Chapter 2

Common Pathology and Diseases Seen in Pet Store Reptiles

Species Submitted for Laboratory Evaluation

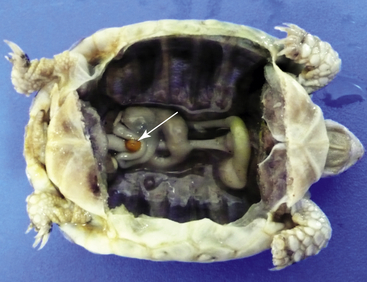

Although many of the lizards and snakes were young animals (evidenced by size and the occasional yolk sac remnants observed on gross postmortem examination), the age of many of the chelonians was not determined (Figure 2-1).

FIGURE 2-1 A yolk sac remnant (arrow) in a young Marginated Tortoise (Testudo marginata), formalin-fixed specimen.

Husbandry-Related Conditions

Deficiencies in husbandry are overwhelmingly the most common factor causing illnesses in captive reptiles. Overcrowding, exposure to sick animals (and their body fluids/excrements), poor nutrition, improper thermal gradients, and many other aspects of reptile care may constitute the basis of many of the illnesses that plague reptiles in the pet trade today (Figure 2-2). Many of the most popular reptiles are shipped to pet stores in containers that are either too small or have too many other of the same (or different) species and minimal, if any, thermal regulation. Many may be shipped from a breeder to a distribution center before being sent to a pet store, and many of these animals (usually younger animals) may not feel like eating for several days during this transition period. The basics of thermal support, humidity, feeding opportunities, hiding options, and a reasonable animal-to-space ratio may not always be provided, even within a pet store setting. All of these factors may trigger new conditions or flare-up of preexisting conditions. Examples may include adenoviral or coccidial infections in Bearded Dragons and cryptosporidial infections in Leopard Geckos.1

When possible, diagnostics should be performed. These should include (but not be limited to) a thorough physical examination, fecal parasite examinations (e.g., direct, float, and/or special stains), laboratory analysis (complete blood count/chemistry profile) and histology/cytology, when indicated (Figure 2-3). Advanced diagnostics including cultures (bacterial and fungal), imaging (e.g., radiographs, ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], and computed tomography [CT]), and molecular testing (including polymerase chain reaction [PCR] testing) may also be indicated. Once a diagnosis is obtained, specific treatments, when available, should be recommended and pursued. While test results are pending, supportive care (including environmental support, fluids, nutritional [caloric and vitamin] support, and antibiotics, among others) should be instituted, as needed.

Common Clinical Diseases

In tortoises, poor nutritional status, failure to thrive, poor shell development, and anorexia are common conditions (Figure 2-4).

FIGURE 2-4 A Slider Turtle (Trachemys scripta) with significant loss of body condition and muscle wasting.

In lizards, parasites include coccidia, pin worms, and protozoans in Bearded Dragons, cryptosporidia are found in Leopard Geckos, and protozoans in most species. Gram-negative enteritis are common in many species. Nutritional secondary hyperparathyroidism (resulting in hypocalcemia and associated changes) is common in iguanas and has also been seen in Leopard Geckos (Figure 2-5). Ocular issues, including conjunctivitis from environmental factors (e.g., reptile bark) or retained sheds (possibly from humidity/hydration issues), are also common (Figure 2-6). Stomatitis is commonly seen in Water Dragons, Blue-tongued Skinks, Bearded Dragons, and Leopard Geckos. Adenovirus in Bearded Dragons may be more common than reported, and concurrent infections with adenovirus and parasites (e.g., coccidia and cryptosporidia) may lead to more severe signs and a greater chance of mortality.2 Failure to thrive, a catch-all term used in captive animals to describe illnesses that are not specifically identified but compromise the animal, is seen in more “sensitive” species (e.g., most chameleon species, some geckos, uromastyx species, and in some areas, water dragons) (Figure 2-7).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree