37 Canine intraocular neoplasia

CASE HISTORY

In most cases there is no previous history of ocular disease, or relevant systemic disease.

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

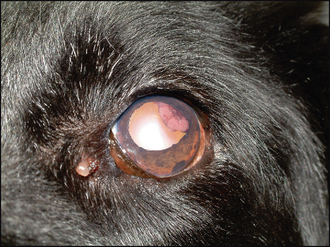

The affected eye might be blind but usually vision is present. Thus a menace response is likely to be normal. Some conjunctival hyperaemia and episcleral congestion might be present but not always. Normally a discoloured lesion will be present. This can be on or in the iris, or behind it poking thorough the pupil. Its colour can vary from dark brown to pale pink and various shades in between (Figure 37.1). The pupil is frequently distorted (dyscoria) but pupillary light reflexes remain. Mild uveitis, with aqueous flare and episcleral congestion, can be present and occasionally the patient is not presented until the eye is painful and enlarged through secondary glaucoma.

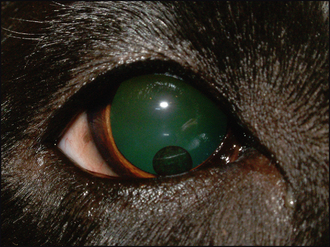

If the neoplasm is based in the iris, then the discolouration will be visible within the iris, and can be raised above it (Figure 37.2). Thus looking at the eye from the side can be useful to determine if the lesion protrudes out from the plane of the iris. Ciliary body-based masses are more difficult to see initially; however, by dilating the pupil the lesion should be more easily visualized through the pupil, especially when looking tangentially across the eye. Vitreal haze is often present with ciliary body neoplasms. Fundus neoplasia is rare but occasionally chor-oidal extension of uveal melanomas does occur.