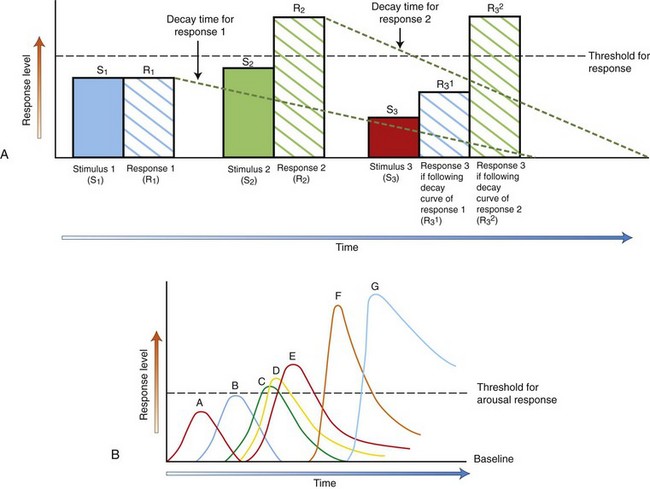

Chapter 3 Thinking About Goals of Treatment The goal of treatment for canine and feline behavioral concerns is a negotiated settlement. Everyone may not get what they want, but everyone can get what they need. This is true whether the behaviors of concern are normal behaviors that the clients dislike or will not tolerate or true behavioral pathologies that put the patient and others at risk. This negotiated settlement is obtained by identifying factors that can be changed through intervention, factors that can be avoided, and factors that require risk mitigation (Box 3-1). • They provide clients with an objective way to see their pets and their concerns. • They form the first step in having someone listen to clients in a non-judgmental, helpful, and empathetic manner. There are two sets of standardized history questionnaires included within this text and on the companion website: long questionnaires for cats and dogs with known behavioral concerns and short questionnaires for cats and dogs to use as routine screening tools at every appointment. There are four required aspects of intervention to facilitate successful treatment as part of a negotiated settlement (Box 3-2). 1. Avoid the circumstances that provoke the behavior from the dog or cat or that are known to be a factor in the pet exhibiting the behavior. 2. Do not punish the dog or cat. Punishment merely tells the pet what not to do and will further raise levels of anxiety and reactivity. 3. Design and implement an appropriate behavior modification plan for that pet in that household using the techniques and strategies discussed later. Essential components of behavior modification include: a. Strategies designed to teach the dog or cat that they are happier and safer if they are calmer and less reactive b. Teaching the pet that he or she can take the cues about the appropriateness of their behavior from you and any normal pets in the household c. Teaching the pet that he or she does not have to react and can instead either avoid provoking situations or respond differently to those situations 4. Praise and reward the dog or cat for any behaviors considered acceptable or good, even if they are normal behaviors and occur when the pet is not interacting with anyone. This is the most important part of treatment, and almost everyone ignores it. 5. Approaches involving clear signaling, positive rewards, and predictable human behavior have been shown experimentally to be superior for training dogs. a. Client reports of their dog’s obedience performance are higher when positive rewards are used (Hiby et al., 2004) and when the methods the clients use are consistent, clear, and reliable (Arhant et al., 2010). b. The ability to learn new tasks—and this is what behavior modification is for most clients and pets—is positively associated with the total rewards (praise, play, treats) that the dog receives and the patience that the client displays while teaching the dog the new behaviors (Rooney and Cowan, 2011). All of these strategies are explained and demonstrated in the accompanying video, Humane Behavioral Care for Dogs: Problem Prevention and Treatment. No! In fact, if everyone in the veterinary practice begins to model their puppy/kitten, new dog/cat, and wellness visits in the manner suggested in Chapter 1, everything that was just discussed can be implemented as a plan to prevent a problem or intervene early in problem development. This is called anticipatory guidance. Anticipatory guidance is used a lot in some human medical specialties, such as pediatrics, but it is underused in veterinary medicine. For a discussion of using this approach with children and dogs, see the “Protocol for Introducing a New Baby and a Pet” and the “Protocol for Handling and Surviving Aggressive Events.” • Every single behavioral condition has a management component as part of the treatment. • Every single behavioral condition can be made worse or better by the manner in which humans interact with the dog or cat and by environmental alterations. • predictability of outbursts, • duration of the condition, and • pattern of the behavioral changes in response to environmental, behavioral, and pharmacological intervention. Of these factors, client compliance may be the most critical. This finding should not be interpreted to “blame” the clients for the pet’s problems. With the exception of abusive or neglectful situations, most canine or feline behavioral problems are not created by people. It is true that people make mistakes, that they do not understand other species, and that it is possible to make any situation worse by inappropriate interventions. However, no study has been successful in showing that pets’ problem behaviors/pathologies are attributable to similar problems in their people (Clark & Boyer, 1993; Jagoe and Serpell, 1996; Parthasarathay and Crowell-Davis, 2006; Voith et al., 1992). Interestingly, studies have shown that people who read their pets’ signals best, best meet their pets’ needs, and find their pets charming and brilliant (Bradshaw and Nott, 1992; Rooney et al., 2001), suggesting a strong and profitable role for the veterinary profession in education of clients. Boxes 3-3 through 3-6 outline good and poor prognosticators for behavioral conditions. Prognosis is best understood if client-driven and patient-driven factors are considered separately. A review of these lists suggests that the rate-limiting step for how well dogs and cats can become is the domain of their humans. Yes. If clients engage in the following behaviors, their pets either will never exhibit behavioral concerns or will start to improve. Depending on the problem, the type of improvement that the clients desire will require more specific and detailed help, but these are three no-fail steps (Box 3-7) that will help in any problem and that will form the basis of all the treatment interventions discussed in this chapter. • Cease all punishment: no yelling, screaming, throwing things or pets, hitting, kicking, smacking, hanging or otherwise “disciplining” of the pet. • Identify situations in which the behavior occurs and avoid those: for example, if the cat uses the carpet only when the litter hasn’t been changed for 2 days, change the litter before 2 days. • Watch for and reward the behaviors that you like and find acceptable: this often means telling the dog or cat that he is wonderful when he is asleep. What Can We Change or Manipulate? These environments are not independent. The extent to which psychotropic/behavioral medication may be warranted depends on the severity of the condition (how abnormal or problematic the neurochemical and behavioral responses are) and the ability to manipulate physical and social environments. Newer behavioral medications allow faster and more effective manipulation of the endogenous neurochemical environment, which helps to shape more appropriate neurochemical and behavioral responses to stimuli in the physical and social environments. • prohibits accurate observation and assimilation of the information presented, • interferes with processing of that information, and • can adversely affect actions taken based on these earlier steps. One should remember that when one diagnoses a problem related to fear or anxiety, one is doing so at the level of the phenotypic or functional diagnosis. Although much treatment and subsequent assessment focuses on changing the non-specific signs apparent at the phenotypic level, if psychotropic medication is used, we are intervening at the molecular and neurophysiological levels (which we then hope will help change the phenotypic level). New evidence about epigenetic effects suggests that effects at the molecular and neurophysiological levels may be governing the signs expressed by which we recognize the condition and the manner in which neurophysiological and molecular effects act (Krishnan and Nestler, 2008; Lubin et al., 2008; McGowan et al., 2009). Anxiety is broadly defined as the apprehensive anticipation of future danger or misfortune accompanied by a feeling of dysphoria (in humans) and/or somatic symptoms of tension (vigilance and scanning, autonomic hyperactivity, increased motor activity and tension) (Overall, 1997, 2005a, 2005b). The focus of the anxiety can be internal or external. For an anxiety or fear to be pathological, it must be exhibited out-of-context or in a degree or form that would be sufficient to accomplish an ostensible goal (Ohl et al., 2008; Overall, 1997, 2000, 2005a, 2005b). The focus on context for the response and degree and form of behaviors informs all of our definitions of canine and feline behavior problems as discussed here. We are quite good about recognizing situational anxiety in dogs where the stimulus is external (e.g., someone leaves the house, the client is out of sight), but we are not good at recognizing anxiety that is internally generated or found to be distressing by the dog (e.g., as in panic disorder, canine post-traumatic stress disorder, or generalized anxiety disorder (GAD); see Chapter 7 for a discussion of these conditions). Given what we now know about canine cognition, we must believe that true endogenous canine anxiety, such as that exhibited by dogs with GAD, occurs and can be recognized on the basis of the behaviors exhibited, across the contexts in which the behavior appears. The conditions specified in the general definition of anxiety should help us frame our criteria for diagnoses of pathological conditions involving anxiety and their assessments. • increased monitoring of the actions of others, • increased or decreased motor activity, with an extreme of freezing, • signs of autonomic hyperactivity (urination, defecation, trembling, shaking, panting), and Neurophysiological signs of anxiety can include (Beerda et al., 1997, 1998, 2000): • tachycardic or bradycardic changes in heart rate (affected by norepinephrine [NE]), • alterations in blood pressure (affected by NE), • vasodilation/constriction (affected by NE), • alterations in gastrointestinal function (which can result in subsequent diarrhea), • changes in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis function including effects of peripheral blood counts (note that chronic anxiety experienced secondary to chronic stress can blunt HPA axis function, which is why “changes” in function are emphasized), • muscle tension and concomitant CK/CPK release (this muscle tension is the cause of dander release and damp fur/paws), and • alterations in sleep and sleep-wake cycles (if the anxiety is long-term). Fear is usually defined as a feeling of apprehension associated with the presence or proximity of an object, individual, social situation, or class of the above (Overall, 1997, 2005a, 2005b). Fear is part of normal behavior and can be an adaptive response. The determination of whether the fear or fearful response is abnormal or inappropriate must be determined by context. For example, fire is a useful tool, but fear of being consumed by it, if the house is on fire, is an adaptive response. If the house is not on fire, such fear would be irrational and, if it was constant or recurrent, probably maladaptive. Normal and abnormal fears are usually manifested as graded responses, with the intensity of the response proportional to the proximity (or the perception of the proximity) of the stimulus in the case of the “normal” fear and disproportionate or out-of-context with respect to the “abnormal” fear. A sudden, all-or-nothing, profound, abnormal response that results in extremely fearful behaviors (catatonia, panic) is usually called a phobia. There are two conditions involving fear that affect many animals and that, when defined, will help in this discussion of treatment (also see the discussion in Chapters 7 and 9). • Criteria: Responses to stimuli (social or physical) that are characterized by withdrawal; passive and active avoidance behaviors associated with the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system and in the absence of any aggressive behavior. Specific behavioral responses include tucking of neck, head, tail and all limbs, hunched backs, trembling, salivating, licking lips, turning away, hiding (even if the only hiding possible is by curling into oneself), averted eyes, et cetera. In extreme cases, urination and defecation are possible. Release of anal sacs may occur. Dander may become apparent, and fur may feel damp. • Notes: Fear and anxiety have signs that overlap. Some non-specific signs such as avoidance (which is different from withdrawal), shaking, and trembling can be characteristic of both. The physiological signs probably differ at some refined level, and the neurochemistry of each are probably very different. It is hoped that refinements in qualification and quantification of the observable behaviors will parallel these differences. • Criteria: Aggression (threat, challenge, or contest) that consistently occurs concomitant with behavioral and physiological signs of fear as identified by withdrawal, passive, and avoidance behaviors associated with the actions of the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system. When these signs are accompanied by urination or defecation or when the aggression is active/interactive (i.e., defensive aggression)—even if the recipient of the aggression has disengaged from or did not deliberately provoke the interaction—the diagnosis of fear aggression is confirmed. • Notes: The actual behaviors associated with fear, fear aggression, and any aggression primarily driven by anxiety (see discussion on impulse control and interdog aggression, for example) are poorly qualified and quantified. In extreme cases, the conditions specified will be clear. If the aggression appears mild, it could be due to uncertainty on the patient’s part. Caution is urged in ruling out all other aggressions. The diagnosis that is most consistent and concordant with signs and criteria should be the one prescribed to the patient. • Fear aggression does not have to occur consistently, although identification of the fearful stimuli will permit assessment of the extent to which the behaviors are consistent and pose a predictable risk. • All of the behaviors associated with fear can occur with fear aggression, but when fear aggression is the consideration, aggressive behaviors usually occur before behaviors associated with extreme distress (urination/defecation/anal sac release, et cetera) occur or as they are happening. • Finally, if the patient is affected by fear aggression, aggressive acts are most likely to occur if the patient is trapped or reached toward or as the provocative stimulus moves away while the patient is moving away and/or attempting to conclude the interaction. 1. “Appeasement” is seldom defined, given the context. A full understanding of risks, costs, and threats would need to be available to define “appeasement.” 2. There may be more parsimonious explanations for the animal’s behaviors that do not require extrapolation of some “emotional” or “motivational” state that is difficult to measure. Message and meaning analysis (Smith, 1977) provides a more discrete, judgment-free, and value-free way of interpreting complex social interactions by allowing us to know, for example, when one participant is signaling their withdrawal. This approach has an advantage over the motivational approach because it is based on behaviors without any assumptions about how these are interpreted by the dog. No one doubts that dogs and cats experience a complete range of emotions, but our attributions about them may be inaccurate, and what we assume to be a “motivation” may not be as important to the dog or cat as it appears to us. If we are really to move into an era of research that maximizes welfare and QoL issues for our patients, we must be cautious about simplistic approaches that make our lives easier but that may not accurately reflect the dog’s or cat’s behaviors and their interpretation of them. Manipulating the physical environment is often overlooked, yet environmental change can often be the first and easiest step in decreasing the patient’s arousal levels. If our goal is to raise the threshold at which the cat or dog displays the signs associated with the diagnosis or the behaviors associated with the client complaint—and these behaviors could be normal—environmental manipulation may be simple and helpful (Fig. 3-1; this figure also appears in Chapter 2). Fig. 3-1 A, The x axis represents time, and the y axis represents response level. R1 shows a response that is proportional to the stimulus—there is no overall behavioral reaction to this stimulus 1 because R1 does not reach the threshold level for the behavioral reaction (horizontal dashed line). The decay time—the time to return to baseline—is shown by the colored dashed curves. At stimulus 2, the summed proportional responses exceed the threshold, and the dog reacts (R2). At stimulus 3, even a small stimulus now causes a worsening in the response (R3) if the patient is still experiencing the R2 decay/recovery response because the responses are additive and the arousal level is still high. However, if the patient experiences stimulus 3 after R1 has sufficiently delayed or recovered, the additive level is not sufficient to trigger a response. This graph illustrates how important multiple stressors and the time over which they are experienced can be for the behavior of the dog or cat. These graphs assume that the threshold level stays the same across time, but with repeated distressing exposures threshold levels for reactivity lower. B, This graph shows how patients with different types of reactivities may respond to the same stimulus and how reactivities can change with time. For simplicity, this graph assumes that the stimulus is the same for each patient, as is the threshold; however, with repeated distressing exposures threshold levels for reactivity lower. • • • • • • • Figure 3-1, A, shows the effect of repeated stimuli, baseline levels of reactivity, and thresholds on the exhibition of behaviors. If the patient is already aroused, a stimulus that would be below the level at which he or she would react may cause reaction. If multiple stimuli are presented to the patient before he or she has returned to baseline levels, they may act additively, causing the patient to react more profoundly or in more situations than that patient would have otherwise reacted. This graph shows how important controlling the stimulus environment can be. If you allow the patient to return to baseline between provocative events, you do not trigger the response. If you continue to force the patient to be exposed to provocative events, the patient reacts to ever higher levels. Because the reaction is profound and the duration of the decay of the response is lengthy (Pitman et al., 1988), you cannot teach appropriate behaviors because the cortisol and epinephrine levels interfere with genetic transcription of information. You can only reinforce fear and avoidance. This application should resonate with veterinarians who have experienced treatment of patients using high levels of restraint. Note that Figure 3-1, A, was developed using only patient A’s response, and patient A is the most normal of the patients. The basal response level or response surface of the patient interacts across time with the intensity and frequency of the stimulus to produce the overall behavioral response. 1. Avoidance allows the dog or cat not to react to something. By not reacting, the patient does not learn with practice how to react more quickly, more frequently, and more intensely. Avoidance means patients do not experience generalization of an undesired response or lowering of the reaction threshold, both of which often occur with practice. 2. Avoidance promotes a level of calm that allows animals to learn new behaviors and responses and to take their cues better as to the appropriateness of their behavior from the context. This type of learning is not possible if the patient is aroused, stressed, or reacting. The physical environment includes: • actual space considerations and the patient’s perception of them, • any visual, olfactory, or auditory stimuli, • any other animals who share the environment, • objects such as litterboxes, beds, and food toys, and • objects that might change the dog’s or cat’s perception, such as curtains or the presence of background music. • Example 1: In a shared, roofed kennel, comfortable, personal/individual doghouses with good visibility can divide the physical space in a way that allows the dogs in the kennel to choose not to interact. The doghouses all provide individual shelter so the dogs are not all crowded in the kennel in one place. As long as no bullies are present, this design can relieve social stresses imposed by group housing. • Example 2: The dog becomes aroused and destroys the mail every day when it is put through the slot in the door. If a mailbox is installed at the fence, the mail carrier does not have to come to the door, and the dog does not become aroused. Also, the dog can no longer destroy the mail. • Example 3: The dog meets the criteria for a diagnosis of territorial aggression and constantly monitors approaches to the house. When a person passes on the sidewalk, the dog begins to snarl and lunge at the window as soon as the person comes into view and continues to react until the person passes from view. A gate could be installed to keep the dog in the back of the house. Opaque film, curtains, or blinds could be installed on the window so the dog could not see the people passing. • Example 4: The client’s cat sits in the window. Whenever she sees the neighbor’s cat come out the cat door and sit in the sun in her own yard, the client’s cat becomes distressed and sprays the window. Closing the door to the room where the window is will not “fix” the cat’s behavioral response, but it will stop it from being triggered. This may be enough of a change for the client. If the cat is otherwise distressed, this is not enough of a change for the cat, regardless of whether the client is content. However, closing the door may help lessen the frequency with which the behavior is triggered, which, when combined with medication, may be sufficient to raise that cat’s reaction threshold. Closing the door also allows the client to avoid having to clean up sprayed urine, which helps the client to understand the cat’s needs separate from her own anger and disgust. • Example 5: The dog meets the diagnostic criteria for and has been diagnosed with inter-dog aggression secondary to GAD and noise phobia. Any loud, echoing noises make the dog more reactive and worsen the GAD. When this happens, the dog threatens his housemates. By having the dog wear Mutt Muffs (www.muttmuffs.com), the overall arousal level is kept low, the GAD triggers are minimized, and the probability of a dog fight is lessened.

Changing Behavior

Roles for Learning, Negotiated Settlements, and Individualized Treatment Plans

Overview

Keys to Successful Intervention and Treatment in a Negotiated Settlement

Do We Have to Wait until the Dog or Cat Has a Problem to Create a Set of Rules for Negotiated Settlements?

Prognoses and Predictors of Outcomes

Are There Any Generalized Instructions That Can Be Quickly Given to Clients When They Express a Concern About Pet Behaviors?

Understanding Behavioral Interventions

Roles for Arousal and Environmental Manipulation

Environmental Manipulation

Physical Environments

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Changing Behavior: Roles for Learning, Negotiated Settlements, and Individualized Treatment Plans