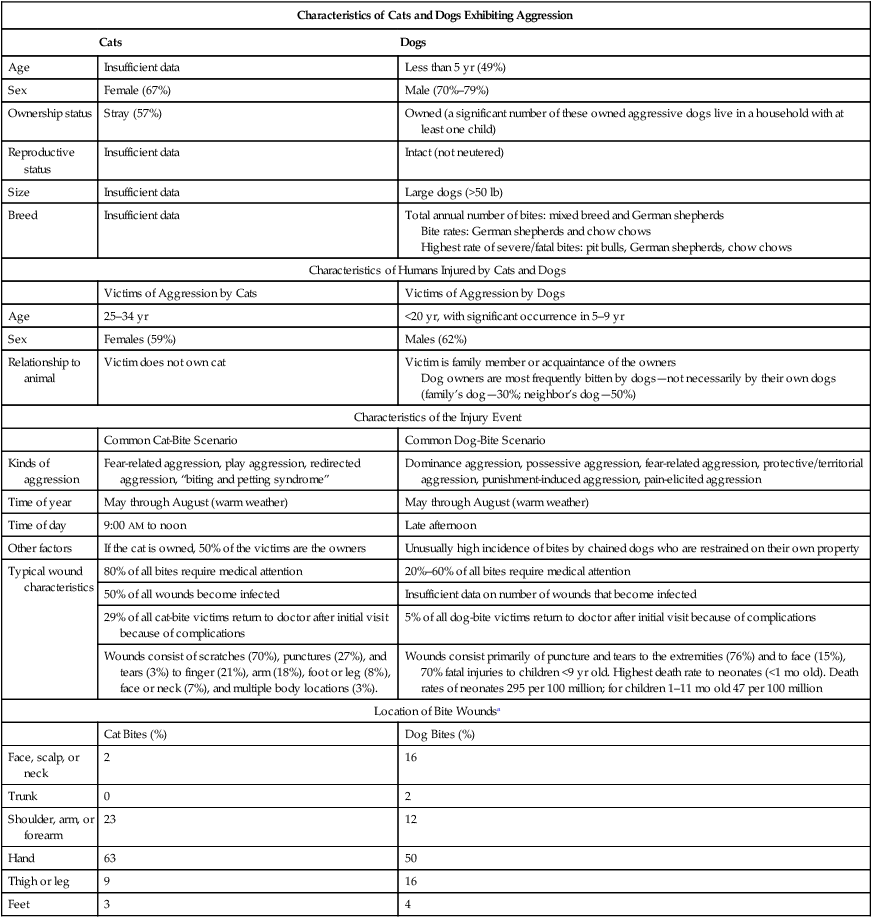

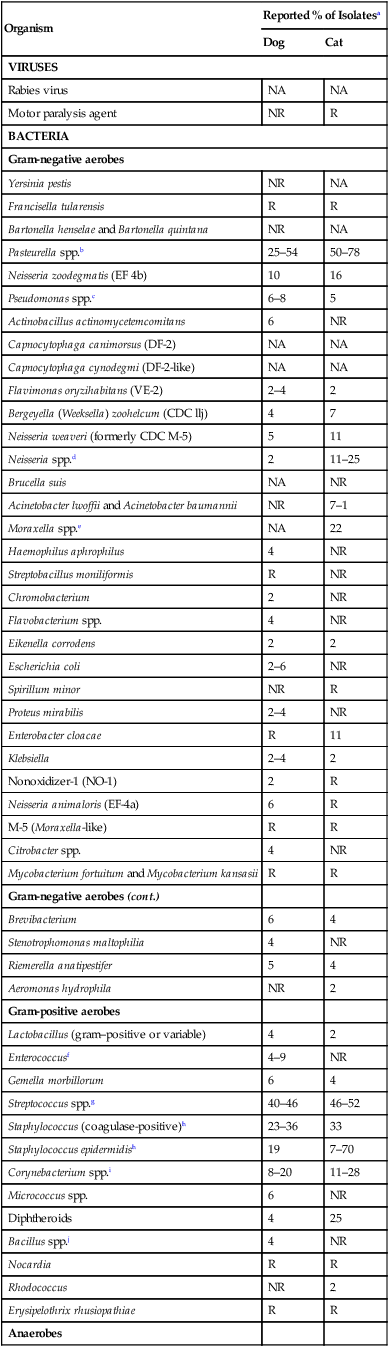

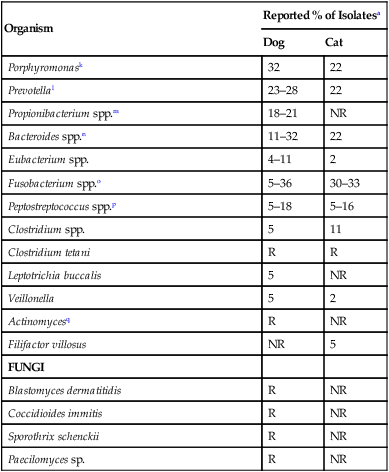

Animal bite wounds are fourth among the most commonly reported human illnesses each year in the United States. Although it is reported that 4.7 million people are bitten by animals in the United States annually,10,47,181,199 fewer than half of the bites are ever reported and only 18% of the people seek medical attention.172 Bites from animals that are pets are even more drastically underreported. More than 90% of animal bites of people are from dogs and cats.143,175,175 Approximately 1% (with a range of 0.2% to 1.1%) of emergency hospital visits by people involve bite injuries.212,237 Data from other reports suggest that similar statistics are found in Europe.* Seventy-two hours after a natural disaster in a geographic area, the incidence of humans receiving dog and cat bites increases because of displaced pets interacting with rescue workers, strangers, and especially those familiar with the pet.234 Results of studies suggest that the incidence of dog bites can be controlled by legislation or practices which restrict the numbers of free-roaming dogs.50a,228a Veterinarians and animal health personnel are at greater risk for injury by dogs and cats than the general population.127 Results of a survey of a group of veterinarians in the United States indicated that approximately 65% had sustained a major animal-related injury.127 Animal bites and scratches accounted for 34% and 3.8%, respectively, of the traumas. Dogs were involved in 24% and cats in 10% of the injuries. In their careers, 92% of the veterinarians surveyed had sustained dog bites, 81% cat bites, and 72% cat scratches. The following epidemiologic discussion focuses on bite injuries that are not related to veterinary practice and for which a veterinarian may be consulted to determine the disposition of the dog or cat responsible for the bite. (However, the information can be applied to injuries that occur within a veterinary practice setting.) The procedures for injured people can also be applied to treating wounds of dogs and cats that are bitten during a fight. The characteristics of dog- and cat-related injuries are summarized in Table 51-1. TABLE 51-1 Epidemiologic Characteristics Associated with Dog- and Cat-Related Bites or Scratches In 2008, one third of American households owned dogs, with a total canine population of 78 million.112 Dog prevalence varies worldwide, and developing countries have a greater percentage of feral domestic dogs. Risk factors for dog bites include the dog’s age, breed, size, medical health, sex, and reproductive status.* Bites are more likely to be delivered by reproductively intact male, large-size (greater than 22.7 kg [50 lb]), 6-month-old to 4-year-old dogs that are mixed breeds, German shepherds, or chow chows. However, breed-specific statements can be inaccurate because of breed popularity and misidentification, inaccurate estimates of a breed’s prevalence, and differences in aggressive behavior. Of the 800,000 annual dog bites in the United States that require medical attention, approximately 20 are fatal.8,68,128,200,237 Approximately 350,000 emergency room visits related to dog bites occur each year10,237; the number of admissions is second only to baseball and softball injuries as admissions for recreational injuries. Reports citing large dogs as the most frequent biters may underestimate the number of bites from smaller dogs.244 However, serious bites to children are commonly inflicted by large dogs.29,83,83 Regardless of size, estimates are that dogs can exert a jaw force of 450 psi, enough to do extensive damage to tissues. Additional pulling and tearing can cause shearing injuries. Dogs cited for causing a high percentage of the severe or fatal bites have included pit bulls, Rottweilers, German shepherds, chow chows, cocker spaniels, and huskies.155,200,200 However, a study in one Florida county found that golden retrievers and cocker spaniels have bitten more people than German shepherds. Unfortunately, many of these studies on breed prevalence for biting are not adjusted for the relative numbers of breed types in the studied dog population. For this and other reasons, specific legislation that restricts ownership of certain breeds has been questioned.46a,171a,174a In one observation, Labrador retrievers and golden retrievers commonly bit their owners or someone petting them, whereas German shepherds, Bernese mountain dogs, and collies tended to be aggressive toward strangers.145 Dominance aggression has been linked to unprovoked attacks on people by dogs. In one behavior clinic, the most prevalent breeds for which dominance aggression was treated were the English springer spaniel, cocker spaniel, Labrador retriever, golden retriever, Dalmatian, Rottweiler, and German shepherd.172 In addition to breed behavior, another important contributory factor to biting is the degree of responsibility exercised by the animal’s owner. Dogs that are less restricted or supervised in their interactions with people are more likely to bite people.146,170 Certain canine behavioral aggressions related to food, fear, pain, territory, possession, or dominance can increase the risk of bite incidents. A survey of fatal dog-bite attacks in the United States from 1979 to 1998 listed the pit-bull-type, Rottweiler, German shepherd, husky-type, malamute, Doberman pinscher, chow chow, great Dane, and Saint Bernard as the most prevalent breeds.201 These data were acquired by searching news accounts and the Humane Society of the United States registry databank. Dog-bite statistics from media reports in North America show that up to 77% of 931 dog attack fatalities and maimings resulted from dogs that were pit-bull types, Rottweilers, wolf hybrids, or a mix of these breeds.44 These data, which may be biased by media interest, show that pit-bull types are the only breed that attacks adults as frequently as children; these dogs may lack normal canine inhibition. In contrast, Rottweilers and other breeds attack children three times more often than they attack adults, indicating that the children’s size may play a role. Wolf hybrids predominantly attack young children (younger than 7 years), suggesting that predation rather than territoriality or reactivity is the reason for their attacks.44 Where two or more dogs are involved in an attack, the fatality rate increases. In Canada, dog-bite fatalities, surveyed from media sources, were similarly from owned, known dogs in residential locations with children having unsupervised access to dogs.184 However, differences from the United States data were those fatal incidents from dog packs in rural locations and higher prevalence of mixed-breed and sled dogs. Furthermore, pit-bull type dogs were underrepresented; however, in Canada they are heavily legislated. Legislation on breed-specific prohibitions in the United States is unlikely to be legally enforceable.232 Some are concerned that data from news services may sensationalize and bias reported incidents.172 Furthermore, the data on fatal attacks should not overshadow the medical importance of nonfatal bite injuries, which likely do not have the same breed bias. Last, dog owners can play a significant role in increasing or decreasing aggressive pet behaviors by the socialization of their dogs and the way they handle aggressive behaviors. No dog is born aggressive, but it can become aggressive through improper discipline and training. Therefore, veterinarians should emphasize and support educating their clients about aggressiveness and legislation directed at controlling undesirable animal behaviors or negligent owners.46a,153,171a,174a,240b Veterinarians should always report aggressive incidents that happen during a pet’s hospitalization to the pet’s owners and others handling the involved pets (Box 51-1). An excellent review of handling aggression in dogs and cats in the veterinary practice has been published.149a Less than 20% of dog bites are provoked; males and children are more likely to be involved in provoked attacks.174 Most dog bites involve a dog owned by the family or a neighbor, and they are often unprovoked. For example, fatal dog bites of newborns often occur when infants are sleeping. Other factors involved with dog bites include the person bitten, the dog-person relationship, and the setting.241 Approximately 75% of bite injuries are in people younger than 21 years, with peak incidence at 5 to 9 years. Children are more likely to provoke dogs and often do not understand the dog’s body language. Reports of the high prevalence of bites among children may be related to the additional attention given to dog bites of children compared with those of adults.51,55,55 Although males make up approximately 65% of all those bitten, boys and girls younger than 6 years account for almost 60% of all fatal bite injuries. More than 50% of injuries among children occur on the head, face, or neck. Any movements in the presence of certain dogs can cause the dogs to become aggressive, especially when children are involved.141,189 Bending over, reaching toward, hugging, or grabbing the collar of a dog are typical human behaviors that may increase the risk of being bitten, especially if a dog is afraid, possessive, or dominant. Other kinds of dog aggression and their eliciting behaviors are discussed elsewhere.245,247 In general, humans are more likely to be bitten by a dog if they own a dog, they are in the presence of a dog owned by someone else, or the dog lives in a household with at least one child.83,141,141 Many dogs bite children after an interaction in the absence of adult supervision.157 Recipients of reported bites are more likely to be neighbors of families who own dogs, with the next likely recipients being the owners, although bites to owners are probably underreported.29,247 Other factors that can affect a dog’s likelihood of biting include whether the dog is chained for long periods,83 geographic location, time of year, time of day, and weather. A majority of dog bite injuries occur between April and September, when warm weather is conducive to outdoor activity (see Table 51-1).244 Biting incidents have also correlated with increasing fullness of the moon.238 A booklet on bite prevention is available at www.statefarm.com/consumer/dogbite.htm or www.avma.org. Additional information on dog bite prevention can be found at www.hsus.org. Information concerning variations in dog bite statutes in the United States has been reviewed.97 An excellent review on the community approach to dog bite prevention was published in a report by an American Veterinary Medical Association task force.9 In a study of dog bites involving caregivers in a veterinary teaching hospital, caregivers interacting with older dogs were more likely to be bitten than those interacting with younger ones.59 Dogs with a propensity to bite already had warning signs posted on their cages. Compared with dog bites, much less has been reported about feline aggression (biting and scratching) toward people.40 Approximately 400,000 cat bites are reported each year in the United States, and cat-induced wounds have a greater propensity for becoming infected than dog-induced wounds. In 2008, one third of American households owned cats, with a total feline population of 88.3 million.112 Cat bites constitute 5% to 25% of animal-related injuries in people, whereas other domestic and wild animals account for less than 1% of reported bites. An epidemiologic study from Valencia, Spain, noted an annual average of 6.36 feline aggression incidents per 100,000 population.173 The most commonly reported cat bites and scratches involve unowned female cats that have injured adult women (see Table 51-1). Scratches and bites are more common in warm weather (the summer season) and the late afternoon. Cat-induced wounds have generally been described as being scratches or punctures.243 The majority of cat bites are provoked by handling cats. Owned cats have bitten people on the neck, face, and multiple sites, whereas strays are more likely to injure the hand. Older humans are more likely to be bitten on the hand. Of the injuries for which medical attention is sought, it is estimated that between 4% and 20% of dog-bite wounds and 20% to 50% of cat-bite wounds become clinically infected.216 Clinical infections usually occur within 8 to 24 hours after injury. Dog-bite injuries may result in significantly more functional impairments, although cat-bite wounds have a greater risk of developing a progressive infection.132 The small incisors of cats cause deep punctures that can penetrate underlying bones, connective and muscle tissues, and joints. Most bite infections are minor; however, at least 10% require suturing, and between 1% and 5% result in hospitalization.235 The infecting organism in bite or scratch injuries usually corresponds to the normal oral microflora of dogs and cats (Table 51-2; compare with Table 88-1), although commensal organisms from the environment or skin around the injury of the victim may also contaminate the wound. Bite wounds are usually polymicrobial, with a median of five isolates per wound comprising three aerobes and two anaerobes.58,216,216 Although more than 80% of cultures produce pathogens, only 15% to 20% of bite wounds become clinically infected.89 The risk of infection is highest (approximately 40%) for crush injuries, puncture wounds, wounds in areas of preexisting edema, and hand wounds.88 Despite the numerous aerobic and anaerobic organisms that contaminate bite wounds, only a few such as Pasteurella multocida, Neisseria animaloris (formerly designated as Eugonic fermenter-4a), and Capnocytophaga canimorsus consistently cause systemic manifestations. In the past the role of strictly anaerobic bacteria in bite wounds has been overshadowed by such notorious genera as Pasteurella. However, with modern methods of anaerobic cultivation, the role of these bacteria in bite wounds has been realized. When present, anaerobic bacteria are usually isolated in mixed cultures. Fusobacterium spp., Bacteroides species, Porphyromonas species, Prevotella species, and other anaerobic gram-negative bacilli are often involved.4,124 Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae has been isolated from dog and cat bites.1,216 An unusual form of motor neuron disease suspected to be caused by a virus occurred after a cat bite.109 TABLE 51-2 Organisms Isolated from Infected Human Wounds Caused by Dog or Cat Bites or Scratches C, Cat; D, dog; NA, not available and may vary based on geographic location; NR, not reported; R, rare or isolated reports. aPercentages are based on isolates of wounds for which patients sought medical attention and are listed in order of relative frequency of isolation. For breakdown of specific genera, see respective footnotes, in which percentage is listed for individual dog or cat isolates. bP. multocida ssp. multocida C: 52%, D: 14%; P. multocida ssp. septica C: 30%, D: 14%; P. dagmatis C: 4%, D: 5%; P. stomatis C: 4%; P. canis D: 27%; P. multocida ssp. gallicida D: 5%; P. pneumotropica D: 5%; P. stomatis D: 5%. cP. aeruginosa D: 2%; P. vesicularis C: 2%, D: 2%; P. diminuta D: 2%; P. putida C: 2%; P. stutzeri C: 2%. dN. subflava C: 2%, D: 2%; N. cinera-flavescens C: 2%; N. mucosa C: 2%. eM. catarrhalis C: 11%; M. osloensis C: 11%; M. atlantae C: 7%; M. nonliquefaciens C: 4%. fE. faecalis C: 4%, D: 6%; E. avium D: 2%; E. malodoratus D: 2%; E. durans C: 9%. gS. mitis C: 23%–33%, D: 22%–36%; S. sanguis II C: 19%, D: 18%; S. equinus C: 11%, D: 5%; S. pyogenes D: 6%–9%; S. constellatus C: 4%, D: 4%; S. mutans C: 4%–11%, D: 4%–12%; S. agalactiae C: 4%, D: 2%; S. sanguis C: 4%, D: 2%, D:–5%; S. sanguis I C: 4%, D: 2%; S. sanguis II C: 12%, D: 8%; S. intermedius C: 4%, D: 6%; S. dysgalactiae D: 1%. hS. epidermidis C: 7%, D: 23%; S. warneri C: 7%, D: 5%; S. aureus C: 4%, D: 14%; S. cohnii D: 5%; S. pseudintermedius C: 4%, D: 9%; S. coagulase neg D: 5%; S. xylosus D: 4.5%; S. haemolyticus C: 4%; S. hominis C: 4%, D: 1%; S. hyicus C: 4%; S. sciuri/lentus C: 4%; S. simulans C: 4%; S. auricularis D: 1%; S. capitis C: 2%; S. saprophyticus C: 2%. iCorynebacterium Group G C: 5%, D: 6%; C. minutissimum C: 7%, D: 4%; C. aquaticum C: 14%, D: 2%; C. jeikeium C: 2%, D: 1%; C. afermentans, Group E, and C. pseudodiphtheriticum, all D: 2%; Group B, Group F-1, C. kutscheri, C. propinquum, and C. striatum, all C: 2%. jB. firmus C: 4%, D: 4%; B. circulans C: 2%, D: 2%; B. subtilis D: 2%. kP. macacae C: 7%, D: 6%; P. gingivalis C: 7%, D: 9%; P. cangingivalis C: 4%, D: 5%; P. canoris C: 9%, D: 4%; P. salivosa C: 4%, D: 4%; P. circumdentaria C: 5%, D: 2%; Porphyromonas spp. D: 5%; P. cansulci C: rare, D: 6%; P. levii–like D: 2%; P. cangingivalis C: 4%, D: 4%. lP. bivia C: 11%; P. heparinolytica C: 9%, D: 14%; P. intermedia/nigrescens D: 5%; P. melaninogenica C: 2%, D: 5%; Prevotella spp. C: 8%; P. zoogleoformans C: 2%, D: 4%; P. denticola D: 2%. mP. acnes C: 16%, D: 14%; P. acidi/propionicus D: 2%; P. avidum C: 2%; P. lymphophilium C: 2%. nB. tectum C: 28%, D: 14%; B. forsythus D: 4%; B. ureolyticus D: 9%; B. gracilis D: 5%; B. fragilis C: 2%, D: 5%; B. ovatus D: 2%. oF. nucleatum C: 26%, D: 18%; F. russii C: 15%, D: 5%; F. gonidiaformans C: 4%, D: 5%; F. alocis D: 2%. pPeptostreptococcus spp. C: 5%, D: 8%; P. asaccharolyticus D: 2%. qA. viscosus C: 2%, D: 4%; A. neuii ssp. anitratus D: 2%. The public health aspects of rabies, tetanus, and bartonellosis are discussed in Chapters 20, 41, and 52, respectively. Humans who have been bitten may have to be hospitalized if they develop significant local or systemic infections; are unresponsive to oral antibacterials; have penetrating wounds of tendons, joints, or the central nervous system; have open fractures; have significant blood loss or airway injuries; require reconstructive surgeries; require wound elevation; have head or hand injuries; or are immunocompromised.235 Bite wounds caused by dogs and cats may contain some unique bacteria that have not been previously identified in people. Although some, such as Pasteurella organisms, are commonly found in animal bite wounds, others such as Riemerella anatipestifer in the cat mouth and Bacteroides tectum, which is found in cat and dog bites, are unique to these animals. Eikenella corrodens, a pathogen often found in wounds caused by human bites, has been reported once each as a result of a dog bite and a cat bite.216 Corynebacterium canis, a newly characterized species, has been isolated from a dog bite infection.74a Unfortunately, some of the unusual bacterial isolates described previously may not be responsive to conventionally used antibacterials. These organisms are small, nonmotile, gram-negative, bipolar-staining bacilli that are clinically significant in many dog- and cat-bite wounds.72 These organisms normally inhabit the nasal, gingival, and tonsillar regions of approximately 12% to 92% of dogs and 52% to 99% of cats, as well as many other animals. Pasteurella species have been reclassified based on their DNA homology. P. multocida ssp. multocida and ssp. septica have been the most common isolates from clinically healthy cats, whereas Pasteurella canis has not been frequently isolated from healthy dogs.23,150 Pasteurella dagmatis has been uncommonly isolated from the oral cavity of dogs and cats, and some feline P. dagmatis-like isolates have been reclassified as a new genomospeies.206a This same distribution is found with bite-associated infections in humans. Strains isolated from wounds caused by cats were more commonly pathogenic (71%) than those from dogs (8%). P. multocida ssp. multocida (P. multocida) and ssp. septica (P. septica) have been isolated in more serious or systemic infections caused by biting or licking of wounds by dogs or cats.106,167 The frequency of isolation determined by one of the authors (EJG) is as follows: in cat bite wounds, P. multocida is 50% and P. septica is 30%; in dog bite wounds, Pasteurella canis is 27%, P. multocida is 13%, and P. septica is 13% (see Table 51-2).90 Isolation of P. dagmatis is rare.52,96 P. canis was the cause of bacteremia in a patient with alcoholic cirrhosis whose dog licked his leg wound.2a Although many cats and dogs harbor Pasteurella organisms in their saliva, the risk of infection in people is low if they have not been bitten.195 Although dog bites account for more than 80% of emergency room visits related to animal bites, cats are responsible for approximately 75% of bites or scratches contaminated with Pasteurella. More than 50% of all cat-bite wounds and 20% to 30% of all dog-bite wounds are contaminated with Pasteurella.132 Pasteurella infections also have been reported after bite injuries caused by large exotic Felidae.42 Scratch injuries from dogs are less likely to cause Pasteurella infections than cat scratches, unless the scratch is also associated with a bite injury.142 Cats frequently lick their paws and usually hiss when they scratch, thereby producing aerosolized secretions that contaminate the wounds, which is probably related to the higher prevalence of Pasteurella-infected scratches. A person who was licked daily on her hands by her dog developed a Pasteurella throat abscess after tonsillectomy.106 Pasteurella meningitis developed in a person with extensive dental caries who regularly kissed the family dog. Pasteurella has been isolated from the oral cavities of some people who have kissed their dogs and cats but not from those who have not.11,12 Pasteurella acquired from pets may also cause various upper respiratory tract infections, including tonsillitis,252 sinusitis,13,160 and epiglottiditis.198 Submandibular cellulitis (Ludwig’s angina) developed in a previously healthy person 10 days after playing with a dog.60 Pasteurella peritonitis has developed in dialysis patients after a cat scratch or bite in the tubing of the home dialysis machines.134,195a,202a Nontraumatic domestic cat exposure has also been associated with Pasteurella peritonitis in people with hepatic cirrhosis.122 Joint arthroplasties have become infected with P. multocida when people have been bitten scratched or licked by cats or dogs.27,76,100a Although a majority of human P. multocida infections are related to animal bites, people also may develop pasteurellosis from general animal exposure. In most of these cases, licking of the human’s intact or injured skin by the pet and inhalation or ingestion of animal secretions are the most likely sources of entry. Infections associated with inhaled or disseminated microorganisms frequently localize in the gastrointestinal or respiratory tracts or the central nervous system. Patients who are immunosuppressed or have a predisposing underlying illness such as diabetes mellitus and hepatic dysfunction are more likely to develop bacteremia and die. Meningitis has been reported in infants and children who have been licked in the face by family dogs.221 Even neonatal puppies may be susceptible to certain virulent strains of Pasteurella, presumably acquired from the oral cavity of their dam. A virulent strain of P. canis biotype 1 was determined to be the cause of mortality in neonatal puppies with multisystemic infection.56 For further information on the zoonotic risk of these organisms, see Pasteurellosis Chapter 99. This gram-negative bacillus, previously classified as Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) IIj, is a component of the normal oral flora of dogs, cats, and other animals. Few instances have been reported of infection in people caused by a bite wound from dogs or cats.152,216 Abscesses, tenosynovitis, meningitis, and pneumonia have occurred. The organism is susceptible to β-lactam antibacterials, quinolones, and chloramphenicol. N. animaloris and Neisseria zoodegmatis (previously Eugonic Fermenter-4 a and b, respectively) are resident oropharyngeal and nasal microflora of dogs and cats. Isolation rates vary, with 30% to 90% of clinically healthy animals having these bacteria.79 These Neisseria species are more prevalent than Pasteurella in the oropharynx of dogs. They can cause severe illness in immunocompromised people or when inoculated into deep bite puncture wounds. They have been divided by biochemical features into two biovars, N. animaloris and N. zoodegmatis, which have different pathogenic potentials.6 N. animaloris has been isolated from infected dog bite wounds in people and has been associated with deeper or systemic infections in people. In contrast, N. zoodegmatis has been found in wounds caused by bites from dogs and cats.216 N. zoodegmatis has also been the predominant isolate associated with virulent pneumonia in dogs and cats (see Bacterial Respiratory Infections, Chapter 87). Neisseria weaveri and P. multocida were isolated from a child that was bitten by a tiger.39 Capnocytophaga species are capnophilic (carbon dioxide–flourishing), gram-negative, gliding bacteria that are closely related to Fusobacterium and Bacteroides species. They are commonly isolated from the oral cavities of people and animals. The organisms are divided into two main groups: (1) species from the human oral cavity (Capnocytophaga ochracea, Capnocytophaga gingivalis, Capnocytophaga haemolytica, Capnocytophaga granulosa and Capnocytophaga sputigena—previously CDC biogroup dysgonic fermenter-1 [DF-1]) and (2) species found in the oral cavities of dogs, cats, and other animals (Capnocytophaga canimorsus (Latin canis = “dog,” morsus = “bite”) and Capnocytophaga cynodegmi—previously CDC biogroup DF-2). In immunocompetent humans, Capnocytophaga can produce various infections including in the respiratory tract, wounds, bone, and abdomen. In immunocompromised peoples, fatal bacterial sepsis and endocarditis can result.43b,96a,100,212a,233 C. canimorsus is a slow-growing (3 to 11 days in culture), thin, filamentous, non-spore-forming, nonmotile, pleomorphic, facultative aerobic, gram-negative bacillus. It has been associated with fatal septicemia in humans, predominantly after dog bites and less commonly after cat bites or scratches.138,226 It has been isolated from the oral cavities of 16% and 18% of clinically healthy dogs and cats, respectively.235 Many human infections have been reported in the literature with a mortality rate approaching 30%. Although multiple occurrences may be likely, there are only two reports of infection in a nonhuman species subsequent to dog bites.147,228 C. canimorsus has an unusual propensity to cause systemic bacteremia, presumably because of its tropism for endothelial surfaces and its inherent resistance to serum complement. It also resists phagocytosis by macrophages and blocks the bactericidal ability of macrophages.82,147 The organism is able to avoid the human immune system as it does not interact with human Toll-like receptor 4 because of the unique lipid A fraction of its lipopolysaccharide. It is resistant to phagocytosis and killing by macrophages. The majority of C. canimorsus infections have occurred in immunocompromised individuals older than 40 years. A veterinarian who had undergone a splenectomy died from an illness after a dog bite. Most people who develop fatal complications of C. canimorsus infection have underlying contributing factors, such as cytotoxic chemotherapy–induced or surgical splenectomy, glucocorticoid therapy, Hodgkin’s disease, macroglobulinemia, alcoholism, peptic ulcer, arteriosclerotic heart disease, hemoglobinopathy, immune-mediated thrombocytopenia, granulomatous or other chronic lung disease, chronic arthritis, neutropenia, intestinal malabsorption, or old age (older than 65 years). Presumably, the factors caused defects in the phagocytic immune defenses, and the individuals could not eliminate the organism from the blood. As with pasteurellosis, some patients with C. canimorsus sepsis have been exposed to dogs, cats, or other carnivores or to outdoor environments but had no known bites. C. canimorsus infections have also been reported in animals including a dog-bite wound inflicted on a rabbit228 and dog.147 C. canimorsus was isolated from the nasal passages of a cat with chronic sinusitis and rhinitis.74 Ocular keratitis and blepharitis have developed in people who were closely associated with their pet dogs or cats but have also developed in other people with no known animal exposure. Corneal scratch injuries from cats have also produced keratitis in people. Results from DNA hybridization and biochemical studies have shown that the more virulent species isolated from people with septicemia were C. canimorsus, and those from localized (noninvasive) wound infections or keratitis were C. cynodegmi (DF-2–like). Outside of the oral cavities of animals, C. cynodegmi has been isolated from the lower respiratory tract of a cat with bronchoalveolar carcinoma69 and Capnocytophaga sp. from the nasal passage of a cat with chronic sinusitis74; however, these isolations may represent oropharyngeal contamination and not disease involvement. Other Capnocytophaga species are part of the normal gingival flora of people and cause problems such as conjunctivitis, periodontitis, gingivitis, abscesses, and body cavity infections.64,71 In addition, they can cause bacteremia in immunocompromised individuals.91 Infections with these other Capnocytophaga are not associated with animal exposure. For further information on the zoonotic risk of these organisms for humans, see Capnocytophagiosis, Chapter 99. The nonoxidizer-1 (NO-1) group of bacteria, CDC NO-1, comprises isolates of an unusual bacterium that has been only recovered from people bitten by dogs (77%), cats (18%), and other animals (5%).117 The bites were on various parts of the body. Isolates have been described as fastidious, gram-negative pleomorphic rods. The organisms are similar to asaccharolytic strains of Acinetobacter. Numerous other bacteria can be isolated from infected wounds; however, isolation of these bacteria appears to be unique to animal bites. Dogs and cats should be considered reservoirs for these bacteria. This organism, which had previously been isolated only from dogs, was isolated from the bite wound of a previously clinically healthy person.35 A newly described member of the genus, C. freiburgense sp. nov., was isolated from a dog-bite wound.75

Bite Wound Infections

Dog and Cat Bite Infections

Epidemiology of People Bitten by Animals

Characteristics of Cats and Dogs Exhibiting Aggression

Cats

Dogs

Age

Insufficient data

Less than 5 yr (49%)

Sex

Female (67%)

Male (70%–79%)

Ownership status

Stray (57%)

Owned (a significant number of these owned aggressive dogs live in a household with at least one child)

Reproductive status

Insufficient data

Intact (not neutered)

Size

Insufficient data

Large dogs (>50 lb)

Breed

Insufficient data

Total annual number of bites: mixed breed and German shepherds

Bite rates: German shepherds and chow chows

Highest rate of severe/fatal bites: pit bulls, German shepherds, chow chows

Characteristics of Humans Injured by Cats and Dogs

Victims of Aggression by Cats

Victims of Aggression by Dogs

Age

25–34 yr

<20 yr, with significant occurrence in 5–9 yr

Sex

Females (59%)

Males (62%)

Relationship to animal

Victim does not own cat

Victim is family member or acquaintance of the owners

Dog owners are most frequently bitten by dogs—not necessarily by their own dogs (family’s dog—30%; neighbor’s dog—50%)

Characteristics of the Injury Event

Common Cat-Bite Scenario

Common Dog-Bite Scenario

Kinds of aggression

Fear-related aggression, play aggression, redirected aggression, “biting and petting syndrome”

Dominance aggression, possessive aggression, fear-related aggression, protective/territorial aggression, punishment-induced aggression, pain-elicited aggression

Time of year

May through August (warm weather)

May through August (warm weather)

Time of day

9:00 AM to noon

Late afternoon

Other factors

If the cat is owned, 50% of the victims are the owners

Unusually high incidence of bites by chained dogs who are restrained on their own property

Typical wound characteristics

80% of all bites require medical attention

20%–60% of all bites require medical attention

50% of all wounds become infected

Insufficient data on number of wounds that become infected

29% of all cat-bite victims return to doctor after initial visit because of complications

5% of all dog-bite victims return to doctor after initial visit because of complications

Wounds consist of scratches (70%), punctures (27%), and tears (3%) to finger (21%), arm (18%), foot or leg (8%), face or neck (7%), and multiple body locations (3%).

Wounds consist primarily of puncture and tears to the extremities (76%) and to face (15%), 70% fatal injuries to children <9 yr old. Highest death rate to neonates (<1 mo old). Death rates of neonates 295 per 100 million; for children 1–11 mo old 47 per 100 million

Location of Bite Woundsa

Cat Bites (%)

Dog Bites (%)

Face, scalp, or neck

2

16

Trunk

0

2

Shoulder, arm, or forearm

23

12

Hand

63

50

Thigh or leg

9

16

Feet

3

4

Dog Bites

Cat Bites

Bite Wounds

Organism

Reported % of Isolatesa

Dog

Cat

VIRUSES

Rabies virus

NA

NA

Motor paralysis agent

NR

R

BACTERIA

Gram-negative aerobes

Yersinia pestis

NR

NA

Francisella tularensis

R

R

Bartonella henselae and Bartonella quintana

NR

NA

Pasteurella spp.b

25–54

50–78

Neisseria zoodegmatis (EF 4b)

10

16

Pseudomonas spp.c

6–8

5

Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans

6

NR

Capnocytophaga canimorsus (DF-2)

NA

NA

Capnocytophaga cynodegmi (DF-2-like)

NA

NA

Flavimonas oryzihabitans (VE-2)

2–4

2

Bergeyella (Weeksella) zoohelcum (CDC llj)

4

7

Neisseria weaveri (formerly CDC M-5)

5

11

Neisseria spp.d

2

11–25

Brucella suis

NA

NR

Acinetobacter lwoffii and Acinetobacter baumannii

NR

7–1

Moraxella spp.e

NA

22

Haemophilus aphrophilus

4

NR

Streptobacillus moniliformis

R

NR

Chromobacterium

2

NR

Flavobacterium spp.

4

NR

Eikenella corrodens

2

2

Escherichia coli

2–6

NR

Spirillum minor

NR

R

Proteus mirabilis

2–4

NR

Enterobacter cloacae

R

11

Klebsiella

2–4

2

Nonoxidizer-1 (NO-1)

2

R

Neisseria animaloris (EF-4a)

6

R

M-5 (Moraxella-like)

R

R

Citrobacter spp.

4

NR

Mycobacterium fortuitum and Mycobacterium kansasii

R

R

Gram-negative aerobes (cont.)

Brevibacterium

6

4

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia

4

NR

Riemerella anatipestifer

5

4

Aeromonas hydrophila

NR

2

Gram-positive aerobes

Lactobacillus (gram–positive or variable)

4

2

Enterococcusf

4–9

NR

Gemella morbillorum

6

4

Streptococcus spp.g

40–46

46–52

Staphylococcus (coagulase-positive)h

23–36

33

Staphylococcus epidermidish

19

7–70

Corynebacterium spp.i

8–20

11–28

Micrococcus spp.

6

NR

Diphtheroids

4

25

Bacillus spp.j

4

NR

Nocardia

R

R

Rhodococcus

NR

2

Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae

R

R

Anaerobes

Porphyromonask

32

22

Prevotellal

23–28

22

Propionibacterium spp.m

18–21

NR

Bacteroides spp.n

11–32

22

Eubacterium spp.

4–11

2

Fusobacterium spp.o

5–36

30–33

Peptostreptococcus spp.p

5–18

5–16

Clostridium spp.

5

11

Clostridium tetani

R

R

Leptotrichia buccalis

5

NR

Veillonella

5

2

Actinomycesq

R

NR

Filifactor villosus

NR

5

FUNGI

Blastomyces dermatitidis

R

NR

Coccidioides immitis

R

NR

Sporothrix schenckii

R

NR

Paecilomyces sp.

R

NR

Bacteria Relatively Unique to Dog and Cat Bites

Pasteurella

Bergeyella (Weeksella) zoohelcum

Neisseria

Capnocytophaga

Nonoxidizer-1

Corynebacterium auriscanis

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Bite Wound Infections