• Cystoscopy is used to determine if the condition is unilateral or bilateral, by visualization of hematuria from one or both ureteral orifices. Ultrasonographic examination and contrast radiographic studies are also used for diagnosis. • If the urinary tract bleeding is minor then conservative treatment consisting of close observation and repeated examinations may be all that is required. • If the bleeding has resulted in anemia or there is danger of exsanguinations then unilateral nephrectomy may be considered. • Diagnosis is visually obvious in many cases with passage of feces from the vagina or urethra but in some cases contrast radiographic studies may be required. • Several foals have had surgical correction of fistulae and accompanying atresia ani. However, the decision for surgery should be based on the number of accompanying congenital defects and several surgical procedures may be required. • There is some evidence to suggest that the condition is hereditary and as such if affected animals are surgically corrected they should not be used for future breeding. • The diagnosis may be suspected on the basis of clinical signs such as urine dribbling but definitive diagnosis requires endoscopy or cystography. • This malformation can only be corrected by means of reconstructive surgery or, if the condition is unilateral, nephrectomy. Reconstructive surgery is rarely successful as it is technically difficult to perform and post-surgical complications such as renal infections are common. • Nephrectomy is also a difficult surgical procedure but the success rate is higher with this approach. • The observation of urine dribbling from the umbilical stump of a young foal is the basis for making a diagnosis of patent urachus, although sonographic imaging may be used to confirm the patent status of the structure internally and assess associated structures. • Currently many practitioners recommend treatment consisting of 5–7 days of antimicrobial support and keeping the foal’s ventral abdomen clean and dry, with twice to four-times-daily dipping of the external umbilical stump with a 1 : 4 chlorhexidine : water or dilute iodophore solution. • Topical applications of silver nitrate are no longer routinely recommended. • In cases of foals which are largely recumbent it may be useful to catheterize the bladder, thus removing the physical pressure of bladder distension which may contribute to maintaining a patent urachus. • The earliest sign is usually frequent stranguria and repeated posturing to urinate. Sick foals, especially those that are recumbent, may not show these signs and stranguria is frequently confused with tenesmus. • Affected foals show progressive abdominal distension and depression with a palpable fluid thrill may be detected across the abdominal cavity. • The foal may still continue to void urine through the urethra and as such the observation of the passage of urine does not preclude a diagnosis of ruptured bladder. • As the condition progresses these foals develop hyponatremia, hypochloremia, hyperkalemia and azotemia. Depending on the timing of presentation, the metabolic derangements that develop can result in other signs: hyponatremia can result in neurologic disturbances including convulsions; progressive hyperkalemia results in cardiac dysrhythmias. • Uroperitoneum may also be caused by disruption of the urethra, urachus or ureters (rarely). In cases of urethral leakage in colts subcutaneous accumulation of urine in the scrotal area is frequently seen. Depending on the site of injury this may occur alone or in combination with uroperitoneum. Uroperitoneum associated with urachal disruption may also be accompanied by subcutaneous leakage of urine in the umbilical area. • Progressive accumulation of fluid which may be accompanied by persistent straining will force significant amounts of urine down the inguinal canals and result in swelling of the scrotum and prepuce. • Transabdominal ultrasound is very useful in examination of foals with suspected uroperitoneum, and quickly reveals anechoic-to-hypoechoic fluid free in the peritoneal cavity, with bowel loops and other viscera floating on and in the fluid. The rent in the bladder, whether congenital or acquired, is nearly always located in the dorsal wall but is generally difficult to visualize. • A fluid sample may be obtained via abdominocentesis and assayed for creatinine concentration. If the creatinine concentration in the peritoneal fluid is twice or higher than the serum concentration, a diagnosis of uroperitoneum may be rendered. However, it is important to note that serum electrolyte and creatinine concentrations may be normal in the early stages of the disorder and should not be used as a means of ruling out the condition. • In most instances slow drainage of the abdomen is initiated. Removal of urine from the abdomen helps to prevent worsening of the metabolic condition. In cases of severe abdominal distension resulting in respiratory compromise, abdominal drainage is a must. • Uroperitoneum is a metabolic rather than a surgical emergency and surgery should be delayed to allow for correction of electrolyte abnormalities. Correction of hyperkalemia to a serum concentration <6 Eq/L is the most important consideration prior to general anesthesia. Administration of 1–3 L of 0.9% NaCl/5% glucose solution can be used to treat the hyperkalemia. • In foals for which surgery is not an option or in foals with urethral or urachal tears, placement of an indwelling urinary catheter in combination with an indwelling peritoneal drain may facilitate sufficient removal of urine to permit healing. • Placement of a urinary catheter for a couple of days post surgery to maintain an empty bladder is not usually required but should be used in foals where bladder rupture was deemed to be secondary to sepsis with necrosis of the bladder wall. Balloon-tipped Foley catheters with 10–30 ml of sterile saline solution in the balloon to keep it in a dependent position in the bladder lumen work well, but rigorous monitoring and nursing care, including the administration of broad-spectrum antimicrobials, is necessary. • In foals, the prognosis for full recovery, barring complications, is very good. • Uroperitoneum may recur after surgery in an occasional foal as a result of ongoing leakage or further necrosis. When this occurs and the volume of fluid in the abdominal cavity is small, it can be managed conservatively by the placement of an indwelling catheter for 3–5 days. A second celiotomy may be required in some cases. • The presence of free urine in the abdominal cavity (sometimes with blood-staining and inflammatory cells) may be detected by paracentesis. Cystoscopy and/or ultrasound examination of the bladder may help to identify the site of rupture and the size of the lesion which will influence the treatment. • Instillation of dye such as methylene blue into the bladder which can then be recovered from the abdomen may help to identify small defects. • Depending on the cause and extent of damage surgical repair can be attempted. Medical management would involve placement of a urinary catheter in conjunction with an abdominal drain. This is only likely to work in cases where the defect is very small. • A good history is imperative to determining if the primary problem is polydipsia or polyuria. While they occur together one is usually a physiological response to the other. Therefore a horse for example with psychogenic polydipsia will as a result have polyuria. While similarly, a horse with polyuria due to renal failure will have a physiological polydipsia as a result. • A good history should also rule in or out behavioral factors, drug administration, concurrent disease that is already being treated or clinical signs consistent with other disorders such as renal failure or Cushing’s. • In many cases it may be necessary to measure water intake and urine output over a 24-hour period. A complete blood count and serum biochemistry profile should be performed in addition to urinalysis. • Water deprivation test. If the horse shows no clinical or laboratory features of renal failure, endotoxemia, sepsis or Cushing’s disease then a water deprivation test can be performed to assess the ability of the renal tubules to respond to ADH. The horse is weighed and a urine sample obtained for determination of specific gravity (SG). The horse is then confined without access to water and urine samples collected every 2 hours. The test ends when the urine has a specific gravity (SG) of 1.025 or the horse has lost 5% of its body weight, whichever comes first. If the horse responds by producing urine with a SG >1,025 then he can be diagnosed as a psychogenic water drinker; if he fails to concentrate the urine, then a modified water deprivation test should be performed. • Modified water deprivation test. Water access is restricted to 40 ml/kg/day for up to 4 days. This will result in concentration of urine in horses with psychogenic polydipsia that have washout of renal medullary electrolytes. The horse should still be weighed daily and the test ended if the horse has lost 10% of its body weight and SG is still <1.025 as these cases may have diabetes insipidus. • Desmopressin response test. Administration of 20 µg of desmopressin acetate (DDAVP) allows differentiation between central and nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. If the urine concentrates in response to the DDAVP then the diabetes insipidus is central, if not it is nephrogenic.

Urinary tract disorders

Developmental disorders

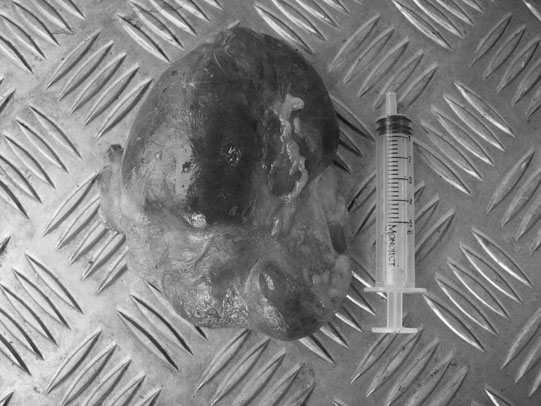

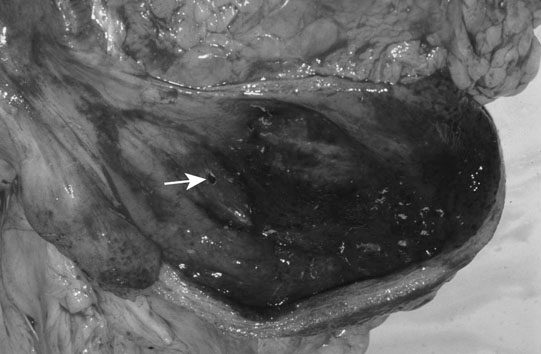

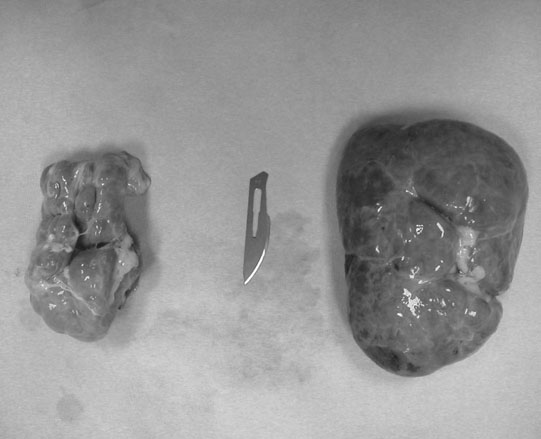

Renal agenesis, hypoplasia and dysplasia (Figs. 5.1 & 5.2)

Vascular anomalies

Diagnosis and treatment

Rectourethral and rectovaginal fistulae (Figs. 5.7 & 5.8)

Diagnosis and treatment

Ectopic ureter (Fig. 5.9)

Diagnosis and treatment

Patent urachus (Fig. 5.10)

Diagnosis and treatment

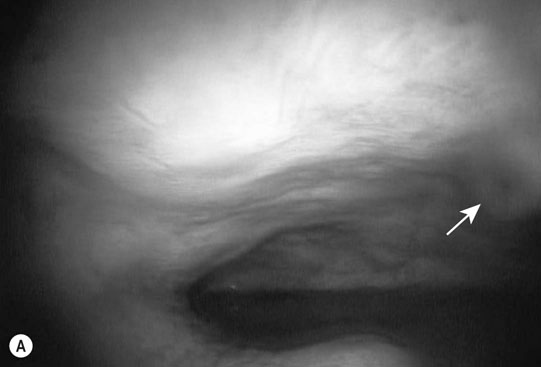

Uroperitoneum (Figs. 5.11–5.18)

Clinical signs

Diagnosis

Treatment

Prognosis

Non-infectious disorders

Bladder rupture (Fig. 5.19)

Diagnosis and treatment

Polyuria/polydipsia (Fig. 5.20)

Diabetes insipidus

Psychogenic polydipsia

Diagnosis and differentiation

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree