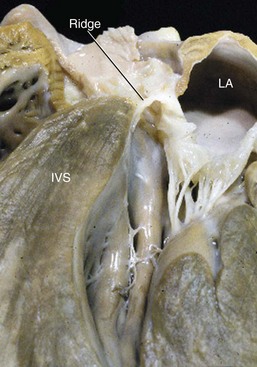

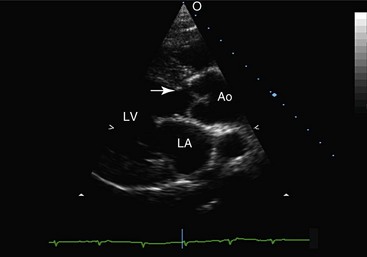

Web Chapter 66 Subaortic stenosis (SAS) resulting from a fibrous lesion that partially or completely encircles the subvalvular outflow tract is one of the most common cardiac malformations in the dog. Planned breeding experiments confirmed that SAS in Newfoundland dogs is heritable (Pyle et al, 1976), and based on observed breed predispositions, it is likely that canine SAS generally has a genetic basis. The severity of the stenosis and associated clinical consequences vary widely. Dogs with severe SAS are at high risk of complications, including sudden death, but mild SAS seldom is responsible for morbidity or mortality. Studies performed during the 1970s confirmed that SAS in Newfoundland has a genetic basis (Pyle et al, 1976). The mode of inheritance was not defined completely, but the results of planned breeding experiments suggest that SAS is either a polygenic trait or an autosomal-dominant trait that is subject to modification by other genes or environmental factors. Recently published data provide evidence that SAS in golden retrievers is familial, although the mode of inheritance was not determined (Stern et al, 2012). There is also evidence that SAS has a genetic basis in Dogue de Bordeaux (Ohad et al, 2013). Because inheritance of SAS is not, apparently, explained by simple Mendelian genetics, dogs with mild SAS may have severely affected offspring. As a result, detection of mild SAS, especially in breeding dogs, is important despite the fact that mild outflow tract obstruction usually does not have clinical consequences. The subvalvular lesion is fibrous or fibrocartilaginous (Web Figure 66-1). In the mildest form of SAS the lesion consists of subvalvular nodules, and these cases may be clinically silent. More severe forms of SAS result in outflow tract obstruction caused by a ridge that partially or completely encircles the subvalvular left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT). The most severe forms consist of plaque or tunnel lesions that involve a large area of the LVOT. Web Figure 66-1 Cardiac specimen obtained from a 6-month-old female rottweiler with severe subaortic stenosis. The specimen was cut through a sagittal plane so that the subvalvular ring (ridge) remained intact. IVS, Interventricular septum; LA, left atrium. In pathologic studies of SAS in the Newfoundland, subvalvular lesions were detected only in pups that were older than 3 weeks. Based on this finding, the lesion responsible for SAS in that breed was judged to be not strictly congenital, but rather acquired, early in life. This observation also has been made in human patients. It has been speculated that the lesion arises because congenital morphologic abnormalities of the LVOT increase shear stress and induce proliferation of cells in the LVOT (Freedom et al, 2005). Recently it was reported that the echocardiographically determined aortoseptal angle in canine patients with SAS exceeds that in unaffected dogs (Quintavalla et al, 2010). A statistical relationship between aortoseptal angle and severity of SAS also was identified. These data are consistent with findings in human beings with SAS but, in the absence of longitudinal studies, it is not certain that the relationship is causal. It is possible that the abnormal outflow tract geometry instead reflects a concurrent anomaly of aortoventricular connection. In the dog, the obstruction may progress for the first 12 months of life; this has important implications for diagnostic screening, genetic counseling, and patient prognosis. In general, dogs with mild or moderately severe obstructions are at low risk of premature death. However, a few dogs in this category develop complications of long-standing SAS, including infective endocarditis and congestive heart failure. Dogs with severe obstruction are at much greater risk of serious sequelae. Sudden unexpected death, presumably the result of lethal ventricular tachyarrhythmia, occurs in the first 2 to 3 years of life in a substantial number of cases (Kienle et al, 1994). SAS is an echocardiographic diagnosis. Except in cases in which balloon dilation is considered, echocardiography essentially has eliminated the need for cardiac catheterization in this disease. The subaortic lesion often can be visualized in moderately or severely affected dogs (Web Figure 66-2). Although the relationship between severity of obstruction and degree of hypertrophy is inconsistent, there often is echocardiographic evidence of concentric left ventricular hypertrophy in patients in which the lesion is visible. Left ventricular systolic performance as evaluated by fractional shortening or ejection fraction is normal to hyperdynamic in most dogs. A few patients, typically those with long-standing SAS, develop ventricular dilatation and evidence of systolic myocardial dysfunction. Web Figure 66-2 Long-axis echocardiogram obtained during diastole from a 4-year-old female rottweiler with moderately severe subaortic stenosis. A subvalvular ridge that is visible on the interventricular septum (arrow) extends to the basilar aspect of the anterior mitral valve leaflet. Ao, Aorta; IVS, interventricular septum; LA, left atrium.

Subaortic Stenosis

Causes

Pathologic Features

Pathophysiology

Diagnostic Approach

Echocardiography

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Chapter 66: Subaortic Stenosis

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue