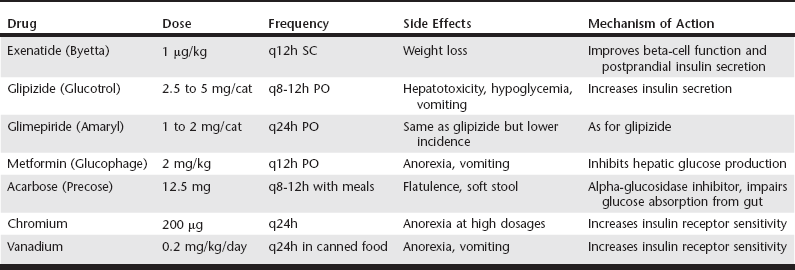

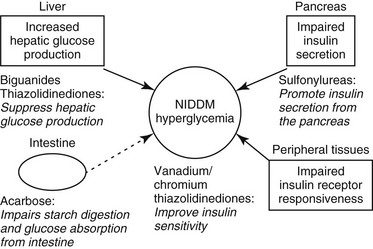

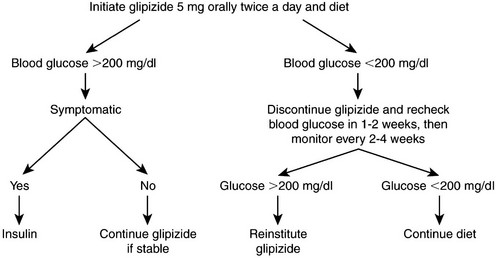

Web Chapter 24 Oral hypoglycemic agents include the sulfonylureas (glipizide, glyburide, glimepiride), biguanides (metformin), thiazolidinediones (e.g., rosiglitazone), alpha-glucosidase inhibitors (acarbose), transition metals (chromium, vanadium), and more recently the incretins (exenatide) (Web Table 24-1). Most of these agents work either by increasing insulin secretion or by decreasing insulin resistance, glucose absorption, or hepatic glucose production (Web Figure 24-1). Indications for noninsulin therapy in cats include normal or increased body weight, lack of ketosis, probable type 2 DM with no underlying disease (e.g., pancreatitis, pancreatic tumor), and in some cases, the owner’s willingness to administer oral medications. Web Figure 24-1 Diagram of the physiologic abnormalities that contribute to hyperglycemia in type 2 DM in humans and cats and the site of action of selected oral hypoglycemic agents. In cats, glipizide has been used successfully to treat diabetic patients at a dosage of 2.5 to 5 mg q12h (see Current Veterinary Therapy XII, p 401, for a full discussion). An outline for monitoring and managing cats undergoing glipizide therapy is shown in Web Figure 24-2. The evaluation of effectiveness should not be made until a cat has been on the drug for 16 weeks, as long as the cat is doing well. Side effects of glipizide include severe hypoglycemia (rare in cats), cholestatic hepatitis, and vomiting. Gastrointestinal side effects, which occur in about 15% of cats treated with glipizide, often resolve when the drug is administered with food (Ford, 1995). The author has noted that use of a lower dosage (2.5 mg/cat) of glipizide is associated with fewer side effects. Furthermore, glipizide does not have a taste; the author has had success adding it as a top dressing to canned food. The next-generation sulfonylurea, glimepiride (Amaryl), has fewer side effects than glipizide and causes less fasting hyperinsulinemia. Web Figure 24-2 Possible clinical consequences of glipizide treatment. (From Ford SL: NIDDM in the cat: treatment with the oral hypoglycemic medication glipizide, Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 25[3]:611, 1995, with permission.) The first long-term prospective study of glipizide in 50 cats studied for 50 weeks showed 35% to 40% initial response rate (after 22 weeks); at the end of the study, seven cats remained regulated on glipizide, six experienced hypoglycemia and were in remission so glipizide was discontinued, six showed initial response but no further improvement in glucose concentrations, and three cats had recurrence of clinical signs that did not respond to further glipizide therapy (Feldman, Nelson, and Feldman, 1997). In a more recent retrospective study of 50 cats on a low-carbohydrate (<10% on a dry matter basis) diet combined with either PZI insulin or glipizide, the response to glipizide was the same as with PZI insulin (about 70% response) (Moeller and Greco, 2005). The difference in response between the two studies may have been the diet the cats were receiving. In the study by Feldman, Nelson, and Feldman, cats were fed a dry or canned high-fiber, high-carbohydrate diet (15% to 40% on a dry matter basis), whereas the cats in the study by Moeller et al were consuming a very low-carbohydrate diet (<5% on a dry matter basis). As in humans, the use of an ultra-low-carbohydrate, high-protein canned diet is the key to success with oral hypoglycemic agents.

Alternatives to Insulin Therapy for Diabetes Mellitus in Cats

Noninsulin Alternatives: Indications

Drugs That Enhance Insulin Secretion

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree