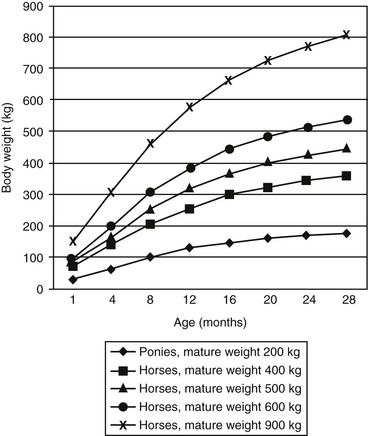

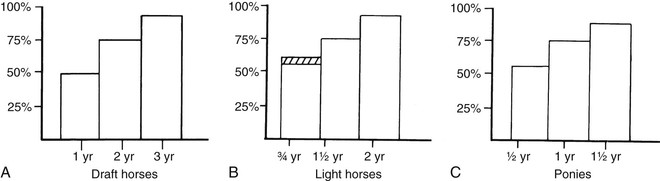

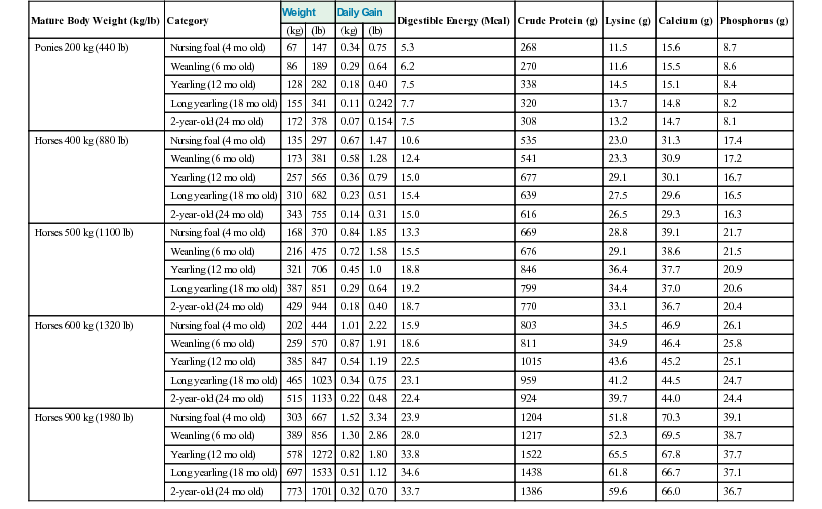

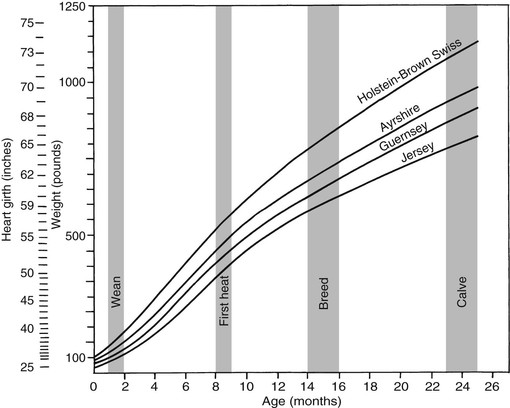

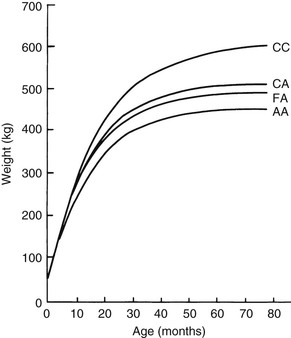

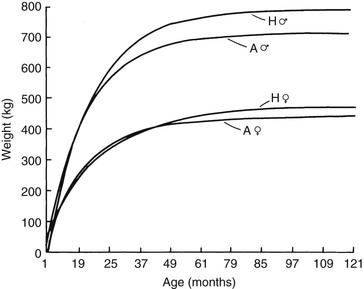

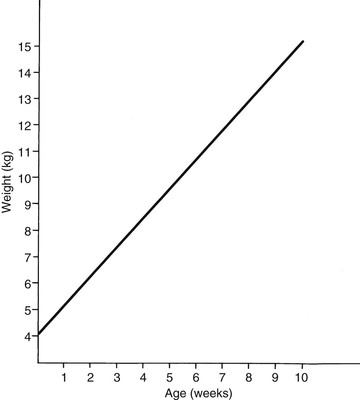

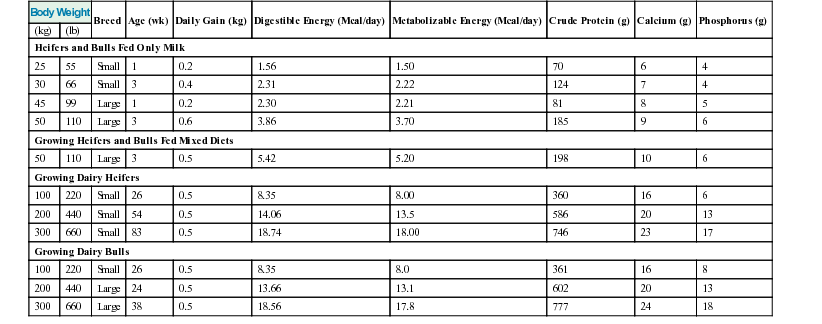

Meri Stratton-Phelps, Consulting Editor John Maas Slowed growth and below-normal weight gain usually happen at the same time, although occasionally they develop separately. By definition a decrease in growth and weight gain is limited to the growing animal. Similar pathogenic mechanisms cause weight loss or an emaciated condition in an adult patient. This arbitrary age division allows the clinician to consider possible causes that are more or less common for a given age group. Potential growth and weight gain are genetically determined. They differ according to species, breed, and sex, and marked differences in potential growth exist within a breed. The potential for growth in ruminants is greater in the offspring of multiparous females than in those from primiparous females. The normal or minimum growth and weight gain rates for common breeds of the various large animal species are outlined in the section on assessment of growth and weight gains. Major pathogenic mechanisms that result in decreased growth and decreased weight gain include the following: • Inadequate dietary intake of essential nutrients • Genetic errors in metabolism or physiologic function Inadequate intake of one or more essential nutrients is an important cause of decreased growth. In many cases growing animals are not provided with a sufficient volume of feed to meet their nutrient requirements. Young animals rely on a highly digestible diet that provides energy and essential nutrients for growth. Even animals fed an appropriate volume of a poor-quality milk replacer could suffer from poor growth. Milk replacers formulated with sources of protein, fat, vitamins, and minerals that have limited nutrient digestibility may induce a state of energy, protein, vitamin, or mineral malnutrition. For some young animals, poor-quality forage is the only feed available. Weaned foals and ruminants rely on forages and cereal grains to provide essential nutrients. Hay that has been harvested at a late stage of growth usually has a lower nutrient digestibility compared with young forages. Diets low in digestible energy or protein or both reduce total daily intake in ruminants (Table 9-1) because of the increased turnover time (T1/2) in the gastrointestinal tract and subsequent decreased throughput. This compounds the problems caused by an inadequate intake of digestible nutrients. The digestibility of forages is even lower for horses than for ruminants. TABLE 9-1 Maximum Dry Matter Intake (DMI) Related to Forage Quality for Cattle From Maas J. 1987. Relationship between nutrition and reproduction in beef cattle. Vet Clin North Am 3:634. Protein-calorie malnutrition (PCM) is the most common clinical cause of decreased growth and decreased weight gain in young animals. It is characterized by smaller size and lower weight than the normal minimums for age, breed, and sex. Inadequate intake of digestible energy and protein (or essential fatty acids in the neonate primarily adapted to a milk diet) results in inadequate levels of amino acids, fats, and carbohydrates for normal metabolism and growth. Diets that lack any of the other essential nutrients (essential fatty acids, vitamins, macrominerals, or trace minerals) can also decrease growth. Deficiencies of calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium result in improper skeletal formation. Deficiencies in other macrominerals (e.g., sodium, chloride, potassium), trace minerals (e.g., copper, zinc, manganese, cobalt, iron), and vitamins (e.g., A, D, E, thiamin) cause biochemical dysfunctions that lead to inefficient metabolism and growth. Large animal patients that grow slowly as a result of inadequate diets often have normal or increased appetites until they are terminally ill. Physical findings and clinicopathologic data from animals with PCM are often within the normal range until the disease process is well advanced. Infections or inflammatory processes are important causes of decreased growth and decreased weight gain in young horses and ruminants. The decrease in growth can be of short duration followed by recovery and compensatory gain (cryptosporidiosis) or can persist (chronic bronchopneumonia). Infections or inflammatory processes can also result in nutrient malabsorption (chronic salmonellosis, acute rotavirus diarrhea, equine proliferative enteropathy), anorexia (pharyngeal abscesses, systemic disease), increased nitrogen turnover, and direct protein losses (gastrointestinal disease). Both energy and protein requirements may be increased as a result of infection and inflammation. Parasitism often affects young horses and ruminants and results in decreased growth and decreased weight gain by increasing nutrient requirements, increasing nutrient losses, and/or decreasing nutrient absorption. The animal’s metabolic rate and nutrient requirements may also increase as a result of inflammatory and immune reactions that arise secondary to parasitism. Genetic diseases (α-mannosidosis, dwarfism) result in decreased growth through generalized errors in the genetic code or interference with strategic reactions in one or more metabolic pathways. Congenital cardiac malformations (tetralogy of Fallot, interventricular septal defect) create physiologic inefficiencies that require energy beyond the body’s ability to supply it. Congenital renal disease (agenesis, dysplasia, hypoplasia, polycystic kidney disease) affects homeostatic mechanisms that regulate electrolyte and acid-base balance, results in the production of uremic toxins, and often results in partial anorexia and PCM. Digestive tract malformations including cleft palate, megaesophagus, and brachygnathism can reduce nutrient ingestion and impair growth. Toxicities, although rare in growing animals, result in decreased weight gain by interfering with metabolic pathways (e.g., ammonia toxicity, zinc-induced copper deficiency with abnormal skeletal development in foals), by causing loss of body reserves (e.g., thiamin deficiency in horses, bone marrow hypoplasia and associated bleeding diatheses in ruminants associated with bracken fern toxicity), by inducing anorexia, or by a combination of mechanisms. The pathogenic mechanisms of many toxins are not yet known. Environmental factors including extreme heat or cold or high humidity result in decreased growth and decreased weight gain. Extremely cold conditions increase an animal’s daily energy requirements. During extremely hot weather feed intake often decreases, which may contribute to decreased growth. Often, environmental conditions influence the development of disease, resulting in a subsequent increase in nutrient requirements in a growing animal (e.g., calves with PCM housed in poorly ventilated or overly humid conditions become much more susceptible to infectious pneumonia). In many cases a combination of these diverse factors may influence the growth and weight gain of young animals. A period of increased growth rate and weight gain, called compensatory gain, often occurs after a period of restricted growth once adequate dietary energy and protein are available. In growing foals, compensatory gain should be closely monitored to prevent rapid growth and abnormal skeletal development, which could lead to developmental orthopedic disease. Boxes 9-1 and 9-2 list many of the possible causes of decreased growth and decreased weight gain in horses and ruminants, respectively. 1. Take a general history and a diet history. b. Diet history ii. Weanling: When was the foal weaned? Does the foal compete with other foals for feed? Has the owner changed the foal’s diet recently? If yes, what changes were made? Does the foal have a good appetite? Has the foal’s appetite changed recently? 2. Perform a physical examination. a. What is the body weight of the foal (measured by using either a scale or weight tape if the foal is 3 months of age or older)? What is the body condition score (BCS) of the foal (see Table 9-22)? Is the foal small, thin, or underweight according to growth charts (Table 9-2; Figs. 9-1 and 9-2)? b. Does the foal have evidence of a congenital abnormality (cardiac, renal, gastrointestinal, oral)? c. Does the foal show any signs of infectious disease (current or resolved)? d. Does the foal have any musculoskeletal abnormalities? 3. Examine the feces. What is the consistency of the feces? Refer to Chapter 17 for the diagnosis and management of neonatal diarrhea; refer to Chapter 7 if the foal is older and has evidence of diarrhea. Is there evidence of sand in the manure? Perform a fecal egg count. If the foal has a positive fecal egg count, follow the parasite control program recommendations in Chapter 49. If a negative fecal egg count is reported but parasitic infestation is still suspected, repeat the test in 2 to 3 weeks or follow the deworming protocols in Chapter 49. Evaluate the feces for occult blood. If the foal has a positive fecal occult blood test, review the medical management for melena in Chapter 7. a. Perform a complete blood count (CBC) and include a plasma protein and fibrinogen concentration. If the foal is anemic, determine the cause of the anemia following the guidelines in Chapter 24. If the foal’s CBC indicates inflammation, review Chapters 25 and 26 and select appropriate ancillary diagnostic tests to identify the source of the infection or inflammation. 5. Analyze the diet and improve the feeding program. a. Determine whether the energy, protein, mineral, and vitamin content of the diet meets the requirements of the growing foal (Table 9-3). Use the Nutrient Requirements of Horses free companion computer program as a reference for all essential nutrients (www.nap.edu, search word “horse”). i. Dietary protein and essential amino acids are especially important in young growing horses. Lysine is the first, and threonine is the second limiting amino acid in the equine. Growing foals should consume 4.3% of their crude protein requirement as lysine (multiply the crude protein requirement by 4.3%).6 Growing foals should also consume at least 0.5% threonine dry matter (DM) in their diet. Soybean meal and alfalfa hay contain approximately 3.3% and 0.9% lysine (DM), respectively. Cereal grains are poor sources of lysine. iii. Forage: Determine the nutrient content of forage or pasture with an analysis. Forage sampling instructions and forage analysis companies are listed in Boxes 9-3 and 9-4. University extension services often provide a forage analysis service. If the client does not purchase a large volume of hay, or if analysis cannot be performed, forage tables from the Nutrient Requirement Council reference books (www.nap.edu) and nutrient tables from the Equi-Analytical Laboratories forage laboratory database (www.equi-analytical.com) can be referenced to estimate the concentration of different nutrients in common forages and supplemental feeds. Use the daily nutrient requirements (see Table 9-3) to recommend the type and amount of forage the foal should consume on the basis of the nutrient content of the forage. 1. Take a general history and a diet history. ii. Identify the problem as acute, subacute, or chronic. iii. Check for signs or history of previous infectious disease in the herd. iv. Determine the parasite control procedures for the animal or herd. b. Diet history 2. Perform a physical examination. a. Determine the patient’s age and weight. Is the patient growing appropriately on the basis of age and weight charts (Figs. 9-3 to 9-6)? b. Does the animal show any signs of infectious or parasitic disease? c. Does the animal show any signs of congenital abnormalities? 3. Examine the feces. Perform flotation, sedimentation, and Baermann’s procedures to detect patent parasitic infestation. Perform a fecal occult blood test; if the result is positive or if there is evidence of diarrhea, see the section melena or diarrhea in Chapter 7. If diarrhea is noted in neonatal calves, refer to Chapter 20 for diagnostic and therapeutic management. 5. Analyze the diet and improve the feeding program. Compare nutrient intake with the requirements for maintenance and growth of the various ruminant species (Tables 9-4 through 9-11). If the neonate is being fed a milk diet, evaluate the quality of the product and ensure that the animal’s intake meets the dietary requirements (see Tables 9-4 and 9-5). Requirements for other breeds and life stages can be found in the nutrient requirement textbooks for dairy cattle, beef cattle, and small ruminants. Ensure that the milk replacer is mixed properly. If the ruminant is consuming a grain mix or forage, ensure that the quantity and the quality of the feed are adequate to allow sufficient intake in developed ruminants (see Table 9-1). Forage sampling instructions are listed in Box 9-3. If anorexia is present, look for more specific signs of a primary disease process. If the diet supplies adequate nutrients for maintenance and growth, consider decreased growth and decreased weight gain to be caused by a primary disease condition. TABLE 9-4 Daily Energy and Protein Requirements for 50-kg Calves on a Milk Diet * A 50-kg calf gaining 0.75 kg/day would have a daily energy requirement of 5000 kcal of digestible energy (2750 kcal maintenance + 2250 kcal/0.75 kg of gain). † A 50-kg calf gaining 0.75 kg/day would have a daily protein requirement of 190 g of digestible protein (25 g of maintenance + 165 g of gain). TABLE 9-5 Net Energy (NE) Requirements of Young Lambs on Milk-Replacer Diets* * Protein requirements for young lambs on a milk-replacer diet are approximately 20 g, 40 g, and 60 g for weight gains of 0, 100, and 200 g/day, respectively. NEg, Net energy of gain; NEm, net energy of maintenance. From Chiou PWS, Jordan RM. 1973. Ewe milk replacer diets for young lambs. IV. Protein and energy requirements of young lambs. J Anim Sci 37:581. TABLE 9-7 Net Energy (NE) Requirements for Growth of Beef Cattle (Mcal/day)

Alterations in Body Weight or Size

Mechanisms of Decreased Growth and Decreased Weight Gain

Forage Quality

Maximum DMI/Day (% Body Weight)

Maximum DMI for 500 kg/Cow/Day (kg)

Poor

1-1.5

5-7.5

Oat straw

Corn stover

Average

2

10

Meadow grass hay

Excellent

2.5

12.5

Alfalfa hay (25% crude fiber)

Corn silage

Approach to the Diagnosis and Management of Decreased Growth and Decreased Weight Gain in Horses

Approach to the Diagnosis and Management of Decreased Growth and Decreased Weight Gain in Ruminants

Digestible Energy Requirements

Digestible Protein Requirements

Maintenance

45-55 kcal/kg body weight

0.5 g/kg body weight

Gain

300 kcal/100 g gain in body weight*

22 g/100 g of weight gain†

0.5 kg daily gain

1500 kcal

1 kg daily gain

3000 kcal

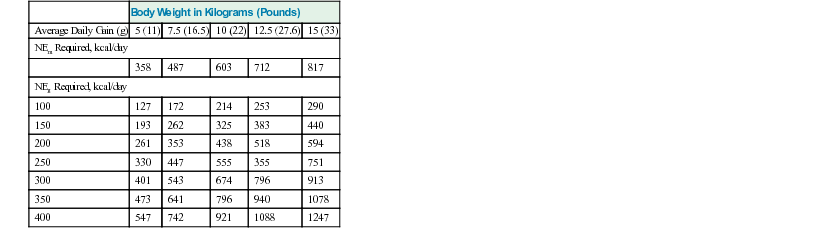

Body Weight in Kilograms (Pounds)

Average Daily Gain (g)

5 (11)

7.5 (16.5)

10 (22)

12.5 (27.6)

15 (33)

NEm Required, kcal/day

358

487

603

712

817

NEg Required, kcal/day

100

127

172

214

253

290

150

193

262

325

383

440

200

261

353

438

518

594

250

330

447

555

355

751

300

401

543

674

796

913

350

473

641

796

940

1078

400

547

742

921

1088

1247

Body Weight (kg); (NEm Required)

Daily Gain (kg)

200 (4.1)

250 (4.84)

300 (5.55)

350 (6.23)

Medium-Frame Steer Calves NEg Required

0.5

1.27

1.50

1.72

1.93

1.0

2.72

3.21

3.68

4.13

1.5

4.24

5.01

5.74

6.45

Body Weight (kg); (NEm Required)

Daily Gain (kg)

300 (6.38)

400 (7.92)

500 (9.36)

600 (10.7)

Growing Bulls NEg Required

0.5

1.72

2.13

2.52

2.89

1.0

3.68

4.56

5.39

6.18

1.5

5.74

7.12

8.42

9.65 ![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Alterations in Body Weight or Size

Chapter 9