Chapter 27 Veterinary Care of Kiwi

Endemic to New Zealand, kiwi are small to medium-sized, flightless, nocturnal birds.6 They may live in native forests, scrub, or rough tussock and inhabit areas from sea level to subalpine.17 Adults will live on average 20 years in the wild but may live up to 40 years.34 Kiwi are thought to be an early offshoot from the evolutionary line of the primitive flightless ratites but appear to be more closely related to the emu than the moa.32

TAXONOMY AND GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION

Originally, three taxa were described, but recent research has now defined six species of kiwi (Table 27-1).14

Table 27-1 Common and Scientific Names and Distribution of Kiwi

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| North Island brown kiwi | Apteryx mantelli | North Island |

| Okarito brown kiwi or rowi | Apteryx rowi | Okarito district of the South Island |

| Southern tokoeka | Apteryx australis | Stewart Island |

| Haast tokoeka | Apteryx australis “Haast” | Haast district of the southern part of the South Island |

| Great spotted kiwi or roroa | Apteryx haastii | North part of the South Island |

| Little spotted kiwi | Apteryx owenii | Kapiti Island and several other offshore islands |

CONSERVATION STATUS

The range and numbers of kiwi have declined since humans arrived in New Zealand. Forest clearance has reduced available habitat and produced fragmented populations. However, the most important factor is the introduction of predators. Possums damage eggs; mustelids and feral cats kill young chicks; and dogs and ferrets may kill adults. Up to 95% of all kiwi chicks are being killed within the first 2 months of life in some areas.2

All six taxa of kiwi are threatened in the wild in New Zealand.19 The North Island brown kiwi is classified as “seriously declining,” at a rate of 5.8% per year, mainly from intense predation of young birds in the first 6 months of life.32 The Okarito brown kiwi and the Haast tokoeka are classified as “nationally critical,” and the great spotted kiwi and southern tokoeka are classified as “gradually declining.” The little spotted kiwi have an increasing population size because of their location on predator-free islands.29

Because of this wild population decline, the Kiwi Recovery Plan was launched in 1991 with the aim of “maintaining and, where possible, enhancing the current abundance, distribution and genetic diversity of Kiwi.”10,31

Operation Nest Egg was established to “head start” two kiwi taxa: the North Island brown kiwi and Okarito brown kiwi. Eggs are removed from wild kiwi nests, incubated in artificial incubators, and raised in captivity. Birds are released as subadults, usually weighing in excess of 1 kg (2.2 lb).14 At this stage they are less likely to be killed by a stoat or a cat, but released birds must still be managed, especially when they may be reached by domestic dogs and ferrets. The first release of captive-reared chicks took place in 1995 and has been highly successful.32 Ten captive institutions have been involved in this successful conservation program.

CAPTIVE STATUS

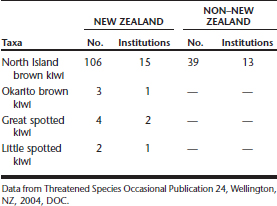

Kiwi were first held in captivity in London Zoo in 1851, but the first captive breeding did not occur until 1945.14 Currently, kiwi are more often held in New Zealand institutions, and only 13 zoos hold kiwi outside New Zealand (Table 27-3).14

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

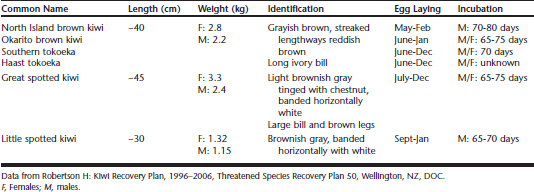

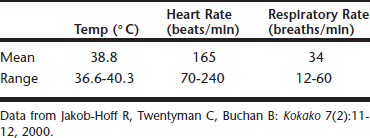

Kiwi have several unusual physical features. All taxa share the following general characteristics: small eyes but good night and day vision; large ears with a good sense of hearing; a well-developed sense of smell, the nostrils being uniquely placed at the tip of the long, sensitive bill; feathers with unlinked barbs on a single rachis that is easily shed; vestigial wings rendering them flightless; no external tail; and short, powerful legs with three forward-pointing toes equipped with sharp claws.32 Females tend to be 20% to 30% heavier and larger than males and produce one of the largest eggs in proportion to female body weight (eggs weigh about 15%-20% of female weight). Chicks hatch as miniature adults. Females also have paired functional ovaries that are thought to ovulate alternately, and males a distinct phallus that may be used for sexing. Kiwi also have a remnant of a diaphragm, and their body temperature and metabolic rate are lower than in most birds (Table 27-4).

BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION

Kiwi live in pairs, which is site specific, and they maintain and protect permanent territories. During the day they sleep in burrows, but as twilight appears, they become active and begin probing the soil and leaf litter for food with their long bill, often making snorting noises as they exhale soil. They are usually only active for the first part of the night, approximately 4 to 6 hours. Vocally most active in the first 2 hours of darkness, kiwi have sexually dimorphic calls that may transmit up to 1.5 km (0.9 mile) in ideal conditions.32 Birds tend to be most vocal in winter and spring. Juveniles are usually silent in their first year, and some nonterritorial adult or subadult birds rarely call. Birds on nests do not call.

Kiwi reproductive behavior varies between taxa.17 During courtship, a pair often remain together for hours, making loud grunts and snuffling sounds. The male and female of a pair often feed separately at night but spend about 20% of days together. Pairs are monogamous, which persists throughout the year and between years. Most eggs are laid between May/June and January, with Okarito brown kiwi laying as late as February.

North Island brown kiwi and little spotted kiwi may lay two eggs 2 to 4 weeks apart, whereas other taxa lay only one egg. The large white eggs (125 × 78 mm; 375-430 g) are laid in either a burrow or a hollow log, or sometimes under dense vegetation. Incubation is generally by the male but may be shared by the female in some taxa, and the incubation period may range from 65 to 80 days.30

ARTIFICIAL REARING

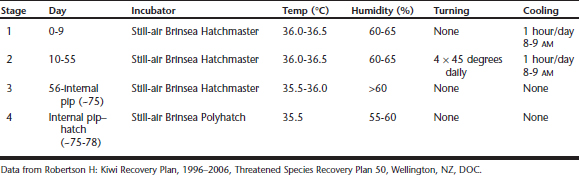

The incubation protocol is split between four age-related stages. Turning is done during days 10 to 55 in a 2-day cycle in 4 × 45–degree stages spaced evenly throughout the day. On day 1 the egg is turned 90 degrees clockwise/to the right in two stages and 90 degrees anticlockwise in two stages. (This will bring the top-center line of the egg back to 12 o’clock on the final turn.) On day 2 the egg is turned 90 degrees anticlockwise/to the left in two stages and 90 degrees clockwise in two stages. This 2-day cycle is repeated as necessary (Table 27-5).

Chicks kept too warm are usually lethargic and slow to eat. It is normal for chicks to lose 25% to 30% of their weight in the first 10 to 12 days. Force feeding should be considered if the weight loss exceeds this percentage.32 After 3 weeks, chicks should have gained their hatch weight and may be moved to an outdoor enclosure.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree