33 Canine uveitis

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

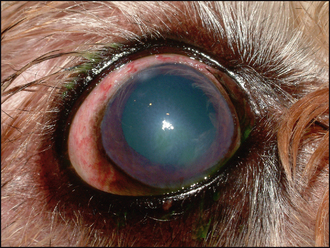

The typical ophthalmic signs of uveitis are episcleral congestion with conjunctival hyperaemia, corneal oedema, miosis and increased lacrimation (see Table 33.1). Pain is normally present such that the examination might be resented. The ocular discharge is usually serous. Vision might be reduced, especially if there is posterior segment involvement. Aqueous flare is often present, sometimes along with frank hypopyon or hyphaema. The iris will be dull and swollen, with rubeosis iridis, although this is quite difficult to appreciate in dogs with dark irides as most do have; however, it is readily noted in blue-eyed dogs. Redness might also be present around the limbus encroaching on the cornea – ciliary flush – or inflammation of the deep episcleral vessels with growth into the cornea (Figure 33.1).

Table 33.1 Ophthalmic signs of canine uveitis

| Acute signs | Chronic signs and complications |

|---|---|

Fluorescein testing should be performed. Usually this will be negative, unless a traumatic incident has occurred or the patient has traumatized the eye secondarily. Measurement of intraocular pressure (IOP) is important and normally readings will be low – commonly 6–10 mmHg. Evaluation of the posterior segment might not be possible. Indirect ophthalmoscopy is likely to be more rewarding than using a direct ophthalmoscope. Mydriasis will assist with fundus examination, but many cases of uveitis will be slow to dilate with tropicamide such that several drops need to be applied over 30–40 minutes before adequate dilation is achieved. Vitreal haze (hyalitis) might be noted along with retinal detachment or areas of active chorioretinitis. These will be seen as dull grey areas within the fundus. Perivascular oedema might be noted as a result of leaky blood vessels. The optic disc is usually normal on examination.

CASE WORK-UP

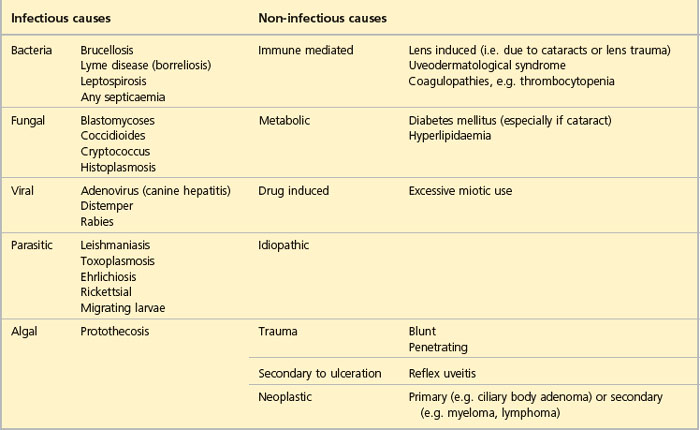

It is the bilateral cases that can be the most challenging to diagnose. Clearly a systemic problem is likely and routine blood screening with haematology and biochemistry profiles are a minimal baseline. These might highlight an infectious aetiology such that more specific diagnostic tests are indicated or suggest a blood dyscrasia or neoplastic process. Generalized septicaemia such as associated with pyometra can cause uveitis. Therefore, the basic screen might suggest that clotting profiles are indicated, or perhaps Toxoplasma, Ehrlichia, Leishmania or Borrelia titres. Mycotic causes for uveitis are rare in the UK but should be considered in immunocompromised patients or those that have travelled through endemic areas. Migrating parasite larvae, such as Toxocara canis, Angiostrongylus vasorum and, less commonly, Dirofilaria immitis, can all trigger an acute uveitis. Faecal examination can be diagnostic in such cases. Some possible causes of uveitis are listed in Table 33.2.

Abdominal ultrasonography is sometimes useful as part of the uveitis work-up – especially if neoplasia is suspected. Most cases of bilateral uveitis which are associated with neoplasia are secondary – lymphoma, myeloma or mammary carcinoma for example.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree