Chemical Restraint of Camelids

Unfortunately, things do not always go as planned. Should chemical restraint prove inadequate for the intended procedure, being prepared to convert to injectable or inhalation maintenance anesthesia increases the likelihood of a successful outcome. An anesthetic bolus of intravenous (IV) ketamine may be sufficient for shorter situations. Infusion of Double Drip or Ruminant Triple Drip provides a more stable plane of anesthesia when an extended duration is required. Butorphanol (0.05–0.1 milligrams per kilogram [mg/kg], IV or intramuscular [IM] in llamas and alpacas; 0.02–0.05 mg/kg, IV or IM, in larger camels) or morphine (0.05–0.1 mg/kg, IV or IM) may be administered to augment the level of analgesia of chemical restraint techniques. Onset time for butorphanol and morphine is slow (peak effect is approximately 10 minutes post-IV and 20 minutes post-IM administration). Additional information on these methods is provided in Chapter 46.

Ketamine Stun

The Ketamine Stun is basically the addition of a small dose of ketamine to any injectable chemical restraint technique. I initially developed the Ketamine Stun technique in the early 1990s to cover my limited handling abilities with regard to cats. My first exposure to camelid patients occurred when I left equine practice to teach at Ohio State. Their frequent recalcitrant behavior quickly led to experimentation with low-dose ketamine protocols to improve the level of patient cooperation during diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Success was immediately evident, and the technique became wildly popular with the food animal clinicians, residents, and students charged with the care of these patients.1 Because of the success in camelid patients, the Ketamine Stun technique was adjusted for use in ruminants (lower dose of xylazine) and proved to be just as useful.2 Equine applications have proven more challenging. Dramatic improvement in cooperation evident a minute or two after an IV bolus of ketamine is administered to patients that were totally uncooperative under the prior detomidine–morphine sedation suggests the potential of the Ketamine Stun technique in horses.3,4 Unfortunately, the effective chemical restraint levels of ketamine are not far removed from those that produce instability in horses. The Ketamine Stun technique has been shown to reduce stress response to castration and dehorning in calves.5,6

α2-adrenergic agonists possess potent sedative and analgesic effects. Opioids are typically thought of as analgesic drugs, but they possess central nervous system (CNS) effects, which, when combined with a tranquilizer or sedative, produce a greater level of mental depression. Ketamine is an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist that possesses potent analgesic effects at subanesthetic doses.7 Ketamine was initially included in the stun technique for its analgesic properties but likely contributes to the mental aspects of the enhanced cooperation exhibited by patients under the influence of the Ketamine Stun technique. By combining drugs, smaller doses of the individual components can be used while still achieving the desired level of patient control. Dosing must be more conservative when using the ketamine stun technique in standing patients. This limits the degree of systemic analgesia relative to what can be achieved in recumbent patients but still provides improved patient cooperation when compared with more traditional methods of standing chemical restraint in both ruminants and horses.

In ruminants and camelid patients, I use a combination of xylazine, butorphanol, and ketamine. In equine patients, I use detomidine, morphine, and ketamine. Morphine is used to provide analgesic relief in food animal patients and is much less expensive than butorphanol. I have used morphine (0.05–0.06 mg/kg) in ruminant stuns. In standing adult cattle stuns, a similar level of cooperation is achieved with either opioid, but patients appear less obtunded when morphine is used. Some practitioners may find the obtunded appearance useful because it allows them to monitor decay over time in the level of chemical restraint. Deterioration in the level of patient cooperation also may be used to determine when supplemental drug administration would be required. The systemic analgesia provided by the Ketamine Stun technique is not limited to purely chemical restraint applications. Small doses of ketamine (0.22 mg/kg, IV) layered over a mild level of xylazine sedation provide dramatic short-term (15 minutes) relief from moderate colic pain in horses.8

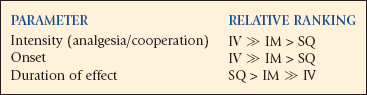

Ketamine Stun techniques can be divided into two broad categories: (1) standing and (2) recumbent techniques. The standing Ketamine Stun is used primarily in large ruminants and horses. The recumbent Ketamine Stun is used primarily in small ruminants, camelids, and foals. The level of effect achieved is determined by three variables: (1) dose, (2) route of administration, and (3) initial demeanor of the patient. The stun cocktail may be administered by the IV, IM, or subcutaneous (SQ) route, depending on the systemic analgesia, patient cooperation, and duration desired (Box 45-1).

Intravenous Ketamine Stun

A combination of xylazine, ketamine, and butorphanol is administered intravenously (Table 45-1). A graceful transition to recumbency occurs approximately 1 minute after IV administration of the Ketamine Stun combination. Patients continue to appear surprisingly “alert” but are typically oblivious to their surroundings and the procedures being performed. Systemic analgesia peaks 1 to 2 minutes after the IV Ketamine Stun administration and diminishes over time. The initial level of systemic analgesia is typically fairly profound. Patients typically are ready to stand and walk with minimal residual effect evident approximately 15 minutes after IV administration of the Ketamine Stun. The clinician should plan ahead and work fast when using the IV Ketamine Stun.

TABLE 45-1

IM, Intramuscular; IV, intravenous.

*Doses of the individual drugs are relatively small, which permits them to be safely rounded up in most instances (e.g., 14 mg becomes 15 mg; 17 mg becomes 20 mg; etc.). Rounding makes drawing doses and the record keeping involved easier. A 1-mL syringe should be used, which requires the use of large animal xylazine (100 mg/mL).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

IM > SQ

IM > SQ IM > SQ

IM > SQ IV

IV