintain reduction. The patient must be monitored closely for complications such as slipping of the sling, foot swelling due to vascular compromise, and decubital ulcer formation, and to prevent necrosis of the distal extremity.19,24 Reluxation rates of 15% to 71% have been reported with the use of Ehmer slings alone following closed reduction, and reluxation rates are highest if the sling is applied more than 5 days after luxation.43 Cats are often intolerant of slings.19,54 Hobbles.: After closed reduction of a ventral luxation, hobbles may be placed on the hindlimbs (at the hocks or stifles) to prevent limb abduction and maintain joint reduction.15 However, many ventral luxations are managed successfully without hobbles. In a report of 14 dogs with caudoventral hip luxation, 80% returned to normal gait and function after closed reduction alone.60 Ischioilial Pinning.: Insertion of an ischioilial pin (DeVita pin) has been described to stabilize the hip joint after closed reduction.5,17,18,64 A Steinmann pin is placed through a stab incision ventral to the ischium, is passed cranially over the femoral head, and is embedded into the wing of the ilium (Figure 58-5). In cats, the ilial wing is relatively flat, so it can be difficult to properly seat the pin cranially.54 Typically, the pin is allowed to remain in place for 2 to 4 weeks, with exercise restricted for an additional 2 to 4 weeks following removal. A study of 21 dogs with craniodorsal coxofemoral luxation demonstrated that reduction was maintained in 73% of dogs treated with ischioilial pinning; however, the complication rate was 32%.5 Reluxation was less likely when the pin was inserted slightly medial to the lateral eminence of the ischiatic tuberosity and was placed adjacent to the dorsal acetabular rim.5 Inserting the pin at the center of ischium has been shown to result in contact with the sciatic nerve in 75% of cases.39 Complications reported with ischioilial pinning include pin migration, reluxation, sciatic nerve injury, damage to the femoral head, and joint sepsis.5,64 External Fixators.: External fixation (both rigid and flexible) has been described for maintaining joint stability after closed reduction.44 Fixation pins are inserted into the proximal femur and ilium through stab incisions in the skin. The pins are connected externally with bars or flexible bands. The fixator typically remains in place 2 to 4 weeks, with exercise restricted for an additional 2 to 4 weeks following removal. No published studies have described the long-term outcome associated with the use of external fixation for hip joint stabilization. Open reduction of coxofemoral luxations allows exploration of the joint, removal of hematoma and soft tissues entrapped within the acetabulum, and application of internal stabilization. The success rate after open reduction and stabilization (≈85%) is significantly greater than after closed reduction.4,24,43 A craniolateral approach to the joint is usually sufficient for management of craniodorsal luxation; however, a dorsal approach via osteotomy of the greater trochanter or tenotomy of the deep and middle gluteal muscles may be performed to improve exposure. Osteotomy of the greater trochanter allows caudal and distal transposition of the greater trochanter during closure to enhance joint stability.49 For repair of ventral luxation, a dorsal approach to the hip joint is recommended for adequate exposure.29,31,60 After exposure of the joint, soft tissues and hematoma are removed from the acetabulum, and remnants of the ligament of the head of the femur are excised. Damage to the femoral head, acetabular rim, and joint capsule is assessed. The integrity of the joint capsule is evaluated to determine whether it can be primarily sutured to help stabilize the joint. If articular cartilage damage is severe, total hip replacement or femoral head and neck ostectomy should be considered.31,43 Various techniques are used alone or in combination to stabilize the joint while the joint capsule and periarticular soft tissues heal. Techniques described for open reduction and stabilization are numerous and include capsulorrhaphy, ischioilial pinning, prosthetic capsule technique, transposition of the greater trochanter, transarticular pinning, toggle rod stabilization, fascia lata loop stabilization, extra-articular iliofemoral suture placement, transposition of the sacrotuberous ligament, femoral head and neck excision arthroplasty, triple pelvic osteotomy, and total hip arthroplasty.* Selection of the appropriate technique depends on numerous factors, including the patient’s activity level and body weight, the direction of the luxation, the extent of injury to the cartilage and joint capsule, concurrent injuries, economic constraints, and the surgeon’s preference. Capsulorrhaphy.: A craniolateral or dorsal approach to the hip is performed, and the torn joint capsule is sutured to provide joint stability.50 Large, monofilament, nonabsorbable or absorbable sutures are preplaced in the capsule using a horizontal mattress or cruciate pattern, and then tied with the hip internally rotated and abducted. An Ehmer sling may be applied for 10 to 14 days postoperatively to protect the repair. Success rates of 83% to 90% have been reported with use of the capsulorrhaphy technique.4,10 However, in many cases, the joint capsule is too severely damaged to permit adequate closure.43 Alternative methods are required if the joint capsule is severely damaged or avulsed from the femur or acetabulum.

Coxofemoral Luxation

Anatomy

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Diagnosis

Treatment

Closed Reduction and Stabilization

Augmentation of Closed Reduction

Open Reduction and Stabilization

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Coxofemoral Luxation

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue