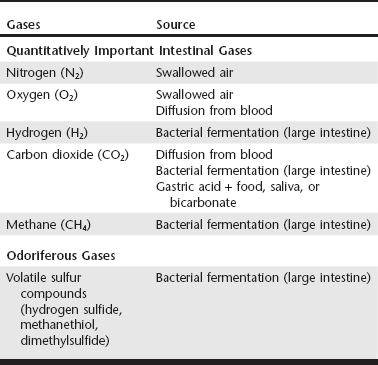

Web Chapter 51 The tendency to treat flatus as a humorous topic has obscured appreciation of the complex physiology that underlies the formation of intestinal gas. The quantitatively important gases in the intestinal tract are nitrogen (N2), oxygen (O2), hydrogen (H2), carbon dioxide (CO2), and methane (CH4). These odorless gases make up more than 99% of the intestinal gas volume in people and pet animals (Web Table 51-1). The characteristic unpleasant odor of intestinal gas comes primarily from the presence of trace gases that contain volatile sulfur compounds such as hydrogen sulfide (H2S), methanethiol (CH3SH), and dimethylsulfide (CH3SCH3). The noxious odor of flatus in humans and dogs correlates most strongly with the concentration of hydrogen sulfide. Gas in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is normal and is derived from four primary sources (see Web Table 51-1): aerophagia (O2 and N2); interaction of gastric acid and alkaline food, saliva, or pancreatic bicarbonate (CO2); diffusion from the blood (CO2 and O2); and bacterial metabolism/fermentation (CO2, H2, CH4, and a variety of trace gases, including volatile sulfur compounds). Gases can be removed from the gut via passage out the esophagus or anus, diffusion into the blood, and consumption by bacteria. The net of these processes proximal to a given site in the GI tract determines the volume and composition of gas passing that site. Pet owners often express concerns with clinical manifestations of flatulence and may describe an increase in frequency of belching, flatus, or borborygmus, objectionable odor of flatus, or abdominal distention. In one study 43% of dog owners reported flatus in their otherwise healthy pet dogs, and 13% of owners reported objectionable odor associated with the flatus episodes (Jones et al, 1998). Dogs housed indoors and less active dogs were more likely to have evidence of flatus. Temperament, frequency of feeding, specific diet, eating habits, age, gender, and history of previous GI disease were not found to be risk factors for flatulence in this study. Belching, abdominal distention, and flatus may develop in conjunction with other GI signs, including weight loss, diarrhea, and steatorrhea. This type of history is suggestive of an underlying small intestinal disorder. Examples of chronic intestinal disorders often associated with flatulence include exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, inflammatory bowel disease, gluten-sensitive enteropathy, food sensitivity, antibiotic-responsive diarrhea, and lymphangiectasia. In one study 26% of cats with chronic diarrhea and/or vomiting had flatus, and 11% of these cats had abdominal distention (Guilford et al, 2001). Cats with clinical evidence of flatulence always should be evaluated closely for underlying chronic GI problems such as inflammatory bowel disease or food sensitivity.

Flatulence

Production of Intestinal Gas

Assessment of Patients with Flatulence

Chapter 51: Flatulence

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree