Chapter 10 Urinogenital disorders

Urinary tract

Introduction

Conditions with secondary renal pathology include pruritus-pyrexia-hemorrhagica (PPH) (9.39), oak (acorn) poisoning (13.6, 13.7), renal infarction secondary to caudal vena caval thrombosis (5.33), babesiosis (redwater, 12.39–12.43), and the many causes of bacteremia and septicemia.

Pyelonephritis

Clinical features

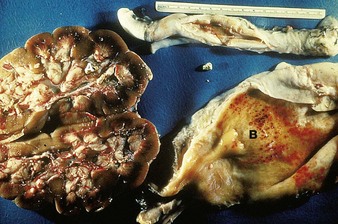

although worldwide in distribution, cases of pyelonephritis are sporadic only and overall incidence is low. Most often seen in the first 3 months postpartum, it may result from contact with infected urine or from a genital tract infection. Most infections start in the winter housing period when cow-to-cow contact increases. Affected cows are pyrexic, lose weight, show polyuria, hematuria or pyuria, and may develop a dry, brownish discoloration of the coat, often with urine staining over the tail and perineum which resembles cystitis (10.14). Rectal palpation may reveal a thickened ureter or enlarged (left) kidney. An 18-month-old Limousin heifer (10.1), ill for several days, showed at autopsy a granular renal cortex with areas of recent hemorrhage. In addition, several small discrete renal abscesses are evident, one of which has burst.

Severe chronic pyelonephritis is illustrated in 10.2 where the left kidney is contracted and pale, and the right kidney is enlarged and appears granular. Both ureters, particularly the left, are thickened as they contain pus and cellular debris (pyoureter).

In a case of chronic pyelonephritis (10.3) calculi (A) are present in the renal calyces, further calculi are in a thickened fibrotic ureter, and the bladder mucosa contains multiple petechiae (B).

Differential diagnosis

urolithiasis, intestinal obstruction (in acute pyelonephritis), cystitis (10.14).

Leptospirosis

Clinical features

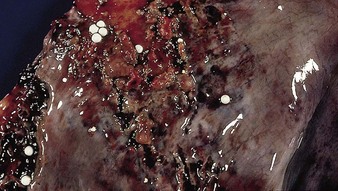

in adults the main effects of Leptospira interrogans serovar pomona or hardjo infection are multiple abortions (see 10.86 for a fetus from a possible leptospiral abortion), stillbirths, loss of milk production, and reduced fertility. In calves L. pomona causes an acute septicemia with hemoglobinuria, jaundice, anemia, and possibly death. Dark, swollen kidneys (10.4) are usually indicative of a hemolytic crisis. Recovered cattle show little more than ill-defined, grayish, cortical spots, indicative of a focal interstitial nephritis. The spirochetes may be seen under dark field microscopy of urine, but confirmation of diagnosis otherwise depends on serology or histopathology.

Differential diagnosis

babesiosis (12.39–12.43), anaplasmosis (12.44–12.47), rape and kale poisoning (13.10), postparturient hemoglobinuria, bacillary hemoglobinuria. Note the completely different appearances of the kidney in pyelonephritis (10.2) and amyloidosis (10.13).

Urolithiasis

Etiology

urolithiasis has a multifactorial etiology including dietary mineral imbalance, a relatively reduced fluid intake, high concentrate intake, and castration. The condition begins with microcalculus formation in the kidneys (10.3), and clinical problems arise when the calculi grow to a sufficient size to obstruct the urethra. The clinical syndrome is confined to the male (castrate or entire) where the urethral diameter is smaller.

Clinical features

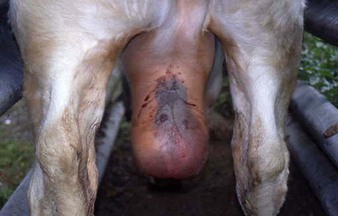

early cases are dull, anorexic, and walk stiffly. If grown sufficiently, rectal examination may reveal an enlarged and painful bladder. Diagnosis is made on the basis of changes in the preputial region. Although preputial crystals (often struvite, i.e., magnesium-ammonium-phosphate hexahydrate) appear in many calves (10.5), relatively few will develop signs of obstruction, which tends to occur in or just proximal to the sigmoid flexure, or in the distal portion of the penis. An intraoperative view (10.6) of the perineal region shows the dilated urethra proximal to the sigmoid flexure and the obstructing calculus. Continuing complete urethral obstruction results in either bladder or, more commonly, urethral rupture. The crossbred Charolais male in (10.7) has a large subcutaneous swelling containing urine as a result of urethral rupture in the sigmoid region. The swelling extends forward from the sigmoid to the preputial orifice, where dry preputial hairs are covered with crystals. A rear view (10.8) shows gross enlargement of the scrotum, especially at the neck, early bruising, and a superficial fluid ooze, all caused by accumulated urine. In occasional cases the swelling is discretely localized to the peripreputial area. In contrast, in a severe and advanced case the Friesian steer (10.9) had such severe swelling that ischemic necrosis has caused an extensive skin slough overlying the penis.

In another Hereford steer (10.10) it is the bladder rather than the urethra that has ruptured as a result of urethral obstruction. Urine has gathered in the ventral abdominal cavity, causing a progressive swelling and distension of the flanks (uroperitoneum).

Autopsy examination of a 6-year-old Shorthorn bull that died as a result of severe uremia following bladder rupture and uroperitoneum reveals a congested and hemorrhagic bladder mucosa (10.11). Numerous calculi (2–7 mm diameter) and fibrin are seen on the mucosal surface. The peritoneum tends to be diffusely inflamed, but the changes are less severe than those following septic reticuloperitonitis (4.90, 4.91). Urolithiasis frequently accompanies cases of severe pyelonephritis (10.1–10.3).

Differential diagnosis

in a mature bull this includes penile hematoma (10.23) or abscess formation, or, in a younger animal, urethral rupture due to faulty application of a bloodless castrator (Burdizzo) some days previously (see 10.36). Differentials for cases with ventral abdominal swelling not localized to the penis and prepuce include ascites (4.92), intestinal obstruction (4.88), and generalized peritonitis with massive exudation (4.91). Other differential diagnoses include cystitis (10.14), severe balanoposthitis, and severe preputial frostbite.

Management

cases of severe uremia will not pass meat inspection, so if the bladder and urethra are intact, antispasmodics may be tried for a limited period. If blockage persists, a perineal urethrotomy dorsal to the scrotum (10.6) is a salvage procedure. Urine scald and urethrostomal stricture may be subsequent problems. An alternative treatment is to make several skin incisions over the urine-filled area to facilitate drainage, and then to allow continued urine flow through the skin. Rarely, a palpable single calculus can be removed by surgery. Fattening steers with distal urethral rupture and skin slough can also be salvaged to fatten.

Amyloidosis

Clinical features

the marked presternal edema in the 3-year-old Limousin bull in 10.12 was caused by severe bilateral renal amyloidosis, which is characterized by polyuria and massive proteinuria leading to pronounced hypoproteinemia.

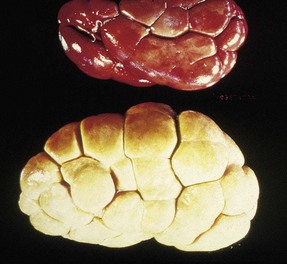

In a chronic suppurative condition the bull’s kidney in 10.13 is markedly enlarged, pale, waxy, and granular in comparison with the normal kidney above it. This degree of enlargement should be detectable on rectal palpation.

Differential diagnosis

diagnosis is difficult, especially in the presence of coexisting disease, including pyelonephritis.

Cystitis

Clinical features

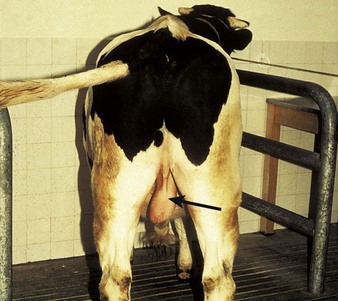

the 6-month-old heifer in 10.14 passed urine frequently and in small amounts. The perineal region had a foul odor of stale urine and shows excoriation as a result of urine dribbling. The tail is slightly elevated, indicative of urinary tenesmus. A thickened bladder wall is often detectable on rectal examination of older animals.

Male genital tract

Congenital male abnormalities

Pseudohermaphrodite (freemartin)

Definition

an individual with gonads of one sex but with contradictions in the morphological criteria of sex.

Persistent penile preputial frenulum

Clinical features

in 10.15 the penile body remains attached to the prepuce by a fine, longitudinal band of connective tissue (A). Persistent penile frenulum causing penile deviation is a congenital anomaly, but signs, such as ventral penile deviation or a failure of complete protrusion, are usually first seen at attempted intromission. In some breeds it is inherited, and surgically corrected bulls should not be used to sire replacement breeding stock. A 2-year-old Angus bull (10.16) presented for a fertility check following recent purchase, had a long-standing penile-preputial adhesion (contrast 10.15). The bull was returned to the seller. Surgical correction was considered unethical.

Testicular hypoplasia with cryptorchidism

The left testicle is descended and of normal size in the Friesian calf in 10.17. The right testicle, which is small and incompletely descended, is in the scrotal neck.

Cryptorchidism

Clinical features

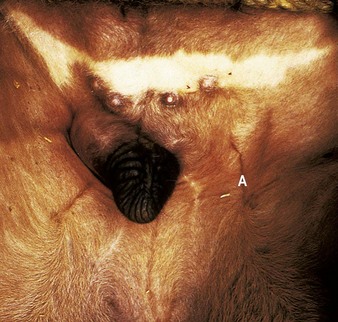

bovine cryptorchidism is a not infrequent finding in batches of calves presented for castration. All breeds are affected although there is also a possible association with the polled character. In the 4-week-old Hereford cross calf in 10.18, the normal right testicle is in the scrotal sac, but the left testicle is in an inguinal position (A). The misplaced gonad has deviated from the normal course of descent and may be termed an “ectopic testicle.” The undescended testicle is invariably considerably smaller, and when incised the seminiferous tissue is very pale in color.

Management

unless the animal is clearly identified, it is not safe to remove only the scrotal testicle because the undescended testicle may descend into the scrotum later in life, and potentially lead to unwanted pregnancies. Management options include leaving both testicles and re-examining the animal a few months later; surgically to remove the undescended testicle through the inguinal skin (which was the option chosen for 10.18); or to fatten the young bull for beef.

Penile conditions

Fibropapilloma (“wart”)

Definition

a benign tumor of epithelial and connective tissue caused by a species-specific papovavirus.

Clinical features

the 2-year-old Friesian bull in 10.19 has several highly vascular, ulcerated masses attached to the glans penis. Caudal to the large mass is a smaller, more sessile fibropapilloma. These are typical sites for such multiple, proliferating masses, which are infectious, and relatively common in groups of young bulls confined in a small area.

Management

small tumors slowly regress, and like teat warts have resolved by 2–3 years of age. Large masses may cause persistent penile protrusion and require removal (e.g., by ligation) or retention within the prepuce by a purse-string suture, which was the option chosen for 10.19. 10.20 shows the same bull 4 months later and soon afterwards he was used for service. In some cases healing is accompanied by scarring and distortion of the penile tunic, resulting in penile deviation and failure of intromission.

Spiral deviation of penis (“corkscrew penis”)

Clinical features

a spiral or corkscrew penile conformation is a normal occurrence at ejaculation in the vagina, but premature corkscrewing may be severe enough to prevent intromission. The first case (10.21), a 2-year-old Charolais, shows a 90° ventral curvature. The second case (10.22) clearly illustrates the spiraling effect, and the difficulty of intromission. In some bulls, an ulcer on the glans penis indicates abrasion from repeated perineal contact. Rarely is the condition traumatic in origin.

Differential diagnosis

persistent penile frenulum in young bulls, scarring following fibropapillomata.

Penile and parapenile hematoma (“fracture of penis”, “broken penis”)

Clinical features

a discrete swelling is seen in the Hereford bull in 10.23, which also had a secondary prolapse of the penis. He cannot serve. The extent of the ruptured CCP is evident in the autopsy specimen of an affected penis (10.24) in which the sigmoid flexure (A) is just proximal to the mass. The black wire has been inserted into the urethra.

External penile trauma

A Limousin bull running with a 400-cow dairy herd was presented with preputial bleeding post service. Rectal stimulation to give penile extrusion (10.25) showed that the distal penis had been totally severed and a portion of approximately 15–20 cm was missing. There is a secondary superficial infection of the residual stump. The bull showed no systemic signs but culling for meat was the only option.

Preputial conditions

Prolapsed prepuce (preputial eversion)

Clinical features

preputial prolapse occurs as a breed characteristic in Bos indicus, e.g., Brahman and Santa Gertrudis, and in polled breeds which are liable to have comparatively weaker preputial muscles, although horned bulls may also be affected. Injury and infection are common causes. A partial preputial prolapse of comparatively recent onset is shown in a 6-year-old Brahman from South Africa (10.26). The mucosa has a granular appearance, with areas of superficial hemorrhage. More severe cases are very prone to secondary trauma and edema.

Preputial and penile abscess

Clinical features

in the 5-year-old Hereford bull in 10.27 the penis has been manually prolapsed. The hand holds the prepuce and penis just caudal to the point of attachment of the preputial mucosa (internal lamina) to the body of the penis, shown as a transverse fold. Pus oozes from a mucosal tear incurred when the penis was extended. Deep-red erectile tissue is evident in the defect. Below the wound, the mucosa is smooth and slightly pinkish-gray due to a further abscess pocket.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree