Breeding Soundness Examination of the Llama and Alpaca

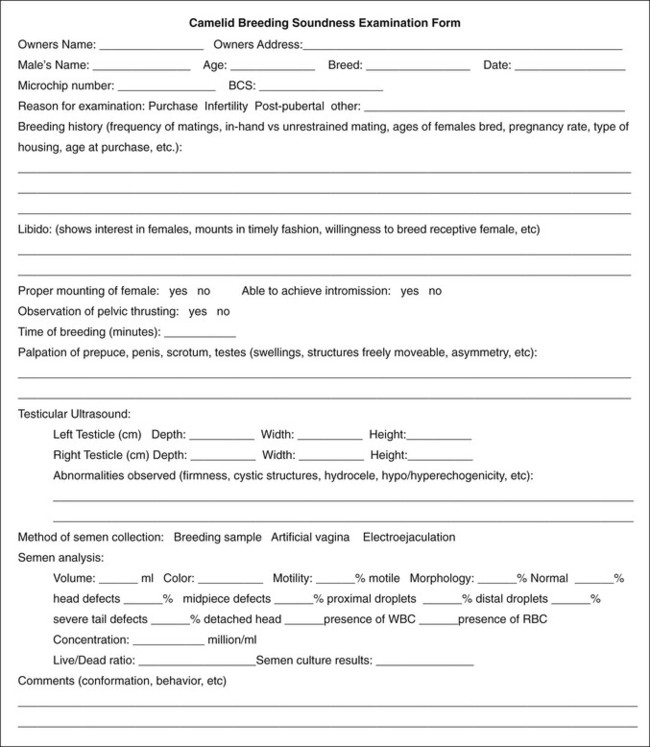

Breeding soundness examination of the male llama and alpaca has become more formalized and better received by clients in recent years because of continuing education programs informing them of the importance and as more literature has documented reproductive pathology and infertility issues. The breeding soundness examination should be performed in a stepwise fashion, making sure to include all parts. This is best achieved by using a form to document the findings (Figure 18-1). Typical reasons for performing a breeding soundness examination would be the purchase of a breeding male, a potential observed infertility (i.e., females not becoming pregnant), or ascertaining the semen production capability of a young male.

Physical Examination

The male camelid should be healthy and sound and in good body condition for breeding. A good body condition score is 2.5 to 3.5 on a scale of 1 (thin) to 5 (fat), or 4.5 to 6 on a scale of 1 (thin) to 10 (fat). The male should be examined using the FAMACHA© scoring system for degree of anemia (caused by parasites) routinely and especially prior to a significant breeding schedule.1 The veterinarian should be familiar with the basic camelid conformation to recognize potentially heritable phenotypic traits during the examination. As an example, a weak back leg structure such as a severe sickle-hocked conformation will result in decreased ability to mount females. Unfortunately, the actual heritability of many of these traits is not well defined. Traits that have been suggested to have some heritability include small and late descending testicles, cryptorchidism, low sperm count and motility, poor fertility, late maturity, large dense lens opacities, abnormal leg angulation, protruding jaw alignment, and disproportioned body frame.

Examination of External Genitalia

Testes

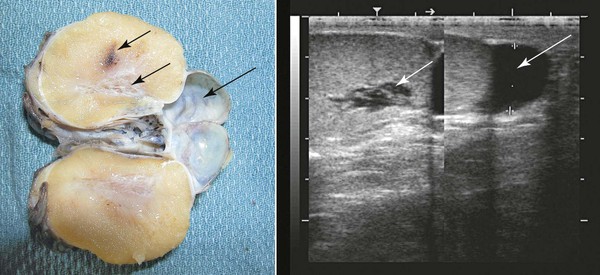

Ultrasonographic examination of the scrotum, testes, and epididymis should be performed on all males presented for a breeding soundness examination. The normal testicle presents a homogeneous, medium-echogenic testicular parenchyma and a more hyperechoic mediastinum testis (Figure 18-2). Cystic structures in or around the testicle that may affect fertility have been documented. Testicular cysts (rete testes cysts, epididymal cysts) may lead to outflow obstructions, resulting in azoospermia or oligospermia (Figure 18-2). Testicular volume is directly related to total spermatozoa production. Ultrasonographic measurements of length, width, and height of testes should be recorded to calculate volume measurement (volume = 0.7 × width rete testes × height rete testes × length; or volume = 0.52 rete testes × width rete testes × height rete testes × length). Most measurements reported in the literature for camelids are for length and width alone. Typical length and width for mature llamas is approximately 5.4 cm × 3.3 cm, respectively.2 Typical length and width for mature alpacas is approximately 3.7 cm × 2.4 cm, respectively.2 In other species such as the horse, expected spermatozoal production may be extrapolated from testicular volume by using a regression equation. This has not yet been developed for camelids. A typical 5-megahertz (MHz) linear array transducer used by many large-animal veterinarians for internal examinations of the reproductive tract may be used to scan the reproductive tract in male camelids. Ideally, a higher-frequency probe may be used (7.5 MHz or higher) to increase resolution of subtle ultrasonographic lesions.

Penis and Prepuce

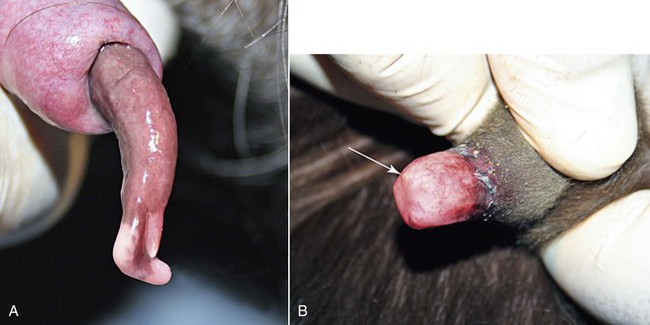

The penis and the prepuce should be visually and manually examined in their entirety. The normal camelid will urinate caudally between the back legs. The preputial opening should be examined for discharges, excess tissue growth, odor, or inflammatory lesions. The penis may be observed by extruding the penis from the prepuce manually. Light sedation will aid in this process. The penis may be stroked within the prepuce to cause the male to straighten the sigmoid flexure. The penis is held still within the prepuce, and the prepuce is reflected back to expose the distal end of the penis (Figure 18-3, A). Gauze sponges (placed around the penis like a catch loop) may be used to hold the penis, as it could be difficult to hold it in extension. Alternatively, the penis may be observed at mating, when the male has mounted the female, although the probing movement of the penis makes it difficult to visualize it without manually stabilizing it. The penis appears darker red in color from blood engorgement directly after breeding. The mucosa should have a uniform surface, with some areas of pigmentation, depending on the color pattern of the male. The penis of the prepubertal male will not be visible in its entirety as the inner prepuce is adhered to the penile skin (see Figure 18-3, B). As testosterone is produced by the testes through puberty, the penis becomes progressively free of the prepuce, which then enables the male to copulate.

Figure 18-3 A, Distal end of breeding male (3 years old). Note the cartilaginous process (large arrow) and the opening of the urethra (small arrow). The penis has a normal slight corkscrew orientation to its long axis. B, Distal end of an immature male (4 months old). Note that the prepuce is adhered to the distal penis, making it impossible to view the penis. The distal urethra (arrow) is just barely visible.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree