Chapter 12 UTERINE EDEMA IN THE MARE

Although evaluation of uterus is done by rectal palpation, a more detailed examination as well as the observation of otherwise non-palpable structures and artifacts is done ultrasonographically. Ultrasonographic evaluation of the uterus is done in order to determine pathological or physiological conditions and uterine contents.1 Because the mare is a seasonal polyestric animal, there are physiological changes that must be taken into account when examining the mare. The cervix, uterus, and ovaries change significantly between anestrus, transition, and regular cyclicity (estrus and diestrus).2

SPRING TRANSITION

In contrast to the poorly identifiable cervix of the anestrus mare, the mare in mid to late transition will have a slight increase in uterine tone and is easier to palpate per rectum. The cervix of mares that have previously had foals will be easier to palpate and identify whereas the cervix of maiden mares will not be as obvious. The cervix in late transition will be edematous in most mares, but the degree of edema will vary significantly between mares.3

The uterus of the transitional mare will be characteristic because of the presence of endometrial edema, which is characterized by the visualization of the endometrial folds giving the characteristic appearance of a “cart wheel” or “sliced orange”1,2 The hallmark of the uterus of transitional mares particularly in mid to late transition is the persistence of the endometrial edema for several days or even weeks with no significant change. In many instances a small amount of fluid accumulation in the uterus can be detected. Because the uterine folds increase in thickness, there is also a significant increase of the surface area of the uterus, and small fluid accumulations can easily dissipate within the uterus. The presence of multiple medium to large follicles 25–35 mm or larger is typical of the transitional period.2

THE CYCLING MARE

Once the mare has had the first ovulation of the year, the interovulatory interval is on the average 20–22 days. Ovulation is preceded by a follicular phase that typically lasts 5–7 days during which the mare shows behavioral estrus, and followed by a luteal phase that lasts 14–16 days and the mare is not receptive. However, unlike other domestic animals, the mare has an LH peak after ovulation and often displays strong signs of heat for up to 48 hours after ovulation has taken place. Although mares can be bred as far as 6 days prior to ovulation with acceptable pregnancy results, in order to maximize their fertility mares should be mated within 48 hours prior and up to 6 hours after ovulation.4 A single mating as many as 5 or 6 days before ovulation with a fertile stallion will often result in pregnancy, but pregnancy rates increase when mares are bred closer to ovulation.

Accurate prediction of ovulation timing becomes a critical component of breeding management in order to maximize the efficiency of a breeding operation and ultimately the pregnancy rates.5 Reducing the number of breedings or inseminations per cycle maximizes stallion or semen usage and reduces mare contamination and farm labor with the associated costs. The ideal number of covers or inseminations per cycle when a healthy mare is bred using a fertile stallion or good quality semen is one. However, well-managed breeding operations can allow up to 10% rebreeds in the same cycle. Current systems to determine the timing of breeding rely on several of the following: (1) teasing by a stallion, (2) cervical relaxation determined by rectal palpation or vaginal speculum examination, (3) the presence of a “large” follicle detected by rectal palpation and ultrasonography, (4) appearance of the follicle on ultrasound examination, (5) timing from treatment with an inducing agent, and (6) the presence and pattern uterine edema.6–8

Cervical Relaxation

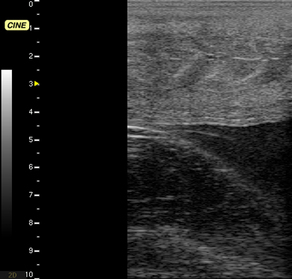

When in heat the normal mare has a relaxed cervix that drops down to the vaginal floor. The degree of relaxation depends on the age of the mare as well as her reproductive status and can be determined by rectal palpation as well as a vaginal examination through a speculum. Lack of cervical relaxation when in heat is often seen in mares with long-standing uterine infections, in older maiden mares, and in some young maiden mares that have not yet had a foal. The ultrasonographic image of the cervix is commonly observed as a fishbone appearance (Fig. 12-1).

Presence of a Large Follicle

Follicular growth in the mare is a dynamic process that does not appear to be related to the presence of progesterone and is well described in Chapter 11. As stated previously, it is not uncommon to have mares develop follicles >35 mm in diameter during diestrus. During estrus the follicular phase is characterized by the growth of follicles at about 3 mm per day until it reaches its pre-ovulatory size of 40–45 mm on the average mare but often 50–55 mm in larger breeds. Mares that are in estrus will have a dominant follicle, but not all mares with a large follicle are in heat. Inexperienced veterinarians that do not have access to a teasing stallion can often be confused by the presence of such a follicle and breed mares during diestrus because of the presence of a large follicle. Mares with diestrus follicles, regardless of size, will not respond to ovulatory-inducing agents.

Ultrasonographic Appearance of the Pre-ovulatory Follicle

The ultrasonographic appearance of the follicle as the mare approaches ovulation will vary depending on the position of the follicle within the ovary or the proximity to the ovulation fossa. Follicles that are close to the ovulation fossa will not have a significant change in shape; however, follicles that are at one of the ovarian poles will have a “pear-like” appearance and will become more flaccid at palpation and the mare will often show varying degrees of discomfort or pain when the follicle is touched. When using power Doppler ultrasonography, one can detect an increase in blood flow to the follicular wall area, as shown in Chapter 11.