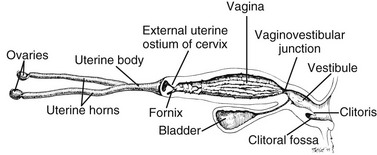

Chapter 212 In intact bitches, normal vulvar discharge originates from the uterus. It may be estral bleeding, cervical mucus during late gestation, fetal fluids at parturition, or lochia for up to 4 weeks after parturition. All other vulvar discharges in intact female dogs and all vulvar discharges in spayed females are abnormal. Pathologic uterine causes of vulvar discharges in intact and spayed bitches are summarized in Table 212-1. Involvement of the uterus must be ruled out when working up the complaint of vulvar discharge. Further insight into uterine diseases is beyond the scope of this chapter. TABLE 212-1 Pathologic Uterine Causes of Vulvar Discharges in Intact Bitches and Spayed Bitches with a Uterine Stump Vaginitis is inflammation, and commonly infection, of the mucosa cranial to the vaginovestibular junction (Figure 212-1) and is most often the symptom of an underlying problem. It often presents as purulent or mucopurulent vulvar discharge, and it must be differentiated from vestibulitis, pyometra, and other diseases that present as vulvar discharge. Direct visualization of the vaginal canal by speculum or vaginoscope helps to elucidate whether the discharge is originating from the vestibule, vagina, or cranial to the cervix. Cytologic examination and culture of a guarded swab passed cranial to the vestibule may implicate vaginal involvement. Finally, a vaginal biopsy definitively indicates the presence or absence of inflammation in the vagina. Vaginitis often is categorized into juvenile (puppy) vaginitis or adult-onset vaginitis. Figure 212-1 The canine female reproductive tract comprises ovaries, uterus, cervix, vagina, vaginovestibular junction, vestibule, vulva, and clitoris. (Used with permission from Johnston SD, Root Kustritz MV, Olson PNS: Sexual differentiation and normal anatomy of the bitch. In Johnston SD. Root Kustritz MV, Olson PNS, editors: Canine and feline theriogenology, Philadelphia, 2001, WB Saunders, p 1 [Figure 1-5A on page 6].) Juvenile vaginitis commonly is seen in bitches between 6 weeks and 1 year of age. It develops as the bitch establishes a symbiotic relationship with her endogenous bacteria and naïve vagina. Puppy vaginitis may persist for months without detrimental effects on the puppy. In fact, juvenile vaginitis usually poses greater distress to the owner than to the puppy. Cytologic evaluation of the discharge usually demonstrates mature, hypersegmented, nondegenerate neutrophils; culture often results in no significant growth (that is, either no growth or low-level, mixed populations of normal vaginal flora [Table 212-2]). TABLE 212-2 Aerobic Bacteria Isolated from the Vagina of Healthy Dogs

Vulvar Discharge

Etiology

Uterine Causes

Intact

Spayed

Subinvolution of placental site (SIPS)

Stump pyometra-ovarian remnant syndrome

Pyometra

Suture reaction (granulomatous)

Metritis

Infection (e.g., Brucella canis, enterics)

Ovarian diseases resulting in persistent estrus

Neoplasia

Uterine neoplasia

Lower Reproductive Tract Causes

Vaginitis

Juvenile (Puppy) Vaginitis.

Aeromonas

Alcaligenes faecalis

Bacillus spp.

Bacteroides spp.

Chlamydia psittaci*

Corynebacterium spp.

Clostridium perfringens*

Escherichia coli*

Enterococcus*

Enterobacter spp.*

Flavobacterium

Lactobacillus

Haemophilus spp.

Klebsiella spp.*

Micrococcus

Moraxella

Neisseria

Pasteurella spp.

Proteus spp.*

Plesiomonas

Pseudomonas spp.

Staphylococcus aureus*

Staphylococcus intermedius*

Staphylococcus pseudintermedius

Streptococcus spp. (β-hemolytic)*

Streptococcus spp. (α-hemolytic)

Streptococcus pyogenes*

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Vulvar Discharge

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue