Chapter 18 Vaginoscopy and Transcervical Catheterization in the Bitch

Diagnostic vaginoscopy has traditionally been hampered by the normal anatomy of the canine vagina and is now greatly facilitated by the development of rigid cystourethroscopes with excellent optics and accessories permitting insufflation and tissue sampling for cytologic, histopathologic, and culture analysis.1 Plain radiography provides limited information about the female reproductive tract, and contrast radiography requires anesthesia and evaluates only the lumen. Ultrasonography provides good information about the reproductive tract but has limited penetration into the vagina within the pelvic canal. Sampling of the female reproductive tract via laparoscopy or laparotomy is invasive; pelvic canal anatomy again limits access.

The normal anatomy of the vagina and cervix in the bitch has also hampered transcervical access to the canine uterus until rigid cystourethroscopes were developed.1,2 Historically, intrauterine insemination required an invasive procedure (laparotomy or laparoscopy) in the bitch. In addition to its invasiveness, laparotomy requires general anesthesia, which many clinicians and clients find objectionable for an elective procedure such as artificial insemination. The laparoscopic approach to the canine uterus has been used infrequently, especially in the practice setting, similarly because of its relative invasiveness (i.e., multiple incisions and insufflation) and because it requires special equipment, expertise, and again, anesthesia. In some countries, elective surgeries such as these are not permitted.

Patient Indications

Vaginoscopy (often coupled with cystoscopy) is an important component in the diagnostic approach to vulvar and vestibulovaginal disorders associated with abnormal vulvovaginal discharge, excessive vulvar licking/excoriation, perivulvar dermatitis, dysuria, urinary incontinence, or difficulty breeding suggesting urogenital anatomic abnormalities (Figures 18-1 and 18-2).3

Cryopreservation and subsequent thawing diminish semen quality, necessitating special insemination technology. Frozen thawed semen needs to be placed close to the site of fertilization (the fallopian tube) for acceptable conception rates; intrauterine insemination is highly recommended.4 The process and resultant quality of canine cryopreservation have improved with time; however, insemination techniques remained challenging until transcervical endoscopic intrauterine access was developed. Data supporting the benefit of intrauterine deposition of frozen thawed semen exist (40% to 90% conception rates); it can then be extrapolated that better conception rates will occur with intrauterine insemination of chilled, extended, or otherwise compromised semen.5,6 Ovulation timing (e.g., vaginal cytology and serial progesterone and luteinizing hormone [LH] evaluation) best dictates the optimal day(s) for insemination, typically 3 to 6 days after the LH surge. The initial rise in the progesterone level (first day that the progesterone level is between 2 and 3 ng/mL) estimates the LH surge.

Instrumentation

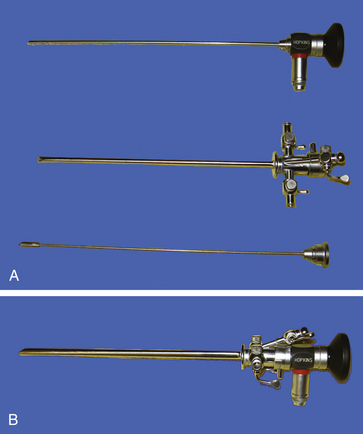

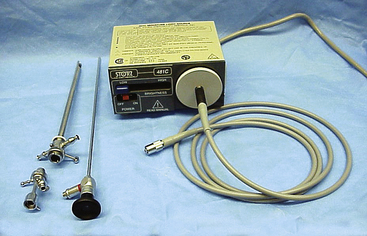

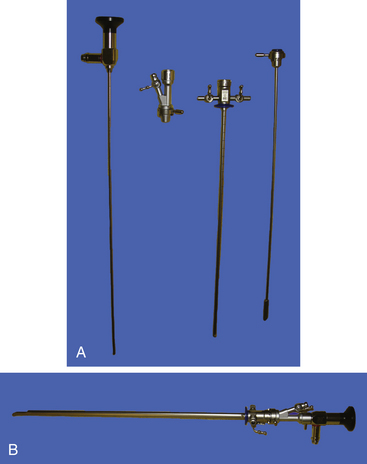

Endoscopically guided transcervical catheterization requires the use of a rigid cystourethroscope, the standard components of which are a forward oblique telescope with a 30-degree viewing angle; a protective sheath with Luer-Lok adapters and an obturator; a telescope bridge with an instrument channel; and a cold light source. The 30-degree angle is optimal for visualization of the dorsally oriented cervix. Several models and sizes of rigid cystourethroscopes are now available. The original cystourethroscope has a 3.5-mm forward oblique telescope with a 30-degree viewing angle; a 22F protective sheath with two Luer-Lok adapters and an obturator; and a telescope bridge with one 10F instrument channel. The working length of this scope is 29 cm (Hopkins Telescope, cystoscopy/reproductive sheath with obturator, bridge with instrument channel; Karl Storz, Goleta, Calif.; Figure 18-3). A smaller version (2.7-mm Multi-Purpose Rigid endoscope, 18-cm length; Karl Storz, Goleta, Calif.) accommodating a 5.5F catheter (such as is used for rhinoscopy) can be used for very small breeds (less than 4.5 kg), and a larger one (33-cm working length accommodating a 10F catheter) can be used for giant breeds (Davidson multipurpose rigid telescope, standard operating sheath, single-channel bridge; Endoscopy Support Services, Brewster, N.Y.; Figures 18-4 and 18-5). Recently, a new ureterorenoscope has been promoted for vaginoscopy and transcervical catheterization with a 6-degree viewing angle telescope and instrument sheath combined into one 8.0-13.5F unit, two Luer-Lok adaptors, a one-way instrument port with angled eyepiece, and a working length of either 34 or 43 cm. The instrument channel of the ureterorenoscope accommodates up to a 5.5F catheter or instrument (Ureterorenoscope; Karl Storz, Goleta, Calif.; Figure 18-6).

Figure 18-3 The 29-cm cystourethroscope. From left, clockwise: the bridge, sheath, telescope, and light source/cable.

Figure 18-5 A, The 33-cm cystourethroscope: (from top) obturator, sheath, bridge, and telescope. B, Assembled.

A video camera can be attached to the endoscopes, permitting enlarged imaging of the procedure. Video endoscopy is preferred because it also allows both the operator and audience (e.g., the client) to comfortably watch the entire insemination procedure. Unlike with gastrointestinal endoscopy, electronic air pumps for insufflation and suction are not generally necessary and may be hazardous to friable urogenital tissues, creating excessive distension of the vagina or bladder. Adequate air insufflation or suction can be achieved, if needed, by connecting intravenous tubing and a syringe with a three-way stopcock to one of the working channels; this arrangement is sometimes useful for insufflation for routine vaginoscopy in a nonestrual bitch and occasionally for suctioning of copious estrual fluid to improve visualization of the vaginal lumen in estrual bitches. Air distension with an insufflation bulb also works well. Irrigation with normal saline best improves visualization of the vaginal vault by distending the vaginal folds in nonestrual bitches.

Lubrication of the endoscope is seldom necessary in estrual bitches. If a lubricant is used, it should be absolutely nonspermicidal and water soluble (Priority Care nonspermicidal sterile lubricating jelly, First Priority Inc., Elgin, Ill.) and should be applied only to the midportion of the sheath. Care must be taken to avoid contact with the lens, which would obscure visibility (Table 18-1).

Table 18-1 Equipment for Endoscopic Vaginoscopy

| Equipment | Necessary | Optional |

|---|---|---|

| Rigid vaginoscope | ✓ (D,T) | |

| Light source and cable | ✓ (D,T) | |

| Video camera, screen | ✓ (D,T) | |

| Catheters (5.5-10.0F) | ✓ (D,T) | |

| Biopsy instrument | ✓ (D) | |

| Sterile guarded culturette | ✓ (D) | |

| Air insufflation bulb | ✓ (D,T) | |

| Hydraulic table | ✓ (D,T) | |

| Hydraulic chair | ✓ (D,T) |

D, Diagnostic vaginoscopy; T, transcervical insemination.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree