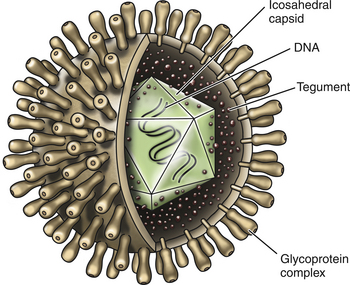

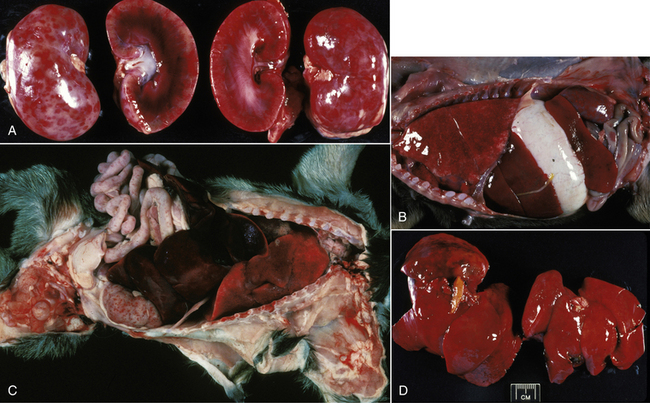

Chapter 16 Canine herpesvirus (CHV-1) is an enveloped virus that belongs to the family Herpesviridae (Figure 16-1). It has been reported from the United States, Canada, Australia, Japan, England, and Germany. CHV-1 was first recognized in the mid-1960s in association with a fatal disease in puppies.2 The virus is commonly blamed for acute neonatal puppy death or failure to thrive, sometimes termed the “fading puppy syndrome.” When confirmed as a cause of disease, untreated CHV-1 infection in neonates can cause high (up to 100%) mortality among littermates. The virus is temperature sensitive and prefers to replicate at temperatures less than 37°C. It is not stable in the environment and is readily inactivated by disinfectants. As with other herpesviral infections, recovery from disease is associated with lifelong latent infection of the neural ganglia, with periodic reactivation of shedding in association with stress or immunosuppression, such as that which results from overcrowding and pregnancy. CHV-1 infection has not been reported in cats. Older (>3 to 5 weeks of age) puppies that are exposed to CHV-1 may develop subclinical infection, or the course of disease is less severe, as a result of their ability to mount a febrile response. Latent infection also may develop. Concerns have been raised about latency and the possibility of late development of neurologic signs.3 The recently infected brood bitch generally shows no clinical signs. Healthy adult dogs of either gender can develop mild upper respiratory signs (sneezing, serous oculonasal discharge, keratitis) for a few days but are otherwise usually clinically unaffected.4–6 Additional information on respiratory and ocular disease caused by CHV-1 can be found in Chapter 17. Tissues obtained at necropsy can be submitted for virus isolation or molecular diagnosis using the PCR. Diagnosis by virus isolation takes days. CHV-1–specific PCR assays can also confirm infection, in a more timely fashion. Clinicians should confirm the availability and turnaround time of commercially available diagnostic tests when attempting to investigate a possible outbreak of CHV-1 infection in puppies.7–9 Gross changes in the kidneys at necropsy of pups infected with CHV-1 include multifocal petechial to ecchymotic subcapsular hemorrhages (Figure 16-2). The pleural surfaces may be mottled pink and red due to coagulation necrosis (Figure 16-2, B). Multifocal random acute necrosis of other organs, including the liver, pancreas, intestine and adrenal glands, may also be apparent. Lesions may resemble those of bacterial sepsis. FIGURE 16-2 A, Kidneys from 12-day-old mastiff puppy from a litter of 17 puppies, 14 of which died. CHV-1 was isolated from the puppy. Gross changes include subcapsular hemorrhagic foci typical of (but not pathognomonic for) herpetic nephritis. On cut section, white and red cortical streaks are evident; a hemorrhagic medulla is evident. B, Multifocal pink and red pleural mottling in the puppy described in A. Serosanguineous pleural fluid was present. Histopathology identified multiple areas of pulmonary necrosis and bronchopneumonia. C, Small-intestinal serosal petechiation in the same puppy. Histopathology identified enterocyte necrosis consistent with CHV-1 infection. D, Liver of the same puppy showing uniform firmness and diffuse mottle with rounded edges. Histopathology identified scattered multiple foci of acute hepatic coagulation necrosis; eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions typical of herpes viral inclusions were seen within viable hepatocytes. (Images courtesy JR Peauroi.)

Canine Herpesvirus Infection

Etiology and Epidemiology

Clinical Features

Diagnosis

Virus Isolation and Molecular Diagnosis Using the Polymerase Chain Reaction

Pathologic Findings

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Canine Herpesvirus Infection

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue