Chapter 6 Abdominal Pain

Pathophysiology and Mechanisms

Based on its origin, pain can be divided into visceral, somatic, and neuropathic. Abdominal pain is visceral in origin. Visceral pain differs from somatic pain in several ways.1 First, visceral pain is not evoked in all visceral organs because peripheral receptors behave differently. Hepatic and renal parenchyma, for example, are not sensitive to pain; therefore activation of their receptors does not reach the level of consciousness. Second, visceral pain is not always associated with injury. Stimuli producing pain include distention, ischemia, and inflammation. Third, visceral pain is diffuse and poorly localized because there are fewer sensory visceral afferent fibers relative to afferent innervations of somatic tissues. Moreover, these visceral afferent fibers terminate diffusely in the spinal cord on neurons receiving input from both somatic and visceral receptors. Fourth, visceral pain is referred to the body wall because somatic (e.g., skin and muscle) and visceral afferents terminate on the same dorsal horn neurons in the spinal cord. This viscera–somatic convergence may give rise to referred pain in areas remote from the original lesion. Fifth, visceral pain is accompanied by motor and automatic reflexes such as nausea and vomiting. Visceral afferents travel together with afferents of the autonomic nervous system, and crosstalk occurs between nerves at local and central levels.1 Thus sensory stimulation of the chemoreceptor trigger zone may initiate nausea and vomiting in addition to abdominal pain. Intense or long-lasting pain stimuli or inflammation can lead to plastic changes in the nervous system both in the periphery and at the spinal and supraspinal level. This results in enhanced visceral input, increased central neuronal activity and excitability, referred to as sensitization, and may ultimately lead to central plasticity, hyperexcitability, and pain memory.1

The visceral pain system consists of afferent peripheral fibers that synapse in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord and transmit information to a second order neuron, which than transmits information to the brain where information is further distributed to different supraspinal centers for processing.1 Visceral afferent fibers are thinly myelinated Aδ-fibers or unmyelinated C-fibers with free nerve endings that respond to mechanical, thermal, and chemical stimulation. Visceral afferents converge with neurons in the dorsal root that receive input from superficial and deep somatic tissue as well as other viscera. Thus a group of neurons become hyperexcitable in an area of the dorsal horn as a result of a visceral pain signal. This is perceived as pain in somatic tissues innervated by afferents projecting to this same area in the dorsal horn. Afferent signals in second order neurons travel in spinothalamic tracts to reach thalamus and cortex. These neurons are subject to descending control from higher brain centers, which can be inhibitory or excitatory. Descending inhibition, via endogenous opioid release on afferent fibers in the spinal cord, appears to be the major way by which brain controls pain perception. The brain can also undergo cortical reorganization by enlarging and involving neighboring areas. Central sensitization results in allodynia (i.e., pain caused by a visceral stimulus that does not normally provoke pain), hyperalgesia (i.e., decreased pain threshold), and a significant increase in the size of the referred pain area together with hyperalgesia of muscle and skin.1

Differential Diagnosis

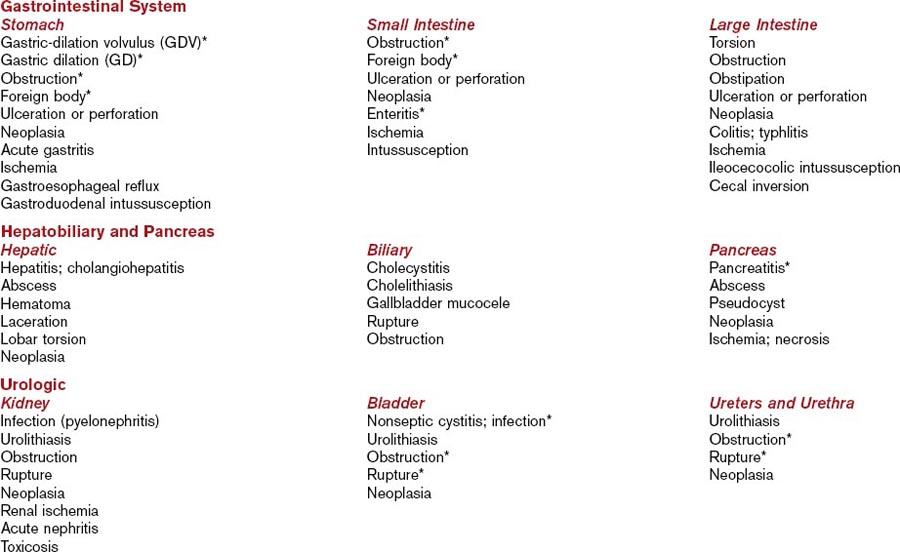

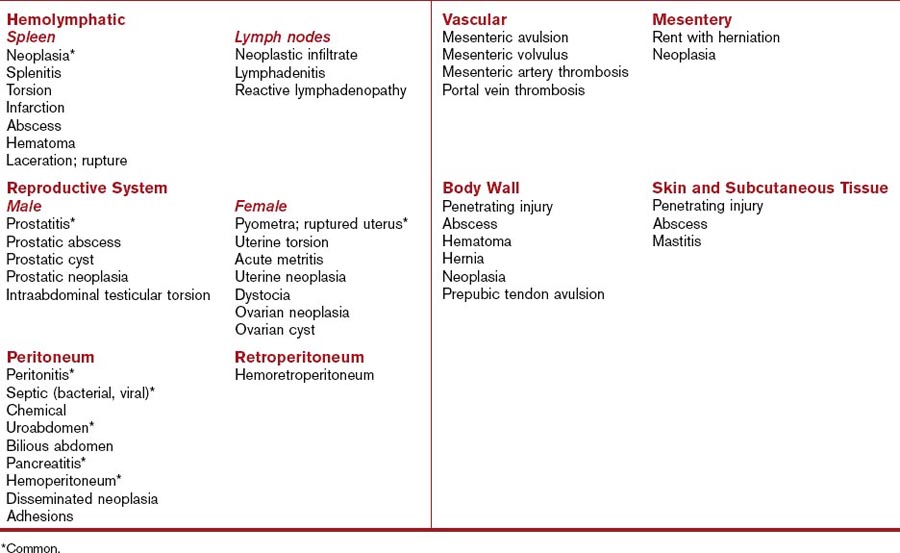

Abdominal pain is associated with a number of disorders (Table 6-1).2,3 Differential diagnoses can be categorized based on disorders of body systems. These include disorders of the gastrointestinal system (stomach, small intestine, and large intestine), hepatobiliary system and pancreas, urologic system (renal, ureter, bladder, and urethra), hemolymphatic (spleen and lymph nodes), reproductive systems (prostate and testicles; uterus and ovaries), peritoneum and retroperitoneum, vascular and mesentery, and body wall including skin and subcutaneous tissues.

Extraabdominal disorders should also be considered because they may be mistakenly interpreted as causing abdominal pain. Skeletal or thoracolumbar pain from intervertebral disk disease, diskospondylitis, spinal neoplasia, sublumbar or retroperitoneal abscesses, fractures, and pelvic trauma can mimic abdominal pain. Other extraabdominal sources of pain include meningitis, polymyositis, steatitis, heavy metal toxicities, and black widow or brown recluse spider envenomation.4 Poor abdominal palpation technique in a normal dog or cat also can elicit abdominal rigidity that may be erroneously interpreted as abdominal pain.

Evaluation of the Patient

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree