Chapter 47 Ventricular Tachyarrhythmias

INTRODUCTION

Physiologically, specialized ventricular cells, known as Purkinje fibers, may work as a pacemaker when the sinus and atrioventricular nodes fail to function appropriately, resulting in a ventricular escape rhythm or idioventricular rhythm at a rate of about 30 to 40 beats/min in dogs and 60 to 130 beats/min in cats.1,2 Three arrhythmogenic mechanisms known as enhanced automaticity, triggered activity, and reentry (Box 47-1) may affect Purkinje cells or any excitable ventricular myocyte and result in ventricular tachycardia (VT).3 They result in a ventricular rhythm faster than the physiologic idioventricular rhythm. Most human cardiologists define VT as three or more consecutive ventricular beats occurring at a rate faster than 100 beats/min, the conventional upper limit for normal sinus rhythm. In our patients, normal sinus rhythm can probably reach 150 to 180 beats/min in dogs and 220 beats/min in cats. These rates define the lower limit for VT. If a ventricular rhythm is faster than the physiologic idioventricular rhythm and slower than VT, it is called accelerated idioventricular rhythm (AIVR). The rate of an AIVR is within the range of the underlying sinus rhythm. Therefore both rhythms are seen competing on a surface electrocardiogram (ECG) because the faster pacemaker inhibits the slower one, a property known as overdrive suppression.2 Besides rate, an important feature of VT is duration, because both determine the clinical consequences of the arrhythmia. VT is described as nonsustained if it lasts less than 30 seconds and sustained if it lasts longer.

ELECTROCARDIOGRAPHIC DIAGNOSIS

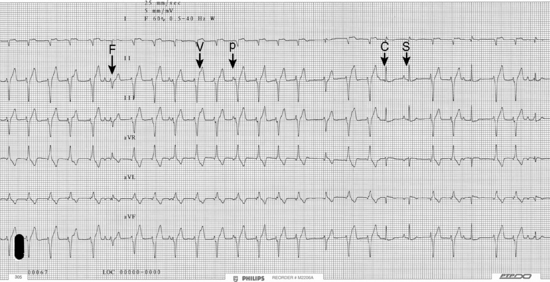

The three most reliable diagnostic criteria of VT are atrioventricular dissociation, fusion beats, and capture beats (Figure 47-1). Atrioventricular dissociation is demonstrated when P waves are occasionally seen on the ECG tracing but are not related to ventricular complexes. These P waves reflect atrial activity independently from the ventricle. On occasion apparent atrioventricular association may be seen, or ventricular beats can conduct in a retrograde fashion to the atrium in a 1:1 ratio. Therefore signs of atrioventricular association do not rule out VT. Fusion beats and capture beats are seen with paroxysmal VT and AIVR. Fusion beats result from the summation of a ventricular impulse and a simultaneous supraventricular impulse resulting in a QRS complex of intermediate morphology and preceded by a P wave (unless there is concurrent atrial fibrillation). A capture beat is a supraventricular impulse conducting through the normal conduction pathways to the ventricle during an episode of VT or AIVR. This complex occurs earlier than expected and is narrow if the conduction system is intact.4

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree