CHAPTER 111 Ultrasound of the Shoulder

Ultrasound of the shoulder region in horses is often equated with evaluation of the biceps brachii tendon and bicipital bursa. This is reflected by the relatively large number of publications on biceps tendonitis and bicipital bursitis; however, injuries to other structures can be a source of shoulder lameness. Unfortunately, it is often difficult to localize shoulder lameness to a specific structure based on physical examination or radiographic findings. Nuclear scintigraphy may help localize the lameness to a particular region of the shoulder, but ultrasonography or radiography remains necessary to delineate the cause of increased radiopharmaceutical uptake. Ultrasonographic examination of all shoulder structures will increase the likelihood of an accurate diagnosis on which treatment decisions and prognosis can be based. Evaluation of most structures is relatively straightforward, and with practice a complete examination can be quickly performed. Whenever possible, radiographs should be obtained before ultrasound examination because of their complementary nature.

TECHNIQUE

Biceps Brachii Tendon

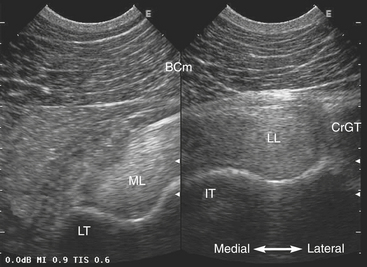

The biceps brachii tendon originates from the supraglenoid tubercle of the scapula, where the tendon has a thin, crescent shape on transverse views. The tendon enlarges as it courses between the supraglenoid tubercle and humeral tubercles and has a somewhat amorphous appearance at this location owing to varying amounts of fat. Immediately proximal to the humeral tubercles, the tendon begins to assume a partially bilobed appearance. At the humeral tubercles, lobulation becomes more evident (Figure 111-1). The lateral lobe is located within the intertubercular groove between the cranial eminence of the greater tubercle (point of the shoulder) and the intermediate tubercle. The medial lobe appears smaller than the lateral lobe and is situated within the intertubercular groove between the intermediate and lesser tubercles. Both lobes appear relatively homogeneous, although hypoechoic areas can be seen as a result of the normal curvature of the tendon over the humeral tubercles. Mild injuries to the biceps tendon can be difficult to detect for this reason, and comparison to the contralateral limb is often required.

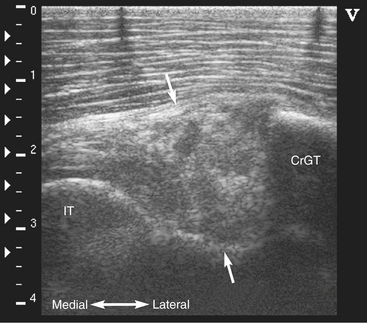

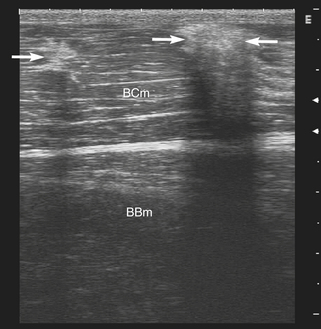

Moderate to severe injuries often create distortion in the normal shape of the lobes of the biceps tendon. The injured tendon may show discrete hypoechoic areas or become diffusely hypoechoic or heterogeneous (Figure 111-2). Injuries can occur secondary to trauma or in association with humeral tubercle fractures. Distal to the humeral tubercles, the tendon quickly transitions into muscle. Hyperechoic areas of dystrophic mineralization are commonly seen within the brachiocephalicus muscle overlying the biceps tendon. These areas can be quite large and occasionally obscure the image of the biceps tendon as a result of acoustic shadowing (Figure 111-3). They are considered an incidental finding from previous minor trauma to the shoulder region.

Bicipital Bursa

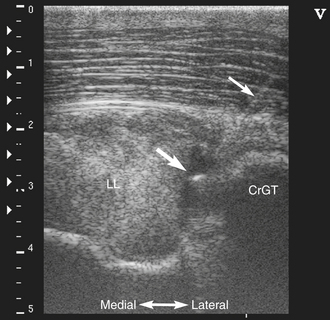

The most reliable site to image mild to moderate bursal effusion or synovitis is immediately distal to the point of the shoulder between the lateral lobe of the biceps tendon and the cranial eminence of the greater tubercle. This is also a convenient location for intrabursal needle placement (Figure 111-4). Measurement of the distance between the biceps tendon and humeral tubercles is not a reliable indicator of bursal effusion because of the pressure exerted on the tubercles by the tendon. Because effu-sion follows the path of least resistance, a substantial volume of fluid may accumulate in the distal recess of the bursa despite a normal appearance at the level of the humeral tubercles. The large extent of the bursa also increases the potential for synovial contamination by shoulder wounds or lacerations. Ultrasonographic characteristics of septic bursitis include marked thickening of synovial membranes that show a lacy or edematous appearance (Figure 111-5). Severe effusion is not a consistent feature of septic synovial structures, and the absence of effusion does not rule out sepsis. When present, fluid may be echogenic or hypoechoic. Swirling of the fluid on ballotment suggests a cellular nature. Ultrasound-guided aspiration will assist with fluid sampling for cytologic analysis, culture, and sensitivity, especially in horses with minimal fluid accumulation.