Chapter 17 Cystoscopy

Cystoscopy Introduction: Indications, Instrumentation, Techniques, and Complications

Cystoscopy is a minimally invasive diagnostic and treatment tool for the urogenital system (Boxes 17-1 and 17-2). Cystoscopy was initially used for research in the dog in 1930.1 Diagnostic cystoscopy in female dogs was not described for another 50 years.2–4 Transurethral cystoscopy in male dogs soon followed,3–4 and clinical use in cats was not reported until 1986.5 Unfortunately, cystoscopy was slowly accepted and practiced in veterinary urology. The past decade has seen much wider application. The benefits and efficiency of cystoscopy make it a practical tool for general practice and a required tool for specialty practices. Please visit the companion website for a model for patient discharge instructions.

www.tamssmallanimalendoscopy.com

Cystoscopy has become the treatment tool for calculi removal,6 ectopic ureters,7,8 polyps,9 lithotripsy,10 and transitional cell carcinoma. After the diagnostic procedures of survey radiography and ultrasonography, diagnostic cystoscopy is more efficient, increases diagnostic accuracy, provides the ability to selectively obtain biopsy specimens, and is easier to apply in clinical practice than contrast procedures and computed tomography (CT). Survey radiographs and ultrasonograms are useful in detecting calculi and enlargement, rupture, and displacement of the urinary system. Cystoscopy does require general anesthesia but otherwise is essential and efficient when managing urinary problems. Images are in color, and both images and movies can be recorded. Images are particularly useful for monitoring disease progression and regression. As compared with cystoscopy, contrast procedures require more time, are messy, are two-dimensional, and are restricted to black and white images.

Indications for Cystoscopy

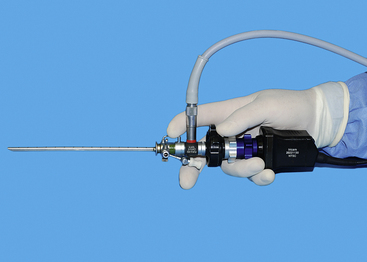

Indications for cystoscopy include chronic or recurrent urinary tract infections, hematuria, dysuria, stranguria, pollakiuria, trauma, calculi, incontinence, abnormal morphologic findings in the urine sediment, and abnormal imaging findings on abdominal radiographs and ultrasounds (see Box 17-1).11,12 Transurethral cystoscopy with a rigid cystoscope is the preferred approach for female dogs and cats (Figures 17-1 through 17-6). The urethra and bladder of male dogs can be studied with a flexible urethroscope passed through the urethra (see Figure 17-4). A small diameter semirigid scope can be used in male cats, unless they have had an urethrostomy (Figure 17-7). Routine practice after perineal urethrostomy in the cat is to examine the urinary system with a 1.9-mm rigid cystoscope. Most small animal patients can also be examined with a laparoscopic-assisted cystoscopy.6 Laparotomy for removal of calculi from the renal pelvis and ureter is facilitated by the use of small arthroscopes or cystoscopes (Figure 17-8). When the attempt is made to diagnose urinary problems, cystoscopy should be considered essential. For the previously mentioned problems, other diagnostic procedures include a history, physical examination, complete blood count, serum chemistry profile, and urinalysis. If the problem is assumed to be difficult to either diagnose or resolve, cystoscopy is a quick and direct approach for diagnosis.11 In addition, when cystoscopy is used for diagnosis, the operating channel provides an option for passing graspers, basket catheters, injection needles, scissors, and energy devices for treatments (see Box 17-2 and Figure 17-6). The only significant concern is the need for general anesthesia. Because the procedure is typically quick and minimally invasive, anesthesia is usually easily justified.

Figure 17-2 Standard sheaths for cystoscopy for use with endoscopes (see Figure 17-1). Each has an inflow and outflow port, as well as an operating port for instruments. The sheath for the 1.9-mm scope is a 10F size with a 3.5F operating channel, which will accommodate a 400-μm diode laser fiber; the sheath for the 2.7-mm scope is a 14.5F size with a 5F operating channel, which will accommodate a 800-μm fiber, and sheaths for the 3.5- to 4-mm scopes range from 17F to 24F.

(Photograph by Chris Herron © 2010 University of Georgia Research Foundation, Inc.)

Figure 17-3 Specialized sheaths for cystoscopy can be used with the 3.5- to 4-mm telescopes. These include a deflecting bridge for selective ureteral catheterization. Injection augmentation (A) and transcervical insemination (B) (see Chapter 18). During injection augmentation performed by a right-handed operator, the cystoscope is held in the left hand and a syringe attached to the needle is slowly injected with the right hand.

(Photograph by Chris Herron © 2010 University of Georgia Research Foundation, Inc.)

Figure 17-7 A 1-mm semirigid telescope with 0-degree viewing.

(From McCarthy TC, Veterinary endoscopy for the small animal practitioner, ed 1, St Louis, 2004, Saunders.)

Dysuria and Stranguria

Dysuria and stranguria are difficult urination or straining to urinate. Despite repeated attempts to void, the patient produces a typically small volume of urine. Dysuria is caused by obstructions, inflammation, or irritation. The most common cause of inflammation and a frequent cause of straining are urinary tract infections. Obstructive dysuria is most commonly produced by calculi (discussed later in this chapter) or tumors of the urethra or bladder outflow tract (Figure 17-9). Other causes of obstructive dysuria are prostatic abscesses or cysts, granulomatous masses, strictures (Figure 17-10), trauma, fibrotic bands of tissue (Figure 17-11), and urethral contraction due to bladder–urethral sphincter reflex dyssynergia. Masses obstructing the bladder outflow area can also include inflammatory polyps and blood clots.

Straining can be produced by vaginal and vestibular masses (Figure 17-12), but these masses seldom produce complete urinary obstruction.

Cystoscopy can diagnose the cause of urinary obstructive disease and has the potential to provide treatment in many patients. In female dogs, cystoscopy can be used to diagnose calculi or cancer, specifically transitional cell carcinoma (see Figure 17-9), as the cause of obstructive dysuria.13,14 Other causes include strictures (see Figure 17-10), other anatomic abnormalities, and extraluminal masses. Patients with urinary tract inflammation will not have obstructions but will have signs of inflammation. Calculi can be diagnosed in female cats by rigid cystoscopy and in male dogs by flexible urethroscopy. Transurethral cystoscopy is the preferred calculi removal treatment in female dogs when the calculi are only two to three times the diameter of the largest cystoscope appropriate for the patient. A three- or four-wire basket catheter is passed through the cystoscope’s operating channel. Urethral calculi in male dogs can sometimes be removed with the use of a basket catheter and flexible urethroscope. Calculi in male cats may be removed by transurethral cystoscopy when a perineal urethrostomy has also been performed as a part of the case management. Cystic calculi and most urethral calculi can be removed by a laparoscopic-assisted cystoscopy in both male and female dogs and cats.

Endoscopic surgical treatment can also be done for strictures, intraluminal masses, intraluminal foreign bodies, and transitional cell carcinoma. Foreign bodies may be removed by wire baskets and grasping forceps passed through the operating channel. Strictures may be resected and transitional cell carcinoma debulked with a diode laser (Figure 17-13), or both may be treated by stenting. See the “Minimally Invasive Options for Urinary Obstructions, Including Calculi” section. Although both techniques are new, preliminary clinical experience with urethral stents and laser resection of transitional cell carcinoma has demonstrated prolongation of quality of life. Some masses can be resected by traditional surgery.

Recurrent Urinary Tract Infection and Inflammation

Recurrent infections may produce a range of signs from mild straining to frequent urination. Many dogs attempt to void repeatedly, frequently delivering small amounts of urine. These repeated attempts to void should be contrasted with the traditional male marking activity. After the diagnostic studies already described, cystoscopy can usually confirm urinary tract inflammation by the presence of inflammatory lymphocytic or plasmacytic foci (Figure 17-14). Dogs with recessed or “hooded” vulvas frequently have local pyoderma and ascending infection. Inflammatory foci are commonly found in the vestibule, and these foci can spread up the urethra and into the bladder. Cystoscopy is frequently combined with episioplasty to remove the excessive perivulvar skinfold.

Urinary Incontinence

Urinary incontinence in spayed female dogs develops in as many as one in five.15–18 Many clients have accepted some degree of incontinence in older spayed female dogs and may not comment on this dribbling unless specifically asked. Fortunately, two thirds to three quarters of these dogs respond satisfactorily to either phenylpropanolamine (PPA) (1.5 mg/kg given three times a day) or estrogen.16 (The diethylstilbestrol [DES] dosage is approximately 0.5 mg for a small dog and 1 mg for a dog more than 25 kg.) If the dog gains urinary control during administration of DES, the dog is monitored until incontinence recurs, at which time the 4-day treatment is repeated. The dosage is usually adjusted according to the response to treatment. Many incontinent dogs also have urinary tract infections. Inflammation may be the cause or result of the incontinence, and it is essential to identify and treat infections as a part of incontinence management. Cystoscopy is done to eliminate anatomic causes of incontinence. Surgical treatments of sphincter dysfunction in spayed female dogs include colposuspension, the placement of an artificial urethral sphincter (hydraulic occluder), and injection augmentation during cystoscopy. Both treatments improve urinary control in most dogs when PPA treatment is maintained.

The most typical cause of persistent incontinence in young female dogs is ectopic ureter (see the “Cystoscopic Diagnosis and Treatment of Ectopic Ureter Patient Indications/Contraindications” section). PPA and estrogen seldom reduce incontinence signs in these cases. Cystoscopy is the critical and accurate technique for ectopic ureter diagnosis and can also be used for treatment. Laparotomy is rarely necessary and is usually restricted to nephrectomy of end-stage hydronephrosis. The initial workup should include urinary tract evaluation, urinalysis, urine culture, survey radiography, and ultrasonography. If incontinence persists, especially if a urinary tract infection appears to have been appropriately treated, the patient should be referred for cystoscopy. Contrast studies are rarely required for diagnosis of ectopic ureters. When cystoscopy is used in the diagnosis of an ectopic ureter, a diode laser is used to resect the membrane between the urethra and ectopic ureter. Patients treated cystoscopically have better urinary control than those treated traditionally. Despite anatomic correction of ectopic ureters, additional incontinence treatment may be needed to reduce leakage. Dogs treated cystoscopically have also avoided a laparotomy. A separate section is devoted to ectopic ureter diagnosis and treatment. (See the “Cystoscopic Diagnosis and Treatment of Ectopic Ureter Patient Indications/Contraindications” section.)

Hematuria and Other Abnormal Discharges

Hematuria and purulent discharges can be produced in the urogenital system at any point from the kidney to the external genitalia. The anatomic site can sometimes be localized depending on the timing of hemorrhage with respect to urination. Blood dripping frequently or at the start of urination is usually more external, from the prostate to the tip of the urethra, prepuce, or vestibule. Blood seen throughout urination is usually from the bladder or kidneys, cranial to the urethral sphincters. The source of blood may be from trauma, neoplasia, or polyps or may be idiopathic (Figure 17-15).19 Survey radiography and ultrasonography should be done, but the most diagnostic technique is usually cystoscopy. Masses can be identified, and diagnostic samples can be obtained for histologic evaluation. Traumatic injuries are usually just verified, but catheterization until the injury heals or surgery is occasionally appropriate. Some dogs develop renal origin hematuria, and the location can be easily identified with cystoscopy (Figure 17-15).19

Instrumentation

Transurethral cystoscopy in the female dog and cat is performed with a rigid cystoscope.11,12,20 All have a 30-degree angle, which provides side viewing as well as enough forward viewing to direct the scope into the urogenital system. The side viewing increases the examination capabilities because the scope can be rotated 360 degrees. Cystoscopes consist of a scope that is inserted into a sheath. Cystoscope sheaths have two fluid ports: one is for fluid infusion and the other is for outflow. Infusion of saline or a balanced electrolyte solution permits flushing and distension of an optical space. It is important to avoid overdistension of the bladder, which is drained via the outflow port. The most frequently used scope is a 2.7-mm, 18-cm-long cystoscope with a 14.5F sheath (see Figure 17-1). It can be used in female dogs as small as 5 kg. In dogs more than 15 to 20 kg, this 2.7-mm cystoscope can usually be used to examine the urethral and bladder outflow but is too short to do a thorough bladder examination. In these larger female dogs, a 3.5- or 4-mm, 30-cm-long cystoscope is preferred. In female dogs smaller than 5 kg and in female cats, a 1.9-mm, 18-cm-long cystoscope is required. Even this scope becomes difficult to use in females less than 2 kg. Because the 1.9-mm scope can be broken, it is also provided in an integrated fashion with the scope and sheath as a unit. Specialized cystoscopes can be useful, especially for injection augmentation and selective catheterization of ureters.21

Transurethral cystoscopy of male dogs is done with a flexible urethroscope. My preference is a 2.5-mm by 70- or 100-cm-long fiberoptic scope (see Figure 17-4). This scope tapers from 2.5 mm at the tip to 2.8 mm near its eyepiece. This scope can be passed up the urethra of a male dog over 10 kg and sometimes in dogs as small as 6.5 kg. It can also be passed from the bladder to the region of the os penis during laparoscopic-assisted cystoscopy in smaller dogs. The advantage of the fiberoptic scope is the ability to use the standard camera and light cable connected to either the cystoscope or the laparoscope during a laparoscopic-assisted cystoscopy. This reduces the instrumentation for examination of the bladder and urethra during this procedure as compared with use of the flexible scope, which requires a separate video endoscopy system. Male cats can be examined with a 1.2-mm-diameter flexible cystourethroscope or a semirigid 1-mm scope.12

Cystoscopic Techniques

Rigid transurethral cystoscopy is selected for female dogs and cats and for male cats after perineal urethrostomy. The ability to provide high flows quickly provides a clear optical media. The 30-degree viewing with a rigid scope provides excellent images of the entire urogenital system. Because of the long and circuitous urethra, male dogs require the use of flexible endoscopy. This provides lower infusion rates and limited ability to examine the entire bladder. Another alternative for male dogs and cats is laparoscopic-assisted cystoscopy. This technique is even used for removal of calculi from the urethra or for diagnosis of bladder and proximal urethral masses.

Transurethral Cystoscopy in Female Dogs and Cats

Multiple techniques have been used for transurethral cystoscopy, but I have developed preferences after experimentation with alternatives. The patient is placed on her back with the vulva positioned at the end of the table; the operator is behind the dog, and the monitor is at the patient’s head, opposite the cystoscopy site from the operator (see Figure 17-16, A). A modest amount of clipping is done about the vulva. This area is scrubbed in an effort to reduce contamination. A sterile drape is fenestrated for the vulva and placed over the patient to leave the vulva exposed. Sterile gloves are used (see Figure 17-16, B). Cystoscopic equipment is either sterilized or disinfected with glutaraldehyde (Cidex). These practices are done to limit contamination.

The cystoscope is advanced through the vestibule and into either the urethra or vagina with direct visualization and fluid infusion (Figures 17-17 and 17-18). Although a blunt obturator is routinely included as part of the cystoscopic package, it is not used for dogs and cats. The cystoscope is held in the dominant hand, and the light cable is in the up position. The operator should be looking down or dorsally through the 30-degree scope in the dog placed in dorsal recumbency. To examine areas on either side or ventrally, the operator should rotate the light cable and scope while maintaining the camera in the same orientation. The vulva lips are closed and an optical space is produced within the vestibule by infusion of fluid through the infusion port; this allows the urethra to be seen and entered. Fluid infusion is by gravity flow with either saline, Ringer’s solution, lactated Ringer’s solution, or some sterile isotonic electrolyte fluid (see Figure 17-17). Before either the urethra or vagina is entered, the vestibule should be examined. The urethra is entered after holding the tip of the cystoscope at the urethral orifice so that the urethra can be dilated with fluid infusion. As the cystoscope is advanced, care should be taken not to advance it forward against resistance. The dorsal wall of the urethra can be viewed, but to view the entire urethral lumen would cause the point of the cystoscope sheath to be pushed against the ventral urethral wall when a 30-degree cystoscope is advanced. The entire urethra wall can be easily examined by ventral displacement of the cystoscope’s tip during withdrawal of the cystoscope from the bladder. When the bladder is entered, residual urine is permitted to flow through the outflow port. When the outflow port is open, the inflow port should be closed. Once the bladder is collapsed, the outflow port is closed and inflow is turned on. The flushing procedure is repeated until a clear optical space permits examination of the lining of the urinary system. Care must be taken to avoid overdistension of the bladder. Overdistention can produce mucosal tears in the bladder and can cause difficulties in examining the ureters and cranial portion of the bladder. Dogs more than 20 kg are frequently examined with the 2.7-mm cystoscope because the most critical areas are from the bladder outflow to the exterior, and much of the bladder can be examined if the bladder is only mildly distended. Before or after examination of the urinary system, the vagina is entered and the cystoscope advanced as far cranially as possible. Because this procedure is normally done quickly, it is common to repeat passage of the cystoscope into the bladder so that a thorough examination is ensured. The bladder is emptied on the final examination.

Transurethral Cystoscopy in Male Dogs

The distal portion of the urethra can be examined with the use of a short, rigid scope with a sheath, such as a 1.9-mm cystoscope and various arthroscopes. For a complete urethral examination, a long (70- to 100-cm) urethral flexible scope is used. It is preferable to be able to deflect the tip in at least one direction, for example, neutral to left to right. Rotation of the flexible scope provides the ability to turn the tip in each of four directions. The approach to passing either short, rigid or longer flexible scopes is similar to passing a urethral catheter. Adequate urethral distension frequently requires injection by syringe in addition to the standard gravity infusion. As the urethroscope is being passed, avoid forcing the tip against the wall, which produces a “pink-out.” Manipulation of the urethra and bladder can be helpful while the urethroscope is advanced. This manipulation can be directly on the urethra and penis, rectal palpation of the prostatic urethra, or abdominal manipulation of the bladder. The best examination, images, and movies are obtained as the urethroscope is being withdrawn. Good viewing requires a slow, steady withdrawal with redirection of the tip to retain a luminal view. Within the bladder, a clear optical space must be obtained, which can be difficult to accomplish with the low flows through the 2.5- to 2.8-mm flexible scope. It is helpful to empty and flush the bladder with a urethral catheter before urethroscopy. Examination of the bladder is easier if it is only modestly distended. A thorough examination can be done by moving the tip back and forth and rotating the scope 90 degrees.

Laparoscopic-Assisted Cystoscopy

Calculi too large for transurethral cystoscopic removal in female dogs and cats and calculi in male dogs and cats can be removed with the use of cystoscopy done as a laparoscopic-assisted procedure (Figure 17-19).6 The rare contraindications for calculi removal by either transurethral cystoscopic or laparoscopic-assisted cystoscopic techniques are very large calculi and perhaps several dozen calculi in a dog. These calculi may be better removed by traditional cystotomy. Other calculi that would be removed by traditional laparotomy are in patients needing other major abdominal surgeries. Examples include removal of nephroliths along with a nephrectomy. Patients requiring a simple liver biopsy and calculi removal are usually better treated by laparoscopy. Laparoscopic-assisted cystoscopy has also been used to resect masses and to examine the bladder outflow tract.

Two laparoscopic trocars are used for laparoscopic-assisted cystoscopy. The monitor is placed caudal to the patient (see Figure 17-19). Laparoscopic techniques are described in the “Laparoscopic Surgery Introduction” portion of Chapter 15. The trocar for a 5-mm laparoscope is placed on the midline, approximately 3 cm caudal to the umbilicus. The abdomen is insufflated, and the site for the second trocar is selected. This trocar is for a 5-mm laparoscopic Babcock forceps to grasp and lift the cranial region of the bladder to the abdominal wall. This site is on the midline for female dogs and for some male dogs, depending on the position of the prepuce in relation to the cranial portion of the bladder. It is critical that the cranial portion of the bladder is lifted to the trocar site. The site is enlarged sufficiently to expose enough of the bladder so that the bladder can be secured to the exterior. If there is bladder lumen cranial to the trocar site, it is difficult to inspect and remove calculi from the cranial pouch of the bladder. A variety of securing techniques are used to keep the bladder firmly attached to the abdominal wall and prevent urine contamination of the peritoneal cavity. Four quadrate attachments with interrupted cruciate-placed sutures are used, which permits their long tags to be secured to drapes. Some surgeons prefer to place a temporary continuous suture between the bladder and skin. Once the bladder trocar has a secure seal with the abdominal wall, a small cystotomy is performed. A 2.7-mm cystoscope is placed into the bladder via the minicystotomy. For cats and small dogs, a 1.9-mm cystoscope is used. The bladder is lavaged in similar fashion to transurethral cystoscopy. Some clinicians prefer to have a urethral catheter as an additional infusion source. The bladder and entire urethra of female dogs and the prostatic urethra of males are examined with the rigid cystoscope. Calculi are removed with a variety of instruments, depending on the size and number of the calculi. Various alligator forceps, 5-mm Babcock forceps, and arthroscopic grasping forceps are passed parallel to the cystoscope to grasp and retrieve calculi (Figure 17-20). Another calculi removal technique is to use a wire basket catheter (see Figure 17-6, B). The entire assembly of cystoscope and forceps or basket catheter are removed with the calculi, and then the cystoscope and forceps are replaced into the bladder for the next retrieval. Once the final larger calculi are removed, some smaller ones can be flushed from the bladder with a urethral catheter flush and even surgical suction. Once the calculi are removed, the cystoscope is advanced through the urethra in females and a flexible urethroscope is advanced in the urethra in males. The 2.5- to 2.8-mm flexible urethroscope can be passed from the bladder to the os penis in most dogs and through the os penis on dogs larger than 6.5 to 10 kg. It is common to see irregularly shaped calculi such that it is possible to easily pass a urethral calculi around while not feeling resistance to the passage. Urethral strictures just proximal to the os penis from prior calculi obstruction and trauma are common. Knowledge of such strictures can justify a scrotal urethrostomy (see Figure 17-10). After calculi removal and flushing, the cystotomy is closed in a single-layer, appositional suture pattern avoiding the mucosa. The greater omentum is sutured to the bladder closure.

Figure 17-20 Calculi can be removed from the bladder and urethra by either a wire basket catheter passed through the rigid cystoscope (see Figure 17-6, B) or a grasping forceps advancing parallel to the scope. The latter can be initially challenging, but practice, especially with models, quickly increases competency. Note that the relative lengths of the scope and retrieval device should be continually monitored to ensure proper orientation. To view the technique and cases demonstrating calculi removal, visit the companion website.

www.tamssmallanimalendoscopy.com

(From Rawlings CA: Endoscopic removal of urinary calculi, Compend Cont Ed Pract Vet 31(10):476-484, 2009.)

Resection of tumors, such as inflammatory polyps, can be accomplished with laparoscopic assistance. The primary modification is to extend the trocar site enough to exteriorize the bladder. The cystoscope, or even a laparoscope, can be placed into the bladder lumen to accurately define the margins of and resect an inflammatory polyp. Laparoscopy can also be used for a lymph node biopsy to stage transitional cell carcinoma.

Intraoperative Nephroscopy and Cystoscopy

Rigid endoscopy during open (or traditional) surgery can be very useful for improving visualization and surgical results. A 2.7- or 1.9-mm cystoscope or a small arthroscope can be placed into intestinal, biliary, or urogenital systems (see Figure 17-8). As compared with traditional surgery that is even supplemented with magnifying surgical loops and diode head lights, scopes provide better lighting, magnification, photographic capability, and minimal surgical insults. The optical space is obtained as for cystoscopy with the use of saline or Ringer’s solution. If hemorrhage is profuse, air or carbon dioxide can be used.

Potential Cystoscopic Problems

Laparoscopic-assisted cystoscopy rarely causes problems; however, one problem is peritoneal contamination with urine if the bladder is not secured snugly against the abdominal wall. I have only seen this once, and it should not occur after an initial experience. I have had one case requiring conversion after penetration of the bladder wall when using a 5-mm laparoscopic biopsy cup forceps. Closure of the bladder wall defect was simple and probably could have been performed laparoscopically. I do not use the 5-mm biopsy forceps when obtaining a sample from the bladder wall. The most frequent complication, although still unusual, has been subcutaneous infections at the trocar site used to access the bladder.

1. Vermooten V. Cystoscopy in male and female dogs. J Lab Clin Med. 1930;15:650-657.

2. Cooper J.E., Milroy E.J., Turton J.A., et al. Cystoscopic examination of male and female dogs. Vet Rec. 1984;115:571-574.

3. Bearley M.J., Cooper J.E. The diagnosis of bladder disease in dogs by cystoscopy. J Small Anim Pract. 1985;28:75-85.

4. Biewenga W.J., van Oosterom R.A.A. Cystourethroscopy in the dog. Vet Q. 1985;7:229-231.

5. McCarthy T.C., McDermaid S.L. Prepubic percutaneous cystoscopy in the dog and cat. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1986;22:213-219.

6. Rawlings C.A., Barsanti J.A., Mahaffey M.B., et al. Use of laparoscopic-assisted cystoscopy for removal of calculi in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2003;222:759-761.

7. McCarthy T.C. Transurethral cystoscopy for correction of ectopic ureter. Vet Med. 2006;102:558-560.

8. Berent A.C., Mayhew P.D., Porat-Mosenco Y. Use of cystoscopic-guided laser ablation for treatment of intramural ureteral ectopia in male dogs: four cases (2006-2007). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2008;232:1026-1034.

9. Rawlings C.A. Resection of inflammatory polyps in dogs using laparoscopic-assisted cystoscopy. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2007;43:1-5.

10. Senior D.F. Electrohydraulic shock-wave lithotripsy for experimental canine struvite bladder stone disease. Vet Surg. 1988;22:213-219.

11. Senior D.F. Cystoscopy. In Tams T.R., editor: Small animal endoscopy, ed 2, St Louis: Mosby, 1999.

12. McCarthy T.C. Cystoscopy. In: McCarthy T.C., editor. Veterinary endoscopy for the small animal practitioner. St Louis: Saunders, 2005.

13. Valli V.E., Norris A., Jacobs R.M., et al. Pathology of canine bladder and urethral cancer and correlation with tumor progression and survival. J Comp Pathol. 1995;113:113-130.

14. Phillips B.S. Bladder tumors in dogs and cats. Compend Contin Educ Vet. 1999;21:540-564.

15. Holt P.E. Urinary incontinence in the bitch due to sphincter mechanism incompetence: prevalence in referred dogs and retrospective analysis of sixty cases. J Small Anim Pract. 1985;26:181-190.

16. Arnold S., Arnold P., Hubler M., et al. Urinary incontinence in spayed bitches: prevalence and breed predisposition. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd. 1989;131:259-263.

17. Holt P.E. Long-term evaluation of colposuspensions in the treatment of urinary incontinence due to incompetence of the urethral sphincter mechanism in the bitch. Vet Rec. 1990;127:537-542.

18. Rawlings C.A., Barsanti J.A., Mahaffey M.B., et al. Evaluation of colposuspension for treatment of incontinence in spayed female dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2001;219:770-775.

19. Kaufman A.C., Barsanti J.A., Selcer B.A. Benign essential hematuria in dogs. Compend Contin Educ Vet. 1994;16:1317.

20. Cannizzo K.L., McLoughlin M.A., Chew D.J., et al. Uroendoscopy, evaluation of the lower urinary tract. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2001;31:789-807.

21. Senior D.F., Newman R.C. Retrograde ureteral catheterization in female dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1986;22:831-834.

Minimally Invasive Options for Urinary Obstructions, Including Calculi

Interventional Radiology and Interventional Endoscopy of the Urinary Tract

In humans, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL), laser lithotripsy, ureteroscopy, ureteral stenting, and percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL)/ureterolithotomy (PCNUL)/cystolithotomy (PCCL) have almost eradicated the need for open surgery in the management of stone disease.1–7 Nephrolithiasis is a common problem in human patients, and treatment usually involves the use of ESWL (with or without concurrent ureteral stenting) or PCNL.8–10 The decision on the modality chosen is typically based on stone size and clinician preference. Ureterolithiasis is also dealt with in a similar manner. Ureteroliths less than 5 mm have been shown to pass spontaneously in 98% of people with no intervention other than medical management alone (i.e., alpha blockade).1–3,11,12 For stones that do not pass, ESWL has been effective for stone elimination in 50% to 81% of cases of ureteral stones, and most outcomes of success range from 50% to 67%.13–18 Ureteroscopy, on the other hand, has a near 100% success rate when the holmium:yttrium–aluminum–garnet (YAG) laser lithotrite is used.10,13–15,19 This makes ureteroscopy, combined with intracorporeal lithotripsy, the first-line therapy for large ureteral calculi in humans.5,10,13-15,19,20 In pediatric patients, similar outcomes have been seen with ESWL and ureteroscopic lithotripsy; overall stone-free rates have been 100% with the use of holmium:YAG laser lithotripsy guided by ureteroscopy and closer to 50% to 60% with ESWL alone.13,15,19,21 In humans, bladder and urethral stones are less of a problem than upper tract stones, contrary to that which is seen in veterinary patients. When stones are found in the bladder or urethra of humans, transurethral laser lithotripsy is the treatment of choice for stone extraction. PCCL is often the treatment of choice for large cystic stone burdens, where repetitive urethral passage and subsequent trauma are concerns.8,22

Because of the small size of veterinary patients and the common occurrence of urinary diseases, the use of these techniques is being investigated and commonly performed by the author. Publications of the use of these modalities in small animal patients are scarce, and more are under way.23–38 This section will discuss some additional equipment that is used for these interventional modalities that has not been previously discussed, and each area of the urinary tract will be addressed. The sections will separately expand on the current veterinary literature and procedural descriptions (Table 17-1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree