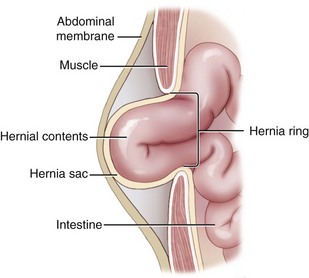

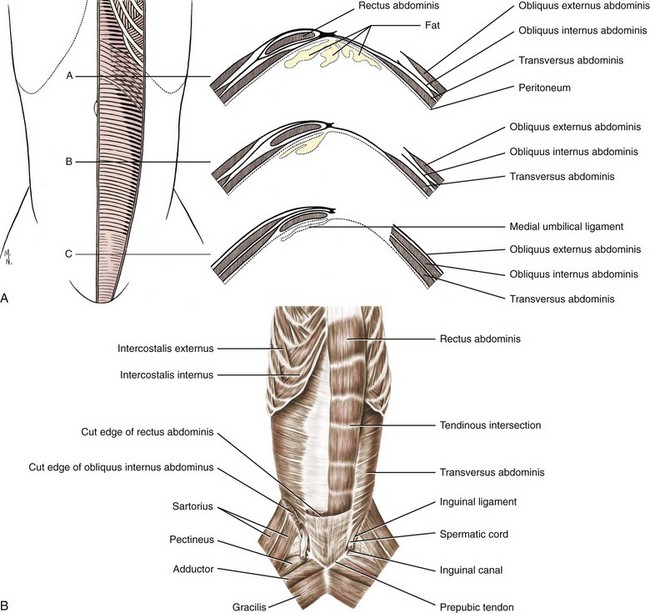

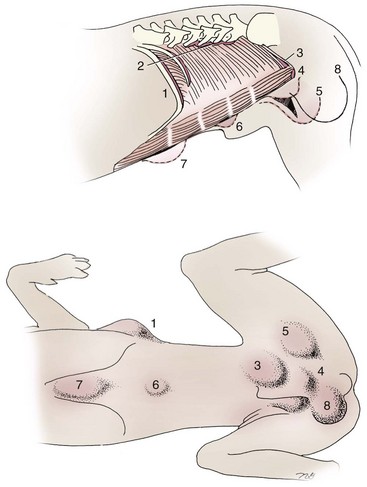

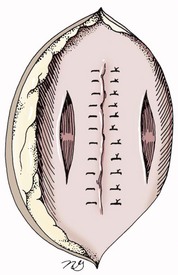

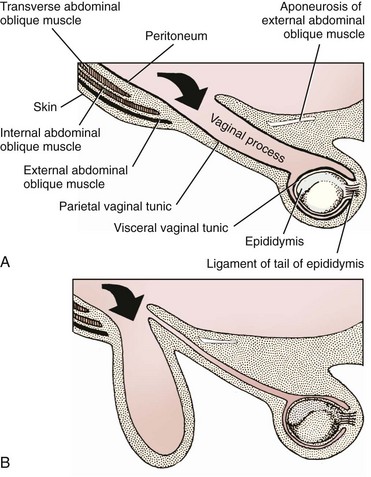

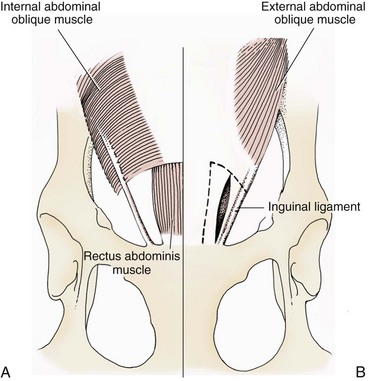

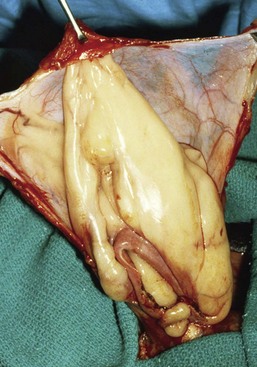

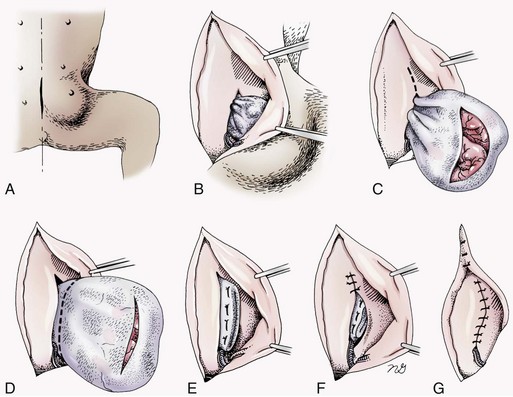

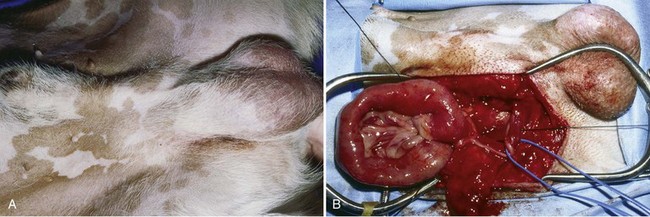

Chapter 84 A hernia is composed of a ring (the anatomic limits of the wall defect), sometimes a sac, and the protruding contents (Figure 84-1). The ring may be confined within a normal aperture in the abdominal wall (considered a true hernia) or may occur in other areas (false hernias) as a result of trauma or through a disrupted surgical approach (an acquired hernia). Very large hernial rings or small defects rarely cause clinical problems; however, hernias just large enough to entrap viscera and obstruct blood supply to the contents (strangulation) are most dangerous to the patient. Contraction of scar tissue at the hernial ring during the healing process may cause a delay in onset of clinical signs as the organs become entrapped (incarcerated) or obstructed. Whereas in developmental (congenital) hernias, the hernial sac is a mesothelial membrane (peritoneum) covering the contents, in acute traumatic or incisional hernias, no sac is present. Over time, a peritoneal sac may form over the contents of chronic traumatic or incisional hernias; this process is termed peritonealization. Hernial contents without a mesothelial covering are at risk for developing adhesions that restrict movement of the contents (irreducible hernias); this may lead to obstruction or torsion of the protruding tissue. Traumatic hernias most often occur from blunt trauma with avulsion of muscle fascia or penetrating injury. When a traumatic abdominal hernia caused by a fractured rib penetrating through the paracostal musculature results in organ herniation, it is termed an auto-penetrating hernia.41,106 Contents of a hernia may be predicted based on the site of the defect (e.g., inguinal hernias often have the uterus involved because of the tethering effect of the round ligament) or more mobile structures such as the omentum or intestine can travel longer distances into nearly any abdominal hernia site. The tough abdominal wall confines the abdominal organs within the largest cavity in the body, extending from the diaphragm to the pelvic canal (Figure 84-2). The arrangement of the aponeuroses of abdominal muscles, their attachments, and fiber direction are important to understand when attempting hernia reconstruction. Fibers of the tendinous aponeuroses of the external abdominal oblique, internal abdominal oblique, and transverse abdominal muscles converge and join on midline to form a thick white band, termed the linea alba, which is located between the rectus abdominis muscles. The linea alba is widest in the cranial abdomen, and it narrows considerably before it attaches to the pubis by the prepubic tendon (sometimes termed the cranial pubic ligament). Fibers of the flat tendinous aponeuroses of abdominal wall muscles pass either superficially or deep to the rectus abdominis muscles that extend in a cranial and caudal direction from the first costal cartilage to the pecten of the pubis. The external abdominal oblique aponeurosis always runs superficial to the rectus abdominis muscle. The location of the aponeurosis of the internal abdominal oblique varies along the length of the abdomen. In the cranial third of the abdominal wall, fibers pass both deep and superficial to the rectus abdominis muscle. From the umbilicus caudally, all of the internal abdominal oblique fibers run superficial to the rectus abdominis muscle. Fibers of the transverse abdominal muscle pass deep to the rectus abdominis muscle in the cranial two thirds of the abdominal wall, but in the caudal third, fibers run superficial to the rectus abdominis muscle. Whereas the external rectus sheath contains tendinous aponeuroses of the abdominal muscles that run superficial to the rectus abdominis muscle, the internal rectus sheath is composed of sheets of fascia that are deep to this muscle. The external rectus sheath has been shown to be the primary strength-holding layer throughout ventral midline closures.101 Although hernias can occur virtually anywhere in the abdominal wall, most defects are found in select areas (Figure 84-3). Cranial ventral midline hernias are most often congenital in origin and include umbilical hernias and substernal (or ventral) hernias. Defects in the more lateral areas of the abdominal wall most often result from trauma and include the paracostal defects just off the caudal rib margin or dorsal lateral hernias found just ventral to the lumbar transverse processes. Caudal abdominal hernias include congenital scrotal and inguinal hernias and those most often caused by trauma—the prepubic and femoral hernias. The overall success of a hernia repair (and often the prognosis for the patient) rarely depends on the repair itself but more on management of the sequelae to organ herniation or internal damage from trauma that impair normal body function. The severity of functional alteration depends on the cause, location, and content of the hernia. Important, often life-threatening, sequelae associated with abdominal hernias can be attributed to space-occupying effects (known as loss of domain), incarceration or obstruction, or strangulation. The clinical condition of the animal at presentation, whether the hernia is open to the outside or not, concurrent injuries to distant structures, and organ compromise from the trauma must also be factored when attempting to predict patient outcome.106 “Loss of domain” occurs when the abdominal wall has become accustomed to a relatively small intraabdominal volume because of organ displacement outside the cavity (usually through a large defect). Manual reduction of the hernia contents and primary closure of the defect is difficult or impossible in this situation. Repair of the restricted abdominal wall by forcing the herniated contents back into the abdomen results in excessive tension on the repair, increasing the risk of recurrence. Even more deleterious are acute pulmonary complications, secondary to restriction of diaphragm function, and poor organ perfusion (abdominal compartment syndrome).57,59 High intraabdominal pressure has been documented in a series of client-owned dogs undergoing abdominal surgery, necessitating surgical decompression; one case occurred after hernia repair.21 Several techniques have been used in humans to reduce complications from loss of domain by using a tissue expansion principle.15,17 Progressive pneumoperitoneum and tissue expansion with inflatable Silastic expanders gradually stretch the abdominal wall in much the same way as pregnancy. Staged reduction of open congenital abdominal defects with a Silastic sac has achieved excellent results with little mortality in infants. Most adult human patients with loss of domain are repaired using prosthetic materials (e.g., mesh) to help span the defect; this avoids tension and reduces hernia recurrence and postoperative complications related to loss of domain.17,60 Incarceration of organs such as the intestine, uterus, or bladder most often alters normal function because of luminal obstruction. Acutely incarcerated organs are irreducible and can become lethal strangulated obstructions within hours; therefore, urgent repair should be considered in this situation. The severity and onset of the clinical signs related to the incarcerated obstruction often depends on the contents of the hernia and size of the defect. Abdominal defects with small, inelastic hernial rings, such as scrotal or femoral hernias, are at high risk for incarceration and strangulation.120 The threat of complication and death is 50% higher in humans with incarcerated or strangulated hernias than in hernias containing reducible viable tissue; therefore, early diagnosis and surgical correction of incarcerated hernias is critical to prevent life-threatening sequelae relating to organ devitalization. Sequelae to hernia strangulation vary depending on chronicity and the organ involved. Strangulated umbilical, inguinal, femoral, and prepubic hernias most often contain falciform ligament or omentum, uterus, prostatic fat, and urinary bladder, respectively.108,120 The clinical course of affected patients depends on the degree of vascular compromise, volume of body fluids lost from obstruction or sequestration, and absorption of bacteria and toxins. The presence of strangulated, contaminated hollow viscus may result in significant blood, protein, and fluid loss and often rupture, causing rapid toxemia and septicemia. Bacteria migrate transmurally through devitalized intestine even before evidence of gross spillage occurs.10 Before overt signs of infection or contamination occur, vasoactive substances such as arachidonic acid metabolites, cytokines, leukotrienes, and kinins from tissue and blood cell autolysis cause redistribution of body fluids and severe cardiopulmonary effects.16 Strangulated viscera within external abdominal hernias may be more isolated from the vascular system than those strangulated within the peritoneal cavity. Liberated vasoactive substances are not absorbed as quickly through the subcutaneous tissue as the permeable abdominal cavity; thus, patients with external strangulated hernias may have a more delayed onset of clinical signs and shock. Severely compromised patients often decompensate and die under anesthesia during attempts at surgical reduction and repair of strangulated hernias; this is thought to be caused by rapid release of vasoactive substances into the circulation from necrotic strangulated organs during surgical reduction. En bloc resection of the devitalized herniated tissue, with release of the constricting ring only after the vascular supply is occluded, may help reduce this fatal complication.108 In an embryo, the abdominal wall is formed by migration of cephalic, caudal, and lateral folds. The umbilical aperture, which serves as a passageway for the contents of the cord (umbilical blood vessels, small vitelline duct, and stalk of the allantois), remains after normal migration and fusion of these folds.62 The umbilicus is a cicatrix identifying the previous attachment site of the umbilical cord in a fetus. In mature animals, the falciform ligament (the remnant of the umbilical vein) and middle umbilical ligament of the bladder (the remnant of the urachus) are attached to the internal aspect of the umbilicus.35 Congenital umbilical hernias result from failure of fusion or delayed fusion of the lateral folds (principally, the rectus abdominis muscle and fascia) at the umbilicus after normal return of the midgut from the umbilical cord in the canine fetus, which normally occurs at the sixth week of gestation.62 Most umbilical hernias are inherited and are probably the result of a polygenic threshold character, involving a major gene whose expression is mediated by the breed background.51,99 Until more is known about the inheritance and expression, affected dogs or cats should not be bred. Umbilical hernias have been associated with fucosidosis, an inherited, autosomal recessive, neurovisceral lysosomal storage disease.115 Of 31 English Springer spaniels with fucosidosis, 10 had umbilical hernias, and one had a scrotal hernia. This hernia has also been associated with a congenital, sex-linked, recessive disorder in dogs called ectodermal dysplasia.79 Cryptorchidism frequently coexists in dogs with umbilical hernias or other congenital defects.9,90 Congenital cranioventral abdominal hernias, incomplete caudal sternal fusion, and umbilical defects with concomitant diaphragmatic hernias of various types occur in dogs.81 Successive breedings of a Labrador retriever and an American foxhound with these defects created ratios of affected offspring suggestive of an autosomal recessive mechanism.36 Developmental causes were also suspected in a litter of cocker spaniels with diaphragmatic, cardiac, and abdominal wall defects similar to thoracoabdominal ectopic cordis syndrome.8 In humans, cardiac malposition may result in a mesodermal defect characterized by partial or complete failure of transverse septum development and supraumbilical fusion failure.25,28,62 Defects associated with infraumbilical midline hernias in humans include exstrophy (abdominal wall protrusion) of the bladder, hypospadias, and imperforate anus.62,103 Findings such as these suggest that a thorough search for other congenital defects is important when examining patients with umbilical hernias. Omphaloceles are large midline umbilical and skin defects that permit abdominal organs to protrude from the body. Herniated contents are initially covered by a transparent membrane (amniotic tissue) attached to the edges of the umbilical defect until minor trauma ruptures the membrane, exposing the prolapsed contents to contamination (Figure 84-4).25,56,62 The incidence of these defects is difficult to determine because most affected animals either die or are destroyed without veterinary attention. Attempted surgical repair in one litter of 5-day-old kittens was unsuccessful because tension sutures pulled through the thin abdominal wall.56 Gastroschisis grossly appears like an omphalocele, but the defect is paramedian. This anomaly has been reported in cats and often results in early neonatal death.25 Umbilical hernias are the most common abdominal hernias in small animals. In an epidemiologic study involving congenital abnormalities found in pet store dogs over a 2-year period, umbilical hernias were found in 0.6% (10 of 1679) of animals.102 Airedale terriers, basenjis, Pekingese, pointers, and Weimaraners are at greater risk.51 The incidence of umbilical hernia is about the same in cats and dogs when the aforementioned dog breeds at risk are excluded.99 A high incidence of umbilical hernia was noted in one family of Cornish rex cats.99 There is no sex predilection for umbilical hernia in the general population; however, females of predisposed dog breeds have a greater incidence of umbilical hernia for unknown reasons.51,99 Clinical Signs: Umbilical hernias usually appear as a soft, round mass or swelling at the umbilical scar. The swelling may feel firm if fat or another structure becomes entrapped and irreducible (Figure 84-5). Animals with acute gastrointestinal signs (vomiting, anorexia) and a firm, irreducible, painful umbilical mass may have entrapped viscera causing obstruction. Diagnosis: Owners usually identify animals with obvious, large umbilical hernias soon after birth. A patient’s history and location of the lesion usually leave little doubt about the diagnosis, although smaller hernias require careful inspection and palpation. Examination of the animal in dorsal recumbency facilitates reduction of the contents of the hernia and hernial ring palpation. Be aware that other masses located in the region of the umbilicus in the puppy or kitten may appear like an umbilical hernia.22 Treatment: Most small, reducible umbilical hernias in dogs and cats contain only falciform fat and are of little clinical significance. Initially, healthy puppies with small (<2 to 3 mm) hernias are treated conservatively because spontaneous closure has been reported as late as 6 months of age.97 Affected animals are neutered because of genetic predisposition to this disease. Most umbilical hernias can be primarily closed with tension-relieving suture patterns. If the edges of the hernia cannot be apposed easily with thumb forceps, reliance on sutures alone to relieve wound tension is not recommended. Use of a Mayo mattress (“vest over pants”) suture pattern for herniorrhaphy is controversial.37,80,109 This pattern permits more contact with apposing wound edges but, in doing so, increases unwanted tension on the repair. Primary side-to-side repairs in humans are superior if wound edges can be apposed without tension.37 In rare situations, absence of a region of the abdominal wall accompanies large umbilical hernias. Releasing incisions can be made to reduce tension on the primary suture line, provided that the rectus muscles and underlying fascia have adequate strength (Figure 84-6). Incisions are made at least 2 cm away from the defect through the external rectus fascia only. The fascia is elevated or dissected off the rectus abdominis muscle and shifted toward the midline, thereby reducing tension on the primary repair. Alternately, a component separation technique can be utilized to allow a tension-free midline closure.95 The author prefers to use prosthetic materials for reconstruction of very large, clean defects rather than rely on shifting local tissues such as fascia (see Reconstruction of Large Abdominal Hernias later in this chapter). Aftercare and Prognosis: Minimal postoperative care is required after uncomplicated repair of umbilical hernias. Observation and care of the wound and exercise limitation are routine. Patients with uncomplicated hernias have an excellent prognosis. More complicated hernias (those that are multiple, strangulated, or open at birth) have a guarded to poor prognosis, depending on the patient’s status before surgery, the nature of the herniated contents, and the extent of the defect. Caudal abdominal hernias include defects in the inguinal, scrotal, and femoral regions. True hernias in the inguinal region are categorized as direct or indirect. With indirect hernias, the abdominal viscera enter the cavity of the vaginal process (Figure 84-7). With direct hernias, the less common form in humans and small animals, organs pass through the inguinal rings adjacent to the normal evagination of the vaginal process.47,125 Direct hernias are usually large, and most do not cause incarceration or strangulation.120 In contrast, indirect inguinal hernias in male dogs (scrotal hernias) more often cause organ dysfunction because the vaginal process narrows considerably at the relatively inelastic inguinal ring. Inguinal hernias are less common than umbilical hernias. They result from a defect in the inguinal ring through which abdominal contents protrude.85,125 Inguinal hernia generally denotes direct and indirect hernias in females and direct hernias in males. Indirect hernias in males are considered separately as scrotal hernias. Congenital inguinal hernias in dogs and cats are rare and often coexist with umbilical hemias.9,51,93 Basenji, Pekingese, poodle, basset hound, Cairn terrier, Cavalier King Charles spaniel, Chihuahua, cocker spaniel, dachshund, Pomeranian, Maltese, and West Highland white terrier breeds are predisposed.9,51 Congenital inguinal hernias develop more often in male dogs than in females, possibly because of delayed inguinal ring narrowing from late testicular descent.38,54,120 Acquired inguinal hernias are relatively common in dogs and most often involve middle-aged, intact bitches.83,85,98,120 No breed predilection has been documented,125 although toy-breed dogs and Shar-Peis may be overrepresented. In one case series, female dogs with inguinal herniation were older and significantly lighter than affected male dogs. These female dogs belonged to breeds that were overrepresented compared with the general hospital population.9 Sporadic cases of acquired inguinal hernias in cats have been described, with equal occurrence in the sexes and breeds examined.51 Anatomy and Pathogenesis: The vaginal process, which contains the spermatic cord in males or the round ligament in females, passes through openings in the caudoventral abdominal wall known as inguinal rings (Figure 84-8). In both sexes, the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve, artery, and vein and the external pudendal vessels pass through the caudomedial aspect of the canal. The sagittal slit between the abdominal muscles that connects the external and internal inguinal rings is termed the inguinal canal. The internal inguinal ring is bounded medially by the rectus abdominis muscle, cranially by the caudal edge of the internal abdominal oblique muscle, and laterally and caudally by the inguinal ligament. The external inguinal ring is a longitudinal slit in the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique muscle. Close superimposition of the external and internal inguinal rings in small animals does not form a true “canal,” as its name implies, but a potential gap through which hernial disruption may occur. An “interstitial hernia” forms when a structure passes through the internal ring alone without continuing past outer wall layers. This condition is described in humans but has not been reported in small animals because of differences in anatomy of the inguinal canal (see Figure 84-8). The pathogenesis of inguinal hernias is uncertain. Few studies have proven a significant heritable influence, except in golden retrievers, cocker spaniels, and dachshunds.66 Inheritance in the last two breeds may be polygenic.98 Affected small animals should be neutered until evidence excluding heritability as a cause of this disease process is conclusive.38 Factors potentially involved in inguinal hernia formation can be grouped into three major areas: anatomic, hormonal, and metabolic. Enlargement of the entrance to the vaginal process, which, unlike that in humans, remains open, is the most important cause of inguinal hernias in domestic animals.51,125 In humans, a congenital persistent vaginal orifice is essential for development of indirect inguinal hernias.6,94 The internal abdominal oblique muscle in humans acts as a shutter to help prevent herniation of abdominal contents with abdominal contraction.125 Prevention of inguinal hernias in small animals may depend on a similar neuromuscular reflex in addition to a normal anatomic barrier at the inguinal rings.72 Bitches may be predisposed because the inguinal canal is shorter and of larger diameter than in males.33 Congenital inguinal hernias may disappear spontaneously at 12 weeks of age because of a decrease in the relative size of the inguinal rings.38 Traumatic inguinal hernias in dogs may result from a preexisting anatomic weakness in the area.83 Evidence indicates that sex hormones play an important role in the cause of inguinal hernias. In females, most inguinal hernias appear during estrus or in pregnant bitches. Acquired inguinal hernias are much less frequent in neutered females.120 Therefore, estrogen production is considered to have a close relationship to the development of inguinal hernia.98 Sex hormones may change the strength and character of the connective tissue, weakening or enlarging the inguinal rings.88 Experimentally, a sex hormone imbalance has been directly linked to formation of inguinal hernia in male and female mice.53 A multiinstitutional investigation was undertaken to examine the association between inguinal and perineal hernias in male dogs.104 Among male dogs older than 4 years with acquired, nontraumatic inguinal hernias, four of the nine dogs described in the literature and all five dogs at one institution had concurrent unilateral or bilateral perineal hernias. Most dogs did not show marked clinical problems from the perineal hernias, nor were hernias apparent to the owners. In two other studies, three of 11 and two of 16 males with nontraumatic inguinal hernias had concurrent perineal hemias.9,120 These observations may suggest a similar cause of these concurrent hernias. Weakening of the abdominal wall may result from altered nutritional or metabolic status.85 Obesity increases intraabdominal pressure, forcing abdominal fat through the inguinal canals.83 Furthermore, accumulation of fat around the round ligament may dilate the vaginal process and inguinal canal, allowing hemiation.6 Signalment and Clinical Signs: In general, inguinal hernias are more common in female dogs. In two case series, males accounted for only 8% to 11% of dogs with inguinal hernias.84,113 Of dogs with nontraumatic inguinal hernias, 37% were male.120 Males with inguinal hernias were younger than females and accounted for five of eight dogs younger than 2 years.120 Affected animals usually present with a painless, unilateral or bilateral mass with a soft, doughy consistency.9,35,58,83,112 In dogs, more unilateral inguinal hernias occur on the left side than on the right.9,29,120 The external appearance may vary, depending on the amount of vascular occlusion and the nature of the contents. Inguinal hernias may be undetectably small. Large hernias may contain a gravid uterus (hysterocele), bladder, or jejunum (Figure 84-9). Large inguinal hernias in bitches that extend caudally following the round ligament to the vulva may resemble a pendulous perineal hemia.38,83 Direct inguinal hernias in male dogs may be confused with scrotal hernias because of venous or lymphatic obstruction at the inguinal ring and subsequent swelling and edema of the testicle and spermatic cord. Diagnosis: Diagnosis is usually based on historic findings and physical examination. Vomiting, abdominal pain, and depression suggest obstructed intestine. In one report of dogs with inguinal hernias, vomiting for 2 to 6 days predicted a strangulated small intestine. In that study, all dogs with entrapped, nonviable small intestines vomited, but none of the dogs with inguinal hernias containing viable small intestine vomited.120 History of an inguinal mass and previous vaginal bleeding or discharge may indicate uterine involvement. History is usually not helpful for diagnosis of hernias when omentum or fat alone protrudes through the inguinal canals. The risk of strangulated intestine in dogs with long-standing inguinal hernia is less than 5%.120 Incarcerated hernias present more of a diagnostic challenge because palpation may not yield a diagnosis. All inguinal masses, including mammary tumors and cysts, lipomas, enlarged lymph nodes, abscesses, and hematomas, must be considered as differential diagnoses. Although immediate surgical exploration facilitates diagnosis of an inguinal mass or hernia, surgical correction of such disorders should proceed with greater precision if the anatomic aspects are delineated first. The nature of herniated contents can be confirmed with plain or contrast radiography or computed tomography (CT). During image evaluation, particular attention is paid to the caudal abdominal wall structure (“abdominal strip”) and the fascial detail of the flank musculature; loss of definition in these areas suggests herniation.7 Contents of inguinal hernias may include omentum, fat, ovary, uterus, small intestine, colon, bladder, or spleen.4,7,9 A herniated gravid uterus is easily detected on plain radiographs by the appearance of the fetal skeleton after 43 days of gestation or, before skeletal ossification, as a lobulated fluid density.7 The bladder can be identified by taking plain radiographs before and after emptying the bladder by catheterization or with positive or negative contrast cystography. In children with inguinal hernias, pneumoperitoneography has been used to detect occult hernias on the contralateral side.48 Fine needle aspiration may help differentiate an inguinal mass from an incarcerated hernia but is rarely used because accidental puncture of a loop of intestine or pyometra could cause leakage and gross contamination. Surgical Repair: Inguinal hernias are generally best repaired at the time of diagnosis; delay may result in more difficulty in performing the operation and may increase the risk of complications. Successful surgical repair of inguinal hernias depends on knowledge of regional anatomy and appropriate surgical technique, which includes apposition of strong tissues without tension and high hernial sac ligation. Uncomplicated unilateral inguinal hernias are approached over the inguinal rings. In more complicated hernias (incarcerated or strangulated contents, concurrent serious intraabdominal trauma), the approach is first through the ventral midline for exploration; hernia repair is subsequently performed extraabdominally. Some surgeons repair inguinal hernia through the abdominal cavity.9 With this approach, sutures are placed through the parietal peritoneum, the aponeurosis of the transversalis muscle, and the rectus abdominis and internal abdominal oblique muscles.9 Laparoscopic repair of inguinal hernia in affected beagle dogs by direct sac ligation or prosthesis onlay has been described in an endosurgery text.116 The conventional surgical approach to inguinal hernias begins with an incision over the lateral aspect of the swelling parallel to the flank fold.58,61,83,112 The hernial sac is exposed through blunt dissection, and the sac and contents are milked or grasped and twisted to gently push the contents through the canal. If the hernia is not easily reducible, the sac is opened (Figure 84-10), and the canal is enlarged by incising through the inguinal ring in a craniomedial direction. The neck of the hernial sac is ligated as close to the internal inguinal ring as possible, and the sac is amputated. The enlarged external inguinal ring and any incisions in the abdominal wall are closed with prolonged absorbable or nonabsorbable sutures. In traumatic inguinal hernias or when the external inguinal ring is weak, sutures can be placed between the inguinal ligament, external rectus fascia, and internal oblique abdominal muscle to aid in hernia closure. A midline approach may be preferred over the conventional approach for several reasons (Figure 84-11).83,89,124,125 This approach avoids incising through mammary tissue, an advantage especially in a lactating animal. It also permits exploration of both inguinal rings, which is recommended by the author because small hernias are frequently missed on palpation.83,89,125 In some animals, mammary tissue must be dissected directly off the external rectus fascia bilaterally to adequately expose the inguinal regions through a midline approach. A single midline incision permits simultaneous hernia repair of uncomplicated bilateral hernias and access to the abdominal cavity for complicated hernias. Additionally, it is necessary for ovariohysterectomy, which is the simplest option for treatment of a herniated gravid uterus. Successful primary repair of the hernia and replacement of the incarcerated uterus can be performed up to the seventh week of gestation if a valuable litter is expected. After 7 weeks, an ovariohysterectomy or hysterotomy may be recommended before primary hernia repair, depending on the health of the bitch and its value.98 In most animals, inguinal hernias can be repaired with the patient’s own tissues. Patients with large traumatic defects or recurrent inguinal hernias may require reinforcement of the primary hernia repair with prosthetic materials. Inguinal hernias in three intact, small female dogs were successfully repaired by an onlay polyethylene mesh technique.20 A cranial sartorius muscle flap (see Reconstruction of Large Abdominal Hernia section) has been suggested for reconstruction of large inguinal hernias when primary repair is not possible.121 A sartorius muscle flap was used in conjunction with synthetic implants to repair large chronic caudal abdominal hernias in two young cats.114 Complications, Aftercare, and Prognosis: The most common complication after inguinal hernia repair is hematoma or seroma formation from inadequate hemostasis, extensive tissue dissection during herniorrhaphy, or excessive activity after surgery. Patients are frequently reluctant to walk for several days after surgery, presumably because stretching and motion on the repair cause inflammation and pain. Swelling and tenderness in the inguinal area may also be associated with incorporation of nerves and vessels in the hernia repair or ensuing infection. If suppuration occurs, the skin and subcutaneous layers are opened, and local treatment measures are undertaken. Early recognition and treatment of infection reduce the risk of hernia dehiscence.109 In a large series of inguinal hernia repairs in dogs, the overall prevalence of postoperative complications was 17%, and the mortality rate was 3%. Incisional infection, peritonitis and sepsis, and hernia recurrence were responsible for most postoperative complications. One dog died of intestinal dehiscence after resection of an entrapped, nonviable intestinal segment within the hernia.120 Perioperative antibiotics and postoperative bandages are generally not necessary in uncomplicated hernias. If excessive dead space is anticipated, especially after trauma, dressings with or without placement of a closed drain may help prevent seroma formation. Exercise is strictly limited until suture removal. Controlled leash walking soon after surgery is encouraged to decrease postoperative edema. The incision is monitored for swelling or discharge, and skin sutures are removed in 10 to 14 days. Prognosis for uncomplicated repair of inguinal hernia is good to excellent. In one study, all but one of 61 dogs with inguinal hernias survived.9 Scrotal hernias are indirect hernias that result from a defect in the vaginal ring, allowing abdominal contents to protrude into the vaginal process alongside spermatic cord contents (see Figure 84-7).78 Herniated organs within the vaginal process do not necessarily have to extend as far distally as the scrotum for the condition to be considered a scrotal hernia. These hernias are rare, particularly in cats.35,67,76 Most case reports involve young male dogs.* Dog breeds with scrotal hernias are generally larger than breeds of female dogs with inguinal hemias.9 Strangulation of contents occurs more frequently in male dogs with scrotal hernias than in females with indirect inguinal hernias.98,120 In a study of 35 dogs with inguinal hernias, five had strangulated bowel, and four were young male dogs.120 Literature regarding the pathogenesis of scrotal hernias is limited. Unlike the situation in humans, heritability of this disorder in dogs and cats remains unknown. A congenital anatomic defect or weakness may be present in the vaginal orifice in dogs with scrotal hemias.125 Occasionally, scrotal hernia formation is associated with trauma.25 Ectopic testes have been reported in 19% to 33% of male dogs with inguinal hemias.113,120 An increased risk for inguinal hernias was found in dogs with cryptorchidism.90 Presenting signs of scrotal herniation result from protrusion of abdominal contents through the vaginal process, causing pain, swelling, and frequently organ dysfunction. Scrotal hernia is predominantly unilateral, with equal occurrence on both sides, although several bilateral cases have been reported.9,25,33,47 In humans, 15% of patients with unilateral scrotal hernia eventually developed a contralateral hernia; therefore, it would seem prudent to consider inspecting the contralateral inguinal ring in animals with unilateral scrotal hernia.96 The reported contents of scrotal hernias include periprostatic fat, omentum, and intestine.47,58 The external appearance of scrotal hernia depends on the sac contents and amount of vascular obstruction at the hernial ring. Swelling is generally cordlike, extending from the inguinal ring to the caudal aspect of the scrotum (Figure 84-12).67 Strangulated hernias have a dark discoloration of the tissues within the hernia, which is often visible externally. Signs of sharp pain are commonly exhibited during palpation of the hernia.

Abdominal Wall Reconstruction and Hernias

Definitions and Hernia Components

Anatomy of the Abdominal Wall

Location of Abdominal Hernias

Pathophysiology of Abdominal Hernias

Space-Occupying Effects

Incarceration

Strangulation

Surgical Conditions

Anatomy, Etiology, and Pathogenesis

Caudal Abdominal Hernias

Inguinal Hernias

Scrotal Hernia

Clinical Signs

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Abdominal Wall Reconstruction and Hernias

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue