Chapter 62 Breed-Related Diseases

Gastrointestinal Tract

In addition to breed predispositions, the medical investigation should always include a problem-solving method. The DAMNIT system of disease diagnosis (Box 62-1) is but one of several pathogenetic methods used in disease diagnosis. The final diagnosis should always explain all of the problems on the problem list, including breed identity. If the final diagnosis is inconsistent with the problem list or breed, the diagnosis may be incorrect, or there may be more than one diagnosis.

Tables 62-1 to 62-6 outline the breed-related diseases of the primary GI tract. Disorders are outlined for each of the segments of the GI tract, for example, oropharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, and anorectum, but it is important to bear in mind that one disease process may affect several segments of the GI tract, particularly those that are contiguous. References for each of these disorders may be found in the literature citations.1–138

Table 62-1 Breed-Related Diseases of the Oropharynx

| Disease | Breed | References |

|---|---|---|

| Cleft palate | English Bulldog, Great Pyrenees, Foxhound, Beagles, Brittany Spaniels, Australian Shepherd dogs | 1–5 |

| Cricopharyngeal achalasia | Golden Retriever | 6,7 |

| Cricopharyngeal dysphagia | Golden Retriever | 8 |

| Eosinophilic granuloma | Siberian Husky, Cavalier King Charles Spaniel | 9–12 |

| Gingival neoplasia | Boxer, Cocker Spaniel | 12,13 |

| Oropharyngeal neoplasia | German Shepherd, Cocker Spaniel, German Shorthaired Pointer, Golden Retriever, Weimaraner | 12,13 |

| Oropharyngeal dysphagia | Bouvier des Flandres | 14 |

| Salivary gland necrosis | Jack Russell Terrier | 15–17 |

| Sialocele | German Shepherd, Miniature Poodle | 18 |

Table 62-2 Breed-Related Diseases of the Esophagus

| Disease | Breed | References |

|---|---|---|

| Esophageal dysmotility | Terrier breeds | 19 |

| Esophageal neoplasia | Irish Setter, Beagle, Pointer Breeds | 20–24 |

| Hiatal hernia | Chinese Shar-Pei, English Bulldog, French Bulldog | 25–28 |

| Megaesophagus | Abyssinian cat, Siamese cat, German Shepherd, Golden Retriever, Greyhound, Irish Setter, Miniature Schnauzer, Wirehaired Fox Terrier | 29–39 |

| Persistent right aortic arch | Boxer, English Bulldog, German Shepherd, Irish Setter | 40–42 |

Table 62-3 Breed-Related Diseases of the Stomach

| Disease | Breed | References |

|---|---|---|

| Chronic hypertrophic pyloric gastropathy | Lhasa Apso, Shih Tsu, brachycephalic breeds | 43–45 |

| Eosinophilic granuloma | Scottish Terrier | 46 |

| Gastric neoplasia | Belgian Shepherd, Chow, Collie, Staffordshire Bull Terrier, Dutch Tervueren, Lundehund | 22, 47–56 |

| Gastric dilation/volvulus | Greyhound, Irish Wolfhound, Blood Hound, Grand Bleu De Gascogne, German Longhaired Pointer, Neapolitan Mastiff, Otterhound, Irish Setter, Weimaraner, Akita, Newfoundland, large and giant breeds, Saint Bernard, Standard Poodle, Great Danes | 57–66 |

| Gastroparesis | Siamese cat | 67 |

| Hemorrhagic gastroenteritis | Newfoundland, Rottweiler | 68 |

| Hypertrophic gastritis | Basenji, Drentse Partrijshond | 69–73 |

| Pyloric stenosis | Boston Terrier, brachycephalic breeds | 74,75 |

Table 62-4 Breed-Related Diseases of the Small Intestine

| Disease | Breed | References |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial overgrowth | Beagle, German Shepherd | 76–79 |

| Cobalamin malabsorption | Border Collie, Chinese Shar-Pei, Giant Schnauzer | 80–83 |

| Eosinophilic enteropathy | Rottweiler | 84 |

| Gluten enteropathy | Irish Setter | 85–90 |

| Lymphangiectasia | Basenji, Lundehund, Yorkshire Terrier | 91–94 |

| Lymphocytic, plasmacytic enteritis | Basenji, German Shepherd | 95–102 |

| Immunoproliferative enteropathy | Basenji | 103 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | German Shepherd, Chinese Shar-Pei | 95–102 |

| Intestinal neoplasia | Siamese cat | 104–106 |

| Parvoviral enteritis | Rottweiler, Doberman Pinscher | 107 |

| Protein-losing enteropathy | Norwegian Elkhound, Soft-Coated Wheaten Terrier, Rottweiler, Yorkshire Terrier | 108–116 |

Table 62-5 Breed-Related Diseases of the Large Intestine

| Disease | Breed | References |

|---|---|---|

| Colonic neoplasia | Mixed breeds | 117–119 |

| Colonic perforation | Dachshund | 120,121 |

| Constipation | Boxer, Manx cat, Siamese cat, English Bulldog | 122,123 |

| Histiocytic ulcerative colitis | Boxer | 124–128 |

Table 62-6 Breed-Related Diseases of the Anorectum

| Disease | Breed | References |

|---|---|---|

| Anal sac adenocarcinoma | Domestic short hair, Cocker Spaniel | 129–131 |

| Circumanal neoplasia | Boxer, Fox Terrier, Cocker Spaniel | 132 |

| Fecal incontinence | English Bulldog, Manx cat | 133–134 |

| Perianal fistulas | German Shepherd, Irish Wolfhound | 135–138 |

Liver and Biliary Tract

The diseases of the liver and biliary tract described in this book (Chapter 61) can be found in both purebred and crossbred animals. A number of these diseases have an increased incidence in certain breeds. In some cases, the inheritance patterns and genetic loci are well understood. In most cases, however, increased breed prevalence is simply an observation in published studies and the underlying genetic basis has not yet been determined. Some breed-related disorders appear to be worldwide in their distribution, whereas others occur only in certain countries or regions, either as a result of different breed genetics in different countries or simply increased recognition in those countries.

It is important to establish clear evidence for increased breed prevalence in liver, biliary, pancreatic, or GI disease. It is all too easy for erroneous data on proposed breed-related disease to become established fact once they are published. Lobular dissecting hepatitis in Standard Poodles is an example where published reports resulted in book chapters and reviews reporting this disease as a breed-related association, even though the original report suggested it may be infectious and not inherited. To ensure that there really is an increased prevalence, and not just a bias introduced by the researcher or local conditions, the prevalence of disease in that breed should be compared to a standard control population such as the normal hospital caseload, Kennel Club, or Cat Fancy registrations in that region, pet insurance, or similar database. Box 62-2 outlines potential reasons for a falsely increased breed prevalence.

Box 62-2

Reasons for a “False” Impression of Increased Breed Prevalence of a Disease

Canine Hepatitis

Canine hepatitis can be classified as acute or chronic and some cases of acute disease progress to chronic hepatitis.1 The majority of acute hepatitis cases are infectious or toxic, but a proportion of cases of copper storage disease in dogs present acutely. Copper storage disease can also be a cause of chronic hepatitis although most other cases of chronic disease are idiopathic. The majority of breed relationships reported are for copper storage disease and chronic hepatitis, and these two conditions are considered separately.

Canine Copper Storage Disease

Pertinent Breeds

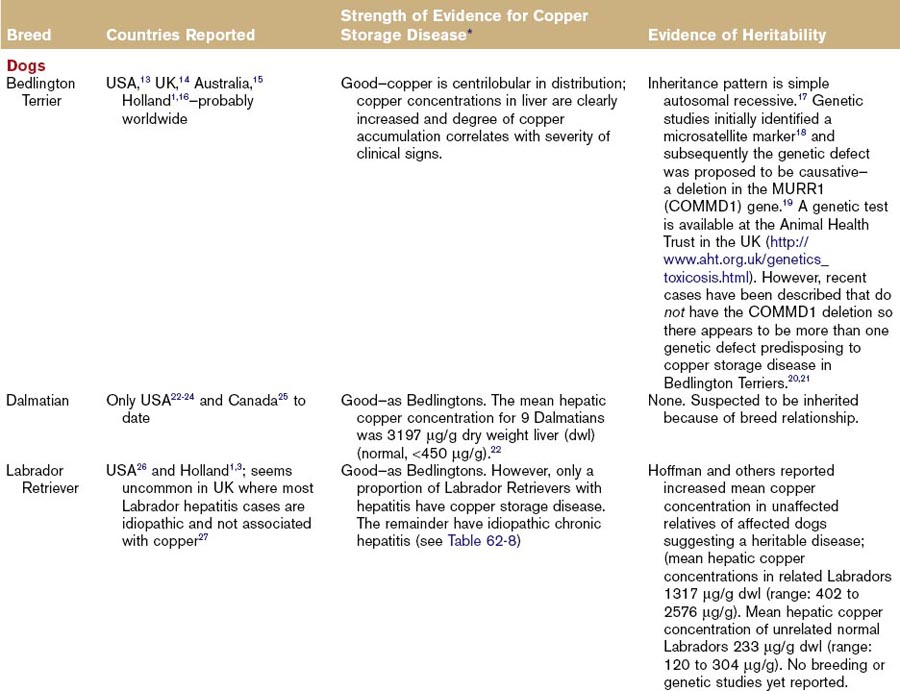

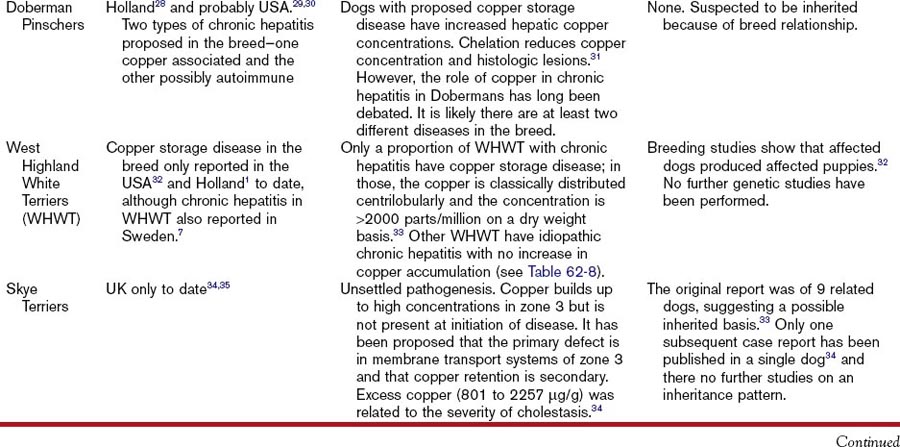

Hepatitis associated with copper storage disease in dogs can be acute, subacute, or chronic, although it is often characterized as chronic hepatitis. The breeds affected with copper storage disease are listed in Table 62-7 along with evidence of heritability. Some of these same breeds are affected by a separate idiopathic chronic hepatitis not associated with copper storage disease (Table 62-8) and there are geographical variations in the relative proportions of each of these diseases (Tables 62-7 and 62-8). Consequently, liver biopsies and copper determinations are very important for effective diagnosis and treatment of hepatitis in these breeds. Bedlington Terriers are the original, and best understood, example of canine copper storage disease, but other breeds have been more recently reported. Copper storage disease has only been reported in a small number of cats (Table 62-7).

Disease Association

Copper storage disease in dogs affects the liver and not other organs, unlike Wilson’s disease in humans, which affects other parts of the body such as the eyes and basal ganglia. In one feline case report, copper was found in the epithelium of the proximal convoluted tubules and collecting ducts of the kidney, and alveolar epithelium and macrophages in the lung.2

Evidence of Heritability

Heritability of copper storage disease has been reported extensively in the Bedlington Terrier and to a lesser extent in the Labrador Retriever and West Highland White Terrier breeds (see Table 62-7). Evidence in other breeds is restricted to isolated case reports (see Table 62-7).

Definitive Diagnosis

In the normal liver, copper is excreted in the bile. Consequently, it can build up in the periportal area (zone 1) secondary to cholestasis. It is important to differentiate this “secondary” copper retention from “primary” copper storage disease where the degree of pathology is directly related to the amount of copper found in the centroacinar area (zone 3). Any breed of dog will show evidence of copper-associated hepatotoxicity if there is a large excess of copper in the diet. What is accepted as a “normal” hepatic copper concentration has increased over the last 30 to 40 years. Increasing reports of copper storage disease in dogs may represent an interaction between genetic susceptibility and dietary copper content. Diagnosis can only be definitively obtained with liver biopsy. Ideally, a large sample (at least 1 g of tissue) should be submitted for copper determination, and histopathology should be performed with a copper stain (rubeanic acid or rhodanine) to show copper distribution in the liver and its association with pathology. If measurement of copper content is not possible, a semiquantitative estimate of copper content can be made with histologic scoring as described by Hoffman and others.3 A genetic screening test is now available for copper storage disease in Bedlington Terriers, but there are inconsistent results in some cases, as detailed in Table 62-7.

Therapy

Copper storage disease can be successfully managed with diet and chelating agents (see Chapter 43), particularly if diagnosed early, or, better still, it can be prevented in susceptible individuals by feeding a low-copper diet from weaning. Chapters 32, 43, and 61 describe the details of therapy.

Idiopathic Canine Chronic Hepatitis

Pertinent Breeds

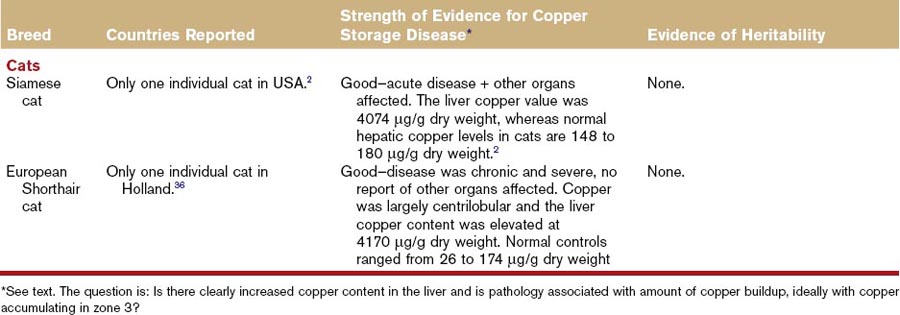

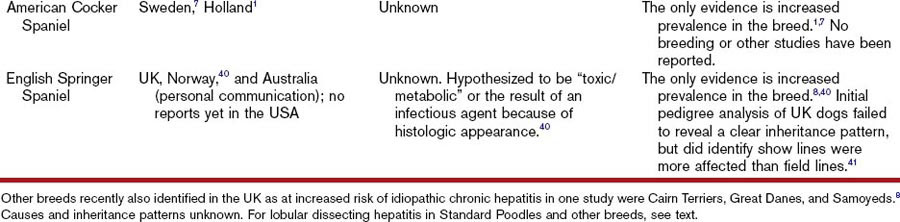

Chronic hepatitis is the most common liver disease recognized in dogs, with a reported prevalence of 12% in older dogs in the United Kingdom.4 The current prevalence in the United States is unknown. In those cases not associated with copper storage disease, the cause remains unknown. It can occur in any breed or crossbreed, but there are reports of increased prevalence in certain breeds as outlined in Table 62-8. These increased prevalences provide opportunities for research in to the cause(s) of this disease, and the causes are likely to be different in different breeds. Table 62-9 outlines the potential reasons for increased breed associations in canine chronic hepatitis, and Table 62-8 details any evidence or suggestions of causes reported in breeds in the literature.

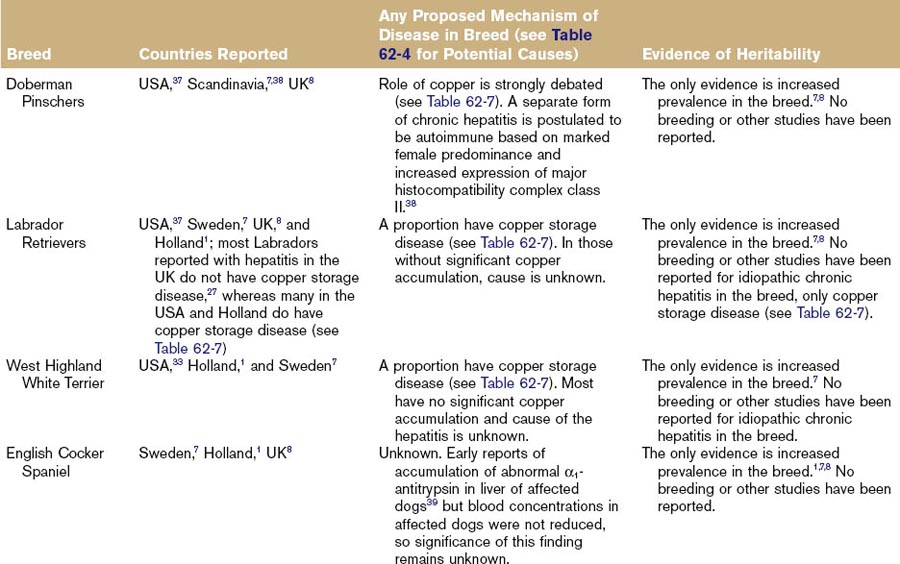

Table 62-9 Potential Reasons for Genetic Susceptibility to Chronic Hepatitis in Dogs

| Genetic Reason for Susceptibility | Examples in Humans | Evidence in Dogs |

|---|---|---|

| Susceptibility to infectious causes of chronic hepatitis and/or to chronicity of infection rather than recovery | Reported nonresponsiveness to hepatitis B vaccine and tendency to chronic carrier state and chronic hepatitis in certain human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles42 | None for hepatitis; some for other diseases, e.g., increased parvovirus susceptibility reported in certain breeds43 |

| Susceptibility to autoimmune disease | Strong genetic predisposition to autoimmune hepatitis in certain HLA classes44 | None for hepatitis; some suspected for other autoimmune diseases45 |

| Mutation of gene coding for protein involved in metal transport/storage/excretion | Wilson’s disease (copper storage disease); also iron storage disease | Copper storage disease in Bedlington terriers; possibly also other breeds (see Table 62-7 for details) |

| Gene mutations resulting in hepatic accumulation of glycoprotein protease inhibitor | α1-Antitrypsin deficiency | No examples; reported α1-antitrypsin abnormalities in Cocker Spaniels are not true deficiency (see Table 62-8 for details) |

| Increased susceptibility to chronic hepatic injury with toxic causes | Genetic susceptibility to alcoholic cirrhosis46 | No clear examples but Dobermans reportedly have impaired detoxification of potentiated sulphonamides47 |

Adapted from Watson PJ: Chronic hepatitis in dogs: a review of current understanding of the aetiology, progression, and treatment. Vet J 167: 228-241, 2004.

Lobular dissecting hepatitis is a histologically distinct form of chronic hepatitis reported predominantly in young dogs, particularly Standard Poodles, Rottweilers, and Mastinos.5,6 This has led to the suggestion of a breed-related disease in Standard Poodles. However, the original authors suggested an infectious rather than inherited etiology6 and the occurrence in litters could be because of environmental rather than inherited factors. Of course, both could interact (an inherited predisposition to an environmental trigger) but the absence of any prevalence data1,7,8 argues more strongly for an environmental cause. Lobular dissecting hepatitis has been reported anecdotally by breeders with increased prevalence in Finnish Spitz dogs in the United Kingdom (personal communication) but no studies have yet confirmed this.

Evidence of Heritability

Most of the published breed prevalence data come from a study performed in Sweden in 19917 that reviewed 299 cases of histopathologically confirmed chronic hepatitis between 1984 and 1989 and compared them with a control population of Swedish Kennel Club registrations. This study found Labrador Retrievers, American Cocker Spaniels, English Cocker Spaniels, West Highland White Terriers, Scottish Terriers, and Dobermans at increased risk of disease. A recent study in the United Kingdom8 that reviewed 4,551 cases of histologically confirmed chronic hepatitis in dogs between 2001 and 2008 compared with a control population of dogs registered by a UK microchip company (175,442 dogs in 2001 and 311,085 dogs in 2008) found overrepresentation of Labrador Retrievers, American and English Cocker Spaniels, Dalmatians, and Dobermans. In addition, English Springer Spaniels, Cairn Terriers, Great Danes, and Samoyeds were significantly overrepresented with idiopathic chronic hepatitis in the UK compared with the control population. A clinical study in Holland of 101 dogs with hepatitis identified a significantly different breed distribution involving English and American Cocker Spaniels, Labrador and Golden Retrievers, West Highland White Terriers, Jack Russell Terriers, and German Pointers.1 The latter study did not separate acute and chronic hepatitis and copper storage disease.

Definitive Diagnosis

Definitive diagnosis of canine chronic hepatitis can only be made on the basis of hepatic histopathology as outlined in Chapters 29 and 61. Finding elevated serum liver enzyme activity and compatible signs on hepatic ultrasound is not sufficient to make a diagnosis, as these findings are very nonspecific and do not differentiate primary chronic hepatitis from other liver pathologies.

Canine Vacuolar Hepatopathies

Vacuolar hepatopathy is generally considered to be a reversible secondary disease characterized by hydropic degeneration of hepatocytes or accumulation of fat or glycogen within these cells (see Chapters 29 and 61).9 These are recognized in a wide variety of breeds and for a variety of reasons,10 but one specific canine breed relationship is currently recognized. There is no reported breed predilection for feline hepatic lipidosis.

Pertinent Breeds

Scottish Terriers in the United States have been diagnosed with a specific type of vacuolar hepatopathy associated with elevated serum alkaline phosphatase activity.10a,10b

Canine and Feline Biliary Tract Diseases

Acute and chronic cholangitis can affect both cats and dogs, but are more common in cats where breed predilections have been suggested for lymphocytic cholangitis. Gallbladder mucocele is recognized in dogs with some suggested breed predispositions but is very rare in cats, where there is no recognized breed disposition. Cystic lesions in the liver in cats are usually biliary in origin and part of an inherited polycystic disease in a number of organs, particularly the kidney. Table 62-10 provides details of known breed relationships in canine and feline biliary tract disease.

Table 62-10 Breed Relationships in Biliary Tract Disease and Gallbladder Mucocele

| Disease: Canine or Feline | Breeds Involved | Evidence of Heritability |

|---|---|---|

| Feline lymphocytic cholangitis | Purebred cats appear to be overrepresented.48 | None except apparent increased prevalence in studies. |

| Feline polycystic disease of liver | Recognized as part of polycystic disease in Persian cats49,50 and also probably Exotic Shorthair cats. Polycystic kidney disease (PCKD) has been reported in these breeds worldwide, including USA, UK, Australia, Italy, France, and Slovenia. | Much evidence for polycystic renal disease (PCKD), which appears to be linked to polycystic hepatic lesions. Persians have an autosomal dominant PCKD51 that was found in 27.5% of Persian and Exotic Shorthair cats tested in one study in the UK and proposed to be the most common inherited disease in cats,52,53 although other genetic forms of the disease are also suspected. |

| Canine polycystic disease of liver | Much less common than cats but reports in Cairn Terriers,54 West Highland White Terriers,55 and Golden Retrievers (where it was proposed to be equivalent to Caroli disease in humans).56 | Evidence in Cairns: one case report of 3 related puppies.54Evidence in West Highland White Terriers from one case report of 7 dogs born from the same parents (2 matings) but none of other relatives suggested autosomal recessive.55 Evidence in Golden Retrievers: one case report of 2 siblings.56 Other large case series fail to show any clear breed prevalence.57,58 |

| Canine gallbladder mucocele | Reported to have increased prevalence in Shetland Sheepdogs in the USA,59 and possibly Cocker Spaniels and Miniature Schnauzers. | High numbers of Shetland Sheepdogs in one published case series.59 Recent study demonstrated a mutation in the gene coding for a phosphatidylcholine transporter was strongly associated with mucocele in Shetland sheepdogs and also 3 dogs of other breeds. Another recent study suggests hyperadrenocorticism is a strong risk factor,60 so some genetic predisposition may be to the underlying cause and not the mucocele itself. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree