CHAPTER 30 Anatomy of the Ear in Health and Disease

EAR PINNA

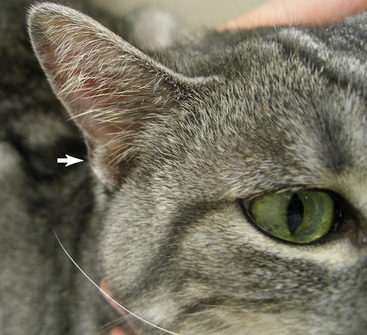

The pinna is triangular in appearance with the tip of the triangle distal (Figure 30-1). There is a concave surface that faces rostrolaterally and a convex surface that faces caudomedially. This shape is valuable in collecting sound and directing it toward the ear canal and eventually the tympanic membrane.

PRIMARY LESIONS THAT MAY BE SEEN ON THE PINNA

Pustule

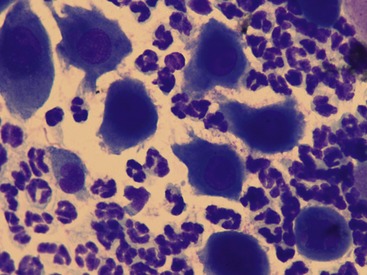

A pustule is a circumscribed, elevated lesion that contains polymorphonuclear cells (neutrophils, eosinophils). It may be caused by infections (bacterial or fungal infection [e.g., dermatophyte]) or may be sterile such as in pemphigus foliaceus. Pemphigus foliaceus (PF) is the most common cause of pustules on the pinna of cats and cytological examination of these pustules often reveals acanthocytes compatible with PF (Figure 30-2). In fact, if pustules are seen on the pinna of a cat, the author considers PF to be the working diagnosis until histopathological examination proves otherwise. (See Chapter 29 in the fifth volume of this series for a complete discussion of pemphigus foliaceus.)

SECONDARY LESIONS THAT MAY BE SEEN ON THE PINNA

Scale

Scale is an accumulation of fragmented (desquamated) corneocytes from the stratum corneum. Scales per se are not abnormal; in fact, human beings shed approximately one billion cells each day.1 Normally, scale fragments are so small that they are not visible to the naked eye. Abnormal scaling is an accumulation of these fragments so that they are visible without magnification. Any process that affects the degradation of the intercellular lipids or corneodesmosomes, or increases the proliferation of the basal keratinocytes, will create scale. Inflammation is a common cause of scale. Inflammatory cytokines that are produced when the epidermis is damaged include tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) and interleukin-6 (IL-6). Damaged epidermis also stimulates the production of lipid mediators. These inflammatory lipid mediators are produced by the metabolism of phospholipids in keratinocyte cell membranes into free arachidonic acid that is further metabolized into inflammatory eicosanoids, such as prostaglandins, thromboxanes, and leukotrienes. These cytokines and inflammatory eicosanoids stimulate epidermal proliferation in an effort to remove the noxious insult. However, this epidermal hyperproliferation also leads to defective differentiation of the keratinocytes. Inflammation that occurs with allergic skin disease (atopy, cutaneous adverse food reaction), cheyletiellosis, Otodectes infestation, or dermatophytosis is a common cause of pinnal scaling. Pemphigus foliaceus, vasculitis, cutaneous T cell lymphoma, and cutaneous drug reaction (allergic or irritant) also may be accompanied by scaling.

Crusts

Crusts are the result of dry plasma or exudate on the skin. Cats frequently will have a lesion that is a combination of a papule and a crust known as a papulocrust. When crusts or papulocrusts are identified, dermatophytosis, autoimmune disease (PF, vasculitis, drug reaction), environmental allergen–induced atopic dermatitis, cutaneous adverse food reaction, flea allergy dermatitis, a bacterial skin infection (caused by an underlying hypersensitivity), Notoedres cati infestation, Trombicula (usually Neotrombicula automnalis) infestation, or a louse infestation (Felicola subrostrata) should be considered as possible causes (Figure 30-3).

On the caudal lateral surface of the proximal pinna is a small pouch, the cutaneous marginal pouch (see Figure 30-1). The purpose of this pouch is unknown; however, it is an easily accessible area for collecting skin biopsies of the pinna when needed (e.g., confirming PF, cutaneous small vessel vasculitis).

EAR CANALS

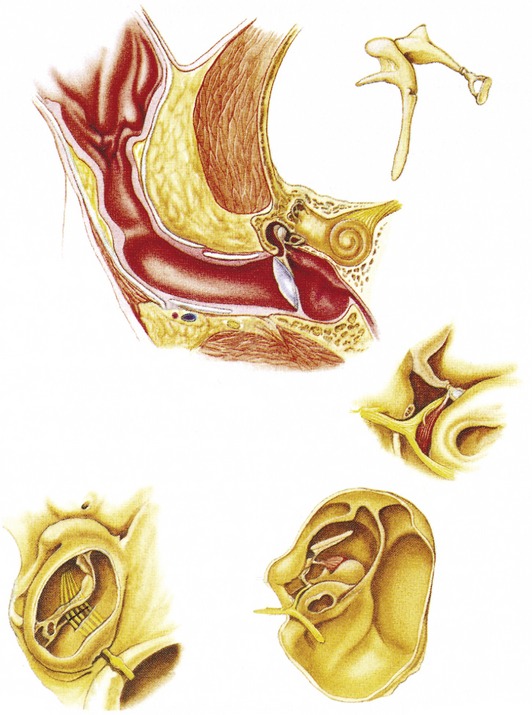

The next step is an otoscopic examination, which involves examining the ear canals and tympanic membrane (Figure 30-4). To evaluate the ear canals and the tympanic membrane, the tip of the otoscope cone should be placed in the opening of the external vertical ear canal. In order to perform a proper otoscopic examination, it is important to understand the path that the vertical ear canal travels. Because the vertical canal travels ventrally and slightly rostrally, the otoscope cone initially should be directed vertically rather than horizontally, while gently pulling up on the pinna. There is a curve in the canal at the point where the vertical ear canal changes into the horizontal ear canal. This area is identified by a ridge of cartilage on the dorsal surface of the canal. This landmark is important to identify, because to gain entrance to the horizontal ear canal and visualize the tympanic membrane, the otoscope cone must be passed gently under this ridge. This is best accomplished by gently pulling on the pinna dorsally and laterally as the otoscope cone is advancing proximally in the ear canal.

The most medial border of the horizontal ear canal ends at the tympanic membrane. As the auricular cartilage approaches the tympanic membrane, the annular cartilage replaces it. The annular cartilage ends just lateral to the tympanic membrane, and the osseous external auditory meatus begins. This bony part of the external ear canal, which is an extension of the temporal bone, forms the most proximal part of the horizontal ear canal and terminates lateral to the tympanic membrane (see Figure 30-4). The temporal bones originate from the ventrolateral wall of the skull. Within the temporal bones are the sensory organs for hearing and balance (middle and inner ear). They also surround the proximal end of the external ear canal. This enclosure protects these important structures.

In contrast to our stereotypical skin, there are very few hairs in the ear canal of cats (unlike dogs, who may have copious amounts depending on breed). The external ear canal is lined by skin that, like skin on other parts of the body, contains hair follicles, and sebaceous and apocrine sweat glands. The sebaceous glands tend to secrete an oily substance, whereas the ceruminous glands (modified apocrine glands) secrete a milky white fluid that changes to a brown color when exposed to air. The combined product of these sweat glands is called cerumen. In human beings cerumen contains saturated and unsaturated long-chain fatty acids, cholesterol, cholesterol esters, wax esters, squalene, and triglycerides.2

There are different consistencies to the cerumen in human beings and dogs, varying from a very dry flaky appearance to the more typical moist form.2 The type of cerumen that is present in human beings is a reflection of the macroenvironment, especially the humidity, and also genetics. The author has not appreciated any pattern to the form that is present in dogs. Cats do not appear to have both forms, just the moist form.

Even though we focus frequently on cleaning ears to remove cerumen, it is important to understand that cerumen performs some very important functions. As mentioned previously, the purpose of cerumen is to protect the ear canals and the tympanic membrane by trapping and then mechanically removing resident bacteria and yeast and toxins produced by these organisms.3 Cerumen also removes foreign material that may have entered the ear canal. The lipids and free fatty acids that are present in cerumen contribute to the barrier function of the epidermis of the ear canals. They perform this function by keeping the epidermis of the ear canals and the tympanic membrane moist. Also, by maintaining proper moisture, normal desquamation of the epidermis may occur.

Fatty acids present in cerumen are derived from the breakdown of sebaceous gland triglycerides. This hydrolysis occurs as the triglycerides are excreted onto the surface of the ear canal. The lipids that are present in cerumen have potent antibacterial activity. Recently two sebaceous gland–derived fatty acids (sapienic acid, C16:1D6, and lauric acid, C12:0) have been identified that are especially potent antimicrobial molecules.4 The issue of whether cerumen has antimicrobial properties is undecided in human medicine.5 What confuses the issue at this time is that in the presence of infection, cerumen, with its antimicrobial molecules, is produced in excess yet the infection continues.6 This may be explained by studies suggesting that the lipid-rich cerumen is an ideal medium for proliferation of bacteria and fungi.7,8 This apparent disconnect between the presence of excessive cerumen in cases of bacterial otitis externa and the antimicrobial properties of cerumen may be explained by differences in the components of the cerumen. When inflammation occurs in the ear canal, with or without a concurrent bacterial or yeast infection, the ceruminous glands will become hyperplastic and secretion from the glands will accumulate in the ear canals. In addition, the amount of sebaceous secretion decreases. Perhaps this difference in cerumen content has an impact on its antibacterial properties. Other investigators report that immunoglobulins, not cerumen, are responsible for protecting the external ear canal.6 More research in this area will have to be performed before an answer is found.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree