Chapter 111 Viral Infections

INTRODUCTION

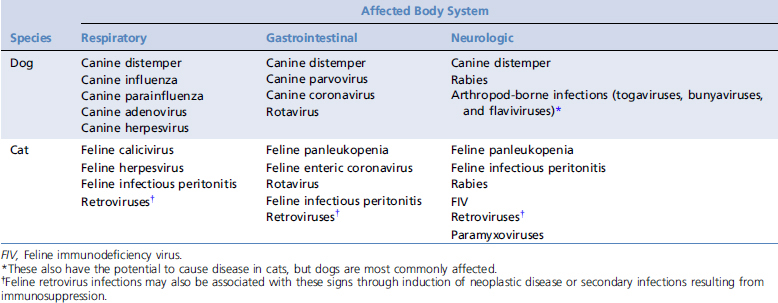

A large number of viruses may cause acute and severe illness in dogs and cats (Table 111-1). The most common or important viral infections that may come to the attention of emergency and critical care veterinarians are canine parvovirus (CPV), canine distemper virus (CDV), canine influenza virus, feline panleukopenia virus, feline herpesvirus (FHV-1), feline calicivirus (FCV), feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV), feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV), feline leukemia virus (FeLV), and rabies virus infection. The FIV and FeLV status of all cats should be determined on arrival by questioning the owner or testing using in-house enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for FeLV antigen and FIV antibody. Because these infections may be detected in asymptomatic cats, and because some cats may eliminate FeLV, positive test results alone are not reason for euthanasia. CPV infection is covered in the following chapter. Other viral diseases that may present to emergency and critical care veterinarians include enteric viral infections such as rotavirus and coronavirus infections, feline paramyxovirus infection, pseudorabies virus infection, vector-borne viral infections such as West Nile virus infection, infectious canine viral hepatitis, and canine herpesvirus infection.

Table 111-1 Viral Infections To Be Included on the List of Differential Diagnosis in Dogs and Cats With Respiratory, Gastrointestinal, or Neurologic Symptoms

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree