16 Iatrogenic and idiopathic disorders

Acquired persistent leukoderma/leukotrichia

Transient trauma-related pigmentary loss

Leukotrichia (tiger-stripe, variegated leukotrichia, reticulated leukotrichia)

Hyperaesthetic leuko(melano)trichia

Anagen defluxion and telogen effluvium

Idiopathic regional pigment-related follicular dysplasia syndrome

Idiopathic dorsal hock and palmar carpal dermatosis (‘mallenders and sallenders’)

Verrucose pastern and cannon dermatopathy (‘greasy heel’ syndrome)

There are several circumstances when iatrogenic skin disease develops.

1. Attempts to treat other diseases with topical applications or skin dressings, for example the application of ‘blisters’ or counterirritants, and firing of tendons for ‘treatment’ of orthopaedic disorders (Fig. 16.1). Application of bandages may also cause problems – especially where the dressings are non-elastic or when they are left too long or when they are not of an appropriate type (Fig. 16.1C).

2. Intentional or unintentional over-medication for skin disease. In some circumstances owners fail to read the instructions provided or feel that a ‘bit extra’ or ‘an extra application or two’ is bound to make the medication more efficacious. This is an unfortunately common event since owners often feel some degree of frustration when medications fail to improve the condition. Increasing the concentration of medications is often a dangerous approach – sometimes the skin can be significantly damaged and even permanently affected.

3. An unexpected (inappropriate) reaction to a medication or procedure whether for the skin or not; this is usually either idiosyncratic or is sometimes a result of a failure of technique. This includes such things as injection abscesses, allergic or hypersensitive reactions to applied or injected medications. It is difficult to apportion blame in circumstances when the ‘correct’ procedures and material were chosen!

4. An expected but undesirable change in the skin as a consequence of treatment applied for other purposes. Whilst some of these are temporary or transient responses others are permanent. For example, application of an antimitotic cream to a small penile squamous cell carcinoma might cause considerable transient balanoposthitis. The trade-off is of course that the tumour would resolve. A good example of a persistent change would be the changes that follow radiation exposure in the treatment of cutaneous or subcutaneous tumours such as sarcoid or lymphoma. A scar at a wound site would be an expected result of the injury but scars at the sites of the sutures might be a disappointing outcome (Fig. CD16 • 1A and B)

Vitiligo

Profile

This is an acquired depigmentation that possibly has an autoimmune basis relating to anti-melanocyte antibodies (Naughton 1986). However, the localized distribution of the condition is somewhat at odds with this theory. An auto-toxicity alternative has been proposed. Neural alterations and virus infections have also been proposed.

Depigmented spots and larger, poorly defined areas appear on the skin. They may be idiopathic or may follow primary damage to melanocytes (Meijer 1962, Pascoe 1973). They are usually restricted to horses over 4 years old. The condition may be heritable and is probably commonest in Shire and Arabian horses.

Clinical signs

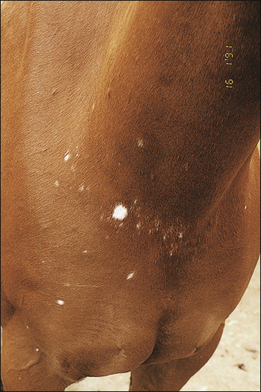

Depigmented circular or irregular spots and bigger less well-defined areas up to (or over) 1 cm diameter which increase in number rather than size (Fig. 16.2) are typical. The lesions may be more or less symmetrical in distribution.

1. An acquired depigmenting disorder of limited areas of theskin, possibly related to an autoimmune condition and frequently encountered around the eyes and face in particular.

2. Arabians, Thoroughbreds and Shire horses are possibly more prone to the condition. Grey horses may be more affectedbut this is possibly because the changes are more obvious in these. Horses of all ages can be affected. The condition is remarkably free of concurrent symptoms but some have associated hair loss.

3. Anular, more or less symmetrical, permanent, areas of depigmentation of varying extent develop without apparentsymptoms of inflammation or apparent causative insult.

4. The features are typical but biopsy can be used to confirmthe condition. There is a distinct lack of melanocytes but otherwise the skin is normal.

5. No treatment is possible although some reports suggest that copper and vitamin A are helpful.

On the body these seldom if ever cause alopecia, but around the eye where the hair coat is sparse in any case, hair loss is sometimes pronounced (Fig. 16.3). Leukoderma may or may not copy the associated leukotrichia.

Owners often become very concerned but can be reassured of the benign nature of the condition, although the progressive nature of some cases makes certain uses of the horse unrewarding. There is no associated pain, pruritus or any evidence of inflammatory responses (Figs 16.4 and 16.5 and Fig. CD16 • 3A and B) .

.

Acquired persistent leukoderma/leukotrichia

Profile

Loss of pigment in hair and skin related to various factors such as pressure injury, cryosurgery, surgery, radiation or other skin disorders. The pathological consequence is exploited in freeze marking. Even minor insults to the melanocytes cause significant loss or in some cases malfunction. This means that even minor skin damage and some trivial infections such as coital exanthema (see p. 138) can result in depigmented scars. In some disease states the melanocyte loss is less easy to explain. For example, the condition known as pinnal acanthosis (see p. 136) often causes proliferation of the epidermis with loss of pigmentation.

Key points: Acquired persistent leukoderma/leukotrichia

Key points: Acquired persistent leukoderma/leukotrichia

1. An acquired, depigmenting disorder arising from skin damage or insult. In some cases the insult may be trivial. Trauma, radiation or freeze or thermal burns are common instigating factors.

2. The distribution of the white hair (and possibly the associated white skin) changes follow the pattern of the insult. Freeze branding illustrates clearly how the melanocytes are more sensitive to insult than the skin itself.

3. Diagnosis is usually simple and the pattern of leukoderma/ leukotrichia is typically associated with other skin damage. Usually by the time the hair colour changes are detected the original insult will have disappeared. Biopsy shows evidence of scarring and loss of melanocytes.

4. Treatment is not usually possible; cosmetic dyes can be used to mask the changes. More invasive ‘treatments’ such as excision or tattoo are probably contraindicated.

5. The prognosis is excellent – it is best regarded as a cosmetic problem (unless the extent of scarring and tissue damage is limiting)

Clinical signs

Ill-defined, irregular white patches of hair and skin appear corresponding to areas of skin damage by many factors such as skin trauma (Fig. 16.6) and freeze branding (Fig. 16.7). Even tight bandages can cause melanocyte damage and white hairs appear and these are particularly obvious on distal limbs – often the owners will deny any knowledge of any episode of over-tight bandages or any obvious trauma.

Melanocytes can be destroyed by contact with irritants, harness, rubber, bits, etc. Common sites include the saddle region and withers and girth where they arise from repeated minor or more severe trauma (Fig. 16.7). The changes that follow rubber contact in particular arise without any obvious inflammatory response at all. There may be an abrupt loss of pigment in the affected skin and hair in particular and the contact area is closely related to the pattern of leukoderma/leukotrichia (Fig. 16.8 and Fig. CD16 • 4A and B) . These changes are poorly understood but alopecia is seldom encountered in these conditions.

. These changes are poorly understood but alopecia is seldom encountered in these conditions.

There is often no apparent thickening or other cutaneous changes, but with injuries and surgical sites the skin is sometimes patently scarred and thickened. It is important to realize that the hair cannot change colour overnight! The change has to appear with the growth of the hair and so it may be possible to identify roughly when the insult took place by the position of the change in the hair shafts. Often, however, the changes are fastest when the new hair coat (either summer or winter) is being produced and the old coat is being shed. This may give a misleading impression of an abrupt/acute change.

Differential diagnosis

• Vitiligo (idiopathic): no obvious instigatory event and usually round eyes/face and perineum.

• Spotted leukotrichia/leukoderma: isolated spontaneous white spots that may come and go.

• Coital exanthema: localized small and coalescent foci around genitalia only.

• Arabian fading syndrome: extensive areas of depigmentation of face and perineum.

• (Reticulated) Leukotrichia: patterned leukotrichia characteristically along the back.

• Systemic lupus erythematosus-like syndrome: multisystemic disorder.

• Discoid lupus: photo-exacerbated superficial facial disorder.

• Transient trauma-related ‘depigmentation’: history of trauma, temporary.

• Cutaneous onchocercosis: usually alopecic and thickened skin, face and neck are most often involved.

Transient trauma-related pigmentary loss

Profile

Key points: Transient trauma-related pigmentary loss

Key points: Transient trauma-related pigmentary loss

1. A common transient pigmentary loss with only occasional permanent changes.

2. Area of transient depigmentation that follows bruising, erosion or ulceration of the skin. Signs of trauma may be obvious or may be less so. Sometimes the changes can become permanent and then there may be leukoderma and leukotrichia (see p. 341) .

3. History of superficial cutaneous bruising or grazes. The transient nature of the changes differentiates this from other persistent forms of pigmentary change such as vitiligo and the changes that follow more severe skin trauma and selective destruction of melanocytes (e.g. freeze band, saddle marks).

4. Treatment is limited to nursing care of the injured skin but recovery of pigment can take some weeks.

Clinical signs

Following obvious trauma, the loss of the epidermis will inevitably result in exposure of the basal and germinal layers and possibly the dermis (Fig. 16.9). The episode of trauma is usually mild but the area involved will vary. A similar condition occurs when the skin is sunburnt or is excoriated with faeces/diarrhoea/urine or other discharges. It can also occur simply following swelling or localized inflammation with epidermal collarette formation. The pigment is gradually restored over some weeks, usually fully but sometimes to a lesser extent.

Hair loss as a result of the trauma or excoriation may occur – this is not really alopecia.

Differential diagnosis

• Vitiligo: non-painful, non-pruritic, spontaneous depigmentation around face and perineum.

• Pinky Arab syndrome: Arabian breeding and face and perineum mainly involved.

• Deep skin trauma: history of trauma.

• Radiation burns/freeze branding: known exposure.

• Reticulated leukotrichia: painful and non-painful forms restricted to patterns (‘tiger stripes’) on dorsum.

• Photosensitization: changes restricted to exposed non-pigmented skin.

• Sunburn: changes restricted to non-pigmented skin exposed to strong sunlight.

• Chemical burn/irritation: known exposure or suggestive pattern of lesions.

• Contact allergy: only the area exposed to allergen is affected.

Clipper rash

Differential diagnosis

• Urticaria: oedematous raised plaques with an acute or peracute onset and usually a rapid resolution either spontaneously or following a single injection of dexamethasone.

• Eosinophilic dermatitis with collagen necrosis: usually slower to appear and seldom resolves. Not related to clipping but could be revealed by clipping.

• Dermatophilosis: usually related more to hair loss and characteristic bacteriology.

• Staphylococcal folliculitis/furunculosis: painful and exudative localized lesions with positive cultures. Could be related to clipping trauma also.

• Chemical burn/irritation: known exposure or suggestive pattern of lesions.

• Contact allergy: only the area exposed to allergen is affected.

Leukotrichia (tiger-stripe, variegated leukotrichia, reticulated leukotrichia)

Profile

1. A rare, sporadic pigmentary disorder mainly affecting the dorsum of young (1 – 3-year-old) horses of different breeds under different conditions. ‘Brindle’ Quarterhorses may be overrepresented. Several suggestions have been made concerningits possible genetic basis and it may represent a particular form of linear keratosis; some pain initially and scaling along the lines of pigment changes are common.

2. Linear crusting lesions develop along the back with limited pain at first. Some long-term discomfort may be present. The permanent ‘tiger striping’ /brindling develops along the lines of the crusting some weeks later.

3. The underlying skin is normal histologically but the earlystages have an ill-defined oedema and pigmentary incontinence.

4. There is no treatment for the condition.

5. Suggestions that it is sufficiently heritable to exclude breeding from affected horses are ill-founded.

Clinical signs

There is a sudden development of painless small vesicles and crusts arranged in a cross-hatched pattern along the dorsum between the tail and the withers. In some cases this stage passes unnoticed. In a few cases extreme pain can be encountered with resentment to both palpation and tack/harness placement; this may then be more akin to the hyperaesthetic leukotrichia disorder (described below). Temporary alopecia follows shedding of crusts. New hair is white but the skin retains its original pigmentation (Fig. 16.10).

Figure 16.10 Reticulated leukotrichia in a Quarterhorse. Note the obvious dorsal transverse striping.

The condition has a course of about 3 months. Repeated episodes have also been reported (Yu 1997).

Differential diagnosis

• Vitiligo (idiopathic): usually around eyes, face and perineum.

• Acquired (persistent/transient) leukoderma/leukotrichia: usually trauma related).

• Spotted leukotrichia/leukoderma: isolated spontaneous white spots that may come and go.

• Coital exanthema: localized small and coalescent foci around genitalia only.

• Arabian fading syndrome: extensive areas of depigmentation of face and perineum.

• (Reticulated) leukotrichia: patterned leukotrichia characteristically along the back.

• Systemic lupus erythematosus-like syndrome: multisystemic disorder.

• Discoid lupus: photo-exacerbated superficial facial disorder.

• Transient trauma-related ‘depigmentation’: history of trauma, temporary.

• Cutaneous onchocercosis: usually alopecic and thickened skin, face and neck are most often involved.

Hyperaesthetic leuko(melano)trichia

Profile

This is a rare disease with highly characteristic signs restricted to the dorsum of mature horses and, as yet, only reported in some areas of the USA (Stannard 1987). It is possibly a variant of the reticulated leukotrichia condition (see above) but is associated with far more pain and obvious inflammation. Some cases are reported to follow the use of live or killed EHV (rhinopneumonitis/abortion) vaccine (Stannard 1987). The geographical restriction suggests that other factors are in fact involved and the vaccine relationship is likely to be coincidental/irrelevant.

Key points: Hyperaesthetic leuko(melano)trichia

Key points: Hyperaesthetic leuko(melano)trichia

1. A rare pigmentary disorder without known aetiology. Immunological changes are suspected but little is known about it. It may reflect an early or unusual form of reticulated leukotrichia in which cutaneous sensory nerve fibres are involved.

2. Multiple linear and focal, crusting, very painful lesions along the back predominately. Pain may precede the development of obvious skin lesions. The consequent pigmentary changes are persistent.

3. Biopsy is non-specific with variable evidence of perivascular superficial and deep inflammatory responses.

4. Treatment is largely symptomatic. Analgesia with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and possibly corticosteroids may help but there are too few reported cases to be definitive.

5. The condition may last up to around 3 months and may recur.

Clinical signs

Lesions remain for 1–3 months followed by spontaneous regression. Permanent white hair changes and sometimes limited alopecia are the norm (Fig. 16.11). In a few cases a similar clinical picture is seen but the skin darkens and the alopecia is more pronounced. This may or may not be a variation of the more regular but still rare hyperaesthetic leukotrichia (Fig. 16.12).

Differential diagnosis

• Dermatophilosis (Dermatophilus congolensis): usually much less painful and with characteristic paint-brush hair loss with pustular bases and a reddened area of smooth underlying skin. The organism can be identified.

• Staphylococcal furunculosis (Staphylococcus aureus/intermedius): also very painful but tends to be more diffuse and exudative. The organism can be identified in culture and smears.

• Insect bite hypersensitivity (Culicoides spp. hypersensitivity/sweet itch): usually very seasonal and not painful – pruritus is the cardinal sign in defined regions. Recurrent seasonal condition.

• Dermoid cysts (single or few, non-painful): few, well-defined, long-standing nodules.

• Reticulated leukotrichia: non-painful similar condition.

• Idiopathic and trauma-induced leukotrichia: history of trauma and changes restricted to region of skin damage.

• Photosensitization: restricted to white-skinned regions.

• Sunburn: white-skinned regions on dorsum and face primarily.

• Chemical burn/irritation: history of exposure.

• Contact allergy: recurrence – more often pruritic than painful unless secondarily infected; affected region corresponds to contact region.

Unilateral papular dermatosis

Profile

This uncommon but distinctive papular disorder with an unknown aetiology affects yearlings and 2-year-old Quarterhorses (and some Thoroughbreds); other breeds and other ages may also be affected. The aetiopathogenesis is unknown (Scott 1988a). Most lesions develop in spring/summer, suggesting an insect-related aetiology (Williams 1995) and a viral cause has been suggested also (see p. 133). The characteristic restriction of the lesions to one side of the body possibly relates to insect feeding access but the condition is not seasonal and recurrences are rarely reported.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

.

.

Key points: Vitiligo

Key points: Vitiligo

, etc. can also cause changes in the melanocytes with local development of white hair. Freeze branding, which is used as a permanent means of identification, exploits this response. Where the freeze is superficial and transient only the hair becomes white; this implies that the follicular melanocytes are perhaps the most sensitive or that the process of pigmentary uptake in hair shafts is also affected. More extensive freezing causes more damage to the melanocytes in the treated area and so the skin becomes hairless and white. Even more extensive/severe freezing results in a scar formation and this may be darker or lighter in colour than the surrounding skin.

, etc. can also cause changes in the melanocytes with local development of white hair. Freeze branding, which is used as a permanent means of identification, exploits this response. Where the freeze is superficial and transient only the hair becomes white; this implies that the follicular melanocytes are perhaps the most sensitive or that the process of pigmentary uptake in hair shafts is also affected. More extensive freezing causes more damage to the melanocytes in the treated area and so the skin becomes hairless and white. Even more extensive/severe freezing results in a scar formation and this may be darker or lighter in colour than the surrounding skin.

.

.

.

. Key points: Clipper rash

Key points: Clipper rash

but this is not established.

but this is not established. Key points: Leukotrichia

Key points: Leukotrichia