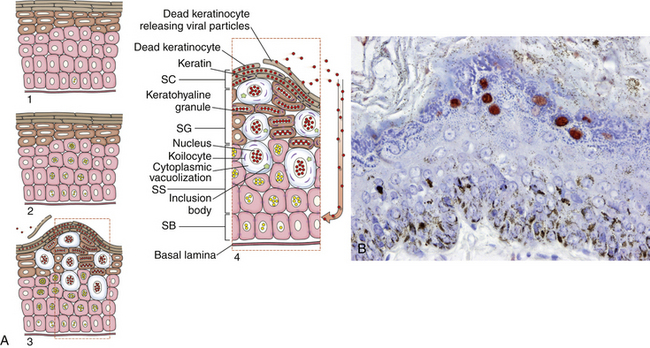

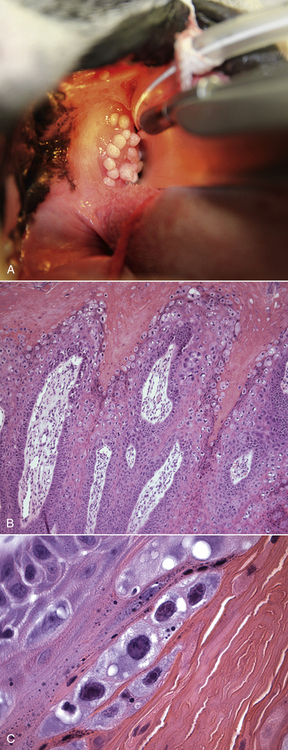

Chapter 26 Papillomaviruses cause warts, or papillomas, in a variety of animal species (Figure 26-1). They are non-enveloped, icosahedral viruses with a circular double-stranded DNA genome. Papillomaviruses have also been associated with malignant transformations within the skin and mucous membranes (Box 26-1).3 In humans, certain papillomavirus types are more likely than others to induce malignant transformation. Papillomavirus DNA has been detected using PCR assays on the skin of dogs and cats and in the oral cavity of dogs with no signs of papillomas4–6; it is not clear whether this represents subclinical infection or just carriage of papillomaviruses.7 Because of this, the association of papillomaviruses with disease in dogs and cats, especially squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs), remains somewhat unclear. Papillomaviruses are resistant in the environment and survive detergents and high temperatures. Exposure to papillomaviruses is widespread in the dog population based on serologic studies.8 Congenital or acquired deficiencies in cell-mediated immunity may predispose to papilloma formation.9–13 FIGURE 26-1 Structure of a papillomavirus. The virus is non-enveloped and has a icosahedral capsid composed of two different capsid proteins (L1 and L2). Papillomaviruses are relatively host species specific. The number of different papillomavirus types identified in dogs and cats has expanded dramatically in recent years as a result of the use of molecular techniques. Correlations appear to exist between papillomavirus types and clinical manifestations and progression of disease, although host immune status is also important. Papillomaviruses are classified on the basis of the L1 capsid protein gene sequence. At least nine types occur in dogs; an additional five novel types have been described that are not fully classified (Table 26-1).14–21 Canis familiaris papillomavirus (canine papillomavirus 1) is associated with oral papillomas and rarely with cutaneous endophytic (inverted) papillomas and invasive cutaneous SCCs.10,22,23 Other canine papillomavirus types have been associated with cutaneous inverted and exophytic papillomas, cutaneous pigmented plaques, or cutaneous in situ SCCs. Papillomavirus DNA has been detected in a few canine oral SCCs.23,24 However, most oral and cutaneous SCCs in dogs are negative for papillomavirus DNA. The eight canine papillomavirus types have been allocated to three different genera, Lambda, Tau, and Chi.7,17 Chi papillomaviruses have been associated with cutaneous plaque formation. Cocker spaniels and Kerry blue terriers may be predisposed to cutaneous papillomas, and pug dogs are predisposed to pigmented plaques. Breed predispositions to papillomavirus infections may reflect the presence of congenital defects in cell-mediated immunity; however, this is not yet proven. TABLE 26-1 Spectrum of Papillomavirus Types and Disease Associations in Dogs ∗CPV, Canine papillomavirus. Five additional types associated with cutaneous pigmented plaques exist that have not yet been definitively classified at the time of writing. (Luff JA, Affolter VK, Yeargan B, et al. Detection of six novel papillomavirus sequences in canine pigmented plaques. J Vet Diagn Invest 2012;24[3]:576-580.) Papillomavirus infections are uncommonly reported in cats when compared with dogs. They have been associated with plaque-like lesions (hereafter referred to as feline plaques), dysplastic skin lesions, multicentric Bowenoid in situ SCCs (BISC), cutaneous invasive SCCs, and feline sarcoids (also known as fibropapillomas). The complete viral genome sequence for two feline papillomaviruses types has been described, as well as several stretches of additional novel feline papillomavirus sequences. Feline sarcoids have been associated with feline sarcoid-associated papillomavirus (FeSarPV) infection, for which cattle may be a reservoir.25 Sarcoids have been described in cats from North America, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Australia, and affected cats are often young (<5 years), male, outdoor cats from rural environments. Felis domesticus papillomavirus 1 (FdPV-1) has been detected in feline viral plaques.26,27 Felis domesticus papillomavirus 2 (FdPV-2) and other papillomaviruses, including papillomaviruses with homology to human papillomaviruses, have been detected in cats with plaques, BISCs, and invasive SCCs.27–31 FdPV-2 is strongly associated with feline plaque formation.32 The finding of papillomavirus DNA with homology to the DNA of human papillomaviruses in cats suggests the possibility of transmission of papillomaviruses between humans and cats; however, additional studies are needed.30,31Although papillomavirus DNA has been detected in a feline oral SCC,33 papillomaviruses do not seem to be responsible for most oral SCCs in cats.34 Infection with papillomaviruses follows inoculation of the virus through microabrasions in the skin caused by physical trauma. Initial infection and viral amplification occurs within keratinocytes of the stratum basale.35 As basal keratinocytes undergo differentiation, early viral proteins (E proteins) are expressed and associate with regulators of the cell cycle to stimulate cell cycle progression.35 This leads to enhanced proliferation of cells in the stratum spinosum and stratum granulosum, with accumulation of infected cells and papilloma formation (Figure 26-2). With the exception of feline sarcoids, which remain as latent (or nonproductive) infections, late viral products, including the virus capsid proteins (L1 and L2), are first expressed in cells of the stratum spinosum. Papillomaviruses are nonlytic viruses, and mature virions are shed with cells that exfoliate from the stratum corneum or the nonkeratinized cells of the mucous membranes. Infected cells develop a characteristic cytopathic effect, which consists of cytoplasmic vacuolization. Tens of thousands of virus particles are produced by each infected cell. Malignant transformation occurs as a result of the effect of certain viral products (also known as oncoproteins) on host cellular signals that are responsible for regulation of the cell cycle and/or apoptosis.36 For example, some papillomavirus types produce proteins that degrade p53 and retinoblastoma protein (RB), which are important tumor suppressors.37 In human papillomavirus infections, accidental integration of the human papillomavirus (HPV) genome can occur into host cell DNA, although this does not seem to be necessary for oncogenesis.36 FIGURE 26-2 Schematic representation of the events of papillomavirus infection in the epidermis. A, (1) The primary infection occurs in a cell of the stratum basale (SB) after the virus gains entry via a microabrasion. The virus replicates and produces only early proteins, which leads to increased cellular proliferation. (2) Progeny of the initial infected cells migrate laterally and move upwards, where they accumulate in the stratum spinosum (SS) and stratum granulosum (SG). (3) Cellular differentiation ultimately occurs, and large numbers of virions are produced in association with papilloma development. Virions are shed with exfoliating keratinocytes of the stratum corneum (SC). (4) Detail from 3. B, Immunoperoxidase staining of papillomavirus antigen in a cutaneous plaque from a dog. (B courtesy of Luff J, University of California, Davis. In MacLachlan NJ, Dubovi EJ, eds. Fenner’s Veterinary Virology, 4 ed. Burlington, MA: Academic Press [Elsevier]; 2011.) Oral papillomas most commonly occur in young dogs and often regress spontaneously over a 4- to 6-week period.7 They can also occur as a result of immunosuppression, such as after treatment with cyclosporin, less commonly chronic glucocorticoid treatment, or chronic infection with Ehrlichia canis. Rarely, papillomas in the caudal oropharynx obstruct respiration (Figure 26-3). Cutaneous pigmented plaques, to which pugs and miniature schnauzers are predisposed, are generally not of clinical significance but in some situations can progress to SCCs.19,38,39 Cutaneous exophytic and endophytic papillomas usually occur as solitary masses.7 Exophytic papillomas are proliferative nodules, whereas endophytic papillomas are cup-shaped lesions with a central, keratin-filled pore (Figure 26-4). Feline plaques are flat, often pigmented lesions that resemble canine papillomas histologically. Feline sarcoids are tumors that resemble equine sarcoids. Multicentric BISCs appear as multiple, hyperpigmented plaquelike lesions. FIGURE 26-3 A, Oral papillomas in the pharyngeal region of a 5-year-old male neutered Boston terrier that was receiving chronic glucocorticoid treatment for a temporal lobe glioma. B and C, Histopathology of the lesions revealed hyperkeratosis with increased keratohyalin granules and multifocal intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies, as well as secondary bacterial infection (not shown). (Courtesy of the University of California, Davis Veterinary Dermatology and Neurology Services.) FIGURE 26-4 Inverted papilloma on the abdomen of a flat-coated retriever. (From Lange CE, Favrot C. Canine papillomaviruses. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2011;41:1183-1195.)

Viral Papillomatosis

Etiology and Epidemiology

CPV Type∗

Genus

Clinical Manifestation

1

Lambda

Oral papillomas, cutaneous endophytic papillomas, invasive SCCs

2

Tau

Cutaneous endophytic and exophytic papillomas (warts)

3

Chi

Cutaneous pigmented plaques, in situ and invasive SCCs

4, 5

Chi

Cutaneous pigmented plaques

6

Lambda

Endophytic papillomas

7

Tau

Exophytic papillomas and in situ SCC

8

Chi

Cutaneous pigmented plaques

9

Cutaneous pigmented plaques

Clinical Features

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Viral Papillomatosis

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue