18 Neoplastic conditions

Neurofibroma (schwannoma, neurolemmoma, neurinoma, nerve sheath tumour/perineural fibroblastoma)

Mastocytoma (equine cutaneous mastocytosis/mast cell tumour)

Haemangioma and haemangiosarcoma

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma (extraskeletal giant cell tumour)

Cutaneous histiocytic lymphosarcoma/lymphoma

Mycosis fungoides (malignant cutaneous lymphosarcoma)

Ossifying fibroma (equine juvenile ossifying fibroma)

Sebaceous gland tumour/carcinoma

Generalized (non-epitheliotropic/multicentric) lymphosarcoma

• Congenital skin disorders (congenital melanoma, p. 229; congenital vascular hamartoma/cavernous haemangioma, p. 237)

• Viral skin disorders (equine viral papilloma, p. 135)

• Endocrine disorders (pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction/pituitary adenoma, p. 322).

Neoplastic disease is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in horses and it is certainly true that the skin is by far the most common organ affected by neoplastic disease in horses worldwide (Jackson 1936, British Equine Veterinary Association 1965, Kerr & Alden 1974, Baker & Leyland 1975, Cotchin 1977). The prevalence of skin tumours is relatively high in the horse and most tumour types have particular features which make early diagnosis important. In contrast to most other species, in equine cutaneous oncology there is little correlation between the prevalence of skin tumours and advancing age.

The pathophysiology of neoplasia centres on cells that lose their normal growth controls, replicate more rapidly and in some cases migrate locally and/or to remote sites by either haematogenous spread, lymphatic dissemination or direct contiguous invasion of adjacent structures and tissues. The underlying cause for this change in behaviour is invariably genetically driven resulting from spontaneous (innate) or induced (carcinogenic) mutations in their genetic structure, i.e. the acquisition or establishment of an oncogene (a gene that has been mutated in a way that supports neoplastic growth). The genetic alterations that culminate in cell transformation are those that control cell cycle check points, DNA repair and DNA damage recognition, apoptosis (programmed natural/planned cell death) and growth/replication signalling mechanisms. As a result of the changes the cells may lose their ‘mortality’ (planned cell death/apoptosis) although they may retain some or even all of their normal functions. The loss of normal apoptosis leads to tumour formation and the clonal expansion of the population of these cells culminates in the development of a visible tumour.

Both malignant and benign tumours have two basic components:

1. proliferating cells that are the basis of the tumour cell type

2. supportive structures including connective tissue and blood supply.

Although in most cases it is possible to differentiate between benign and malignant neoplasia morphologically, in some cases the tumour cannot be certainly categorized. It is important to realize that any particular tumour does not have to fall into one or other category; sometimes there are characteristics of both broad groups in the same mass. Also, the morphological appearance may belie the clinical behaviour of the tumour; histologically it may look benign/innocent but clinically it may behave aggressively. However, there are recognizable features that can be used in combination to try to define the tumour type more accurately (Table 18.1). These are:

Table 18.1 The basic differentiating features of benign and malignant tumours

| Benign | Malignant | |

|---|---|---|

| Extent of cell differentiation/Anaplasia | Limited/absent Well-differentiated cells (recognizably similar to normal tissue type) | Marked Lack of differentiation with anaplasia; atypical cell structure/form |

| Local invasion | Limited Usually cohesive with well-demarcated margins that do not invade local normal tissues. This does not necessarily equate with encapsulation | Extensive Locally invasive with ill-defined margins. Some are more structured and expand locally |

| Rate of growth/expansion | Slow progression Periods of rapid/slow expansion or static, and some periods of apparent regression | Rapid (or variable/slow) Erratic growth patterns |

| Mitotic index | Low Few mitotic figures and these are normal in appearance | High Numerous mitotic figures and possibly abnormal/bizarre mitoses |

| Blood supply | Variable | Variable (usually high) |

| Metastasis | No | Yes (frequently present) The more undifferentiated the tumour the more likely are metastases |

Differentiation of the cells (anaplasia)

Tumours are the result of clonal expansion and therefore the cells are usually uniform although there may be recognizable differences in their stage of maturation. The terms differentiation and anaplasia are used to describe the parenchymal cells of the tumour. Differentiation refers to the extent the cells resemble or differ from the normal cells of the tissue involved, both morphologically and functionally. The extent of cellular differentiation probably reflects the degree to which the mutation(s) alter the functions of the cell. Well-differentiated tumours are made up of cells that closely resemble the parent cell type in both morphology and function; this may make the tumour difficult to distinguish from simple hyperplasia or a hamartoma – sometimes it is only the abnormal accumulation that is recognizable. Thus, a well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma will have apparently normal keratinocytes that produce normal keratin although of course the increased cell numbers may mean that the volume of keratin is increased abnormally. This means that a simple morphological diagnosis of malignancy in a well-differentiated tumour can be very difficult. Sometimes it is reliant upon special staining and even the use of immunostaining.

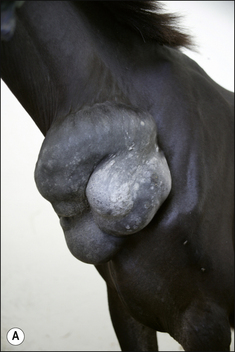

Anaplastic cells usually also vary in their structural arrangements; the tissue has a disorganized appearance with sheets or clumps of cells with a scanty vascular supply. Often, the rate of growth results in central necrosis – the tumour outgrows its own blood supply. Indeed the doubling time may be reduced if the central or larger parts of the tumour become necrotic. If all the cells survived the tumour would double its size in a predictable fashion depending on the rate of cell replication but most cells produced in a tumour do die as a consequence of pressure necrosis, ischaemia, anoxia, nutritive competition or abnormal mitosis. Also, many tumours replicate at a lower rate than the parent tissue so replication rate or even doubling time is not, on its own, always an accurate measure of the potential danger of the tumour. The absolute size of the tumour is also not a definitive indicator of its clinical significance (Fig. 18.1).

A further complication is created by the ‘precancerous’ changes that are recognizable in some tumour types. Cell dysplasia is an important aspect in the pathology of skin tumours; the term is used to describe the disorderly but non-neoplastic cell replication in which there is a loss of cell uniformity and a disruption of cell architecture with an abnormally high replication rate. In the skin this is a relatively well-recognized pathological change in the horse – mitoses and a chaotic architectural arrangement are present in all the layers of the stratified squamous epithelium. When all the layers are affected this is usually regarded as a pre-invasive neoplasm or carcinoma in situ (intra-epithelial carcinoma). Although there is evidence to suggest that the changes do in fact represent a (pre)carcinomatous change, full development of a malignancy is still not inevitable. Where the changes do not involve all the layers of the epithelium, the changes may be reversible by removal of the carcinogen or removal/sloughing of the affected cells down to a normally replicating population. Topical corticosteroids, retinoids such as tazarotene and other pro-apoptotic compounds, and simple removal of the carcinogen can still be totally curative. A good example is the precarcinomatous dysplasia that occurs on the penile and preputial skin of aged geldings (Fig. 18.2); if left, carcinoma is a regular development while if the area is cleaned of smegma and topical steroid is used, the earliest lesions are usually resolved completely.

Cell function

In general it is accepted that the more rapidly growing and the more anaplastic tumours have less (normal) functional activity. The cells of benign tumours are usually well differentiated and so they resemble their normal counterparts, both morphologically and functionally. However, in all true neoplastic disorders there is a degree of alteration of function – sometimes more and sometimes less, sometimes obvious and sometimes subtle.

The blood supply

Tumour growth is very dependent on blood supply. The blood supply to any tumour is a balance between the needs of the tumour tissue and the angiogenic capacity of the vasculature supporting it. In the absence of a dedicated blood supply, tumours may only expand to around 1–3 mm in size (Folkman 1993); once a blood supply is established, both benign and malignant tumours have a considerable ability to expand.

Angiogenesis is supported and enhanced by tumour-derived angiogenic (growth) factors expressed by proto-oncogenes, and by relative hypoxia in the expanding mass. For the most part, rapidly advancing tumours (high cell replication rates and short doubling times) will have a very high metabolic demand but this may exceed the ability of the blood vessels to invade the depths of the tumour. The blood supply to the developing tumour is initially a limitation to its growth and in many cases the central core of a rapidly expanding tumour may become necrotic – the cells outgrow their blood supply and this explains why in many cases aspiration from the centre of a tumour fails to reveal diagnostically valuable cells (see fine needle aspiration, p. 72). The total reliance of tumours on blood supply also provides a major opportunity for controlling tumour growth but adds to the difficulty of surgical management in some circumstances.

The extent of local tissue invasion

Benign tumours have a cohesive, well-defined character in general. The edges can be recognized clinically in most cases but in any case histologically the edge is well demarcated. Most malignant tumours have an ill-defined margin giving the mass a ‘bound-down’ or diffuse character. This is not necessarily an invariable indicator of malignancy, although it is an indicator of possible malignancy. For example, some forms of the nodular sarcoid are bound down either to the overlying skin (type B nodules) or to the tissues deep and lateral to the tumour mass (type A2 and type B2 sarcoids) (see p. 388). The invasion of a tumour into the surrounding and deeper tissues is thought to be a result of the alteration of cell adhesion molecules (cadherins). One of the most feared tumour properties is the ability to metastasize to remote sites. This occurs only rarely in skin tumours in horses, but where it does, it is an indicator of malignancy. Haematogenous, lymphatic and direct extensions to adjacent organs occur.

The ability to metastasize to remote sites

Although some tumours produce mediators that are directly angiogenic, the mild hypoxia that is induced by a slower-growing tumour can be enough to encourage angiogenesis into the mass. Therefore some tumours acquire large blood supplies (Fig. 18.3) and as a result become progressively more metabolically demanding; this does not necessarily equate directly with malignancy but rapidly growing tumours have a higher chance of being malignant.

Assessing tumour activity and pathological behaviour (tumour grading/staging)

Staging

This is, potentially at least, a more useful measure of the tumour’s nature than the grading system. The size of the primary lesion, the extent of spread into the adjacent tissues and local lymph node(s) and the presence of remote metastatic dissemination are incorporated into the system.

In-vitro cell culture assessment

1. Tissue collected by biopsy from a tumour can often be cultured and the cells examined closely for morphological variations and cell replication rate variations. Replication rates are quantified by measuring the rate of uptake of tritiated thymidine or 5′-bromodeoxyuridine. Of course the tests rely heavily on the availability of suitable cultural techniques for the individual cell types. Currently fibroblasts, squamous cells (keratinocytes) and vascular endothelial cells can be cultured easily but melanocytes and others are more difficult at present.

2. Monoclonal antibody technology enables similar information to be gleaned from standard formalin-fixed biopsy specimens. In these procedures antibodies directed at proliferating intracellular proteins are used to identify them. Simplistically the amount of antibody uptake is a direct indicator of the rate of replication. The tests are rapid and have been used for equine squamous cell carcinoma assessment in particular (Theon et al 1994).

Non-paraneoplastic consequences of cutaneous tumour development

1. Secretion of normal endocrine and paracrine metabolites which occurs when the neoplastic cells of a glandular or secretory structure are fully functional, i.e. well differentiated. This is not a major aspect of dermatological tumours.

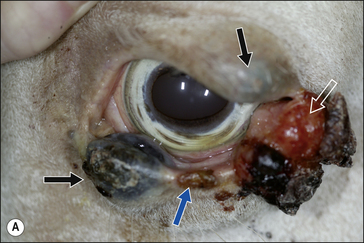

2. Functional disability when the tumour interferes with the normal function of any adjacent organ. Usually this is a result of space-occupying properties. For example, a large perineal melanoma can obstruct the rectum and result in tenesmus, obstructive constipation (obstipation) and colic as a result of non-strangulating small colon obstruction (Fig. 18.4). Although penile carcinoma is singularly rare in (working) stallions (as opposed to geldings), when it does occur it can be very aggressive with devastating effects on the animal’s breeding capacity (Fig. 18.5). The location of the tumour and its nature will clearly influence the effects it has on the adjacent structures. For example, a melanoma in the jugular groove can seriously affect the vago-sympathetic trunk and produce Horner’s syndrome and laryngeal paralysis. Even head oedema and swallowing difficulties can arise. Tumours that involve the eyelid may have serious effects on the eye itself (Fig. 18.6). This is the reason why a very careful and exhaustive clinical assessment is essential in all cases where neoplastic disease is suspected. The presenting sign may be dramatic but secondary to a less obvious tumour state. Functional loss can present in a misleading way. For example, the main (most obvious) external sign in a horse with multicentric lymphosarcoma may be diarrhoea. A careful clinical examination might identify significant cutaneous nodules. In the same way a single cutaneous haemangioma/haemangiosarcoma lesion may be missed in a horse with unilateral hind limb lameness, which could be due to disseminated tumours. It is always worth establishing the whole range of presenting signs before making a tentative diagnosis.

3. Metabolic deficiencies such as anaemia and hypoproteinaemia as a result of continued plasma and blood loss. Ulcerated and/or exposed tumours that can easily be traumatized can cause major blood and protein losses (Fig. 18.7).

4. Secondary infection/infestation: open ulcerated tumours are very liable to infection and myiasis in particular. Whilst the blood supply can be considerable it does appear that local immunity can be severely compromised by the tumour’s existence.

The paraneoplastic syndrome

Cancer should be regarded as a parasitic state but in the case of the paraneoplastic syndrome it is even more than this. It is generally considered to be a complex multi-endocrinological effect from the secretion of false endocrinologically active metabolites of the tumour. Some tumours have a much higher propensity for inducing these changes. From a clinical perspective it appears as generalized metabolic effects resulting in disproportionate weight loss, inappetence, recurrent fever and sometimes anaemia. There are few primary skin tumour types that have well-recognized paraneoplastic consequences but, for example, the common equine sarcoid can be associated with debilitating effects and with a disproportionate metabolic effect reducing performance and possibly resulting in weight loss. Furthermore there are dermatological consequences of other tumour types such as haemangiosarcoma and lymphosarcoma that are included in the paraneoplastic syndromes. Various forms of immune-mediated vasculitis including paraneoplastic pemphigus (see p. 267) and paraneoplastic pruritus are recognized (Williams et al 1995, Anhalt 1997). Often the clinical effects are most obvious in the oral mucosa but changes can occur in the skin. Histologically subepidermal clefting, and vesicle formation with accumulation of lymphocytes, plasma cells and neutrophils were reported. These changes are dependent on the tumour and so removal of a causative mass can result in resolution of the dermal problem.

The approach to a suspected skin tumour

Clinicians tend to underestimate the contribution they make in the diagnosis of neoplastic disease, often preferring to rely almost totally on the pathologist. However, if the clinician provides a really careful dossier of information for the pathologists the likelihood of an early diagnosis is far greater. The role of the pathologist is critical, if only to make a clear differentiation between abnormal accumulations of normal cells and the various stages of tumour development. Clinically, early tumours can often easily be mistaken for hyperplastic tissue responses and vice versa (Fig. 18.8). Careful review of both the clinical and pathological findings may change the diagnosis.

There is nothing special about the diagnostic approach to a cutaneous mass! The normal clinical investigative procedure should always be carried out – sometimes an aggressive looking lesion turns out to be simple and benign and possibly even not neoplastic, while another may look innocuous and actually be highly sinister. An instant diagnosis may sometimes be available through the recognition of definitive clinical features (such as melanoma) but an intuitive ‘guess’ can lead to the wrong interpretation even if the tumour is ‘recognizable’. For example, does a single, localized, darkly coloured mass on a grey horse have to be a melanoma? Where the mass is not sufficiently recognizable as to allow a definitive diagnosis to be made immediately, biopsy may be suggested. Biopsy is usually definitive provided that a suitably diagnostic specimen is obtained, because most tumour types are now recognized pathologically. The various techniques for biopsy/tissue sampling are described in Chapter 3 and typically some methods are more or less applicable to particular tumour types. However, the potential dangers of interference with any skin tumour must be considered carefully before performing any biopsy procedure. The least traumatic methods are fine needle aspiration and impression smears of ulcerated tumours. In both cases the ease and safety are somewhat offset by their variable clinical ‘return’. In many cases a reasoned judgement has to be made on the likely nature of the mass. Frozen sections examined immediately after removal may provide a rapid diagnosis, but this is often not feasible. In the case of very small tumours, a total excisional biopsy (surgical removal) may be undertaken with some degree of safety. Where biopsy is considered unavoidable, suitable therapeutic options should be available for treatment as soon as the results are known. There is no point in taking a biopsy if its results will not influence the clinical approach.

Aspects of malignancy are clearly important (even if only retrospectively). Skilled pathologists are usually able to establish whether there is an adequate margin or whether excision has not been complete. A report of a ‘safe margin of excision’ is reassuring for the surgeon. Many tumours have local variations within the mass of tissue and examination of a relatively small piece may be misleading. For example, benign granulation tissue can be interspersed amongst a fibroblastic sarcoid; there may be an area of occult sarcoid around a smaller nodular or fibroblastic sarcoid; and there may be precancerous changes surrounding a squamous cell carcinoma lesion. A limited biopsy may provide the wrong information but extensive biopsy may be undesirable. The clinical examination and the experience of the clinician are therefore important.

Table 18.2 lists common and unusual skin tumours.

Table 18.2 Common and rare skin tumours

| Common skin tumours |

| Dermal melanoma/melanosarcoma |

| Fibroma/fibrosarcoma |

| Lymphosarcoma/lymphoma |

| Mast cell tumour (mastocytoma/equine cutaneous mastocytosis) |

| Neurofibroma (schwannoma) |

| Ossifying fibroma |

| Sarcoid |

| Squamous cell carcinoma |

| Rare/unusual skin tumours |

| Basal cell carcinoma |

| Epitheliotropic lymphoma(mycosis fungoides) |

| Giant cell tumour |

| Haemangioma/haemangiosarcoma |

| Histiocytoma (malignant/fibrous) |

| Keratoma/keratoacanthoma |

| Sebaceous gland tumour |

| Sweat gland tumour |

| Trichoepithelioma |

| Lipoma/liposarcoma |

| Lymphangioma |

Diagnostic procedures for neoplasia

Important diagnostic features include the following:

• elimination of other (non-neoplastic) (nodular) disease(s) such as allergy, infection, trauma and haematoma, preferably by clinical examination

• anatomical location(s) of the tumour(s)

• number and similarity of tumours (multiple or single masses)

• status of the draining local and regional lymph nodes

• status of the surrounding tissue and any secondary effects (e.g. oedema, heat, pain, swelling)

• presence of any systemic effects suggestive of paraneoplastic syndromes, weight loss, diarrhoea, physical deformities/abnormalities, and haematological changes such as hypoglycaemia or hypercalcaemia.

Physical examination

In all cases of cutaneous neoplasia a physical examination must be undertaken. This must include:

1. A detailed, systematic clinical examination (which will often include a rectal examination, endoscopic examination of the airways, radiology and ultrasonographic investigations).

2. Specific close examination of (all) the lesion(s) to establish individual extent and character.

3. Examination of as much of the surrounding tissue as possible and the appropriate draining lymph node(s).

All three of these have a strong influence on the diagnostic process as well as on treatment and prognosis. For example, a horse with a single, slowly expanding subcutaneous mass in the medial thigh might have gross enlargement of the ipsilateral subiliac lymph node – this might support a preliminary diagnosis of lymphoma but in any case would alter the outlook considerably. Whilst an exhaustive clinical examination may seem in many cases to be an unnecessary complication, there is little worse than making a totally wrong diagnosis that seriously affects both the patient and its owner. Time spent in diagnostic processes is never wasted and there are few genuine dermatological or oncological emergencies!

Cytological examination (see Chapter 3)

The cell abnormalities encountered in aspirates are often subtle and difficult to interpret alongside artefactual alterations from sampling techniques. It is easy to over-interpret artefactual changes and indeed to overlook subtle but important diagnostic features. Incorrect sampling can easily occur and lead at best to a difficult interpretation and at worst to an error of diagnosis that could have been avoided (see p. 71). All smears/aspirates obtained from tumours must therefore be examined by an experienced cytopathologist. It is probably unacceptable to make a diagnosis without the help of such a specialist. Even recognizing ‘black’ cells in a suspect melanoma is not enough to establish useful information on pathological behaviour.

Malignant cells may be reported to exhibit some or all of the following:

Biopsy and histopathological examination (see Chapter 3)

There are several available sampling methods for use in equine oncology.

Biopsy of suspicious lesions is for the most part a sensible procedure. However, if the results of the procedure are not going to influence the management/treatment then there is little point in taking the biopsy at all. In some cases biopsy does not provide any more useful information – the common equine ‘melanoma’ probably does not warrant a biopsy because the clinical appearance is so ‘typical’. However, regular submissions even from such cases might add eventually to our understanding of the condition. Also, some tumours may be exacerbated by the process of biopsy – the equine sarcoid, for example, is probably best not subjected to biopsy unless an immediate therapeutic regimen can be applied because of the risk of exacerbation (Brostrom 1995). Therefore, presumptive diagnoses are often made and acted upon. It is only when there are complications or uncertainties that further testing is really required,

• correct collection of a representative (diagnostic) specimen

• correct processing (including fixation, section and staining)

• careful examination of the tissues by a qualified pathologist.

Haematology and serum biochemistry

These are almost invariably disappointing in skin neoplasia but may be significantly altered if:

1. There is extensive organ involvement (either primary or secondary).

2. There is significant secondary infection (either locally or systemically) as a result of impaired immune processes.

There may be significant findings if the cutaneous condition is secondary to wider neoplastic processes and when the skin changes are the result of paraneoplastic changes due to internal neoplasia. The important principle is that when haematological changes are detected, they are interpreted with care.

Equine sarcoid

Profile

There is controversy over the aetiological role of papillomaviruses. A genome which closely resembles that of the bovine papillomavirus (BPV1/BPV2) has been identified consistently in sarcoid tissue from donkeys and horses (Reid & Smith 1992), but no vegetative virus particle has yet been conclusively demonstrated. Furthermore, the genome is apparently restricted to transformed fibroblasts. Keratinocytes do not appear to be involved directly. There are several examples where species-specific papillomaviruses are closely associated with non-papillomatosis neoplastic disease in that species, e.g. human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer and bovine papillomavirus (BPV) and bladder carcinoma. Nevertheless this is possibly the only circumstance when a papillomavirus from one species has any implication for another species.

Sarcoids generally have a high capacity for local tissue invasion into the dermis and subcutis. However, true metastatic dissemination does not occur. Tumours can appear in freshly healing wounds in previously normal horses (Knottenbelt 2009), or reoccur at the same site following apparent complete surgical removal even up to 10 or more years later (Brostrom 1995).

Sarcoid is a locally aggressive, fibroblastic tumour occurring in six clinically recognizable forms (Fig. 18.9), all of which have a high propensity for recurrence (Knottenbelt & Pascoe 1994, Knottenbelt et al 1995, Knottenbelt 2005) . An individual horse may have more than one sarcoid type and for the purposes of clinical description, each lesion is classified individually. There are, however, some individual horses that have a predominant type – sometimes exclusively. Although each of these forms is commonly identifiable, it is important to recognize that the ‘less severe’ forms can rapidly progress to the more aggressive types, particularly if they are traumatized. Furthermore, the specific types may not be clearly identifiable in every case and then the’ mixed’ category is applied. It is, however, usually obvious that even the mildest forms are indeed sarcoid – in-vitro fibroblast cell cultures derived from these are typical and indistinguishable from those taken from the more aggressive lesions. These factors suggest that both cell and host factors are responsible in combination for the variety of forms.

Classification of the lesion type is important because the different types have different therapeutic demands and different prognostic implications (Fig. 18.9). What may suit a small occult lesion may not be applicable to an aggressive fibroblastic lesion. This classification is supported by pathological descriptions and is important because treatment options and prognosis vary for the different types of sarcoid. Furthermore, there is a general tendency towards progression from the milder superficial types to the more aggressive forms either as result of natural development or as a result of accidental or iatrogenic interference. The latter tends to cause a more aggressive and rapid exacerbation. The malignant form is rare but as a form of the disease it is a serious complication given that there are no effective treatments for this form and that the nature of the condition is likely to have a significant systemic and local effect on the horse. However, it is important to recognize that the sarcoid does not have defined boundaries between the various types. Usually the lesions have some aspects of other types and many progress from one type (usually occult or verrucose) to the more aggressive types (fibroblastic and malignant). There is, however, no predictable progression except to emphasize the dramatic changes that can follow interference or injury of a sarcoid.

1. Commonest (skin) tumour of horses worldwide occurring in horses of all sexes, ages, breeds and colours and in donkeys, mules and other equids. Some indications of transmissibility across the horse and between horses suggestive of infectious aetiology and (fly) vector transmission. Genetic predisposition occurs in a significant number of horses. Nevertheless, some are not affected. Familial tendencies are recognized.

2. Six different types are recognized – each with its own therapeutic limitations and prognostic differences. Sarcoids range from flat hairless areas of skin (occult sarcoid) through verrucose, nodular and fibroblastic forms. A locally malignant form occurs rarely but this does not metastasize. Each sarcoid type has its own set of differential diagnoses and can coexist, making diagnosis of each individual lesion important.

3. The variety of lesions is both a help and a hindrance to diagnosis. There is a tendency for exacerbation following biopsy (or accidental trauma or intentional surgery). Every single lesion should be individually assessed before embarking on any treatment.

4. Treatment is always likely to be difficult and recurrences and new lesions on treated cases are common. There is no consistently effective treatment (save perhaps for radiation) and each type of sarcoid warrants individual assessment andadjustment of the treatment selection. The greater the effort in selection of treatment and the more accurately it is applied, the better the result.

5. The prognosis is always guarded since all treatments have failures and exacerbations and new lesions occur regularly. Irresponsible treatment methods will invariably result in a significant worsening of the prognosis.

1. The individual lesions have a tendency to exacerbation (although this may not be invariable and it can occur over a very variable time).

2. More sarcoids are likely to develop over time and these may not necessarily be of the same type as the original lesion(s).

3. The lesions will probably require some form of treatment and that this is likely to be problematic and expensive.

4. Failure of any chosen treatment method represents a major setback and subsequent treatments are likely to be even more difficult.

5. The condition may directly affect the performance of the horse or at least there will be periods of time during treatments or during fly seasons when the horse will not be usable.

6. The likely sale value of an affected horse will be lower than it would have been had it not had any sarcoids and when the horse is sold on at a later date the sarcoids may be a significant deterrent to purchase.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

. It may also be possible to use ultrasonography to guide biopsy instruments into typical or uncomplicated locations and so improve the outcome of the procedure. Space-occupying masses, fluid-filled cavities and displacements and distortions of the normal anatomy are easily recognized with experience. Ultrasonography can also provide a surgeon with useful information about the existence and/or the extent of a surrounding capsule (Fig. CD18 • 1C)

. It may also be possible to use ultrasonography to guide biopsy instruments into typical or uncomplicated locations and so improve the outcome of the procedure. Space-occupying masses, fluid-filled cavities and displacements and distortions of the normal anatomy are easily recognized with experience. Ultrasonography can also provide a surgeon with useful information about the existence and/or the extent of a surrounding capsule (Fig. CD18 • 1C) as well as the proximity to other vital structures such as blood vessels and synovial structures (see Fig. CD18 • 21B)

as well as the proximity to other vital structures such as blood vessels and synovial structures (see Fig. CD18 • 21B) .

.

Key points: Equine sarcoid

Key points: Equine sarcoid