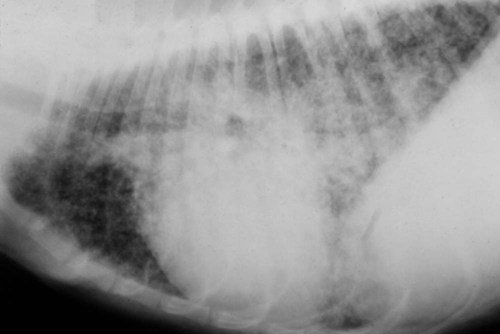

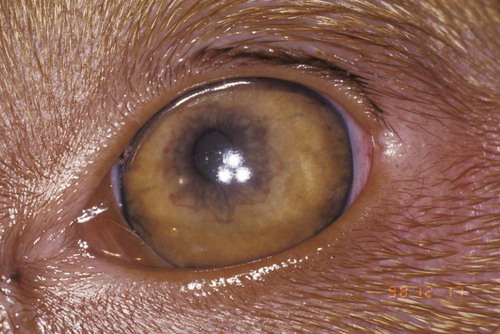

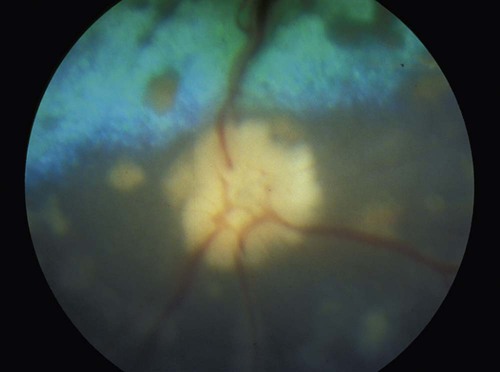

Blastomycosis, as discussed in this chapter, is a systemic mycotic infection caused by the dimorphic fungus Blastomyces dermatitidis. This should not be confused with South American blastomycosis (paracoccidioidomycosis), caused by Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, and discussed in Chapter 60. In nature, Blastomyces grows in a saprophytic mycelial form (Ajellomyces dermatitidis) that reproduces sexually, producing infective spores (aleurioconidia). At body temperature in tissues the organism transforms into the yeast form and replicates asexually. The gene bys-1 controls the change of the fungus from a mycelial to a yeast phase.27 Budding yeasts are 5 to 20 µm in diameter and have a thick, refractile, double-contoured cell wall. Dogs and humans are the most commonly infected with Blastomyces, but cats, horses,102,108 sea lions,113 wolves, ferrets, and polar bears as well as lions and other captive nondomestic felines such as tigers, cheetahs, and snow leopards101 have developed systemic blastomycosis.63,66 Blastomycosis was identified in a rhesus monkey.106 The reservoir for Blastomyces is thought to be the soil; however, recovery of the organism from sites of suspected exposure is uncommon when fungal cultivation has been used.70 Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based methods may make identification of Blastomyces organisms in soil easier.28 Growth of the organism in the environment appears to require sandy, acid soil and proximity to water. Decaying wood by-products and animal waste substrates support growth of organisms.13 Environmental survival of Blastomyces is also restricted because resident soil organisms in most areas destroy Blastomyces inoculated into the soil. A special set of environmental conditions—an ecologic niche—is required for their proliferation. Living near a waterway is a risk factor for blastomycosis infection.83 Organisms were recovered from a beaver dam where numerous schoolchildren were exposed to the organism.60 In Wisconsin studies, 95% of dogs with blastomycosis lived within 400 m (1312 ft) of a body of water at altitudes less than 500 m (1640 ft) above sea level.16,17 The importance of proximity to water also was recognized in a Louisiana study in which dogs with blastomycosis were 10 times more likely to live within 400 m of water than control dogs.2 A study done in an endemic area of Tennessee also recognized the association of clinical disease in dogs with proximity to water but did not find an association with soil type, soil pH, or amount of organic matter in the soil.30 Although proximity to water is a risk factor, exposure to the outside environment is not necessary because blastomycosis can occur in strictly indoor dogs and cats.2,15,20,81 Rain or heavy dew appears to facilitate the release of infectious spores. In one study of 219 infected dogs over an 18-year period, increased rainfall and warmer temperatures preceded the highest incidence periods of infection.15a The seasonal distribution rates of the cases were winter (24%), spring (18%), summer (36%), and fall (22%). Access to sites that have been excavated also increases the risk for infection because of exposure to organisms deep in the soil.16 In humans, involvement in dirt-moving activities significantly increased the risk of developing blastomycosis.81 Even within endemic regions, Blastomyces species are not widely distributed. Most humans and dogs living in such areas show no serologic or skin test evidence of exposure. A point source of exposure within an enzootic area is more likely. For example, it is not unusual to find neighborhoods in which numerous dogs with blastomycosis are identified in a short time. In 14% of households in which blastomycosis has been diagnosed in the humans or dogs, another case is diagnosed in the same household in the next several years.15 Dogs and humans being exposed to a common source of infection while duck and raccoon hunting has been reported.4,91 In other systemic fungal infections such as histoplasmosis (see Chapter 58), coccidioidomycosis (see Chapter 60), and aspergillosis (see Chapter 62) many animals are exposed, but few develop significant disease. However, in canine blastomycosis, subclinical infection is uncommon. When tissues from pound dogs in endemic areas were cultured for fungal organisms, Blastomyces organisms were found in 2%, and Histoplasma organisms were found in 50% of the dogs.103 In contrast, serologic testing for antibodies to Blastomyces may overestimate the prevalence rate of infection. Two of 48 healthy dogs from an enzootic area for blastomycosis had antibodies to Blastomyces according to a radioimmunoassay, but results of an agar gel immunodiffusion (AGID) assay for both dogs were negative.59 The dogs had no history of respiratory disease, which suggested they had a subclinical, self-resolving infection.59 The possibility of nasal colonization with B. dermatitidis as a prelude to lung infection was evaluated with nasal cultures of dogs in a highly endemic area. No organisms were found in nasal swab specimens from 110 clinically asymptomatic dogs.104 Blastomycosis is principally a disease of North America, but it has been identified in Africa, India, Europe, and Central America. In North America, blastomycosis has a well-defined endemic distribution that includes the Mississippi, Missouri, and Ohio River valleys, the mid-Atlantic states, and the Canadian provinces of Quebec, Manitoba, and Ontario (Fig. 57-1)85; however, the distribution may be greater than previously recognized or may be enlarging with sporadic cases in New York.32,37 Occupationally acquired blastomycosis was identified outside the recognized endemic area in two humans from Boulder, Colorado, who became infected by digging to relocate prairie dogs.1,37 Seven dogs with blastomycosis were reported from Colorado State University Veterinary Hospital from 1980 to 1990,87 although the complete travel history of the animals was not available. Pets visiting or hunting in enzootic areas may become infected. Therefore, the areas of risk might be greater than previously recognized. A history of travel to an endemic area should increase suspicion for blastomycosis. Genetic analysis of isolates from soil and human patients has resulted in three isolates—A, B, and C—and each has numerous subtypes.73 All type A isolates were from North America in the upper midwestern states or Canada. B and C isolates were also found in this region, the rest of the United States, and other endemic regions in the world. Genetic identification could discriminate isolated strains for epidemiologic investigations of outbreak sources and the geographic area of infection. Serologic differences in serum antibody responses were found in dogs and rabbits infected with Tennessee and Wisconsin Blastomyces isolates, supporting regional differences in the organisms.5 Most cases of blastomycosis are acquired by inhalation of the spores from mycelial growth in the environment. The spores enter the terminal airway and establish a primary infection in the lungs as a propagating yeast form. When the yeast grows at body temperature, it is too large to enter the terminal airway in an aerosol; therefore, transmission by coughing is very unlikely. Inoculation of Blastomyces into a wound from soil appears to be uncommon in the dog, but in dogs with solitary skin infections without systemic disease, the possibility of direct inoculation cannot be excluded.50,71 Because of the rarity of disease restricted to a focal skin area, cutaneous blastomycosis in the dog should be considered a manifestation of disseminated disease. No breed, age, or sex predisposition for blastomycosis has been recognized in the cat.65 In dogs, males are more frequently infected than females,30 although in a Louisiana study the male/female ratio simply reflected the proportions in the clinic population.2 In dogs with equally severe blastomycosis, a greater percentage of females survived treatment in one study,69 but in another study no differences in survival were found.2 An epidemiologic study using the Veterinary Medical Data Base (Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN) identified sporting dogs and hounds to be at greater risk for blastomycosis.87 This finding was attributed to outdoor activity as a risk factor for developing blastomycosis, but as mentioned previously, blastomycosis also develops in strictly indoor dogs and cats.15,20,20 Many of the sporting breeds are brought to high-risk areas to hunt. Certain nonsporting breeds such as Doberman pinschers were also at increased risk.2,64,64 Whether the risk in this breed can be attributed a genetic immune deficiency is uncertain. In general, large-breed dogs are more commonly infected than small-breed dogs. This finding also may reflect increased exposure from outdoor activities and roaming in larger dogs. The highest prevalence is in 2-year-old dogs; most infections develop in dogs 1 to 5 years of age. No seasonal differences in disease are found in Tennessee, but more cases occur from late spring through late fall in Wisconsin.3 In Louisiana, more cases were reported in August, September, October, and January than in the rest of the year.2 After a Blastomyces infection becomes established in the lungs, it disseminates throughout the body. The preferred localization sites of infection in the dog are the skin, eyes, bones, lymph nodes, subcutaneous tissues, external nares, brain, and testes. Less commonly affected sites are the mouth, nasal passages, prostate, liver, mammary gland, vulva, and heart. Intestinal lesions have rarely been found in dogs with systemic disease.8,78 Dissemination is thought to occur via vascular and lymphatic routes. Although organisms enter the lung in almost all cases, lung lesions may resolve by the time the sites of disseminated infection become apparent. Occasionally, a focal lesion develops from a puncture wound,50,71 but generally a solitary lesion should be considered part of a systemic process. Distinct species differences in susceptibility to Blastomyces seem apparent. The dog appears to be more susceptible to infection than people, and in enzootic areas of Arkansas and Wisconsin, the incidence of blastomycosis is 10 times higher in dogs than in people.11,16 The incidence in dogs was 1420 per 100,000 dogs per year.16 Young age and close proximity to a shoreline were risk factors.18 Dogs appear to have a shorter prepatent period and tend to develop the disease more quickly than humans when exposed at the same time.91 Dogs may inhale a larger inoculum of organisms than humans because they are closer to the ground. Their nasal passages are also more efficient at trapping inhaled organisms. Larger doses of inoculum cause the disease to progress faster and death to occur sooner.107 The pathogenicity of isolated strains varies considerably.77 Cats are not commonly infected with Blastomyces. A 5-year survey of the Veterinary Medical Data Program identified three infected cats, whereas 324 dogs with blastomycosis were found.5 Reports of multiple cases of blastomycosis in cats suggest that it may be more common than previously appreciated and possibly underdiagnosed.20,44 An effective immune response to Blastomyces requires a T-lymphocyte, cell-mediated immune response directed partly to a surface adhesion virulence factor Wisconsin 1 (WI-1), now called Blastomyces adhesion 1 (BAD-1) antigen.57 The BAD-1 antigen is an important virulence factor that depresses the production of tumor necrosis factor-α, which is important for phagocyte killing of the Blastomyces organisms and recovery from blastomycosis.23,40,40 Antibodies against the WI-1 antigen produced no protection against infection in a mouse model,112 a finding that is consistent with high antibody concentrations specific for Blastomyces organisms in dogs with life-threatening, progressive blastomycosis. A majority of dogs experimentally infected by exposure to contaminated soil recover from blastomycosis without treatment.98 It is likely that when naturally exposed, some dogs develop mild respiratory signs and recover spontaneously. Antibodies in 2 of 48 healthy dogs from an endemic area with no history of illness suggest that occasionally dogs do develop a subclinical, self-resolving disease.59 However, almost all dogs with clinical signs that have warranted veterinary attention have disseminated disease and should be aggressively treated. Dogs2 and humans90 occasionally recover from symptomatic blastomycosis without treatment. A majority (85%) of dogs with blastomycosis have lung lesions with characteristic dry, harsh lung sounds. Dogs with mild lung disease show exercise intolerance, and severely affected dogs have dyspnea at rest. Coughing is a variable finding. Thoracic radiographs are indicated for dogs suspected of having blastomycosis because some dogs have lung changes without respiratory signs. On radiographs, diffuse, nodular interstitial and bronchointerstitial lung changes are common findings (Fig. 57-2). In a review of the pulmonary changes in blastomycosis, over 50% of the dogs had nondiffuse infiltrates with an alveolar pattern, a mass pattern, a large interstitial pattern, or a combination of these radiographic changes.34 Other less common manifestations include well-marginated solitary to multiple cystic or solid nodules or masses. Retroperitoneal pyogranulomatous and fibrosing inflammation has been observed.31b Tracheobronchial lymphadenomegaly develops in about 25% of dogs.34 Pleural effusion and pneumomediastinum are also observed. Pulmonary bullae were present at the time of diagnosis in about 5% of dogs, but bullae developed in over 15% of dogs during therapy. The bullae were usually associated with current or resolving alveolar infiltrates.34 Chylothorax and solid fibrous masses are uncommon manifestations of thoracic blastomycosis. Solid fibrous masses may partially occlude the great vessels. An obstructive anterior vena caval syndrome and granulomas that were induced by Blastomyces and caused chylothorax were diagnosed in a young dachshund.52 Pulmonary thromboembolism secondary to blastomycosis can increase the degree of dyspnea that develops with the fungal pneumonia.74 Up to 40% of dogs with blastomycosis have ocular lesions, the most common of which is uveitis. Early signs of uveitis are conjunctival hyperemia, iridic hyperemia, aqueous flare, and miosis (Figs. 57-3 and 57-4). Chorioretinitis (Fig. 57-5), optic neuritis, retinal detachment, retinal granulomas, vitritis, and vitreal hemorrhage are also caused by blastomycosis. Severe corneal edema may prevent good visualization of the internal ocular structures. Glaucoma secondary to angle closure also develops.21 Lens rupture occurred in 40% of eyes with endophthalmitis requiring enucleation. The lens material probably contributed to cataract formation and ocular inflammation.51 Panophthalmitis with associated orbital inflammation is common in severe ocular disease. Keratitis, conjunctivitis, and inflammation of periorbital tissues are frequently observed. Reviews discuss the spectrum of lesions and specific therapy for blastomycosis in the eye.39,62 Uveitis in conjunction with signs of respiratory or skin disease should alert the clinician that an animal may have blastomycosis. Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment are essential to preservation of vision in blastomycosis (see Ocular Infections, Chapter 92). Skin lesions, found in 20% to 50% of dogs with blastomycosis,2,63,63 may be ulcerated with drainage of a serosanguineous or purulent fluid. Other lesions may be granulomatous, proliferative, and meaty. Well-defined subcutaneous abscesses may develop. Calcinosis cutis developed in three dogs during amphotericin B (AMB) treatment.48 The lesions resolved completely after the completion of treatment. Although the skin lesions may be found anywhere, the planum nasale (Fig. 57-6), the face, and the nail beds (Fig. 57-7) appear to be preferred sites. Bone involvement occurs in up to 30% of infected dogs. Lameness is the primary sign in affected animals and may be the only sign of disease. Special procedures, such as bone scans, may identify a greater percentage of dogs with bone involvement. Lesions usually involve the appendicular skeleton and are typically osteolytic with periosteal proliferation and soft tissue swelling (Fig. 57-8). A majority of the bone lesions are solitary and develop distal to the stifle and elbow. Fungal osteomyelitis must be differentiated from primary and metastatic bone tumors and bacterial osteomyelitis. Various other tissues may be less commonly infected, including testes, prostate, kidney, bladder, brain, mammary gland, joints, heart, and nasal passages.2,63,66,104,105 The testes and epididymis may be greatly enlarged and painful. Involvement of the prostate gland produces swelling and pain. Dogs with involvement of the kidneys, bladder, or prostate may have organisms in the urine. Meningeal and secondary brain involvement usually develops with widely disseminated disease but may develop without multisystemic manifestations. Depression, seizures, and neurologic deficits are noted with central nervous system (CNS) infections. Nasal discharge and obstruction of airflow through the nose develop when blastomycosis involves the nasal passages.105 Cardiovascular granulomas due to blastomycosis produce myocarditis, heart block, murmurs, pericarditis, arrhythmias, syncope, and heart base and intracardiac masses.93 Lesions have been found in most organs of infected dogs. Blastomycosis of the gastrointestinal tract is rare but was identified in two dogs with generalized blastomycosis.8,78 Cats with blastomycosis have lesions similar to those of dogs, but too few cats have been evaluated to derive a reliable characterization of predominant signs. Dyspnea, increased bronchovesicular sounds, visual impairment, draining skin lesions (Fig. 57-9), and weight loss have been the most frequent findings.44 Eye involvement generally produces a pyogranulomatous uveitis.45 Intracranial CNS disease and posterior paralysis also have been reported.76,99 Clinical signs reflect the involved tissues: lung, lymph node, kidney, eye, CNS, skin, gastrointestinal tract, pleura, and peritoneum.76 Radiographic and ultrasonographic procedures are valuable in detecting fungal lesions in many organs. Contrast-enhanced computed tomographic imaging of the brain has been used to identify lesions in a dog with CNS blastomycosis.88 Magnetic resonance imaging can be used to detect granulomas in various organs including the CNS.69a Sites of Blastomyces infection in dogs can be identified using positron emission tomographic imaging.72 This is a very sensitive technique but unfortunately is not widely available for veterinary diagnostics. On preliminary laboratory evaluation, a mild normocytic, normochromic anemia develops that can be attributed to chronic inflammation. Most dogs have a moderate leukocytosis (17,000 to 30,000 white blood cell count per microliter) with a mild left shift, and lymphopenia is common. They usually have hyperglobulinemia and hypoalbuminemia. The increased globulin concentrations are caused by an increase in α2-globulin and a polyclonal increase in immunoglobulins. The only other biochemical change that may be seen is hypercalcemia of granulomatous disease (total [bound plus ionized] serum calcium = 12.5 to 17.5 mg/dL), which may occur without bone lesions.38 Twelve of 87 dogs with blastomycosis had total hypercalcemia, but the increase was less than 13.4 mg/dL in all but one dog, which had a 16.8 mg/dL increase in total serum calcium.2 Serum ionized calcium concentrations were more accurate than total calcium in determining increase in functional (“true”) calcium concentrations with only 2 of 38 dogs with blastomycosis being truly hypercalcemic.36 Increased serum calcium concentrations (total and ionized) return to reference ranges after treatment. Hypercalcemia may be associated with renal failure.

Blastomycosis

Etiology

Epidemiology

Natural Reservoir

Geographic Distribution

Mode of Infection

Pathogenesis

Host Signalment

Dissemination of Organisms

Host Response

Clinical Findings

Dogs

Cats

Diagnosis

Medical Imaging

Clinical Laboratory Testing

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Veterian Key

Fastest Veterinary Medicine Insight Engine