Chapter 6 Colonoscopy

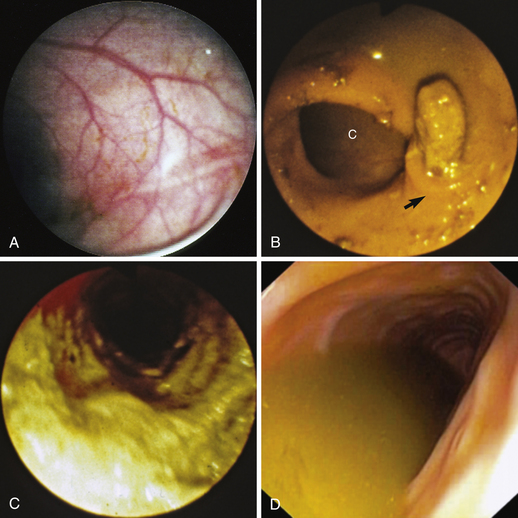

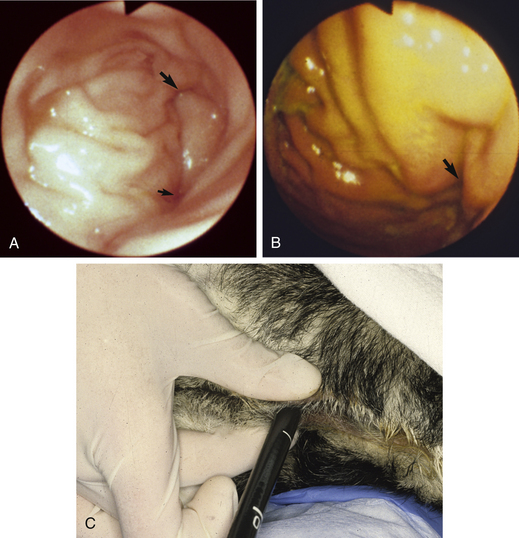

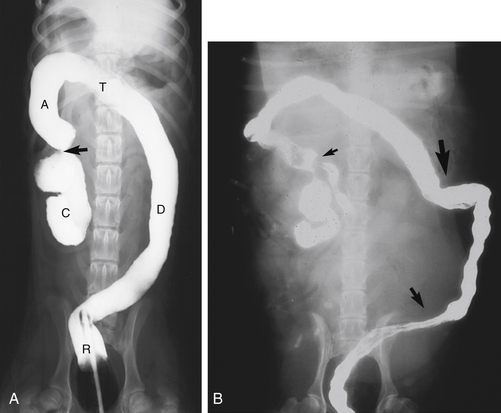

There are many indications for an endoscopic examination of the colon in small animal practice. In my practice, colonoscopy is a safe, minimally invasive, and high-yield diagnostic procedure. Because the large intestine of dogs and cats is simple anatomically (Figure 6-1, A-B, and Figure 6-2), colonoscopy is relatively easy to perform. Clinicians need an appreciation of normal and abnormal endoscopic anatomy, a sound understanding of the colonoscopy technique, and only minimal endoscopic experience to become proficient at performing colonoscopy. The endoscopic techniques described and the photographs contained within this chapter will assist veterinarians in developing sound colonoscopic skills. However, it must be emphasized that colonoscopy must be utilized as part of a rational diagnostic plan for it to effectively help in the diagnosis of an animal’s large bowel problem. Many animals with signs of large bowel disease may not need colonoscopy for an accurate diagnosis to be reached and for appropriate therapy to be administered.

Figure 6-1 A, Ventrodorsal radiograph after barium enema in a dog. R, Rectum within the pelvic canal; D, descending colon, moving toward the left body wall; T, transverse colon, coursing across the abdomen toward the right; A, ascending colon; C, spiral-shaped cecum. The arrow shows the location of the cecocolic sphincter. The flexure between the descending and transverse colon is not as distinct as usual, at an approximate 45-degree angle. B, Ventrodorsal radiograph after barium enema in a dog. The filling of the colon with barium is incomplete. The small arrow shows the location of the ileocolic sphincter. The medium-sized arrow points to a large deflection of the descending colon toward the left body wall from the pelvic canal. The large arrow shows an area of redundancy in the transverse colon. This area could present another flexure to maneuver the endoscope past. Opioid premedication might increase colonic tone and make this area easier to pass the endoscope through (see Figure 6-9).

(A, Courtesy of Dr. Don Barber, Blacksburg, Va.)

Indications

Colonoscopy is an important component of the diagnostic plan for dogs and cats with problems such as chronic large bowel diarrhea, or tenesmus, excess fecal mucus, or hematochezia that accompanies formed feces. Less commonly, colonoscopy may be indicated for animals with obstipation or severe acute hematochezia, with or without diarrhea. Therapeutically, balloon dilation (discussed in greater detail in Chapter 3) of colonic strictures can be performed with colonoscopic guidance. In addition, colonoscopy may be used for therapeutic monitoring of inflammatory and neoplastic colonic disorders.

The most common indication for performing colonoscopy is to grossly and microscopically evaluate the colonic mucosa of dogs and cats with chronic large bowel diarrhea. Clinical signs of large bowel diarrhea include frequent defecation of small fecal volumes, tenesmus, hematochezia, and excess fecal mucus. Weight loss is uncommon. Because there are many causes of chronic large bowel diarrhea (Box 6-1), a thorough and logical diagnostic plan should be followed. An initial diagnostic plan for a dog or cat with chronic large bowel diarrhea should include the following: complete history, thorough physical examination including digital rectal examination, multiple fecal examinations for parasites by a Giardia-sensitive technique, direct saline fecal smear, rectal cytologic analysis, a highly digestible diet trial, and therapeutic deworming for whipworms (dogs).

If fecal examination results are negative and diarrhea does not resolve after the diet trial and deworming, further diagnostic evaluation is necessary. The next step is to perform a fecal enterotoxin assay or treat with amoxicillin, ampicillin, or metronidazole to investigate the possibility of Clostridium perfringens enterotoxicosis. If signs of large bowel diarrhea continue, colonoscopy should be performed. Many of the diseases listed in Box 6-1 can only be definitively diagnosed or excluded by mucosal biopsy. Although full-thickness biopsy samples can be collected via exploratory celiotomy, mucosal samples can be obtained in a much less invasive manner via colonoscopy. Rarely, bacteriologic cultures for Salmonella spp. or Campylobacter spp. or a barium enema is required for diagnosis. Barium enemas are useful in evaluating the cecum and ascending and transverse colons when only a rigid endoscope is available for endoscopic assessment of the descending colon. When a flexible endoscope is available for colonoscopy, a barium enema is not necessary for the diagnosis of chronic large bowel diarrhea.

Colonoscopy permits direct postoperative observation of the sites of submucosal or colonic resection and anastomosis performed to remove tumors. Early detection of tumor recurrence increases the animal’s chances for effective therapy. I recommend surveillance colonoscopy every 3 to 6 months after removal of a malignant colonic tumor. Colonoscopy also allows evaluation of the effectiveness of chemotherapy used to treat colonic lymphoma. Accurate staging of lymphoma by assessment of mucosal biopsy samples during chemotherapy allows for appropriate reduction of the frequency, or termination, of chemotherapy. In humans, malignant transformation of adenomatous polyps occurs. Because the tendency exists for polyps to recur in a susceptible individual, periodic endoscopic surveillance is routinely used to identify and remove additional polypoid lesions before they develop into adenocarcinoma. Although polyps are relatively uncommon in dogs, I recommend colonoscopic surveillance every 6 to 12 months after the removal of an adenomatous polyp.

Instrumentation

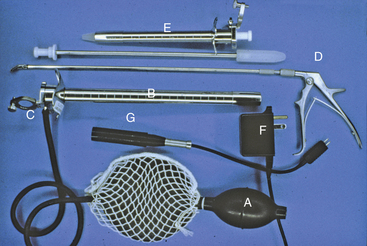

Rigid Colonoscopy

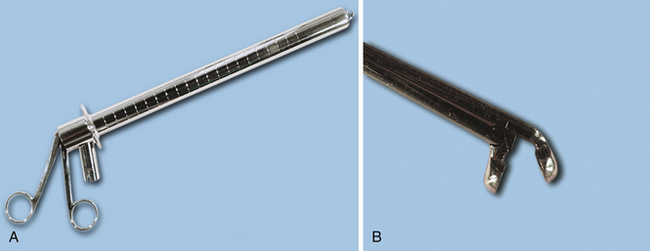

Rigid proctosigmoidoscopes are relatively inexpensive and easy to use (Figure 6-3). They are available in both adult (18-mm) and pediatric (9-mm) diameters, and the latter is particularly useful in cats and small dogs. The maximum length of rigid endoscopes of approximately 25 cm limits examination to the descending colon. However, most inflammatory disorders diffusely involve the colon, so visualization and biopsy limited to the descending colon is usually diagnostic. In addition, many tumors are located within the distal colon and rectum and can be adequately evaluated with a rigid endoscope. Cecal inversion, whipworms, and inflammatory or neoplastic diseases located only in the ascending and transverse colons and the cecum cannot be diagnosed with the use of rigid endoscopy. Rectal or uterine biopsy forceps (especially angulated types) that are longer than the rigid endoscope are suitable for obtaining biopsy samples (Figure 6-4, A-B). Visualization of mucosal detail and biopsy forceps control are not as good with rigid endoscopes as with flexible ones.

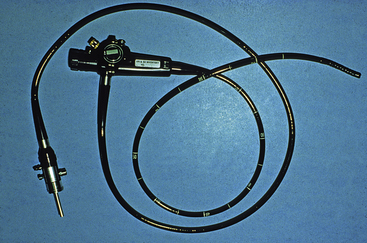

Flexible Colonoscopy

Flexible colonoscopy allows evaluation of the mucosal surface of the entire colon, cecum, and, in some medium or large dogs, the distal ileum. A flexible endoscope with an outside diameter less than 10 mm and a working length of 100 cm is my endoscope of choice for colonoscopy in dogs and cats (Figure 6-5). Occasionally, a 140-cm-long endoscope may be necessary to reach the cecum in giant breeds of dogs. Four-way control of the endoscope tip is vital for making the turns into the transverse and ascending colons. Obtaining adequate size tissue samples for histologic interpretation will be facilitated by a biopsy channel of at least 2.8 mm.

Patient Preparation

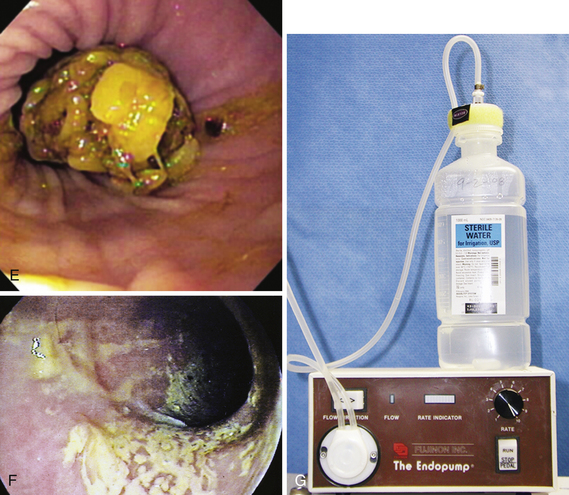

Preparation for rigid colonoscopy requires removal of feces from the descending colon. Fasting and administration of two to three enemas, as described further on, is usually adequate. Proper preparation for flexible colonoscopy requires complete evacuation of fecal material from the colon and production of a clear ileal effluent (Figure 6-6, A-F). Food should be withheld from the animal 24 to 36 hours before the procedure. I administer a high-volume colonic lavage solution (i.e., GoLYTELY, Braintree Laboratories, Braintree, Mass.) and multiple enemas. Colonic lavage solutions are iso-osmotic mixtures of water, electrolytes, and polyethylene glycol. As the gastrointestinal (GI) lavage solution moves through the intestines, there is little net absorption or secretion of fluid or electrolytes. As the solution exits the GI tract, it physically flushes feces and cleanses the colonic mucosal surface. Dogs are given two doses of 60 mL/kg body weight, 2 to 4 hours apart, via orogastric intubation the afternoon before colonoscopy. Cats are given two doses of 30 mL/kg, 2 to 4 hours apart, via nasoesophageal intubation the afternoon before colonoscopy. In addition, a warm water enema (20 mL/kg body weight) should be given after each administration of GI lavage solution, as well as a third enema 1 to 2 hours before colonoscopy. The well-lubricated enema tube should be gently (Figure 6-7) inserted a length equal to that from the anus to the last rib.

Care should be exercised during the administration of the GI lavage solution as aspiration can be fatal. Vomiting or regurgitation of high-volume GI lavage solutions is relatively common in dogs, so veterinarians should be ready to quickly remove an orogastric tube, to allow the dog to expel the liquid from the pharynx and mouth and reduce the chances of aspiration. I do not recommend sedating animals for orogastric or nasogastric intubation because it depresses protective cough and gag reflexes. Aggressive animals or those too difficult to restrain are prepared with three to five additional enemas in lieu of oral lavage solutions. Colonic preparation is often suboptimal in these animals. Vigorous flushing (via an accessory pump attached to the biopsy channel) (see Figure 6-6, G) and suctioning of fluid may be necessary in animals prepared without lavage solutions so that a complete endoscopic examination can be performed. Because of the labor intensity associated with administration of lavage solutions and the potential for aspiration, some practices routinely use only multiple enemas for colonic preparation. In these cases, visualization of the ascending colon and cecum is often reduced, and as already described, additional flushing with an accessory pump and suction is necessary to complete the examination. However, some cats can be adequately prepared with only multiple enemas because of their relatively short colons (see Figure 6-2).

In humans, low-volume hypertonic phosphate solutions have been shown to be as effective for bowel cleansing as high-volume GI lavage solutions. Potential benefits of low-volume preparations include ease of administration, less discomfort, and a greater percentage of patients completing preparation. The hypertonic solution osmotically draws water into the bowel lumen, flushing feces and cleansing the mucosal surface. Hypertonic phosphate solution, 1 mL/kg, was shown to be safe in a group of healthy dogs undergoing colonoscopy, although clinically occult hyperphosphatemia and hypocalcemia occurred. Unfortunately, bowel preparation with and without enemas and bisacodyl was inadequate, and colonic cleansing was inferior to large-volume GI lavage solutions in these dogs (Figure 6-8). Since this study was performed, renal failure has been identified in some humans after hypertonic phosphate bowel preparation. These findings have greatly decreased the use of hypertonic phosphate solutions in humans, especially in the elderly and in those with preexisting renal disease.

Restraint

Sedation or general anesthesia is needed for a thorough colonic evaluation and for minimizing the discomfort and anxiety of the animal. Rigid colonoscopy can often be performed with only chemical restraint (i.e., 0.05 to 0.1 mg/kg IV oxymorphone and 0.05 mg/kg IV acepromazine), although some patients may require general anesthesia. Passage of the flexible endoscope into the transverse and ascending colons and cecum causes stretching of mesenteric attachments, which results in discomfort. Thus, flexible colonoscopy should usually be performed with general anesthesia. I have found that premedication of dogs with opiates may increase colonic tone, making passage of the endoscope through the descending colon easier (Figure 6-9).

Procedure

Rigid Colonoscopy

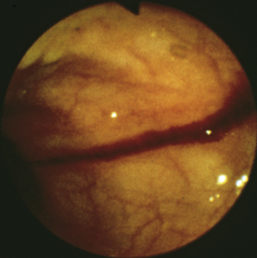

Rigid endoscopes have a smooth obturator (see Figure 6-3, B) that can be inserted to assist the passage of a well-lubricated endoscope through the anal sphincters into the rectum. The obturator should be removed, the viewing lens (see Figure 6-3, C) closed over the end of the endoscope, and the rigid endoscope advanced under direct visualization while the bulb is manually squeezed (see Figure 6-3, A) and air is insufflated into the colon. Advancing the endoscope without a clear luminal view can lead to colonic perforation. Insufflation distends the colon and flattens out mucosal folds, which are most prominent in the rectum and distal descending colon (Figure 6-10, A-B). An inability to distend the colon may indicate severe fibrosis secondary to chronic inflammation or the presence of a stricture. The endoscope should be slowly advanced with constant air insufflation as far into the descending colon as possible, as long as it advances easily. Complete evaluation of the colon is performed as the endoscope is slowly withdrawn. Air must be constantly insufflated to allow clear visualization of the descending colon.

To obtain biopsies, the endoscopist should place the tip of the endoscope within 1 cm of the area to be sampled. The viewing lens should be opened, which allows the colon to collapse as air moves out through the open end of the endoscope. The area to be sampled should be visible at or within the tip of the endoscope. The rigid biopsy forceps are advanced through the endoscope and opened, and the area to be sampled is gently grasped (see Figures 6-3, D, and 6-4, A-B). Before the forceps are completely closed, they should be gently moved back and forth. If only mucosa and submucosa have been grasped, the tissue should be freely movable. However, if the grasped tissue remains firmly attached to the colonic wall, the forceps has gathered muscular layers and colonic perforation is possible. The forceps should be opened, and a new site at least 1 cm away should be selected. Biopsy samples should be collected from visible lesions and normal-appearing mucosa. A minimum of three locations within the descending colon should be sampled.

Flexible Colonoscopy

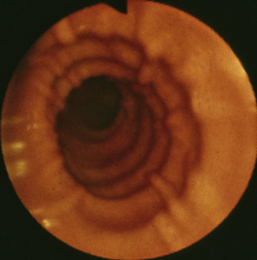

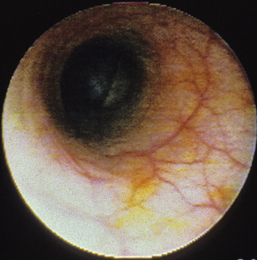

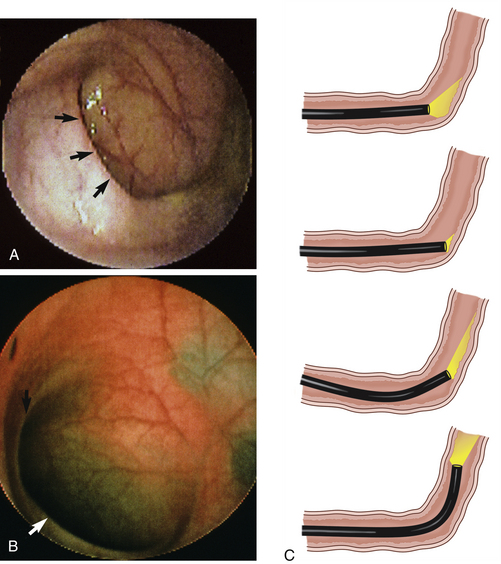

Flexible colonoscopy is performed with the animal in left lateral recumbency. Before insertion of the endoscope a digital rectal examination should be performed to rule out the possibility of a rectal obstruction, mass, ulceration, diverticulum, or perineal hernia, into which inadvertent placement of the endoscope could lead to rectal perforation. The well-lubricated endoscope should be advanced several centimeters into the rectum, air insufflated to distend the colon, and the endoscope advanced slowly as long as a patent lumen can be visualized. An assistant should grasp the perianal tissues tightly around the endoscope to prevent insufflated air from escaping from the colon and to allow the rectal mucosal folds to distend (see Figure 6-10, A-C). Advancement of the endoscope, with a clear view of the center of the colonic lumen, will reduce the possibility for colonic damage or perforation. The central portion of the lumen should be visualized by turning the two angulation control knobs, air should be insufflated to distend the lumen and flatten the mucosa, and the insertion tube should be advanced as long as the lumen is clearly visible. In some locations the endoscope can only be advanced 1 to 2 cm before the central luminal view is lost (Figure 6-11), while in others it may be possible to advance 5 to 10 cm or more. If the central view of the lumen cannot be located, the endoscope should be slowly withdrawn until the lumen becomes visible. Visualization of the central lumen of a long segment of intestines is called a “tunnel view” (Figure 6-12). The three-part philosophy of safe and effective colonoscopy, “centralize, insufflate, and advance,” is repeated as the endoscope is advanced toward the cecum.

Flexible endoscopes have automatic air insufflation, which can be controlled by fingertip pressure covering the opening on the lower button (air/water valve) on the control handle. Insufflation distends the rectum and colon and flattens out mucosal folds, which are most prominent in the rectum and aboral descending colon (see Figure 6-10, A-B). Inability to distend the colon may indicate severe fibrosis secondary to chronic inflammation or the presence of a stricture.

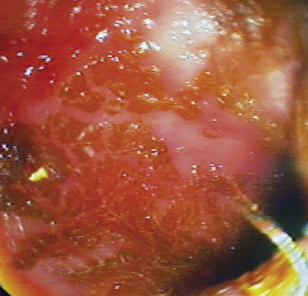

As the endoscope is advanced through the rectum, a partial fold, or flexure, is encountered as the distal colon leaves the midline of the pelvic canal and is located on the left side of the abdomen (see Figures 6-1, A-B, and 6-2). In most animals, advancement past this flexure requires continued air insufflation and a slight directional change of the endoscope’s tip, while in others a maneuver similar to that described further on for entering the transverse colon is necessary. As the endoscope is advanced “up” the descending colon, the splenic flexure (the junction of the descending and transverse colons) is encountered (Figure 6-13, A-B). This flexure represents an approximate 90-degree change of direction as the transverse colon courses across the abdomen from the left to the right side. This junction may be less distinct in cats and some dogs and the angle less than 90 degrees. Continued air insufflation will reduce the angle of this flexure if the endoscopist is patient. The tip of the endoscope should be deflected in a dorsal direction (from the left body wall toward the right), air insufflation continued, and the insertion tube advanced slowly into the transverse colon. The novice endoscopist should determine how to rotate the two angulation control knobs to achieve this 90-degree deflection, straighten the endoscope’s tip, advance the endoscope orad to the flexure against the mucosa (producing a “red out”), angulate the endoscope’s tip as previously memorized, and slowly advance the endoscope into the transverse colon. Visualization of the lumen will be lost for approximately 2 to 4 cm (as the endoscope is against the mucosa, producing a “red out”), but will return as the transverse colon is entered and distended with air. The endoscope should easily slide along the mucosa (Figure 6-13C), and movement should be distinctly visible on the monitor or through the viewing lens. If movement is not visualized or the endoscope does not advance easily, the endoscope should be slowly withdrawn, visualization of the lumen of the orad descending colon reestablished, and the procedure repeated. If, after the transverse colon is entered, a tunnel view of the lumen is not visible and the outer angulation control knob (left/right) is maximally deflected, application of slight clockwise or counterclockwise torque on the insertion tube and control handle will often help obtain a clear luminal tunnel view.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree