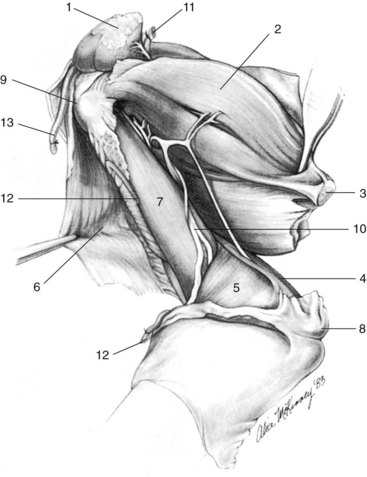

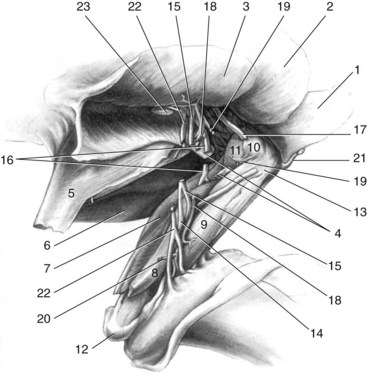

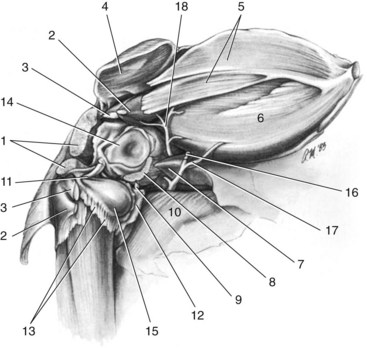

Chapter 65 Amputation of a limb is performed relatively commonly in small animals. It is performed for a number of reasons: (1) tumor of the soft tissues or bone located in a limb that is unresectable without amputation. Amputation remains the standard of care to address the local tumor for osteosarcoma in dogs; (2) severe trauma to the bones, joints, or soft tissues of a limb that is not treatable or that would be otherwise cost-prohibitive for the owners to treat; (3) peripheral nerve problems (such as neoplasia or trauma leading to avulsion of a nerve root) that render the limb nonfunctional, which can lead to self-trauma of the limb; (4) ischemic necrosis of the limb following trauma or formation of a thrombus or thrombi, compromising the vascular supply to the limb; (5) intractable orthopedic or soft tissue infection of the limb; and (6) severe disability due to unmanageable osteoarthrosis or arthritis or congenital deformity.15 The animal should be carefully evaluated before performing the amputation to determine the appropriateness of the amputation for this particular animal and the suitability of the animal for surgery. The other limbs are assessed orthopedically and neurologically. It has been proposed that for animals for which the veterinary surgeon has concerns regarding how the animal might perform with an amputation (e.g., animals that are obese, animals that have advanced degenerative osteoarthritis in the other limbs), the animal can be evaluated by temporarily slinging the affected limb and observing the animal’s response. This test can be misleading in some dogs, for instance, when the dog’s response to having its limb in a sling is poor and yet the dog can perform very well after the amputation. This probably occurs because the dog needs to carry the weight of the limb in an uncomfortable and maybe even painful position. Contraindications to performing an amputation include severe orthopedic or neurologic disease affecting the other limbs and/or extreme obesity.9 Educating the owners before the surgery is very important in helping them making the right decision. The goal is not to persuade them to have the amputation performed even when medically indicated, but rather to make sure they have all the relevant information needed to make a rational decision rather than an emotional one. One study showed that owners were more satisfied with their decision and the outcome of the surgery when amputation was considered properly in advance.9 In helping owners make the decision, providing clear information about the need for the amputation and about its prognosis is essential (see outcome and complications section). For this purpose, slides, pictures, and videos of dogs with an amputated limb can be very helpful.9 However, no matter what decision is ultimately made by the owners, it must be respected by the veterinary health team. General Principles and Considerations For the purposes of this chapter, full limb amputations are discussed. Partial limb amputations are possible; with these procedures, more length of the limb is preserved, so that the amputation is performed at a level distal to what is described in this chapter. Partial limb amputations, other than digit amputations, are discouraged. Partial limb amputations should be reserved for rare cases in which a prosthesis is going to be used.7 Otherwise, even when the lesion is very distal on the limb, a full limb amputation is performed. Leaving excessive length to the limb can lead to pressure sores and adds unnecessary weight that the animal must carry without any purpose or benefit to the animal. Major arteries and veins are divided and ligated individually to prevent the formation of arteriovenous fistulas and to ensure that the ligation of each vessel is more secure. Major arteries are doubly ligated. In giant-breed dogs, the second ligature can be a transfixation ligature for added security instead of a simple encircling ligature. Although double ligation is traditionally reserved for arteries, some surgeons also doubly ligate large veins. Albeit veins are the low-pressure system, the muscularis layer of the veins is considerably weaker than that of the arteries, and slippage of a ligature can occur owing to the flimsy venous wall. It has been proposed that arteries should be ligated first to prevent pooling and loss of blood in the tissues of the limb, as would occur if the veins are ligated first. In cases of malignant neoplasms, it has been suggested to ligate the vein first to limit the possibility of allowing metastasis to occur during surgical manipulation (although this is controversial even in cases of malignant neoplasm).13,15,16 Because of the significant collateral circulation on both the arterial and venous sides in dogs and cats, the benefit of following these recommendations in dogs and cats is unclear. With the goal to provide multimodal analgesia, when nerves are isolated during surgery, they can be injected with 0.5% bupivacaine before they are transected. A 25-gauge needle is used to inject the local anesthetic. The needle is inserted into the nerve and bupivacaine is injected until a bleb develops into the nerve. The nerve is then transected distal to the injection site. Also, wound soaker catheters can be placed in the surgical bed after the limb is removed but before the surgical wound is closed. Soaker catheters are flexible indwelling catheters embedded near or in surgical sites that can be used to deliver continuous infusion of local anesthetics.1 Bupivacaine or lidocaine can be used.1 A skin incision is made circumferentially around the limb. The incision is started at the level of the greater tubercle of the humerus, staying lateral to the limb; it curves distally to the midlevel of the brachium and is directed caudoproximally to end in the caudal point of the axillary space. A straight medial incision is made to connect the cranial and caudal points of the lateral incision. The skin distal to the incision is dissected free from the subcutaneous tissue to the level of the elbow joint circumferentially. The cephalic vein is ligated and divided as it passes cranially under the cleidobrachialis muscle. The axillobrachial vein is ligated and divided as it branches from the cephalic vein. The cleidobrachialis muscle is transected at its insertion on the distal aspect of the humeral crest. The acromion portion of the deltoideus muscle is transected at its insertion on the deltoid tuberosity of the humerus and is reflected proximally. The brachial fascia is incised distally along the cranial border of the lateral head of the triceps muscle to the level of the olecranon. The tendon of the triceps brachii muscle is completely isolated and transected just proximal to the olecranon (Figure 65-1). The branches of the collateral ulnar artery, which supply the distal portion of the triceps brachii muscle, are severed as they enter the long head of the triceps brachii muscle. Branches of the distal radial nerve to the lateral and long heads are transected. The deep brachial artery is still intact and supplies the lateral and long heads of the triceps brachii muscle. The axillobrachial vein is ligated and divided again as it terminates in the axillary vein (Figure 65-2). The final step is division of the muscles close to the joint. This dissection is started by transecting the insertion of the supraspinatus muscle from the major tubercle of the humerus. The joint capsule is incised along with the muscle. The insertions of the infraspinatus and teres minor muscles are transected from the humerus. After the aponeurosis of the lateral head of the triceps brachii muscle is elevated or transected from the humeral crest, the incision in the lateral joint capsule is continued caudally and around the joint to the medial side, where the subscapularis muscle is transected from its insertion on the minor tubercle of the humerus. The incision is continued cranially and transects the tendon of origin of the coracobrachialis muscle and finally the tendon of origin of the biceps brachii muscle (Figure 65-3).

Amputations

Surgical Techniques

Thoracic Limb

Amputation by Disarticulation at the Scapulohumeral Joint11,15

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Amputations

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue