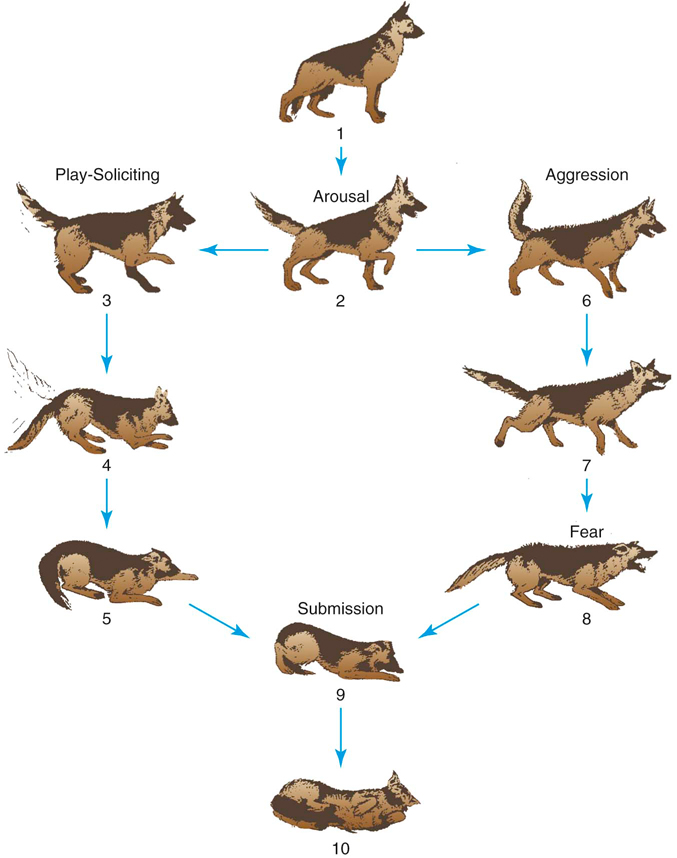

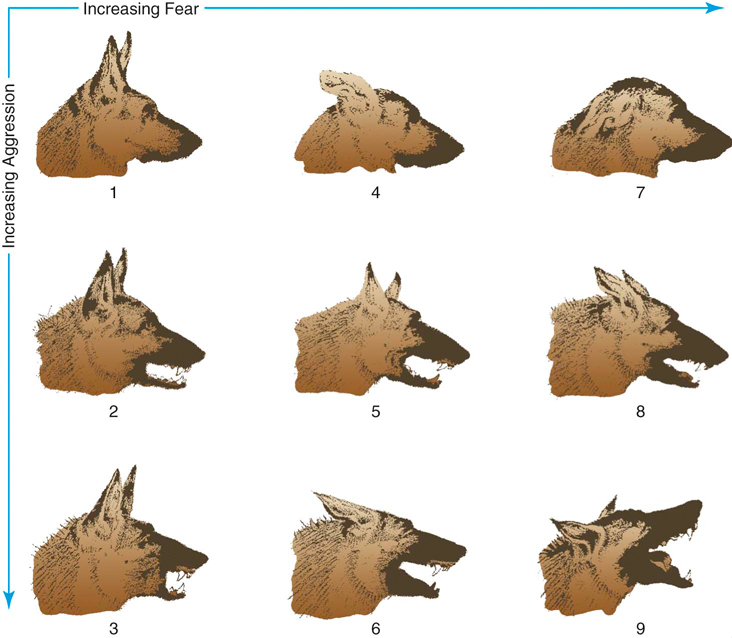

Optimal benefits of physical rehabilitation are achieved with a willing and relaxed patient. An animal that has enjoyable experiences and trusts the handler is more inclined to comply with rehabilitation procedures, which may result in greater success. For example, muscle contraction that occurs in a tense animal is contraindicated during passive range-of-motion exercises.1 Similarly, a patient’s avoidance of aversive handling could interfere with the detection of pain, an indicator of potential tissue damage during cryotherapy2 or neuromuscular electrical stimulation sessions.3 A physical rehabilitation session can subject an animal to potentially painful or frightening procedures that may result in aggressive behavior. Therefore making physical rehabilitation a pleasant experience for the animal can also decrease the risk of injury to the therapist and pet. Pet owners are more inclined to continue rehabilitation if their animals do not appear distressed or hesitant about the facility or personnel. Interpreting body postures and vocalizations in our patients is essential in recognizing fear and stress. Therefore this chapter begins with a basic review of canine and feline communication. Humane handling and behavior modification techniques to decrease fear and ensure a willing patient are also discussed. Body posture and facial expressions are usually the first clue to a dog’s emotional state. Overt postures such as stiff, forward body position with erect ears and tail signal alertness and offensive aggression (Figure 4-1, dog 6). An offensively aggressive dog’s jaw is squared and only front teeth are exposed (Figure 4-2, dog 3). Conversely, a dog that is trembling, in a crouching position, or on its side with its ears and tail tucked is easily recognized as a fearful dog (see Figure 4-1, dogs 4, 5, and 9; Figure 4-3). A fearful or defensively aggressive dog is also lower to the ground compared with assertive dogs (see Figure 4-1, dog 8), often approaches and retreats, and has looser facial expressions that allow all the teeth to be visible (see Figure 4-2, dogs 8 and 9). More subtle behaviors such as panting, lip licking, and yawning can also indicate stress in a dog. During or between procedures, one may notice the dog sitting or lying very still with eyes closed. This is another sign of stress or conflict that may be mistaken for a state of sleepiness or relaxation. While performing potentially painful or threatening procedures, handlers should not only watch for overt body postures, such as lip lifting (snarling), but also less perceptible signals such as an immobilization of the body or a pause in panting. Both of these behaviors may indicate the dog has just become more aroused and aggression may follow. Two actions often misinterpreted are the tail wag and piloerection (or “raising hackles”). Although the tail wag can indicate a friendly dog and piloerection can indicate an aggressive dog, this is an oversimplification. A dog with a loose body posture and low, loose wagging tail may indeed be friendly, but a dog with a stiff body and a rapidly wagging tail, especially if isolated to the tail tip, is probably agitated.4,5 Piloerection is triggered by a sympathetic response and signifies a reactive animal that may be fearful or imminently aggressive. Some contend that hair raised across the entire dorsum may be indicative of the latter and piloerection concentrated on just the dorsal hips or shoulders is a more fear-motivated response.5 Vocalizations are also helpful indicators of a dog’s mood. In general, harsh, low-frequency sounds are an attempt to make the receiver back away, and high-pitched tonal vocalizations are more friendly or appeasing in nature.6 Barking in dogs can convey a wide range of emotions such as alarm, attention-seeking, distress, threat, or warning. A dog distressed by isolation will give a high-pitched bark, whereas alarm or aggressive barks are lower in frequency and harsher sounding.7,8 Aggressive barks are usually given in short, rapid sequence.8 Growling occurs in aggressive and nonaggressive contexts among dogs, but when targeted to humans, growling is typically a low-level threat that can be indicative of defensive or offensive aggression.9 A whine has cyclic frequencies and, in adult dogs, is typically made when the dog is in pain or frustrated.10 Adult dog yelps are barklike and signify similar motivations as whines when directed at humans. Yelps are often heard during situations of greeting, submission, and play solicitation.11 Howling is more common in nondomestic canids species such as wolves and coyotes and occurs as a long-distance call among pack members as a group vocalization to warn an approaching stranger, or possibly to promote pack affinity.12 In domestic dogs, howling may be a response to a sound similar to a howl (e.g., siren or singing owner) and may represent a group vocalization.11,12 In a physical rehabilitation facility, barks or howls may occur as a distress behavior when the dog is isolated in a cage or run. Barks are most commonly excited or aggressive displays in response to the presence of people or other animals. The motivation to vocalize should be reduced to decrease distress in the dogs and also the damage to human and patient hearing. As with dogs, a cat’s vocalizations may help us to recognize its inner state.10,13 The most common and variable vocalization is the meow and is given to seek attention or greet a social partner. A soft, rhythmical murmur is also given during greeting and social interactions. Purring is a unique felid sound that is made by rapid contractions of the laryngeal muscles, innervated by a free-running neural oscillator that contracts and releases every 30-40 milliseconds.14,15 People often assume a purring cat is a content cat, but this behavior can also occur in an anxious, painful, or sick cat. A cat purring during these stressful times is perhaps trying to solicit attention just as the purr from a very young kitten solicits attention from its queen. Aggressive cats may produce loud, harsh howls and growls, as well as hisses and spits. The growl is lower in frequency and longer in duration than the howl. The hiss is an open-mouthed sound invariably displayed in a defensively aggressive cat. During a painful event, a cat may give a loud, quick, high-pitched shriek, probably intended to startle the attacker into release.16 Emotions can also be visually communicated through body and facial postures.5,10,16 A cat with an erect but curved tail, head up, and relaxed ear position is displaying a friendly greeting. Conversely, a cat with a vertically raised, piloerected tail with an arched back, and ears swiveled down or flattened against the head is defensively aggressive. As a cat becomes more frightened, its tail moves into a concave position or is tucked between the legs. An offensively aggressive cat’s tail is lowered, but stiff and lashing. The body appears to be slanting down from tail to head and erect ears rotated back so the inside of the pinna is visible. An offensively aggressive cat’s pupils are constricted but become more dilated with a feeling of fear and defense. Dominance is a description of a relationship between individuals in which agonistic encounters (aggression and submission) establish who has priority to valued items, such as food or mates.17,18 Using dominance as a static attribute of an individual’s personality is incorrect. Dominance and territorial aggression are highly unlikely to be motivators for pets in a therapy facility. This is because they do not have an extended social relationship with personnel, nor have they likely spent enough time in the facility to become territorial. However, frustration and arousal caused by confinement can trigger cage or kennel aggression in an animal distressed by the sights, sounds, and smells of a facility. This is often misidentified as territorial aggression. Fear is the most reasonable impetus for aggression considering the circumstances. Irrespective of an animal’s emotional state, forceful or pain-inducing handling of animals is never warranted and is usually counterproductive.18,19 Harsh methods of restraint can escalate a fear response to fear aggression, causing injury to the pet and handler. Once a pet has a fearful or aggressive response in the facility, subsequent visits will result in an even more extreme reaction, thus preventing the therapist from accurately assessing and performing treatments or exercises. Furthermore, owners will be less willing to bring the animal to the clinic for future treatments because of the animal’s behavior and welfare. Clients will be more likely to endure the inconvenience of bringing a pet to rehabilitation if they feel the pet is being handled humanely and the pet seems to enjoy trips to the clinic. Management of patient behavior begins with an understanding of how an animal learns. Learning is basically how consequences influence behavior and is broadly categorized as nonassociative or associative.20 Nonassociative learning can be further categorized into habituation or sensitization. Operant conditioning and classical conditioning are the two types of associative learning. Habituation occurs when an animal learns not to respond to an inconsequential stimulus on repeated exposures. Flooding is a term often used to describe exposing an animal to a high-intensity stimulus in the hope that the animal will stop reacting. Instead of habituation, sensitization, or an increase in the animal’s reaction to a stimulus, may result. The nature of the stimulus (e.g., loud noise) and the level of stress the pet is experiencing are important factors in determining whether the result will be habituation or sensitization. Furthermore, an animal that is suffering from prolonged distress may experience dishabituation of stimuli and react fearfully toward objects or people to which it previously seemed indifferent.21 Reinforcement or punishment can be further qualified as negative or positive depending on whether something was applied or removed, not the emotion of the animal or trainer. In other words, a positively reinforced behavior is one repeated because the animal previously received something desirable immediately after performing that action. A behavior may also recur because the animal has learned that action will cause something aversive to be removed. This is negative reinforcement. A head halter is often used to decrease pulling on a leash (see Humane Control and Safety Devices later in this chapter for more detailed description). Walking close to the handler is negatively reinforced because the pressure on the nose loop is released when the dog stops pulling and he learns that remaining near the human handler prevents the nose pressure. This is often confused with positive punishment, or decreasing the likelihood of a behavior by inflicting something aversive on the animal after it has performed an undesirable behavior. In the same example, the pulling behavior decreases as the walk proceeds because the dog learns jerking ahead of the handler exacts pressure on the nose. Pulling is positively punished, and remaining near the human is negatively reinforced. A behavior can also become less likely through negative punishment, or removal of something the animal considers rewarding when it performs an unwanted behavior. Most dogs consider their owners’ affections enjoyable so removing this stimulus when the dog is barking or jumping for attention decreases this pestering behavior. The best result comes from well-timed positive reinforcement (giving attention) when the dog is behaving appropriately (sitting) in addition to the immediate negative punishment (removal of attention) of the unruly behavior (jumping). Success of behavior modification depends on the timing and relevancy of the behavior with the punisher or reinforcer. The stimulus must be applied within just a second or two of the animal’s action and be applied consistently for the animal to be able to predict which behaviors elicited the pleasant or unpleasant consequences. Inappropriately applied rewards can result in problems such as rewarding the incorrect behaviors and potentially increasing anxiety. However, poorly applied punishment does not just result in poor efficacy, but also becomes a welfare concern. The inability of an animal to predict and control when it will receive something that induces fear or pain quickly creates a distressed animal. Animals that perceive an aversive event as unavoidable may become apathetic and not attempt escape, a phenomenon called learned helplessness.22 This indifference could be mistaken for relaxation, but short- and long-term activation of the stress neuroendocrine system may lead to compromised health and mental well-being in therapy patients. Positive punishment is often the technique first employed to try to change an animal’s unwanted behavior. However, for the reasons previously discussed, this is rarely appropriate in a clinic or therapy setting. Subjecting an animal to discomfort or verbal reprimand that induces an unpleasant emotional state may suppress behavior (operant conditioning), but also classically conditions fear of the facility and staff. The use of positive reinforcement, negative punishment, and environmental management (e.g., quiet facility and training of staff to correctly read subtle animal body postures) is strongly recommended in a clinic to prevent fear and escape behaviors. The inconvenience, dietary restrictions of some patients, and bias against “bribing” our pets for certain behaviors often limit the use of food in the clinic. Anything the pet finds pleasurable (toy, presence of owner, an activity like “fetch”) can be used as a reward, and thus given as a reinforcer or removed as a punisher. In reality, however, food is an intrinsic need and the most effective, consistent motivator for our patients. Clients can be instructed to consult with a reputable behaviorist or trainer23 regarding the importance of setting behavior criteria and reward schedules to avoid “bribing” for good behavior. But this is of little concern in the clinic because maintaining a relaxed emotional state in an environment fraught with novel and potentially frightening experiences requires a large “pay check” for the pet. If obesity is a concern, the owner can adjust the diet at home to ensure the appropriate caloric intake. Unless a patient cannot be fasted, the owner should be instructed to feed the animal a maximum of half the morning meal; very small treats are provided during the sessions so the pet remains motivated to take the food. A variety of very small treats should be kept on hand in each therapy room. Common favorite foods are real meat or fish, semimoist treats, or sticky foods like peanut butter, meat-flavored baby food, or flavored pastes in nozzle cans.* The food can be used to countercondition or change the animal’s emotional response to the target that elicits fear. As a form of associative learning, counterconditioning can be classical or operant in nature. Classical counterconditioning involves simply providing the dog with rewards in the presence of the fear-producing target with the expectations of replacing the fear response with a pleasant emotion. Often the outcome is more successful if the dog is asked to perform a previously trained command that is incompatible with the fear response while in the presence of the stimulus (operant counterconditioning). Again using the underwater treadmill as an example, a dog that is trembling or attempting to flee as the water fills the chamber could be rewarded for moving forward as the water flow begins by targeting this skill that has been previously mastered outside the apparatus (see Handling of the Physical Rehabilitation Patient later in this chapter). In both classical and operant counterconditioning protocols, the emotional state is being changed. Frequently the target produces such a level of stress that getting the animal focused on a command or a reward may be very difficult. Thus most behaviorists advocate a systematic desensitization protocol in which the animal is habituated to a very low stimulus level (e.g., expose the dog to the treadmill at great distance), and then the intensity level is gradually increased (the dog is brought closer to treadmill) with the goal of never triggering fear. Typically a dog is asked to perform commands for treats as the distance is decreased. This is called a desensitization/counterconditioning protocol and is the crux of most behavior modification.

Canine Behavior

Canine Communication

Figure 4-1 General body postures of dogs. Dog 1 shows a relaxed dog. Dog 2 is alert. Dog 3 shows playful behavior. Dogs 4 and 5 show increasing fear and submission. Dog 6 displays offensive aggression. Dog 7 shows mixed motivations of offensive and defensive aggression. Dog 8 shows defensive aggression. Dogs 9 and 10 show fear and/or submission. (From Overall KL: Clinical behavioral medicine for small animals, St Louis, 1997, Mosby.)

Figure 4-2 Facial postures of dogs. Figures from left to right show increasing fear. Figures from top to bottom show increasing aggressive motivation. Dog 1 is an alert dog. Dog 3 is offensively aggressive. Dog 7 is fearful and/or submissive. Dog 9 is defensively aggressive. All others are intermediate in fear and/or aggression. (From Overall KL: Clinical behavioral medicine for small animals, St Louis, 1997, Mosby.)

Figure 4-3 Fearful dog crouching, furrowing brows, and averting gaze. (Photo used by permission from Yin S: Low stress handling, restraint and behavior modification of dogs and cats, Davis, Calif, 2009, Cattle Dog Publishing.)

Feline Communication

Patient Fear and Aggression during Rehabilitation

Learning and Behavior Modification

Canine Behavior

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Full access? Get Clinical Tree