Chapter 16 Upper Airway Disease

CLINICAL SIGNS

Hyperthermia is a common clinical sign in dogs with upper airway disease. This occurs less frequently in feline patients, likely due to their more sedentary lifestyle. Panting is one of the primary mechanisms of thermoregulation in animals; the movement of fresh air through the upper airway effectively increases heat loss through evaporation.3,4 In animals with upper airway disease, this air movement is compromised, predisposing them to hyperthermia. This hyperthermia can be extreme, and aggressive cooling may be necessary in severely affected patients (see Chapter 167, Heatstroke).5

EMERGENCY STABILIZATION

Although treatment varies depending on the underlying disease process, the general emergency approach is similar in all patients with upper airway disease. As previously mentioned, these animals are fragile and can decompensate quickly, so any additional stress can be life threatening and will lead to an increase in oxygen requirements and therefore respiratory rate. This increased respiratory rate will only further exacerbate upper airway dysfunction. Early stabilization often relies on the administration of anxiolytics and sedatives (see Chapter 162, Sedation of the Critically Ill Patient). These agents should be given IM initially if the patient is not stable enough to undergo the stress of placing an IV catheter.

In patients with an elevated temperature, external cooling methods should be instituted. If sedation and oxygen therapy, with or without steroid therapy, fails to stabilize the patient, intubation is indicated. In the rare case in which intubation is not possible, an emergency tracheostomy should be performed to achieve a patent airway (see Chapter 18, Tracheostomy). When an emergency tracheostomy is not feasible, a small catheter may be passed into the trachea through the mouth or between tracheal rings and high-pressure jet ventilation or repetitive oxygen boluses from an anesthesia oxygen flow valve may be delivered until a tracheostomy is performed.

DIAGNOSTICS

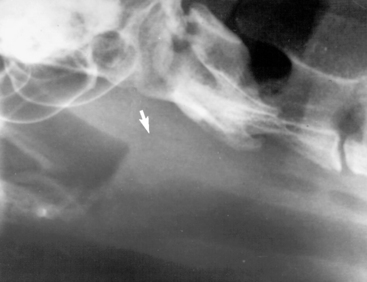

Although rarely diagnostic for a specific cause of upper airway disease, radiographs are important for evaluating both the upper and lower respiratory tracts. One ventrodorsal and two lateral views of the thorax should be taken to evaluate for metastatic disease, aspiration pneumonia, or noncardiogenic pulmonary edema. Thoracic radiographs are also used to evaluate the trachea and look for intrathoracic masses. Cervical radiographs may show evidence of laryngeal or pharyngeal neoplasia (Figure 16-1), radiodense foreign bodies, or extramural masses causing compression of the larynx or trachea. In patients with nasal or nasopharyngeal disease, skull radiographs (or computed tomography) may be indicated to evaluate the nasopharynx, the bullae, and the external canal and petrous temple bone. Unlike thoracic and cervical radiographs, patients undergoing skull radiography require general anesthesia for proper radiographic positioning.

Figure 16-1 Lateral cervical radiograph depicting a mass effect in the laryngeal region.

From Costello MF, Keith D, Hendrick M, King L: Acute upper airway obstruction due to inflammatory laryngeal disease in 5 cats, J Vet Emerg Crit Care 11:205-210, 2001.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree