CHAPTER 80 Catteries

Reproductive Performance and Problems

REPRODUCTIVE PHYSIOLOGY

SEASONALITY

The female domestic cat is seasonally polyestrous and a long-day breeder. Increased day length induces estrus. The mean duration of the reproductive season varies with geographical latitude. Near the equator, no seasonality is seen, while the seasonal anestrus typically lasts from September to January in the northern hemisphere.1,2 However, large individual variations in the length of the reproductive season cause wide normal ranges within the same geographical latitude.2 Seasonality often is more pronounced in cats allowed outdoors than in cats confined indoors, because artificial light can interfere with the natural photoperiods. Feral cats have a pronounced seasonal pattern, with most pregnancies found in the spring.3 Although seasonality can be observed in the distribution of litters in pedigree catteries, it is less pronounced than in feral cats, probably because of the influence of artificial light on cats confined indoors and perhaps also because of genetic background.4,5 A genetic influence on the sensitivity for alterations in daylight is indicated by breed differences in seasonality. The Persian breed, for example, generally has a more pronounced seasonality than the Burmese breed.4–6

Light programs can be used to control the estrus cycle. A day length less than 8 hours will suppress estrous activity. To induce cyclicity throughout the year, owners should ensure a constant day length of 12 hours or more.1 In a room with windows, the changes in natural photoperiods may interfere with a light program; therefore an environment that allows for full control over the amount of light may be necessary for successful control of the estrous cycle.

Although it is known that male cats can produce offspring throughout the year, the effect of season on reproductive function in the male domestic cat has not been explored sufficiently. Recent studies indicate, however, that sperm quality may decrease during the nonreproductive season.7,8

PUBERTY

Female

The queen will have her first estrus between 4 and 21 months of age, with a median around 9 to 12 months.6,9 Because cyclicity is controlled by the day length, age of puberty will be affected by season. Depending on month of birth, the queen may enter her first estrus during the next breeding season or during the season the second year after birth.2 There seem to be some breed differences in the age of puberty. The Siamese and Burmese breeds reach puberty at an earlier age, on average, than the Persian breed, although individual variations often overlap breed differences.6,9

Male

Spermatogenesis is generally established at 6 to 8 months of age, at which time an increase in testicular weight and testosterone production can be observed, but the spermatogenic function usually is not mature until after 8 to 12 months of age.10 The age when the male starts to mate may, however, vary more than the age of established spermatogenesis. Some individual males in long-haired breeds do not breed until they are 3 years of age.

THE ESTROUS CYCLE

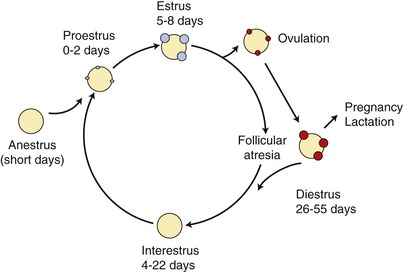

The queen typically is an induced ovulator, which means that a mating stimulus usually is required for ovulation to occur. Spontaneous ovulations, however, also can occur. The phases in the estrous cycle in the nonmated queen can be characterized as the follicular phase (proestrus and estrus) and the nonfollicular phase (interestrus). Estrus is followed by the luteal phase if a sterile mating induces ovulation or if the queen ovulates spontaneously (Figure 80-1).

Follicular Phase

The follicular phase, determined as the period when estradiol levels are above basal level, has a duration of 3 to 16 days and is not affected by mating or ovulation. The onset of the follicular phase is abrupt, with a twofold increase in estradiol-17β, within 24 hours. When estradiol is increased above basal levels, some queens will show estrous behavior the first day; however, the majority do not exhibit behavioral estrus until day 3 or 4 in the follicular phase.11

A short period of proestrus often can be observed. During proestrus, the queen starts to shows estrous behavior but she does not allow mating. Estrus is defined as the period when the queen allows mating. The follicles increase in size and reach a diameter of 2 to 3 mm. The average duration of estrous behavior is 5 to 8 days, with a range of 2 to 19 days.11,12 The duration is not affected by mating or ovulation.12,13 Estrous behavior may continue for 1 to 4 days after the end of the follicular phase.11

Estrous behavior is induced by an increase in estradiol during the follicular phase. Typical behaviors observed during estrus are increased affection, vocalization, restlessness, loss of appetite, increased frequency of urination, rolling, rubbing of the head, and lordosis.14 Lordosis may be shown spontaneously or can be provoked by grasping the female by the scruff of the neck and scratching around the tail. The queen then will lower her chest, elevate her pelvis, tread with her legs, and deviate her tail. When the queen is lifted, the back often will be stiff as she tries to stretch and arch it. A clear vaginal discharge often can be observed.14 Behaviors displayed during estrus also can be seen to some extent when the queen is not in estrus or in neutered females, but their intensity and frequency are more pronounced in estrus. There are, however, individual variations in the intensity of estrous behavior. Intensity also may depend on environment and stress. If the queen is put in an unfamiliar environment, she will often show a less pronounced behavior because of insecurity.

Interestrus

In the absence of a mating stimulus, ovarian follicles regress after estrus.13 During interestrus the queen shows no estrous behavior. The duration of interestrus varies but is usually 4 to 22 days during the reproductive season.11

Diestrus or Pseudopregnancy

Although the queen typically is an induced ovulator, spontaneous ovulations do occur.15 A nonpregnant luteal phase occurs after a sterile mating or a spontaneous ovulation. The diestrus phase also is called pseudopregnancy. Basal level of progesterone is less than 3 nmol/L.13 The first significant increase in progesterone is seen from days 3 to 4 after mating.16,17 Peak levels are reached between days 13 and 21, after which concentrations decrease steadily.13,17 Progesterone concentrations do not differ significantly from those of pregnant animals until around day 30, after which levels are significantly lower in pseudopregnant queens. The duration of diestrus is 26 to 55 days, with a mean of 38 days, giving a cycle length of 6 to 10 weeks in nonpregnant ovulating queens.13 There is no increase in prolactin concentration in the pseudopregnant cat, in contrast to the pregnant queen.18

ENDOCRINOLOGY IN THE MALE CAT AND THE EFFECTS OF TESTOSTERONE

In intact males testosterone is released in a pulsatile fashion without any apparent rhythm and varies between nondetectable and 81.5 nmol/L. Testosterone reaches basal levels (0 to 1.7 nmol/L) within 24 hours after castration.19 The glans penis of the male cat is covered with spines. The development of the penile spines is related directly to testosterone production. The spines start to develop around 2 months of age and are fully developed around 6 to 7 months. The penile spines regress after castration. The presence of penile spines indicates that a male cat produces testosterone.20,21 In young domestic kittens, the prepuce is attached to the penis by loose connective tissue. The penis and the prepuce are separated under the influence of androgens. This attachment may remain if a male cat is castrated at a young age.20,22

MATING AND OVULATION

Management of Mating

Mating causes a reflex that releases gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from the hypothalamus. In response to the GnRH surge, luteinizing hormone (LH) is released from the pituitary gland, which induces ovulation. When a threshold of LH has been reached, mature oocytes ovulate. Often more than one mating is required to reach the threshold of LH. In one study, only 50 per cent of all queens who were mated only once had an LH release that reached the threshold required for ovulation to occur.23

It is necessary to consider the temperament of cats, their mating behavior, and the mechanism of ovulation. Because cats are territorial, it usually is better to bring the female to the male for mating, because the likelihood of a successful mating is increased if the male is in familiar surroundings. If the female is very frightened and nervous, it may be better to move the male to the female. There must be enough space for the male to withdraw from the female’s postcoital reaction. The cats should not be separated before day 3 or 4 of estrus, because some queens will not ovulate after a mating in early estrus.16 Because the release of LH depends on the number of matings, at least four matings should be allowed during the same day. Some cats will not mate when observed, and each mounting may not be followed by a mating. The postcoital reaction is, however, an indication that there has been an intromission.

Breeders sometimes believe that allowing cats to mate for several days during estrus will result in kittens of different ages in the litter; therefore they restrict the number of days for mating. There is, however, no evidence that there will be ovulations on more than one occasion during estrus. Once the threshold of LH has been reached, all mature follicles will ovulate.24 Fertilization can only take place up to approximately 49 hours after ovulation induction (17 to 24 hours after ovulation); therefore all embryos will be of similar age.25

DIAGNOSTIC METHODS TO MONITOR THE ESTROUS CYCLE

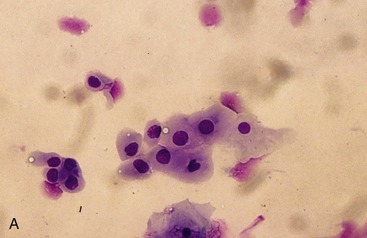

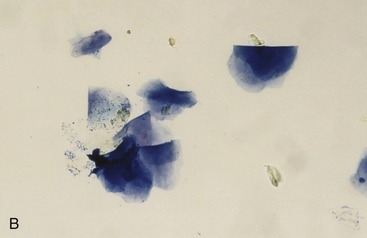

Estrous behavior usually is distinct and easy to recognize. Some queens will, however, have a more diffuse behavior. Grasping the queen in the neck skin and scratching around the tail usually results in lordosis and treading of the hind legs in a queen in estrus. Vaginal cytology is a useful method to diagnose elevated estradiol concentrations indirectly, indicating estrus. Estradiol causes cornification of the vaginal cells. The queen is firmly held by the neck skin in order to collect a vaginal cytological sample. A cotton swab is moistened with saline, inserted in the vestibulum, and rolled to catch the vaginal cells. The cotton swab is rolled over a microscopic slide that is then stained with Diff Quick. During estrus more than 80 per cent of the vaginal cells are cornified (Figure 80-2). It is important to remember that vaginal cytology sampling can cause ovulation as a result of the vaginal stimulation; therefore the queen should be bred within 49 hours after sampling if breeding is intended during the same estrus. Analysis of serum or plasma estradiol also can be used to monitor ovarian function. An estradiol concentration greater than 70 pmol/L is indicative of estrus.11 Although there are individual variations, the first rise in estradiol often precedes estrous behavior by 1 to 4 days and the cornified vaginal smear by approximately 2 to 3 days. Estrous behavior often continues a few days after estradiol has returned to basal levels.11

FERTILIZATION AND IMPLANTATION

Ovulation usually is completed 25 to 32 hours after mating, and fertilization occurs shortly thereafter.26,27 The embryos have reached the uterus on day 6 after mating.27 The preimplantation phase lasts from fertilization until approximately day 12.5 after mating, when the embryos are hatched from the zona pellucida and come in contact with the endometrium, leading to initiation of the implantation process.28 The trophoblast cells start to invade the endometrium on day 14, and on day 16 the embryos are attached and can not be flushed from the uterus.28,29 The placenta is endotheliochorial and zonary. At either end of the placental girdle are the marginal hematomas forming brown borders.28

SUPERFETATION

Superfetation occurs when a mating during pregnancy results in a new pregnancy, leading to fetuses of different ages in the uterus. Ovarian follicular activity also can be observed during the luteal phase, and these follicles therefore may be associated with elevations of estradiol.13 Females sometimes show estrous behavior and allow mating during pregnancy. There are, however, no confirmed cases of superfetation in cats.

SUPERFECUNDATION

Superfecundation occurs when there are multiple fathers to a litter. Matings up to 49 hours after induction of ovulation can result in pregnancy, and the length of life of spermatozoa must be at least 32 hours (the interval between mating and ovulation) because a single mating may result in pregnancy.25 Therefore the oocytes can be fertilized by matings up to 49 hours after the mating that caused ovulation, while it is not known how long spermatozoa from matings before this time can survive in the female genital tract. Superfecundation is common in cats allowed to roam freely and is more common in dense populations. In one study, 76 per cent of all litters of free-roaming queens in a dense population had more than one father, and five different fathers for six kittens was observed for one litter.30

GESTATION LENGTH

The gestation period ranges between 57 and 71 days, with an average of 63 to 66 days. Although unusual, birth of live kittens has been reported after a gestation length of only 50 days.31 More than 95 per cent of all pregnancies have been reported to be within the interval of 61 to 69 days, and more than 90 per cent within 63 to 67 days.31 Large litter sizes may be associated with a shorter gestation length than for small litters.31 There seems to be some genetic influence in the duration of pregnancy as demonstrated by breed and line differences, with the Korat breed having the shortest mean gestation length (63 days) and the Siamese and Oriental breeds the longest (66 days).31,32 Increased mortality has been observed in kittens born before day 63, indicating that they may be premature.4 The more the length of the pregnancy deviates from the normal range, the higher is the risk that the kittens will not be viable.31

PREVALENCE AND CAUSES OF DYSTOCIA

Dystocia is not uncommon in the pure-bred queen, although the frequency seems to vary between breeds. In a colony with research cats of mixed origin, the frequency was only 0.4 per cent, while the mean for pure-bred cats is around 8 to 14 per cent, with 6 to 8 per cent of litters delivered by cesarean section.31,33 The Siamese breed seems to have a higher incidence than other breeds.31,33,34 In one study, there was no connection between small litter size and dystocia, while another study found that a small litter size increased the risk of dystocia.31,34 Most dystocias (67 per cent) are of maternal origin, with the majority caused by uterine inertia (61 per cent). A small birth canal is the second most common maternal cause of dystocia (5 per cent) and can be caused by previous fractures, a vaginal tumor, or by the fact that the queen is young and immature. Fetal malpresentations (16 per cent) and fetal malformations (8 per cent) are the most common fetal causes of dystocia.34

CONCEPTION RATES, LITTER SIZES, AND BIRTH WEIGHTS

The normal conception rate is 70 to 80 per cent.9,12,27,35 The number of kittens varies between one and 13, with a mean of four to five.4,6,12,31,36 Most litters are of one to six kittens, while more than nine kittens is uncommon. Often, the mean number of kittens is lower in the first litter than in subsequent litters.5,36,37 The mean litter size varies between breeds and is larger for the Burmese, Siamese, and Oriental breeds than for the Abyssinian, Somali, Persian, and Sacred Birman breeds.5,31 The number of days on which the queen is mated and the number of matings during estrus does not affect litter size.4 The mean weight of the newborn kittens has been reported to be 100 g ±10 g in the domestic shorthair cat, but often is lower in pedigree breeds and varies with breed from 73 g in the Korat to 116 g for the Maine Coon. Birth weight ranges from 30 to 170 g in all live-born kittens.31,32,38 Festing and Bleby37 found no effect of litter size on birth weight, while Sparkes et al31 found that the birth weight decreased with larger litter sizes.

When cats are bred for optimal production, as in colonies of research cats, two to three litters can be born per year to each queen.36 A decline in reproduction in older queens has been reported in one study, but was not found in another.5,31 An association between age and litter size may, however, be difficult to detect because relatively few old queens are kept for breeding.31 Another reason for a failure to detect a general relationship between old age and low litter size could be that queens who are kept in breeding programs have been shown to be good breeders in their previous litters.

KITTEN MORTALITY FROM BIRTH TO WEANING

The frequency of stillborn kittens varies between catteries and breeds. The mean proportion for all breeds varies from 4.3 to 7.2 per cent.31,36 The percentage of stillborn kittens has been reported to be higher for the Persian breed (11 to 22 per cent) than for other breeds.4,31 The risk of stillborn kittens increases with litter size.31

The proportion of kittens surviving until weaning is around 84 to 87 per cent; however, the survival rate is lower in general for the Persian breed than for other breeds, with approximately 75 per cent weaned successfully.6,31,36 The majority of the kittens who die between birth and weaning are either stillborn or die during their first week of life.31,38 Litters from overweight queens have increased mortality. A small birth weight also increases the risk of neonatal mortality.38 Congenital abnormalities account for a proportion of kitten mortality, while trauma and infections are the most common acquired causes of kitten mortality.38 However, the cause of death often can not be established. The chance of finding an underlying etiological cause increases if whole carcasses are submitted for necropsy examination instead of only tissue samples.38–40 Kittens reared in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) colony had lower mortality, with only 3.3 per cent stillborn and 8.9 per cent total losses until weaning, indicating that control of infections increases kitten survival.37 A summary of reproductive performance in the domestic cat can be found in Table 80-1.

Table 80-1 Reproductive Performance in the Domestic Cat

| Puberty female | 4-21 months, median 9-12 months |

| Puberty male | 6-12 months |

| Duration of estrus | 2-19 days, on average 5 to 8 days |

| Duration of interestrus | Usually 4-22 days |

| Duration of diestrus | 26-55 days, mean 38 |

| Implantation | Days 14-16 after breeding |

| Duration of pregnancy | 95% within 61-69 days |

| Pregnancy rate | 70-80% |

| Birth weight | Mean 73-116 g depending on breed |

| Stillbirths | 4-7% |

| Kitten mortality until weaning | 13-16% (on average higher for the Persian) |

| Litter size | Usually 1-6, range 1-13 (more extreme variations are sometimes reported anecdotally) |

| Dystocia | 8-14% for pure bred cats |

| Weaning | Not before 7-8 weeks. Breeders and cat organizations often prefer that kittens are not re-homed before 12-13 weeks of age. |

NUTRITION

A pregnant queen needs extra energy early in pregnancy. The weight gain is linear until parturition. At the end of gestation, the queen needs 25 to 50 per cent more energy than her normal maintenance needs.41,42 Free-choice feeding will allow the queen to provide herself with adequate nutrition. Only 40 per cent of the total increase in weight is lost at parturition, while the rest is needed as extra reserves for lactation.41

A well-balanced diet is essential for good reproductive performance. The diet should contain at least 32 per cent high-quality protein and 18 per cent fat. Diets that are more calorie-dense (23 per cent vs. 10 to 14 per cent fat) result in slightly larger litter sizes, while depletion of essential fatty acids will result in a reduced number of viable kittens.43,44 Long-term taurine insufficiency will result in increased frequency of pseudopregnancies after mating, fetal resorptions, smaller litter sizes, and stillborn kittens.45 When queens were fed a diet with insufficient copper, the time interval to conception was increased but litter size was not affected.46

LACTATION, PASSIVE IMMUNITY, AND NEONATAL ISOERYTHROLYSIS

Lactation and Weaning

Lactation is the most energy-demanding phase in the reproductive cycle of the queen. She will consume two to three times her normal maintenance energy, but will still lose weight because body reserves are needed to provide enough energy.41,47 Milk production can be observed from 1 to 7 days before parturition. The milk yield varies from 1 to 8 per cent of the queen’s body weight depending on the number of kittens and lactation stage, with a mean of 5 to 6 per cent.47,48 Dentition usually starts around 3 weeks of age, and supplemental kitten food can be given from 3 to 4 weeks of age. Milk alone can support growth until 4 weeks of age.41,49 The age when the kittens start to eat solid food varies between 3 to 5 weeks, with differences between litters.49 Homemade diets for weaning should be avoided because these may have an incorrect balance of nutrients (see Chapter 13). Kittens should not be weaned completely before 7 to 8 weeks of age.41 Some cat organizations recommend that kittens not be separated from their mother before they are 12 to 13 weeks old to promote the proper development of social behavior and immunity before the kitten is sold.50,51

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree